Influence of (Dis)empowering Climates on the Teaching Identity of Physical Education Pre-service Teachers

*Corresponding author: Ginés David López-García glopez@um.es

Cite this article

Granero-Gallegos, A., Carrasco-Poyatos, M., Rubio-Valdivia, J.M. & López-García, G.D., (2026). Influence of (Dis)empowering Climates on the Teaching Identity of Physical Education Pre-service Teachers. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 163, 38-46. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2026/1).163.04

Abstract

The aim of this study was to analyze the mediating role of academic engagement and intention to become a teacher in the relationship between (dis)empowering climates and professional teaching identity in Physical Education pre-service teachers. An observational, cross-sectional design was used. A total of 478 university students enrolled in initial Physical Education teacher education programs (44.8% women; Mage = 27.09; SD = 6.32) participated. Validated scales were used to assess empowering and disempowering motivational climates, academic engagement, intention to become a teacher, and professional teaching identity, and a structural equation model with latent variables was estimated. The results of the model highlight the importance of an empowering motivational climate for the teaching identity of pre-service Physical Education teachers, as well as the mediating role of academic engagement and intention to become a teacher, whereas a disempowering climate does not predict teaching identity. Therefore, this study underlines the relevance, for both teacher educators and researchers, of fostering empowering climates that promote academic engagement and strengthen intention to become a teacher as key drivers of teaching identity in Physical Education pre-service teachers.

Introduction

There is growing concern in teacher education about examining, analyzing, and optimizing the processes involved in building professional identity in order to prevent teachers from leaving the profession (OECD, 2020). More than 30 years of research on teaching have raised new research questions and methodological approaches to better understand how professional identity develops. In teacher education in general, and in Physical Education (PE) in particular, the different approaches that have been used have addressed the development of professional identity from a psychogenetic perspective based on the study of students’ internal characteristics (Rubio-Valdivia et al., 2024; Granero-Gallegos et al., 2025). In line with the existing evidence, not only personal influences shape the construction of a teaching identity; socially situated influences, such as the classroom climate, have also been theoretically described as key factors in this process (Day, 2011). Therefore, and since these relationships have not been empirically tested from a quantitative standpoint, the present study seeks to understand the role of classroom motivational climates through cognitive elements in the development of teaching identity in PE pre-service teachers.

(Dis)empowering Climates

Although the classroom motivational climate has been identified as the cornerstone of all educational outcomes because it is intrinsically linked to the quality of the teaching–learning process (OECD, 2020), recent educational trends have highlighted the need to combine elements drawn from Achievement Goal Theory (AGT; Ames, 1992) and Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2017). To examine in greater depth the influence of the social environment in the classroom, Duda and Appleton (2016) outlined a hierarchical, integrative, and multidimensional conceptualization that incorporates the main dimensions of the social environment within AGT (task- and ego-involving climates) and SDT (autonomy support, control, and social support). According to Granero-Gallegos et al. (2023), and following Duda and Appleton’s (2016) conceptualization, a teacher educator creates an empowering climate when they provide pre-service teachers with opportunities for choice (autonomy support); establish interpersonal criteria for success based on skill development, effort, and cooperation (task-involving climate); and make them feel valued and cared for as individuals (social support). In contrast, a teacher educator creates a disempowering climate when they establish interpersonal relationships based on rivalry and competitiveness (ego-involving climate) and use controlling and pressuring strategies so that students feel, think, and act in a particular way (controlling style). Drawing on Duda and Appleton’s (2016) multidimensional conceptualization and previous studies (Simon et al., 2025; Milton, Appleton et al., 2025), an empowering climate is expected to foster cognitive elements that are intrinsic to the education process, such as academic engagement, which can stimulate intentionality toward teaching behavior (e.g., intention to become a teacher) and, consequently, promote the development of teaching identity (Milton et al., 2025; Granero-Gallegos et al., 2025; López-García et al., 2022). Conversely, a disempowering climate is likely to undermine the cognitive processes developed by pre-service teachers, such as intention to become a teacher or academic engagement, thereby hindering the construction of a strong teaching identity (Milton et al., 2025; Granero-Gallegos et al., 2024; López-García et al., 2023).

Academic Engagement

Academic engagement has been conceptualized as a positive affective and mental state related to academic work that involves students’ intention, interest, and effort invested in the learning process (Schaufeli et al., 2006). The conceptual framework proposed by Schaufeli et al. (2006) operationalized academic engagement through three dimensions: i) vigor (perception of high levels of energy in learning), ii) dedication (perceived involvement in academic tasks), and iii) absorption (perception of high levels of immersion that are expressed in any academic task). Specifically, research in teacher education has shown the role of academic engagement as an outcome of classroom climates (López-García et al., 2022), as well as an antecedent of future behaviors (intention to become a teacher) (López-García et al., 2023). However, although academic engagement has been widely used in teacher education and its influence on the development of professional identity has been examined (Pittaway & Moss, 2013), to the best of our knowledge no study has evaluated its potential positive influence on teaching identity despite its relevance in teacher education programs.

Intention to Become a Teacher

Intention to become a teacher refers to the degree of planning and effort that pre-service teachers invest in working as teachers in the future (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). Following the theoretical framework of the Theory of Planned Behavior, Fishbein and Ajzen (2010) proposed that behavioral intention is an immediate antecedent of the degree of effort that a person is willing to invest in a given action. In this sense, intention to become a teacher is influenced by i) behavioral beliefs regarding positive or negative evaluations of teaching; ii) normative beliefs that give rise to perceived social pressure to perform certain behaviors; and iii) perceived behavioral control beliefs associated with a future behavior. Evidence in teacher education has examined the role of intention to become a teacher both as an antecedent of classroom climates (Granero-Gallegos et al., 2024) and as a precursor of key cognitive elements in the education process (López-García et al., 2023). Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge no studies have examined the role of intention to become a teacher as a precursor of behavioral intention capable of developing professional identity in PE pre-service teachers. This represents a gap in the scientific literature and an important contribution of the present study.

Professional Teaching Identity

Teaching identity has been conceptualized as a theoretical construct that allows us to position ourselves as teachers in relation to others and that encompasses different activities as well as processes of categorization and identification (Gray & Morton, 2018). In this sense, a well-established professional identity fosters commitment to the teaching profession, supports ongoing professional development, facilitates the integration of innovative educational practices, and enables teachers to adapt to adverse situations (Beijaard et al., 2009). Consequently, authors such as Gray and Morton (2018) describe the construction of professional identity as a continuous process of accepting and building one’s role, characterized by ongoing negotiation between external influences and the person (Reeves, 2018). Teaching identity is therefore not a static construct, but a fluctuating one that depends on various factors (e.g., psychological, social, personal) and is influenced by different perceptions of these factors (Day, 2011). For this reason, during teacher education, identity needs to be understood as a dynamic construct that continuously evolves through the interaction of internal (personal) characteristics and external (contextual) influences. Few studies, such as that by Rubio-Valdivia et al. (2024), have sought to understand the interaction of internal traits, and only Wong and Liu (2024) have examined the construction of teaching identity from the perspective of SDT. Thus, adding evidence on how teaching identity is constructed from the viewpoint of PE pre-service teachers represents an important contribution, as this study will provide insights into how the classroom climate created by the teacher educator influences the development of pre-service teachers’ professional identity.

The Present Study

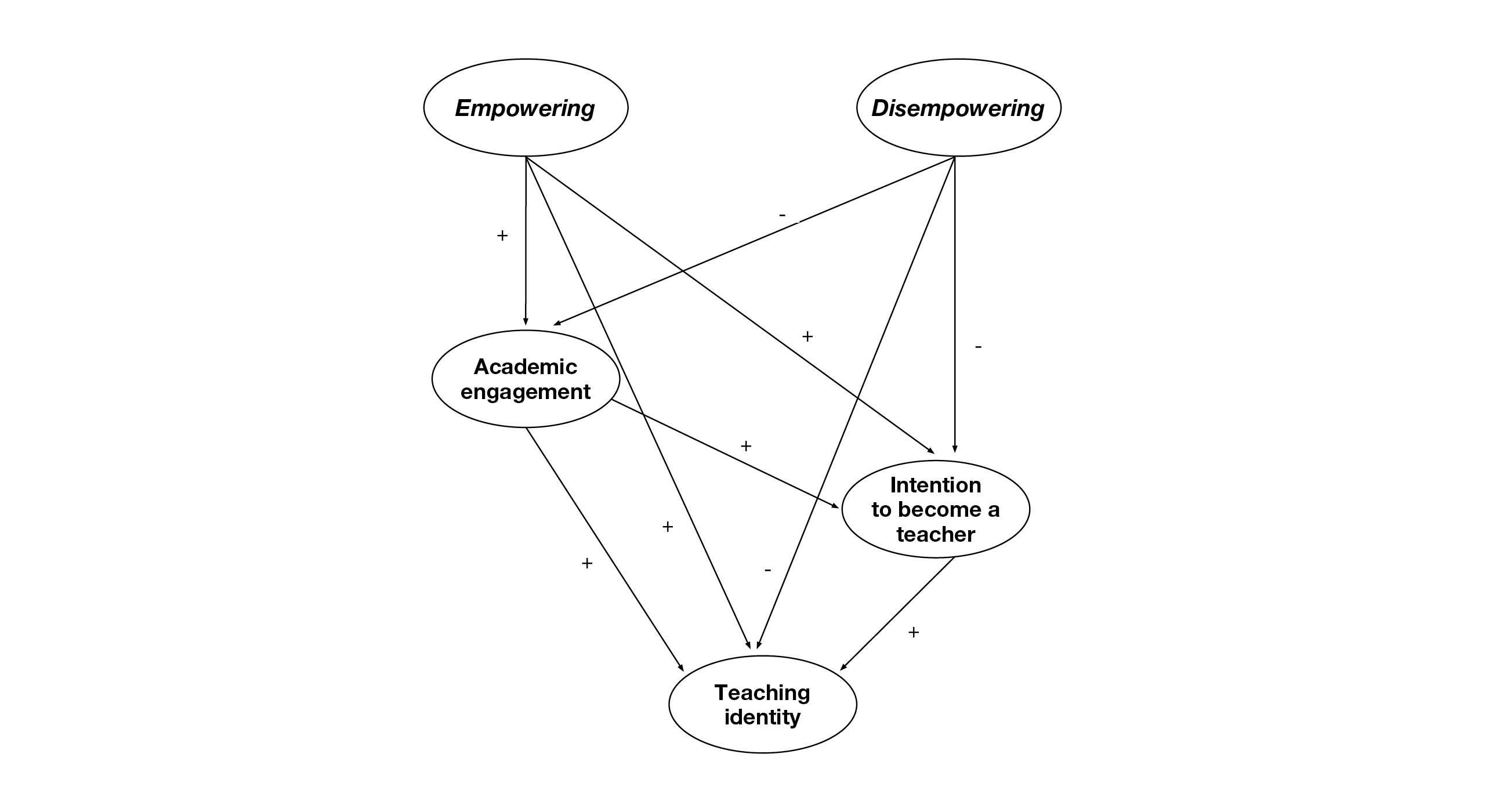

Given the importance of identity both during teacher education and throughout teachers’ professional careers, analyzing the social factors that can foster professional teaching identity is highly relevant for its study. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have considered Duda and Appleton’s (2016) multidimensional conceptualization when examining the influence of (dis)empowering climates on professional teaching identity. The aim of this study was therefore to analyze the mediating role of academic engagement and intention to become a teacher in the relationship between (dis)empowering climates and teaching identity in pre-service teachers. Drawing on the postulates of SDT and AGT and on previous studies, a hypothesized model was developed (see Figure 1) to examine these relationships. The description of the present study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) initiative (von Elm et al., 2008; Sánchez-Martín et al., 2024a).

Method

Design

This study used an observational, cross-sectional design. Participants were students enrolled in the Master’s Degree in Secondary Education Teaching (MAES) at eight public universities in Andalusia (Spain). The inclusion criteria were: i) regular, face-to-face attendance at classes; and ii) being enrolled in the MAES in the PE specialization during the 2021/2022 academic year. The exclusion criteria were: i) not completing the questionnaire in full; and ii) not providing informed consent for data processing.

Instruments

Teacher educator-created (dis)empowering climate

The Educator-Created Empowering and Disempowering Climate Questionnaire (ECEDMCQ; Granero-Gallegos et al., 2024) was used. The ECEDMCQ consists of 21 items grouped into five factors: autonomy support (five items; e.g., “My teacher offered different opportunities and options”), social support (three items; e.g., “My teacher listened openly and did not judge personal feelings”), task-involving climate (four items; e.g., “The teacher expects us to learn new skills and acquire new knowledge and skills”), control (six items; e.g., “My teacher was less kind to those who did not try to see things his/her way”), and ego-involving climate (three items; e.g., “The teacher encourages students to outperform others”). Responses are given on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Academic engagement

The Spanish version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Student Scale (UWES-S; Schaufeli et al., 2002) was used. The UWES-S comprises 17 items grouped into three factors: vigor (six items; e.g., “I feel strong and vigorous in my studies”), dedication (five items; e.g., “My studies are stimulating and inspiring”), and absorption (six items; e.g., “I am immersed and engrossed in my studies”). Responses were given on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In this study, academic engagement was used as a higher-order factor, as in previous research (López-García et al., 2022).

Intention to choose teaching as a career

The Spanish version of the Future Teaching Intention Scale (FTIS; Burgueño et al., 2022), based on Fishbein and Ajzen (2010), was used. This instrument includes three items (e.g., “I am determined to work as a teacher in the next 3 years”) that assess pre-service teachers’ future intention to become teachers. Responses were given on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (extremely unlikely) to 7 (extremely likely).

Professional Teaching Identity (PTI)

The Spanish version (Granero-Gallegos et al., 2025) of Fisherman and Weiss’s (2008) Student Teachers Professional Identity Scale was used to assess teaching identity. This instrument consists of nine items (e.g., “Being a teacher is an important part of my life”) with responses on a Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Procedure

First, the academic coordinators of the MAES at each university were contacted to request their collaboration and to provide information about the aims and characteristics of the project. Next, students were contacted by email and invited to complete an online questionnaire. The form outlined the study aims, the anonymity of their responses, and how to complete the scales. It also explained that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any impact on their academic performance. To ensure the quality of the online responses, the questionnaire was configured so that items could not be left unanswered, thereby avoiding missing data. A minimum reasonable completion time was set to detect excessively rapid responses, and response patterns were screened for inconsistencies. The risk of automated responses was minimized by distributing the link only to institutional email addresses. In total, 478 responses were recorded, and all participants provided informed consent before completing the questionnaire. The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Almería (Ref.: UALBIO2021/009).

Sample Size

An a priori power analysis was conducted to determine the required sample size using the Free Statistics Calculator (v.4.0) software. A minimum of 472 students was needed to detect effect sizes of f2 = .20 with a statistical power of 90% and a significance level of α = .05 in a structural equation model (SEM) with five latent variables and 20 observed variables.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS (v.29) was used to calculate descriptive statistics, skewness, kurtosis, reliability (McDonald’s omega), and correlations between factors (Ibáñez-López et al., 2024).

The hypothesized predictive relationships of (dis)empowering climates with teaching identity, with multiple mediation by academic engagement and intention to become a teacher, were tested using a latent-variable SEM performed with AMOS (v.29) (Sánchez-Martín et al., 2024b).

The analysis followed a two-step approach. First, a saturated model was examined, in which all dimensions were interrelated. Second, the predictive relationships in the hypothesized model were evaluated. In the SEM, university and gender were included as covariates, and model fit was assessed using the following indices: chi-square/ degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) with its 90% confidence interval (CI), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Acceptable values are χ2/df < 5.0, CFI and TLI > .90, RMSEA < .08, and SRMR < .08 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2021).

Maximum likelihood estimation with a bootstrapping procedure of 5,000 resamples was used due to the lack of multivariate normality (Mardia’s coefficient = 134.15; p < .001) (Kline, 2023). Indirect effects and their 95% CI were estimated using bootstrapping, and an indirect effect was considered significant (p < .05) when its 95% CI did not include zero (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). McDonald’s omega (w) values > .70 were considered to indicate good reliability (Viladrich et al., 2017).

Finally, explained variance (R²) was considered as an effect size (ES; Dominguez-Lara, 2017), with values < .02 interpreted as small, around .13 as medium, and > .26 as large. In addition, 95% CIs for R2 were used to ensure that no value fell below the minimum required for interpretation (.02).

Results

Participants

A total of 478 students (44.8% women, 54.8% men, and 0.2% another gender) enrolled in the PE specialization of the MAES from several public universities participated. Their ages ranged from 21 to 47 years (M = 27.09; SD = 6.32). Data were collected in May 2022 and there were no missing values.

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the study variables, as well as reliability values (w) and correlations between dimensions.

Main Analyses

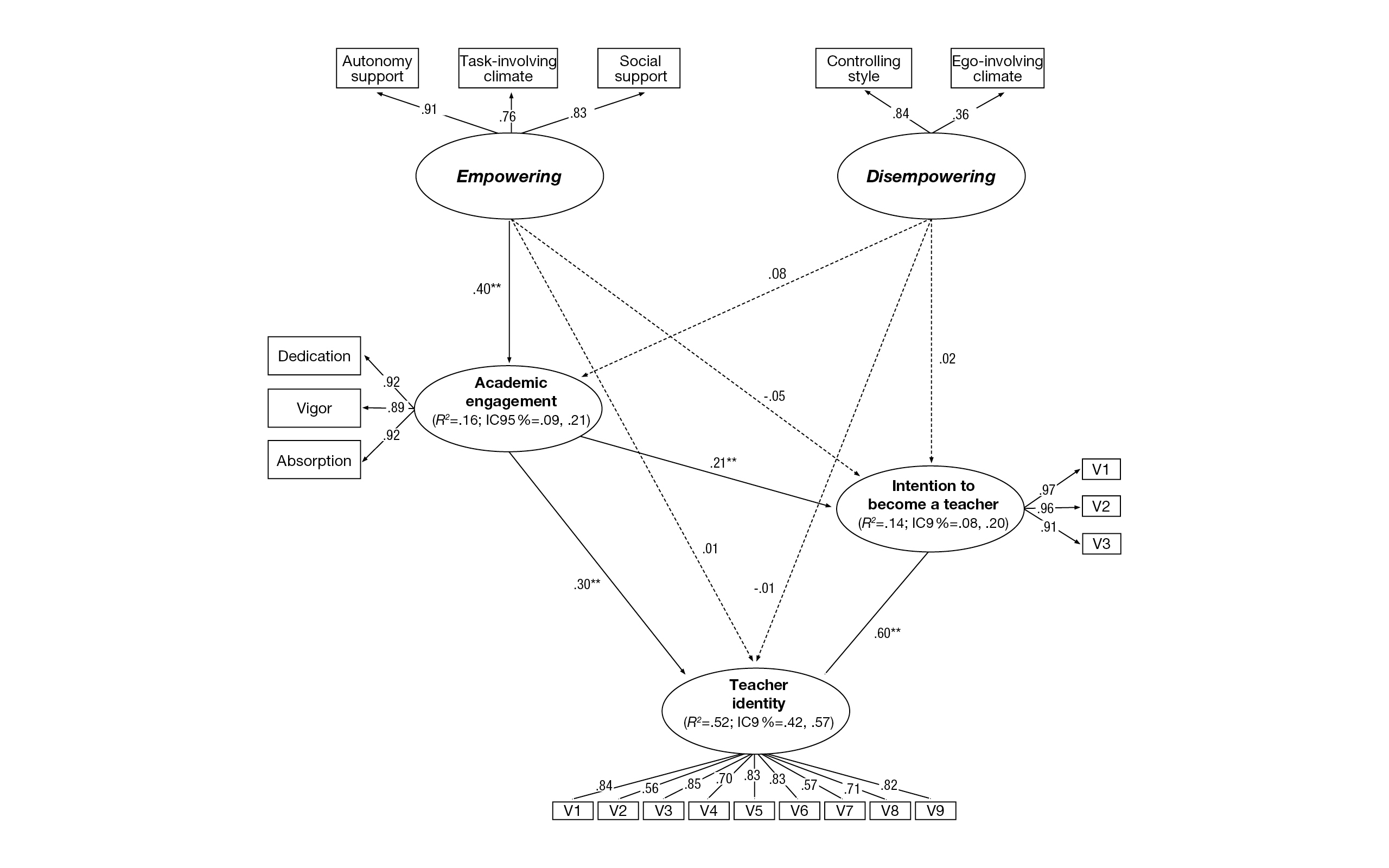

In step 1, the SEM showed acceptable fit indices: χ2/df = 2.62, p < .001; CFI = .96; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .058 (90% CI = .052–.065); SRMR = .047. In step 2, the hypothesized SEM also showed acceptable fit: χ2/df = 2.61, p < .001; CFI = .96; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .058 (90% CI = .052–.065); SRMR = .047. Explained variance was 52% for teaching identity (large), 16% for academic engagement (medium), and 14% for intention to become a teacher (medium), indicating an adequate level of explained variance for the latent variables considered (Dominguez-Lara, 2017).

As shown in Figure 2, academic engagement plays an important mediating role between empowering climate and teaching identity. No significant direct predictive relationships were found between disempowering climate and the other variables included in the SEM (academic engagement, p = .088; intention to become a teacher, p = .527; teaching identity, p = .560). The direct relationships between empowering climate and teaching identity (p = .869) and between empowering climate and intention to become a teacher (p = .346) were also not significant. In the SEM, however, there was a significant and positive direct predictive relationship between empowering climate and academic engagement (p < .001), between academic engagement and intention to become a teacher (p < .001), and between intention to become a teacher and teaching identity (p < .001). As can be seen, academic engagement is an important variable for improving teaching identity, as it significantly and positively mediates the relationship between empowering climate and teaching identity (β = .12; p < .001). Finally, Figure 2 displays the 95% CIs for R2, confirming that these values can be considered measures of ES (Dominguez-Lara, 2017), and all of them are large.

Note. **p < .001. The dashed lines represent non-significant relationships.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze the relationship between (dis)empowering motivational climates and teaching identity, considering the mediating role of academic engagement and intention to become a teacher in future PE teachers. The main results showed that empowering climate has an indirect and positive effect on teaching identity, highlighting the mediation of both academic engagement and intention to become a teacher.

The main findings revealed that (dis)empowering motivational climates do not directly predict personal teaching identity among future PE teachers. These results, which are inconsistent with previous studies (Day, 2011), may be due to the limited effect that socially situated influences (motivational climate) have on the development and construction of professional teaching identity in these pre-service teachers (Martín-Gutiérrez et al., 2014). A context that promotes extrinsic sociogenetic elements without personal influences that support them will not foster the development of teaching identity. As authors such as Beg et al. (2021) note, identity construction involves ongoing negotiation between external influences and the person; therefore, (dis)empowering climates will exert an influence only when dimensions inherent to teacher education are taken into account. Another possible explanation for these results lies in the cross-sectional nature of the study, since examining socio-contextual classroom climates at a single time point may not sufficiently capture the development of teaching identity. Future research should address the influence of (dis)empowering climates throughout the teacher education process (e.g., during the MAES) and examine how classroom climates affect the construction of professional teaching identity.

The SEM shows that an empowering climate indirectly predicts teaching identity through the mediating role of academic engagement and through intention to become a teacher, which in turn is preceded by academic engagement. Although both mediation paths are weak, the effect of academic engagement between empowering climate and professional identity is greater than the mediating effect of intention to become a teacher preceded by academic engagement. It is noteworthy that the direct predictive relationship between empowering climate and intention to become a teacher was not significant. According to the literature, intention to engage in teaching is a key cognitive element for future professional practice in pre-service teachers (Burgueño et al., 2022; López-García et al., 2023). Based on the conceptualization of the Theory of Planned Behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010), empowering climate would be expected to affect pre-service teachers’ perceived behavioral control, thereby increasing the antecedent of future behavior. However, our results do not fully fit this conceptualization, as a cognitive component such as academic engagement is needed to stimulate intention toward teaching (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Academic engagement thus acts as a fundamental pillar, not only to increase intention toward the teaching profession but also to foster identification with a teaching career.

Consistent with the hypothesized model, the results showed no mediating role of intention to become a teacher or academic engagement in the relationship between disempowering climate and teaching identity. These findings do not align with previous research, such as López-García et al. (2023), who reported that a disempowering climate in a sample of pre-service teachers from different specializations (PE, history, biology, geology, mathematics, etc.) positively predicted intention to become a teacher. The inconsistency between our results and those of the aforementioned study may be related to the influence of the disciplinary field, in this case PE. According to Crum (2012) and Saiz-González et al. (2025), PE is a subject that does not always aim to foster learning, which may lead future teachers to adopt pre-established identities based on social norms rather than on the performance of teaching duties (Gray & Morton, 2018). Another possible explanation is the lack of a social dimension (coldness) in Duda and Appleton’s (2016) theoretical conceptualization of a disempowering climate. Their model comprises three dimensions for empowering climate (autonomy support, task-involving climate, and social support) and two for disempowering climate (ego-involving climate and controlling style). The absence of a social dimension in disempowering climate may thus mean that less self-determined motivational climates do not foster teaching identity in future PE teachers.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its contribution, this study had several limitations. First, it relied on self-reports from PE pre-service teachers, which may lead to subjective responses regarding motivational climates. Moreover, this type of instrument may be subject to social desirability bias, especially in sensitive areas such as teaching identity. Future research should examine perceptions of motivational climates by combining different data collection tools (e.g., interviews, focus groups) and by including responses from teacher educators themselves.

Second, a non-random convenience sample was used, which limits the interpretation and generalization of the findings to the broader educational community. Future studies should examine the role of motivational climates in teaching identity across different pre-service teacher specializations.

Third, relevant contextual variables that might have influenced the results—such as the mode of instruction (e.g., face-to-face or online) or the characteristics of the university teachers responsible for the courses—were not controlled.

Fourth, authors such as Granero-Gallegos et al. (2024) and Espinoza-Gutiérrez et al. (2024) have highlighted the versatility of motivational processes in pre-service teachers. Future research should therefore use longitudinal designs to examine fluctuations in motivational processes and their impact on professional teaching identity.

Practical Implications

The findings of this study deepen and broaden our understanding of the role of motivational climates in developing teaching identity in PE pre-service teachers. They expand the evidence base supporting recommendations that PE teacher education programs foster empowering motivational climates. In addition, PE teacher educators should receive training on how to implement empowering climates that can stimulate the development of teaching identity.

To establish an empowering climate (see Appleton et al., 2016), PE teacher educators should apply strategies that include, among other aspects, providing social support to students (e.g., regularly implementing mentoring programs), promoting autonomy in learning (e.g., offering opportunities for choice), and fostering a learning-oriented environment (e.g., explaining the underlying usefulness of the proposed activities) (García-Fariña & Vázquez-Manrique, 2025; Ocete et al., 2025).

The findings of the present study suggest that creating and using such motivational strategies may promote the development of cognitive and intentional behaviors and, consequently, the development of professional teaching identity. In this regard, specific learning strategies such as service-learning and project-based learning, which are capable of developing specific teaching skills in future PE teachers, have gained increasing relevance in teacher education (Lobo-de-Diego et al., 2024; García-Fariña et al., 2024; Valldecabres & López, 2024).

Conclusions

In conclusion, to strengthen teaching identity in future PE teachers, it is necessary to create classroom contexts that foster academic engagement through empowering climates. PE teacher educators should therefore generate empowering classroom climates that build students’ academic engagement in order to promote the development of a professional identity throughout their teacher education.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the R&D&I project “Is the empowering–disempowering motivational climate perceived by undergraduate students related to their intention to become teachers? A longitudinal study of pre-service teachers” (Ref.: P20_00148), funded by the Andalusian Plan for Research, Development and Innovation (PAIDI 2020) of the Regional Government of Andalusia.

References

[1] Ames, C. (1992). Classroom: Goals, Structures, and Student Motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 261–271. doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.84.3.261

[2] Appleton, P.R., Ntoumanis, N., Quested, E., Viladrich, C., & Duda, J.L. (2016). Initial validation of the coach-created Empowering and Disempowering Motivational Climate Questionnaire (EDMCQ-C). Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 22, 53–65. doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.05.008

[3] Beg, S., Fitzpatrick, A., & Lucas, A.M. (2021). Gender Bias in Assessments of Teacher Performance. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 111, 190–195. doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20211126

[4] Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2009). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2), 107–128. doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001

[5] Burgueño, R., González-Cutre, D., Sicilia, Á., Alcaraz-Ibáñez, M., & Medina-Casaubón, J. (2022). Is the instructional style of teacher educators related to the teaching intention of pre-service teachers? A self-determination theory perspective-based analysis. Educational Review, 72(7), 1282–1304. doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1890695

[6] Crum, B. (2012). La crisis de identidad de la Educación Física: Diagnóstico y explicación. Educación Física y Ciencia 14, 61-72. In Memoria Académica. www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/art_revistas/pr.5667/pr.5667.pdf

[7] Day, C. (2011). Uncertain professional identities: Managing the emotional contexts of teaching. In Day, C., Lee, JK. (Eds), New understandings of teacher’s work: Emotions and educational change, (1st. ed., Vol. 100, pp. 45-64). Springer, Dordrecht. doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0545-6_4

[8] Dominguez-Lara, S. (2017). Effect size in regression analysis. Interacciones, 3(1), 3–5. doi.org/10.24016/2017.v3n1.46

[9] Duda, J. L., & Appleton, P. R. (2016). Empowering and disempowering coaching climates: Conceptualization, measurement considerations, and intervention implications. In Raab, M., Wylleman, P., Seiler, R., Elbe, A.M. & Hatzigeorgiadis, A. (Eds.) Sport and exercise psychology research (1st Ed., pp. 373-388). Academic Press. doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803634-1.00017-0

[10] Espinoza-Gutiérrez, R., Baños, R., Calleja-Núñez, J.J., & Granero-Gallegos, A. (2024). Effect of Teaching Style on Academic Self-Concept in Mexican University Students of Physical Education: Multiple Mediation of Basic Psychological Needs and Motivation. Espiral Cuadernos del Profesorado, 17(36), 46–61. doi.org/10.25115/ecp.v17i36.10087

[11] Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. In Ajzen, I., Albarracin, D., Hornik, R. (Eds.) Prediction and Change of Health Behavior: Applying the reasoned action approach (1st Ed., pp.3-21). Psychology Press.

[12] Fisherman, S., & Weiss, I. (2008). Consolidation of professional identity by using dilemma among pre-service teachers. Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 31–50. shre.ink/rjep

[13] García-Fariña, A. & Vázquez-Manrique, M. (2025). Communicative profile of physical education teachers in Secondary Education. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 161, 23–31. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2025/3).161.03

[14] García-Fariña, A., Gómez-Rijo, A., Fernández-Cabrera, J. M., & Jiménez-Jiménez, F. (2024). Perception of those responsible for a juvenile justice centreregardinga service-learning experience in physical activity and sports. Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 17(35), 47–57. doi.org/10.25115/ecp.v17i35.9705

[15] Granero-Gallegos, A., Baena-Extremera, A., Ortiz-Camacho, M.M., & Burgueño, R. (2023). Influence of empowering and disempowering motivational climates on academic self-concept amongst STEM, social studies, language, and physical education pre-service teachers: a test of basic psychological needs. Educational Review, 76(7), 2020-2042. doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2023.2290444

[16] Granero-Gallegos, A., Carrasco-Poyatos, M., Rubio-Valdivia, J.M., & López-García, G. (2025). Adaptation of the teacher-professional identity scale for initial teacher training in physical education, STEM, social-linguistic and artistic fields to the Spanish context. Espiral. Cuadernos del profesorado, 18(38), 49–65. doi.org/10.25115/ecp.v18i38.10199

[17] Granero-Gallegos, A., López-García, G.D., & Burgueño, R. (2024). Predicting the pre-service teachers’ teaching intention from educator-created (dis)empowering climates: A self-determination theory-based longitudinal approach. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 29(2), 118-129. dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psicoe.2024.01.001

[18] Gray, J. & Morton, T. (2018). Social Interaction and English Language Teacher Identity. Edinburgh University Press.

[19] Ibáñez-López, F. J., Rubio-Aparicio, M., Pedreño-Plana, M., & Sánchez-Martín, M. (2024). Descriptive statistics and basic graphs tutorial to help you succeed in statistical analysis. Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 17(36), 88–99. doi.org/10.25115/ecp.v17i36.9570

[20] Kline, R.B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (5th ed.). The Guilford Press.

[21] Lobo-de-Diego, F.E., Monjas-Aguado, R., & Manrique-Arribas, J.C. (2024). Experiences of Service-Learning in the initial training of physical education teachers. Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 17(35), 58–68. doi.org/10.25115/ecp.v17i35.9688

[22] López-García, G. D., Carrasco-Poyatos, M., Burgueño, R., & Granero-Gallegos, A. (2022). Teaching style and academic engagement in pre-service teachers during the COVID-19 lockdown: Mediation of motivational climate. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 992665. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.992665

[23] López-García, G.D., Granero-Gallegos, A., Carrasco-Poyatos, M., & Burgueño, R. (2023). Detrimental effects of disempowering climates on teaching intention in (physical education) initial teacher education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 878, 8–14. doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010878

[24] Martín-Gutiérrez, A., Conde-Jiménez, J. & Mayor-Ruiz, C. (2014). La identidad profesional docente del profesorado novel universitario. REDU - Revista de Docencia Universitaria, 12(4), 141–160. doi.org/10.4995/redu.2014.5618

[25] Milton, D., Appleton, P. R., Quested, E., Bryant, A., & Duda, J. L. (2025). Examining the mediating role of motivation in the relationships between teacher-created motivational climates and quality of engagement in secondary school physical education. PloS One, 20(1), e0316729. dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0316729

[26] Milton, D., Appleton, P., Bryant, A., & Duda, J. L. (2025). Promoting a More Empowering Motivational Climate in Physical Education: A Mixed-Methods Study on the Impact of a Theory-based Professional Development Programme. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1564671. dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1564671

[27] Ocete, C., González-Peño, A., Gutiérrez-Suárez, A., & Franco, E. (2025). The effects of a SDT-based training program on teaching styles adapted to inclusive Physical Education. Does previous contact with students with intellectual disabilities matter? Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 18(37), 1–14. doi.org/10.25115/ecp.v18i37.10242

[28] OECD (2020). TALIS 2018 Results (Volume II): Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals, TALIS, OECD Publishing. Paris. doi.org/10.1787/19cf08df-en

[29] Pittaway, S., & Moss, T. (2013). Dimensions of engagement in teacher education: From theory to practice. Refereed paper presented at ‘Knowledge makers and notice takers: Teacher education research impacting policy and practice’, the annual conference of the Australian Teacher Education Association (ATEA), Brisbane, 30 June–3 July.

[30] Reeves, J. (2018). Teacher Identity. In Liontas, J.I., T. International Association & DelliCarpini, M. (Eds.) The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching, (pp. 1-7). Wiley-Blackwell. doi.org/10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0268

[31] Rubio-Valdivia, J. M., Granero-Gallegos, A., Carrasco-Poyatos, M., & López-García, G.D. (2024). The Mediating Role of Teacher Efficacy Between Academic Self-Concept and Teacher Identity Among Pre-Service Physical Education Teachers: Is There a Gender Difference? Behavioral Sciences, 14(11), 1053. dx.doi.org/10.3390/bs14111053

[32] Ryan, R.M., & Deci, E.L. (2017). Self-determination theory. Basic psychological needs in motivation, development and wellness. Guilford Publications. doi.org/10.1521/978.14625/28806

[33] Saiz-González, P., Iglesias, D., Coto-Lousas, J. & Fernandez-Rio, J. (2025). Exploring pre-service teachers’ negative memories of physical education. Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 18(37), 47–59. doi.org/10.25115/ecp.v18i37.10033

[34] Sánchez-Martín, M., Ponce Gea, A. I., Rubio Aparicio, M., Navarro-Mateu, F., & Olmedo Moreno, E. M. (2024a). A practical approach to quantitative research designs. Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 17(35). doi.org/10.25115/ecp.v17i35.9725

[35] Sánchez-Martín, M., Olmedo Moreno, E. M., Gutiérrez-Sánchez, M. & Navarro-Mateu, F. (2024b). EQUATOR-Network: a roadmap to improve the quality and transparency of research reporting. Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 17(35), 108–116. doi.org/10.25115/ecp.v17i35.9529

[36] Schaufeli, W.B., Martínez, I.M., Marqués-Pinto, A., Salanova, M., & Barker, A. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students a cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 464–481. doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005003

[37] Shrout, P.E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

[38] Simon, L., Mastagli, M., Girard, S., Bolmont, B., & Hainaut, J. P. (2025). Motivational Climate in Physical Education: How Anxiety and Pleasure Modulate Concentration and Distraction. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 1(aop), 1-9. doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2024-0256

[39] Tabachnick, B.G., & Fidell, L.S. (2021). Using Multivariate Statistics (7th ed.). Pearson

[40] Valldecabres, R., & López, I. (2024). Learning-service in High-school: Systematic review from physical education. Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 17(35), 33–46. doi.org/10.25115/ecp.v17i35.9659

[41] Viladrich, C., Angulo-Brunet, A., & Doval, E. (2017). A journey around alpha and omega to estimate internal consistency reliability. Annals of Psychology, 33(3), 755–782. doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.3.268401

[42] Von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Vandenbrouckef, J. P. (2007). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 85(11), 867–872. doi.org/10.2471/BLT.07.045120

[43] Wong, C.E., & Liu, W.C. (2024). Development of teacher professional identity: perspectives from self-determination theory. European Journal of Teacher Education, 1–19. doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2024.2371981

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: April 4, 2025

Accepted: July 23, 2025

Published: January 1, 2026

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en