The effect of resilience on emotional intelligence and life satisfaction in mountain sports technicians

*Corresponding author: David Molero dmolero@ujaen.es

Cite this article

Martín-Talavera, L., Mediavilla-Saldaña, L., Molero, D. & Gavín-Chocano, O. (2024). The effect of resilience on emotional intelligence and life satisfaction in mountain sports technicians. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 155, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2024/1).155.01

Abstract

Mountain sports have their own characteristics, different from other outdoor sports modalities with similar characteristics. Emotional intelligence and resilience are likely to positively affect sport performance in extreme conditions. In this study, 788 athletes over 18 years of age (age of majority in Spain) from the Spanish Federation of Mountain Sports and Climbing (FEDME) participated, 593 men (75.3%), 193 women (24.5%), and 2 persons (0.3%) who considered themselves to belong to the category “other gender” (non-binary, etc.). The mean age was 49.8 years (± 12.8). The Resilience Scale (RS-14), Wong-Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS-S), and Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) were used as resources. The aim was to provide evidence on the potential for resilience between emotional intelligence and life satisfaction in mountain and climbing athletes. The results of structural equation modelling (SEM) showed high coefficients of determination for the resilience variables [(Q2 =.553); (R²=.663)] and life satisfaction [(Q2 =.301); (R²=.422)]. In the future, this research will require specific studies by sport modality for this area, with a large number of practitioners and disciplines, as well as its possible applications for the improvement of emotional factors.

Introduction

Mountain sports have experienced significant growth worldwide, especially in the last decade (Ayora-Hirsch, 2022). In Spain, the recent Estudio de Hábitos Deportivos de España 2022 (“Study on Sports Habits in Spain 2022”, Ministry of Culture and Sports, 2022) reports that the sport discipline most practised by the Spanish population in 2021 was hiking-mountaineering, with 30.8% of the Spanish population practising it. Mountain sports have their own characteristics, different from other outdoor sports modalities with similar features, particularly the risk conditions in some cases, which can condition the profile of the athletes at a physical level, but, above all, at a psychological level (Gavín-Chocano et al., 2023). This study analyses the resilience, emotional intelligence, and life satisfaction of people linked to the Spanish Federation of Mountain and Climbing Sports (FEDME), the only Spanish sports federation that will participate in the Summer Olympics with climbing and in the Winter Olympics with ski mountaineering, which will debut as an Olympic discipline in Milan-Cortina d’Ampezzo 2026.

We consider it necessary to carry out this study because of its practical usefulness, both for the people who practise these sports and for those who are responsible for their management. The evidence obtained will be useful for decision-making in its management tasks, given its practical and social application (transfer), in addition to the knowledge that can be generated, based on the theoretical and scientific contributions that will be made.

There are still few studies that analyse emotional intelligence (EI), resilience, and its relationship with life satisfaction in mountain sports, due to the characteristics of the discipline. EI and resilience not only refer to the adaptive capacity that can be developed in the face of an adverse experience, but can also positively affect sport performance in extreme conditions. Resilience is defined as the ability to exhibit adaptive responses to adverse situations (Salmela-Aro et al., 2019). It is a factor related to emotions, which generates determination, self-control, self-efficacy, optimism, well-being, and the ability to solve problems in a positive way (Salanova, 2021). In this regard, Tabibnia (2020) considers that common techniques to increase resilience include exposure to nature by hiking in the mountains. Resilience of mountain athletes has been analysed in connection with behavioural addiction to extreme mountain sports (Méndez-Alonso et al., 2021; Niedermeier et al., 2022), and with the management of emotional regulation (Brooks & Goldstein, 2015) for better risk management (Habelt et al., 2022). In this sense, resilience in mountain and outdoor athletes should combine psychological aspects and emotional management processes (Jaramillo-Moreno & Rueda, 2021).

The conceptualisation of the EI construct is an issue that requires consensus among researchers. Petrides et al. (2004) distinguish 2 different constructs of EI: on the one hand, EI as a personality trait, and on the other, EI as an ability. EI as an ability should be measured through performance tests, while EI as a trait would refer to self-perceptions concerning one’s ability to recognise, process, and use emotionally charged information. Among the studies of practitioners of outdoor sports activities, we highlight those that analyse the use of emotional regulation strategies by athletes (Castro-Sánchez et al., 2019; Nicolas et al., 2019), or the influence of EI on climbing performance (Garrido-Palomino & España-Romero, 2019; Laborde et al., 2015).

One of the most fruitful areas of EI research focuses primarily on providing evidence of the relationship with psychological well-being and life satisfaction, referring to the state of the individual in which both objective and subjective needs are satisfied (Biswas-Diener, 2022). In subjective well-being, people’s emotional experiences, the satisfaction of different life domains, and the overall assessment of life are studied. Próchniak (2022) analysed the relationship between life satisfaction and optimism in mountain sports, personality, and emotional responses. It has been shown that the most life-satisfied resilient athletes are those in whom high EI values can be predicted (Baumsteiger et al., 2022).

The positive effects of EI and resilience, related to life satisfaction, can promote effective coping strategies in adverse situations (Cejudo et al., 2016).

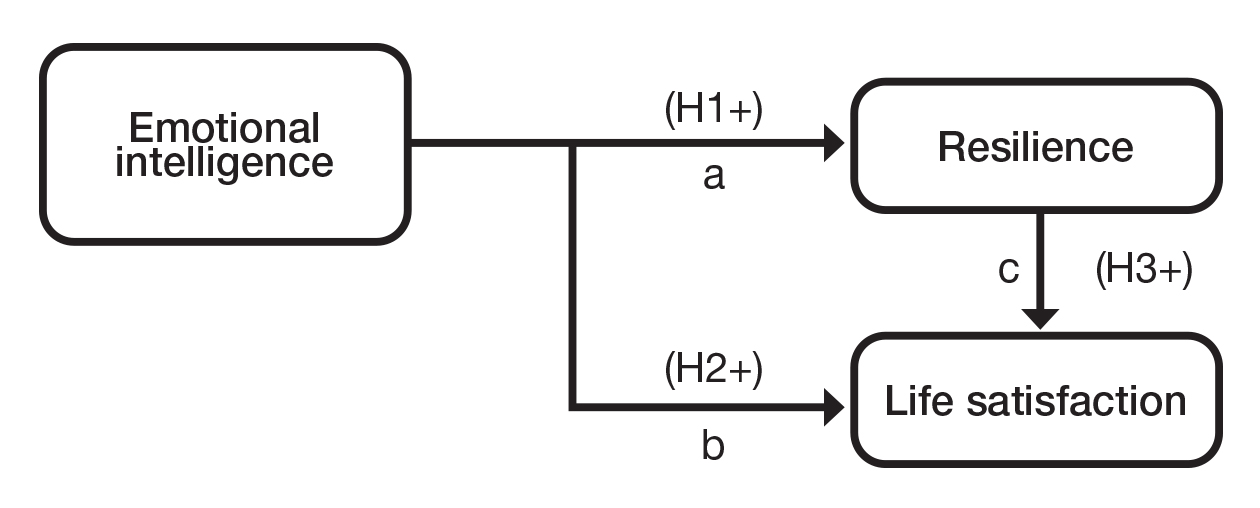

The aimof this study is to provide evidence on the potential effect of resilience on EI and life satisfaction in mountain and climbing athletes in Spain. The following are considered as working hypotheses (see Figure 1): (H1) EI will be positively related to resilience; (H2) EI will be positively related to resilience; (H3) Resilience as EI potential will be related to life satisfaction.

Method

Participants

A total of 788 people with a sports qualification participated in this study through the use of a non-probabilistic sampling of incidental or casual type. The participants had a sports licence with FEDME in the year 2022 and had taken some formal or federative training in mountain sports or climbing. Regarding gender distribution, 75.3% were men (593 cases), 24.5% were women (193 cases) and 2 persons (0.3%) considered that they belonged to the category “other gender” (non-binary, etc.). The mean age of the participants was 49.8 years (± 12.8), ranging from 18 to 78 years. The sample exceeded the minimum number of participants required when making an inference of sample size for a confidence level of 95% and an estimation error of 4% (estimated number of participants: 598).

Resources

It was considered necessary to use three data collection instruments to obtain evidence of the variables contemplated in the study (EI, resilience, and life satisfaction).

Wong-Law’s Emotional Intelligence Scale –WLEIS-S, in its Spanish version (Extremera et al., 2019), consists of 16 items and 4 dimensions: intrapersonal perception (self emotional appraisal, or SEA), interpersonal perception (others’ emotional appraisal, or OEA), assimilation (use of emotions, or UoE) and regulation of emotion (RoE). A 7-point Likert-type scale (1 to 7 points) was used. In our study (see Table 1) the reliability (Cronbach’s α coefficient) for each dimension is .90, .90, .89 and .89, respectively; and .90 for all four factors for the McDonald’s ω coefficient.

14-item Resilience Scale (RS-14), Spanish version by Sánchez-Teruel and Robles-Bello (2015), with 14 items that respond to a Likert-type rating (1 to 7 points), which are divided into two factors: Personal Competence (11 items), and Acceptance of Oneself and Life (3 items). The reliability of scores on both dimensions of this scale: Personal Competence α = .89 and ω coefficient = .90; and, for Acceptance of Oneself and Life, Cronbach’s α = .88 and ω = .90.

Satisfaction With Life Scale.The SWLS was used to assess life satisfaction,in our case, the version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale of Vázquez et al. (2013), consisting of five items (1 to 7 points) where participants must indicate the degree of agreement or disagreement for each of the resource’s response options. In our study, the reliability was α = .86 and .88 for the ω coefficient.

Procedure

The ethical guidelines promoted and encouraged by national and international regulations for conducting research with people were followed, through the completion of informed consent and the guarantee of confidentiality and anonymity of the data obtained. Participation in the study was voluntary in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (WMA, 2013). The resource was administered individually via the Google® platform (Google LLC). The sample participants received an email with the link to the forms for their response. The approximate response time for each participant was 15 minutes, and the information was collected during the months of May to June 2022. This research has been approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Jaén (Spain), with identification code OCT.22/2-LINE. Participants who requested to receive information on the results of the study will receive this article in electronic format when it is published.

Data analysis

First, it was determined whether the data assumed normality and it was found to follow a normal distribution. The assumptions of multicollinearity, homogeneity, and homoscedasticity were tested. Descriptive statistics were obtained, and validity and reliability (alpha and omega coefficients) were analysed a priori using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The analyses were carried out using the program SPPS AMOS 25, Jamovi software version 1.2 and SmartPLS (version 3.3.6). For the coefficients considered in this study, the Chi-square test (χ2), the degrees of freedom (gl), and the comparative fit indices (CFI), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), standardised root mean squared residual (SRMR) and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) were used. A confidence level of 95% was used in all cases. The statistical power obtained is .948 for the predictors of life satisfaction used. A Bootstrapping procedure with 2,000 subsamples was used to calculate the structural equation model of the variables considered, reporting the predictive significance and the standardised regression coefficient (Q2 and R²).

Results

From the data obtained with each of the instruments, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was carried out to verify the validity and internal structure of each item. Critical Z score values (95% confidence level) determined a reduced p value that reflected statistically significant spatial structure in the data.

The factor loadings (see Table 1) for the items of the EI scale (WLEIS-S), presented an adequate fit (Hair et al., 2021), χ2/df = 3.259, with CFI = 0.973, SRMR = .0380, RMSEA = .067.

The overall reliability of the WLEIS-S scale was α = .906 and ω = .909 (see Table 4).

The factor loadings (see Table 1) for the items of the EI scale (WLEIS-S) presented an adequate fit (Hair et al., 2021), χ2/df = 2.967, with CFI = 0.911, SRMR = .046, RMSEA = .078. The reliability of this scale was Cronbach’s α = .899 and McDonald’s ω = .906 (see Table 2 and Table 4).

For the factor loadings (see Table 3) of the life satisfaction scale (SWLS) items, an adequate fit was also obtained, χ2/df = 3.041; with CFI = .963; SRMR = .034; RMSEA = .068. The overall reliability of this scale was Cronbach’s α = .885 and McDonald’s ω = .907 (see Table 4).

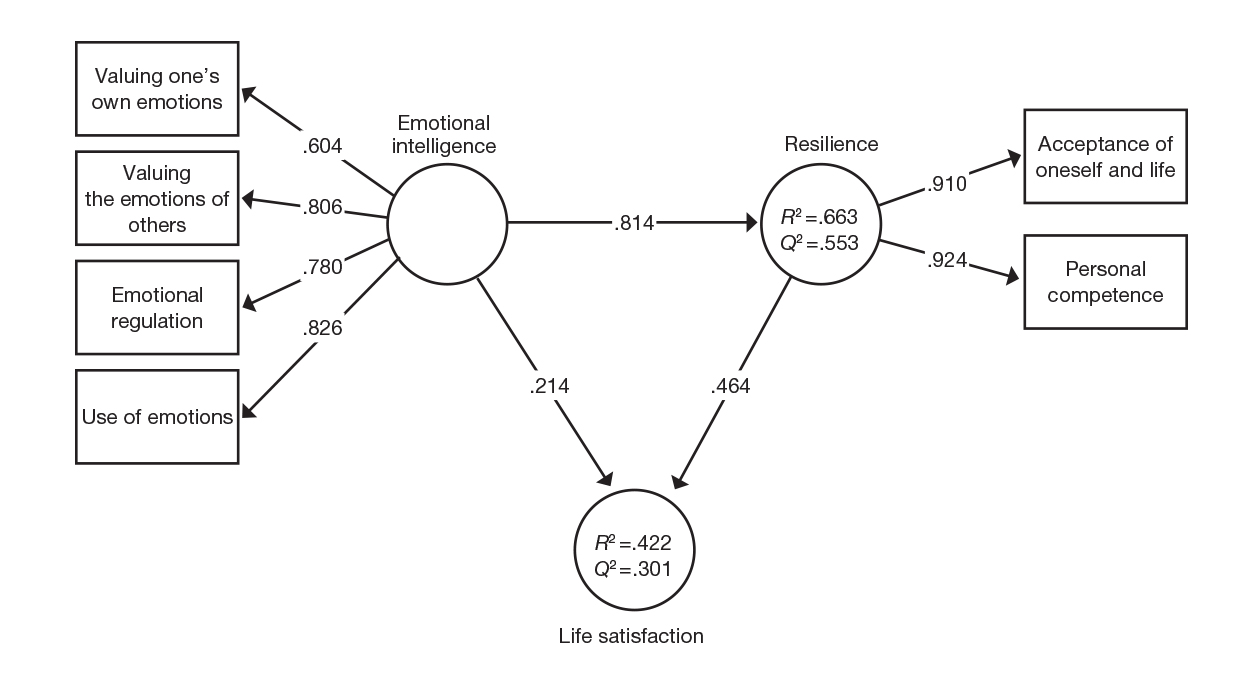

Structural model

To assess the robustness of the factor loadings and the significance between variables, the Bootstrapping procedure was used with 2,000 subsamples (Hair et al., 2021), resulting in the structural model (Figure 2) where the variables considered in this study are reported. Predictive relevance is obtained in the analysis in the estimation of the measurement model, with a good fit of the standardised regression coefficient model for resilience [(Q2 = .553); (R² = .663)] and life satisfaction [(Q2 = .301); (R² = .422)]. In this sense, R² values above .66 indicate a substantial fit of the model and above .33 a moderate fit following Chin’s (1998) indications, and in our case it would be substantial for resilience and moderate for life satisfaction.

Table 4 presents the reliability (through alpha and omega coefficients), external loadings, and composite reliability index (CRI) scores obtained. The convergent validity or degree of certainty that the proposed indicators measure the same latent variable or factor, through the estimation of the average variance extracted (AVE), values must be greater than .5, according to the criteria of Becker et al. (2018).

A high value of AVE will have a better representation of the loading of the observable variable. All values obtained are above .5, fulfilling the established criteria.

The discriminant validity (Table 5) was examined through the analysis of the cross-loadings of each of the latent variables and their respective observed variables, with the loadings being higher than the rest of the variables.

Table 6 shows the results of the hypothesis testing following the criteria of Hair et al. (2021), where the causal relationship with the latent variables can be observed. The data of the t test (values above 1.96) indicate the consistency of the model. The results that showed a higher value were: emotional intelligence → resilience (β = .814, t = 19.979, p < .001); emotional intelligence → life satisfaction (β = .214, t = 3.898, p < .001); and resilience → life satisfaction (β = .464, t = 8.254, p < .001).

Discussion and conclusion

According to the first hypothesis (H1), we have obtained evidence confirming that EI is related to resilience. Resilience is a factor that directly affects the emotional area, providing organisation, determination, self-control, and the ability to solve problems in a positive way.

Our results coincide with those of studies that consider that resilience in mountain athletes as a psychosocial process should combine psychological and social aspects as processes of emotional management and use in high-level sports disciplines (Jaramillo-Moreno & Rueda, 2021). One of the keys to the relationship between EI and resilience lies in the fact that stressful events are highly emotionally charged. People’s ability to regulate emotions is a key factor in their acceptance of oneself and life. Along these lines, the relationship between EI and resilience indicates the presence of increased well-being to cope with experiences of adversity and to develop personal competence (Brooks & Goldstein, 2015).

With regard to the second hypothesis (H2), we obtain a relationship between EI and life satisfaction, which confirms it. This is in line with Cejudo et al. (2016), finding positive effects of EI and adaptive responses or resilience, related to life satisfaction, favouring effective coping strategies in the face of adverse situations.

With regard to the third hypothesis (H3), it becomes evident that resilience acts as a variable that enhances EI and life satisfaction. Research corroborates these results, which show that resilient athletes who are more satisfied with life are significantly and positively predictive of higher EI (Baumsteiger et al., 2022). Relating these aspects, there are several elements that connect resilience to life satisfaction, such as: health, sport performance, context, as well as emotions experienced in personal activities and relationships (Castro et al., 2019; Molero et al., 2012; Nicolas et al., 2019). In this approach, athletes who exhibit higher personal competences also show higher life satisfaction, and resilience plays a mediating role with EI (Baumsteiger et al., 2022).

Sánchez-Álvarez et al. (2016) highlight that the appropriate use of certain emotional strategies could contribute to experiencing a higher rate of positive emotional states and the reduction of negative emotional states, thus having a positive impact on people’s well-being and health. Frochot et al. (2017) analysed the satisfaction of the practitioners of these mountain sports disciplines and the self-perceived well-being that this activity produced in mountain tourism contexts, obtaining results along the same lines as those presented in our work. For Schebella et al. (2019), outdoor sporting activity in a natural environment improves self-esteem and is more restorative than in an urban environment. In this regard, the work of Engemann et al. (2019) found that the risk of psychological disorders from adolescence to adulthood decreases with an increase in the amount of green space near the place of residence.

If we globally approach the discussion of the results obtained and their relationship with the hypotheses considered, the positive effects of EI on resilience and its relationship with life satisfaction, which have been studied in other contexts, have been evidenced, obtaining similar results. It has been shown that people with high EI scores are more satisfied with life (Gavín-Chocano & Molero, 2020), and that there is a positive influence of EI on life satisfaction, both being related to resilience (Mérida-López et al., 2019). In line with this, Quirante-Mañas et al. (2023) consider that satisfaction is also an emotional reaction, realised as a cognitive judgement following the choice of a sporting event, something that may provide incentives to engage in these activities. Finally, we would like to highlight that EI is a factor of psychological adjustment associated with well-being and a key variable in personal and social growth (Baumsteiger et al., 2022), key in the adaptive process and in social and emotional learning throughout our lives (Brackett et al., 2019).

Before concluding our proposal, it is necessary to reflect on the possible limitations of our study. These will be taken into account for future work that may have a longitudinal measurement character beyond the cross-sectional character of the present proposal. It will also be useful to analyse the variables considered in other contexts and in other sport disciplines. One of these constraints, which will have to become a future line of action, is related to participants. Our study includes people with a background of regulative and federative training, as long as they meet the condition of having a valid federative licence. Those who are not linked to the federation were not able to participate in the study and it would be advisable to include this profile in future studies. Another limitation is the lack of differentiated results by sport disciplines of mountaineering and climbing, so caution should be exercised in generalising results. In future work it will be interesting to analyse, in detail, the existence of significant differences according to gender and context in each of the disciplines.

Despite these limitations, this research makes a necessary contribution to the field of EI, resilience, and its influence on life satisfaction. On the other hand, the practical consequences of this work underline the need to strengthen emotional and resilience strategies in highly demanding athletes in order to improve personal well-being.

Acknowledgements

The research has been made possible thanks to the collaboration provided by the Spanish Federation of Mountain Sports and Climbing (FEDME).

Declaration of Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Clearance

This study is approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Jaén, Spain (Code: OCT.22/2-LINE).

Informed consent

All participants gave their consent to participate voluntarily in the research.

References

[1] Ayora-Hirsch, A. (2022). Cien años de una pasión. In J., Perea, P. Nicolás, P., & A. Turmo (Eds.), Un siglo de montañismo federado 1922-2022 (pp. 12-19). FEDME.

[2] Baumsteiger, R., Hoffmann, J.D., Castillo-Gualda, R., & Brackett, M. A. (2022). Enhancing school climate through social and emotional learning: effects of RULER in Mexican secondary schools. Learning Environments Research, 25, 465-483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-021-09374-x

[3] Becker, J. M., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2018). Estimating moderating effects in PLS-SEM and PLSc-SEM: Interaction term generation data treatment. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling 2(2), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.47263/JASEM.2(2)01

[4] Biswas-Diener, R. (2022). Wellbeing research needs more cultural approaches. International Journal of Wellbeing, 12(4), 20-26. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v12i4.1965

[5] Brackett, M. A., Bailey, C. S., Hofmann, J. D., & Simmons, D. N. (2019). RULER: A theory-driven, systemic approach to social, emotional, and academic learning. Educational Psychologist, 54, 144-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2019.1614447

[6] Brooks, R., & Goldstein, S. (2015). The power of mindsets: Guideposts for a resilience-based treatment approach. In D. A. Crenshaw, R. Brooks, & S. Goldstein (Eds.), Play therapy interventions to enhance resilience (pp. 3-31). The Guilford Press.

[7] Castro-Sánchez, M., Lara-Sánchez, A. J., Zurita-Ortega, F., & Chacón-Cuberos, R. (2019). Motivation, Anxiety, and Emotional Intelligence Are Associated with the Practice of Contact and Non-Contact Sports: An Explanatory Model. Sustainability, 11(16), 4256. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su11164256

[8] Cejudo, J., López, M. L., & Rubio, M. J. (2016). Emotional intelligence and resilience: Its influence and satisfaction in life with university students. Anuario de Psicología, 46, 51-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anpsic.2016.07.001

[9] Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research(pp. 295-336). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

[10] Engemann, K., Pedersen, C. B., Arge, L., Tsirogiannis, C., Mortensen, P. B., & Svenning, J. (2019). Residential green space in childhood is associated with lower risk of psychiatric disorders from adolescence into adulthood. PNAS, 116(11), 5188-5193. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1807504116

[11] Extremera, N., Rey, L., & Sánchez-Álvarez, N. (2019). Validation of the Spanish version of the Wong Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS-S). Psicothema, 31(1), 94-100. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2018.147

[12] Frochot, I., Elliot, S., & Kreziak, D. (2017). Digging deep into the experience - flow and immersion patterns in a mountain holiday. International Journal of Culture Tourism and Hospitality Research, 11(1), 81-91. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijcthr-09-2015-0115

[13] Garrido-Palomino, I., & España-Romero, V. (2019). Role of emotional intelligence on rock climbing performance. Revista Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte, 15(57), 284-294. https://doi.org/10.5232/RICYDE2019.05706

[14] Gavín-Chocano, Ó., & Molero, D. (2020). Valor predictivo de la Inteligencia Emocional Percibida y Calidad de Vida sobre la Satisfacción Vital en personas con Discapacidad Intelectual. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 38(1), 131-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/rie.331991

[15] Gavín-Chocano, Ó., Martín-Talavera, L., Sanz-Junoy, G., & Molero, D. (2023). Emotional Intelligence and Resilience: Predictors of Life Satisfaction among Mountain Trainers. Sustainability, 15(6), 4991. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064991

[16] Habelt, L., Kemmler, G., Defrancesco, M., Spanier, B., Henningsen, P., Halle, M., Sperner-Unterweger, B., & Hüfner, K. (2022). Why do we climb mountains? An exploration of features of behavioural addiction in mountaineering and the association with stress-related psychiatric disorders. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-022-01476-8

[17] Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C.M., Gudergan, S. P., Castillo-Apraiz, J., Cepeda-Carrión, G.A., & J. L. Roldán. (2021). Manual Avanzado de Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Omnia Science.

[18] Jaramillo-Moreno, R. A., & Rueda, C. J. C. (2021). De la resistencia a la transformación: una revisión de la resiliencia en el deporte. Diversitas, 17(2). https://doi.org/10.15332/22563067.7085

[19] Laborde, S., Dosseville, F., & Allen, M. S. (2015). Emotional intelligence in sport and exercise: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 26(8), 862-874. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12510

[20] Méndez-Alonso, D., Prieto-Saborit, J. A., Bahamonde, J. R., & Jiménez-Arberás, E. (2021). Influence of Psychological Factors on the Success of the Ultra-Trail Runner. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2704. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052704

[21] Mérida-López, S., Bakker, A. B., & Extremera, N. (2019). How does emotional intelligence help teachers to stay engaged? Cross-validation of a moderated mediation model. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.048.

[22] Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte (2022). Encuesta de Hábitos Deportivos 2022. Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Gobierno de España.

[23] Molero, D., Belchi-Reyes, M., & Torres-Luque, G. (2012). Socioemotional competences in mountain Sports. Journal of Sport and Health Research, 4(2),199-208. http://www.journalshr.com/papers/Vol%204_N%202/V04_2_9.pdf

[24] Nicolas, M., Martinent, G., Millet, G., Bagneux, V., & Gaudino, M. (2019). Time courses of emotions experienced after a mountain ultra-marathon: Does emotional intelligence matter? Journal of Sports Sciences, 37(16), 1831-1839. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2019.1597827

[25] Niedermeier, M., Frühauf, A., & Kopp, M. (2022). Intention to Engage in Mountain Sport During the Summer Season in Climate Change Affected Environments. Frontiers, Public Health, 10, 828405. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.828405

[26] Petrides, K. V., Frederickson, N., & Furnham, A. (2004). The Role of Trait Emotional Intelligence in Academic Performance and Deviant Behavior at School. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 277-293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00084-9

[27] Próchniak, P. (2022). Profiles of Wellbeing in Soft and Hard Mountain Hikers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7429. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127429

[28] Quirante-Mañas, M., Fernández-Martínez, A., Nuviala, A., & Cabello-Manrique, D. (2023). Event Quality: The Intention to Take Part in a Popular Race Again. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 151, 70-78. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2023/1).151.07

[29] Salanova, M. (2021). Resiliencia. ¿Cómo me levanto después de caer? Editorial Prisa.

[30] Salmela-Aro, K., Hietajärvi, L., & Lonka, K. (2019). Work Burnout and Engagement Profiles Among Teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2254. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02254

[31] Sánchez-Álvarez, N., Extremera, N., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2016). The relation between emotional intelligence and subjective well-being: A meta-analytic investigation. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(3), 276-285. http://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1058968

[32] Sánchez-Teruel, D., & Robles-Bello, M. A. (2015). Escala de resiliencia 14 ítems (RS-14): propiedades psicométricas de la versión en español. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación-e Avaliação Psicológica, 2(40), 103-113. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4596/459645432011.pdf

[33] Schebella, M. F., Weber, E., Schultz, L., & Weinstein, P. (2019). The wellbeing benefits associated with perceived and measured biodiversity in Australian urban green spaces. Sustainability, 11(3), 802. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030802

[34] Tabibnia G. (2020). An affective neuroscience model of boosting resilience in adults. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 115, 321-350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.05.005

[35] Vázquez, C., Duque, A., & Hervás, G. (2013). Satisfaction with Life Scale in a Representative Sample of Spanish Adults: Validation and Normative Data. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 16(82), 1-15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24230945

[36] WMA (2013 October). Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research on Human Beings. 64th General Assembly, Fortaleza (Brazil). Retrieved from https://www.wma.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/DoH-Oct2013-JAMA.pdf

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: February 13, 2023

Accepted: 30 June, 2023

Published: January 1, 2024

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en