How do coaches convey their instructions? Analyzing content and associated emotions

*Corresponding author: Lídia Ordeix lidia.ordeix@uab.cat

Cite this article

Ordeix, L., Viladrich, C. & Alcaraz, S. (2025). How do coaches convey their instructions? Analyzing content and associated emotions. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 160, 49-58. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2025/2).160.06

Abstract

Imparting technical instruction and feedback is the most commonly seen behavior in coaches. However, research has focused on the pedagogical content of those instructions and neglected how those interactions occur. The aim of this study was to assess how coaches give instruction and feedback to athletes, taking into consideration the content of instructions and the associated emotions. To that end, we observed and recorded the behavior of eight coaches (four women and four men) during female athletes’ sports competitions. To do so we used the Assessment of Coach Emotions (ACE) observational tool that evaluates the content, emotion, and the recipient subject of a coach’s behavior. We employed lag sequential analysis, the results of which showed that, when giving instruction and feedback, the eight coaches presented similar behavior, and said behavior was preceded and followed by alternating observational behaviors. In addition, the coaches’ observed emotions when giving instruction and feedback were ‘alert’ and ‘tense,’ while the emotions associated with observation were ‘neutral’ and ‘anxious.’ These findings revealed similarities in the behavioral sequences and emotions associated with giving instruction and feedback and with observation in the assessed coaches. This approach provided information that could greatly improve training effectiveness.

Introduction

Interactions between coaches and athletes have been a topic of study in sports psychology for decades (Smith & Smoll, 1996; Mesquita et al., 2005) and continue to represent a field of interest today (Porto et al., 2021; Ordeix et al., 2023). One of the main research aims in this field is to describe coaching behavior within different sports and contexts (Davis & Davis, 2016), as its impact on youth sports is fundamental and widely recognized, and significantly affects athletes’ development and athletic experience (Bloom et al., 2020). From the perspective of self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985), coaches influence the satisfaction or frustration of athletes’ basic psychological needs (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness), which in turn predicts direct differences in their physical and psychological wellbeing (Cantú-Berrueto et al., 2016; Deci & Ryan, 2000). Studies show that coaches exhibit a wide range of behaviors when interacting with athletes, and emphasize the importance of instruction, support, reinforcement, and management within their repertoire of behaviors (Erickson & Gilbert, 2013). Specifically, previous research has underscored instruction-based behavior as predominant among coaching actions (Curtis et al., 1979; Ford et al., 2010), which shows that these behaviors are an effective way of supporting the athletes’ learning and performance (Petancevski et al., 2022). Over the years, coaching behavior has been studied from various perspectives to demonstrate its impact on the athletic experience of athletes by means of interpersonal communication (LaVoi, 2007), motivational climate (Newton et al., 2000), leadership (Álvarez et al., 2010), and emotions (van Kleef et al., 2019).

A number of observation instruments have been used to assess and evaluate coaches’ behaviors (Vierimaa et al., 2016). The results show that coaches exhibit a wide range of behaviors when interacting with athletes, including giving instruction, encouragement, and reinforcement, as well as management behaviors, these being distinctive traits of effective coaches (Erickson & Gilbert, 2013). In this sense, previous research in different sports disciplines has indicated that technical interactions with the team, such as giving instruction and feedback, are the most commonly used coaching behaviors (Cushion & Jones, 2001) and represent an effective way of supporting athlete learning and performance (Petancevski et al., 2022). While it can be argued that giving instruction and feedback is an essential part of coaching (Becker, 2013), effectiveness depends on quality and prudent application, rather than rigid implementation of generic coaching skills (Cushion & Jones, 2001).

In recent decades, research on coaching behavior has been criticized for overly focusing on pedagogical content, thus neglecting more subjective qualities associated with interactive behavior (Horn, 2008). The publication of new instruments has started to meet the demand for observation protocols for more sensitive and contextualized behavior (Corbett et al., 2023). These include increasing research into the emotional processes and dynamic and interpersonal nature of emotion (van Kleef et al., 2019), which emphasizes the essential role of emotions in coach-athlete interactions (Davis & Davis, 2016). The Assessment of Coach Emotions observation tool was developed to be able to evaluate this behavior (ACE; Allan et al., 2016). The ACE tool assesses observable emotions in coaches, as well as the content of their interactions and the recipient subjects with whom they interact (see Allan et al., 2016, for a detailed description). Within this context, Ordeix et al. (2024) recently adapted the ACE tool to the Spanish cultural context (ACE-E) and presented their data on application of the tool. This study notes the importance of taking into account the emotions associated with coaches’ behavior and highlights the lack of studies addressing this interaction between content and emotion. The Ordeix et al. (2024) study also differs in that it assessed the coaches’ behavior by incorporating fundamental parameters such as frequency and order, as proposed by Anguera & Hernández-Mendo (2015), similar to other recent sports science studies (Flores-Rodríguez & Alvite-de-Pablo, 2023). This approach was achieved through a multivariate analysis known as lag sequential analysis (Bakeman, 1978), which allows for sequential patterns to be detected in observed behaviors. This analysis offers a refined perspective of the study of coaching behaviors, suggesting patterns of behavior and relationships between different coaching action variables, such as instructional behavior or the use of silence, based on descriptive analysis and the rate of behavior per minute. (Cushion & Jones, 2001).

The Ordeix et al. (2024) study assessed the behavior of eight coaches, considering the content of the behavior, emotions, and relationships between the different codes. The results were conjointly presented and polar coordinates analysis was used (Sackett, 1980) to illustrate the usefulness of the ACE-E. This study, on the other hand, used the same sample to individually break down the data using lag sequential analysis. This strategy enabled us to identify patterns and relationships that may not have been evident through conjoint analysis (Sánchez-Algarra & Anguera, 2013). The sample included male and female coaches of women’s sports with the aim of obtaining data about this setting, which traditionally has been less studied compared to men’s sports (Cushion & Jones, 2001). Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze the individual behavior of giving instruction and feedback by the participating coaches using a descriptive approach and considering the content and emotions associated with said behavior. To achieve this, three specific objectives were defined: (a) describe the behavior sequences of the eight coaches; (b) examine the repertoire of emotions that are exhibited when giving instruction; and (c) examine the repertoire of emotions exhibited in the behaviors presented before and after giving instruction.

Methodology

Research design

We used observational methodology with a one-off nomothetic multidimensional design according to the criteria defined by Anguera et al. (2011). Nomothetic due to the differential analysis of the plurality of the coaches, and one-off because only a single competition was recorded for each coach. However, the monitoring was intrasessional and multidimensional, as different levels of response collected in the instrument were observed.

Participants

The sample was made up of eight coaches (four women and four men) of female athletes participating in various national sports competitions. The participants (see Table 1 for a detailed summary) were between 18 and 54 years old (M = 29.25 years, SD = 11.22). All of them had obtained coaching qualifications in their respective sports.

The study participants were selected via convenience sampling and the accessible cases that met the inclusion criteria were selected. The criteria mandated that the sample include the same number of men and women, and the participants had to be coaches in any youth sports discipline in Spain.

This study is part of a project that was approved by the ethics committee of the university where the research was conducted.

Instruments

The Spanish adaptation of the Assessment of Coach Emotions (ACE) tool (Allan et al., 2016) was used (ACE-E; Ordeix et al., 2024). The scores provided by the instrument present positive reliability values with Kappa coefficients between .77 and .93 for the study data. Based on continuous coding, the ACE-E instrument assesses three dimensions of coaching behavior: (a) content; (b) emotions; and (c) recipient subject. Each dimension contains different behavior content codes.

Specifically, the content dimension refers to the type of behavior (e.g., giving instruction to an athlete) and is made up of 13 codes (organization, keeping control/standards of behavior, hustle, instruction/feedback, encouragement, positive evaluation, negative evaluation, questioning, general communication, communication with others, observation, not engaged, not engaged due to related tasks). The ‘instruction/feedback’ code is the variable addressed in this study and is defined by the authors of the tool as technical and/or tactical instruction and/or feedback from the coach, directed at the athletes’ motor and/or psychological skill execution or performance.

The emotion dimension includes eight codes (happy, affectionate, alert, neutral, tense, anxious, angry, disappointed), while the recipient subject dimension has seven codes (individual, team, assistant coach, family members, referee, self, others). Since this study focuses on the instructions and feedback given by coaches which correspond to the ACE ‘instruction/feedback’ content code, and since the recipient subject of the majority of this behavior is the female athletes, in this research the recipient code is always the athletes and we specifically focus on the content and emotion codes.

Observation software. The coaches’ behavior was logged during competition according to the codes and using the HOISAN program, version 1.6.3 (Hernández-Mendo et al., 2014), which allowed for the duration of each configuration to be recorded in time segments. The type of data used was multi-event, meaning the three categories were coded for each observation (content, emotion, and recipient). The same program was used to perform data quality analysis as well as the lag sequential analysis.

Procedure

The coaches were informed about the study’s research objectives, and they were asked to participate on a volunteer basis. They gave their informed consent in a prior meeting in which a short, semi-structured interview was held to collect sociodemographic data and information about their qualifications. The confidentiality of their data was guaranteed, and they were informed of the option to leave the study at any time.

This was followed by the data collection phase, which involved filming one game for each participant. In total, the database includes 500 minutes of audio and video recordings lasting between 60 and 90 minutes for each participant. In all cases, the observations and subsequent analyses were carried out by the initial author, who had previously received training on the tool (100 training hours) and who has 11 years of experience in the field as a coach and sports psychologist.

For more details, we recommend consulting the procedures section in Ordeix et al. (2024).

Data analysis

Sequential analysis. Different lag sequential analyses were conducted to provide a descriptive response to the three specific objectives. This technique allowed us to identify the presence of consistent patterns in the behavior of the evaluated coaches. To do so, we used the recommended cut-off point for values with an adjusted residual of > 1.96 (Bakeman, 1978).

With the aim of describing sequences of behavior for the eight coaches, the instruction/feedback code was selected as the benchmark behavior for analysis, meaning the behavioral category for which the successive interactions were recorded. Specifically, in this analysis the five interactions prior to and five interactions post the benchmark behavior were taken into account (lag -5, +5) and their relationship to the codes that refer to the behavior content (e.g., organization, keeping control/standards of behavior, hustle, instruction/feedback, encouragement, positive evaluation, negative evaluation, questioning, general communication, communication with others, observation, not engaged, not engaged due to related tasks) as paired behaviors.

Subsequently, to examine the repertoire of emotions that occur when the eight coaches give instruction, the same technique was applied, but this time in lag 0 and with the emotion codes (e.g., happy, affectionate, alert, neutral, tense, anxious, angry, disappointed) as paired codes for analyzing simultaneity or co-occurrence of emotions with giving instruction to respond to the second specific objective.

Lastly, to address the third objective, the behaviors identified in the first objective (those that make up the instruction sequence) were selected as the benchmark behavior and the paired emotions to analyze their simultaneity starting at lag 0 in the sequential analysis.

Results

The results are presented below, organized according to the specific study objective to which they respond.

Behavior sequences for the eight coaches

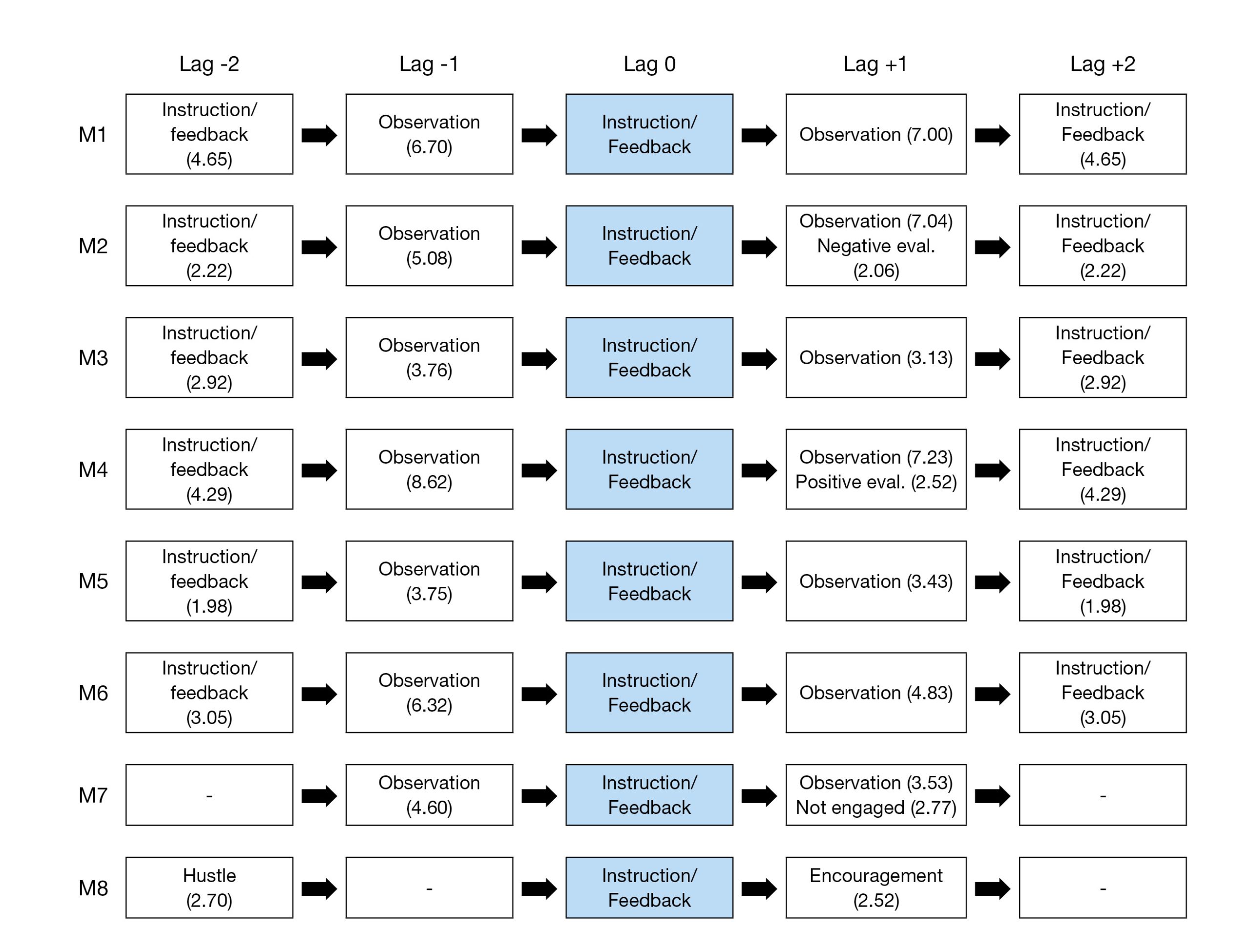

Considering the first specific study objective was to explore the behavior sequences of the eight coaches when giving instruction/feedback, the instruction/feedback content code was selected as the benchmark behavior, which is located at lag 0 in the action chain, and the adjusted residuals were calculated for the behaviors that were considered paired (all the content codes). Based on the positive adjusted residuals greater than 1.96, the behavior patterns were extracted for the eight coaches. Figure 1 shows the lags included because they presented a sequence with values higher than the cut-off point established for the evaluated coaches (from lag -2 to +3). The results reveal little variation among the coaches and represent the basic sequence of the study participants, characterized by the instruction/feedback and observation behaviors, with the exception of coach M8, who did not present a clear behavior sequence and exhibited hustle (lag -2), encouragement (+1), and general communication (+3).

Note. The lags with an absolute value-adjusted residual below the cut-off point are identified with a dash. M1 = coach 1, M2 = coach 2, M3 = coach 3, M4 = coach 4, M5 = coach 5, M6 = coach 6, M7 = coach 7, M8 = coach 8.

Analysis of emotions based on instructions and feedback

The second objective was to explore the eight coaches’ emotions in relation to giving instruction/feedback. To do this, a sequential analysis was conducted for lag 0, wherein the instruction/feedback code was considered the benchmark behavior, and the emotion codes were considered paired behaviors.

The results (Table 2) showed that in lag 0, where the instruction behavior occurs, the eight evaluated coaches exhibited the emotions ‘alert’ and ‘tense.’ The emotion ‘angry’ was also present in coach M3.

Table 2

Adjusted residuals of the lag sequential analysis for the eight coaches with instruction/feedback as the benchmark behavior and the paired emotion codes.

Analysis of the emotions associated with the coach’s behavior

The third specific objective was to explore the emotions associated with the behavior content that accompanies giving instruction in the eight coaches. Since the previous results showed that observation is the content that accompanied instruction in the lags prior and subsequent to the behavior of the evaluated coaches, the concurrence of this behavior with the other emotion codes was examined based on the sequential analysis of lag 0, in which the observation code was considered the benchmark behavior, and the emotion codes were considered paired behaviors.

The results (see Table 3) showed that in lag 0, when the observation behavior occurs, coaches M1, M5, M7 and M8 exhibited the ‘neutral’ emotion. Coach M2 exhibited the emotion ‘anxious,’ and coaches M3, M4, and M6 exhibited the emotions ‘neutral’ and ‘anxious.’

Table 3

Adjusted residuals of the lag sequential analysis for the eight coaches with observation as the benchmark behavior and the paired emotion codes.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the instruction/feedback behavior of eight women’s sports coaches during competition by means of descriptive analysis. To do this, the content of the behavior and the associated emotions were taken into account. The results showed that the evaluated coaches presented similar behavior sequences, wherein observation predominated in the sequences before and after giving instructions and feedback. On the other hand, we noted similarities in the emotions related to giving instructions and observation, wherein alert and tense emotions predominated in the former and neutral and anxious emotions in the latter. These findings provide empirical evidence of these relationships, which had not been previously specifically studied along the lines of the study from Ordeix et al. (2023).

First, the behavior sequence was described when giving instruction and feedback, which alternated between observation and instruction. This implies that the coaches first observed, then interacted with the athletes, and then observed again. These results fall in line with, from a more sophisticated analysis, those of Cushion & Jones (2001), who observed that coaches initiate an action and then stay silent, allowing for a period of free play before intervening again, and subsequently falling silent again. This is also in line with the study by Magill (1993), who suggested that silence is essential to the delivery of information, which guarantees careful and measured feedback, and that the effect of their interventions is not diluted by continuous interaction as it allows the athletes to participate in their own sensory feedback. The results showed that the evaluated coaches fill those silences by observing their athletes. This behavioral pattern can be interpreted as a process of prior analysis by the coaches before directly interacting with the athletes since, as described by Cushion & Jones (2001), these periods of observation offer the opportunity to analyze and reflect on the most appropriate interventions during a given interaction. The results from coach M8 deviated from the behavior pattern detected among the other coaches, which could be attributed to their secondary role in the technical team during the analyzed game, as this may have impacted their performance.

Second, we observed similar emotions associated with the instruction or feedback behavior among all eight coaches, with the predominant emotions being ‘alert’ and ‘tense.’ The presence of these emotions may suggest that the coaches experienced an emotional burden associated with their role, which could potentially indicate an activation or preparation reaction to their current task, in accordance with the circumplex model of affect from Russell (1980). These emotions are related to the attention and concentration needed to effectively communicate an instruction. These interpretations are in line with the description of these emotions as relatively neutral but maintain a slight positive valence in the case of the ‘alert’ emotion and a slight negative valence in the case of ‘tense,’ as per the authors of the tool (Allan et al., 2016). Likewise, the ‘angry’ emotion exhibited by coach M4 suggests elevated hustle, frustration, or irritation when giving instruction or feedback, which could impact their coaching/teaching style and interactions with the athletes. These findings are important for designing emotional support strategies and professional development targeted at coaches.

Lastly, the emotions associated with observation were explored, which were consistent among all the coaches assessed. The ‘neutral’ and ‘anxious’ emotions were most common among the assessed coaches during the observation period. Given that prior research has indicated that coaches dedicate a considerable portion of their activity to silent observation during competitions (Turnnidge, 2017), these findings highlight the importance of analyzing the emotions associated with said behavior. While the ‘neutral’ emotion predominates in some cases, in other coaches a tendency towards unpleasant emotions can also be observed. These results underscore the importance of individual evaluation that identifies the specific traits of each coach as a way to offer more effective assessment in terms of regulating emotions, since effective emotional regulation is closely tied to decision-making abilities (Harvey et al., 2015). The role of emotions in decision-making is extremely complex, as it can result in both positive and negative results, and a coach’s emotional state significantly impacts their decision-making (Laborde et al., 2013).

Inadequate emotional management can have adverse consequences (Stirling, 2013) and impact the effectiveness of the message that is being communicated. This is particularly relevant in intense emotional situations, as athletes view coaches as role models considering that they play such a crucial role in their emotional responses (e.g., Friesen et al., 2013). Previous studies indicate that coaches use different strategies to manage emotional demands. Frey (2007) notes that they use cognitive strategies (e.g., re-evaluation), emotional coping strategies (e.g., social support) and behavioral strategies (e.g., preparation) to manage stress. These strategies show the effort that coaches make to try to balance their resources with the demands they face. This study provides a perspective of how coaches cope with emotional demands and offers a path towards developing a coach assessment program that, on the one hand, takes into account the coaches’ communication style, in line with previous research (Cruz et al., 2011; Sousa et al., 2006) and, on the other hand, considers the coaches’ emotions, which would allow for the development of individualized emotional management programs.

This study stands out because it examined the behavior of coaches within the context of women’s sports, providing scientific evidence and increasing visibility, which is in line with recent studies (Ronkainen et al., 2020). In addition, we used the innovative technique that is lag sequential analysis, which broadens its application beyond studies focused on motor skills in sports science (Font et al., 2022). This technique offers the option to evaluate the dynamic nature of coaches’ emotions and improves our understanding of the contextual nuances, enabling us to explore relationships between various categories (Castellano & Hérnandez-Mendo, 2002). On the other hand, the use of HOISAN to conduct the data analysis, according to a common practice in recent observational methodology studies (Amatria et al., 2020; Ordeix et al., 2024), ensured data reliability by means of the direct calculation of Cohen’s Kappa coefficient (Hernández-Mendo et al., 2014).

Limitations

The limited number of recordings of each participant restricts generalization of the data obtained, as this was limited to one recording per coach. Having access to recordings from multiple games or competitions would allow us to better assess the consistency of the coaches’ behavior in different situations and settings, and would minimize the influence of uncontrolled variables, such as situational factors or measurement errors, which could impact coaches’ behavior at certain events and therefore reveal whether their behavior is consistent (Anguera et al., 2011). Likewise, it would be beneficial to broaden the sample to include greater representation of diversity within the sport, such as including coaches from a wider range of disciplines, including individual sports. This study only assessed coaches from three sports disciplines (soccer, basketball, and volleyball). Said diversity would contribute to painting a more representative and comprehensive picture of behavior patterns in the world of sports.

Another important limitation was that the study was confined to an observational methodology and was not supplemented with other quantitative and qualitative data collection techniques. The combination of these methodologies could provide a more holistic approach, which would allow for a more in-depth and detailed analysis of the coaches’ behaviors and attitudes, as well as the dynamics found in different sports settings.

Research prospects

For future research, it could be interesting to include the perspectives of the athletes themselves to assess how coaching behavior impacts their sports experience. The failure to evaluate how coaches’ actions impact the actual athletes was one of the study limitations we identified, so additional research is needed to examine the impact of said behavior. Similarly, taking into consideration the outcome of the game during the assessment may be useful in determining whether it impacts the coaches’ behavior, given that the study by Mason et al. (2020) suggested that feedback associated with enhanced learning and performance seems to be more frequent when the competition scoreboard is in your favor.

Lastly, continuing with this line of research and exploring coaches’ instruction or feedback behavior and their emotions in other cultural contexts would be extremely beneficial. Studying these variables in different cultures would allow us to understand how cultural factors impact coaching styles and coaches’ emotional management. What’s more, using this comparative approach in future research could reveal universal patterns or significant differences in strategies for giving instruction and in how emotion is expressed, thus enriching knowledge of how coaching techniques are adapted in diverse cultural settings.

Conclusions

The study results reveal a common behavior sequence among the evaluated coaches when giving instruction and feedback with observation as associated behavior. Giving instruction and feedback was associated with the ‘alert’ and ‘tense’ emotions, while the observation that takes place prior to the previous behavior was characterized by the ‘neutral’ and ‘anxious’ emotions. These findings provide empirical evidence of these relationships, which had not been previously studied, and highlight the importance of analyzing the emotions related to coaches’ behavior. This emphasizes the need for individual evaluation to provide a more effective assessment of emotional regulation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants for their contributions to the study. The research was conducted thanks to the RTI2018-095468-B-100 project from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities and the FI-SDUR (2020 FI SDUR00098) grant from the Government of Catalonia.

References

[1] Allan, V., Turnnidge, J., Vierimaa, M., Davis, P., & Côté, J. (2016). Development of the Assessment of Coach Emotions systematic observation instrument: A tool to evaluate coaches’ emotions in the youth sport context. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 11(6), 859–871. doi.org/10.1177/1747954116676113

[2] Álvarez, O., Castillo, I., & Falcó, C. (2010). Estilos de liderazgo en la selección española de taekwondo. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 19(2), 219–230.

[3] Amatria, M., Lapresa, D., Martín Santos, C., & Pérez Túrpin, J. A. (2020). Offensive Effectiveness in the Female Elite Handball in Numerical Superiority Situations. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte, 20(78), 227–242. doi.org/10.15366/rimcafd2020.78.003

[4] Anguera, M. T., Blanco, A., Hernández, A., & Losada, J. L. (2011). Diseños observacionales: ajuste y aplicación en psicología del deporte. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 11(2), 63–76.

[5] Anguera, M. T., & Hernández-Mendo, A. (2015). Data analysis techniques in observational studies in sport sciences. Cuadernos de Psicologia del Deporte, 15(1), 13–30. doi.org/10.4321/s1578-84232015000100002

[6] Bakeman, R. (1978). Untangling streams of behaviour: Sequential analysis of observation data. In G. P. Sackett (Ed.), Observing behaviour, Vol. 2: Data collection and analysis methods (pp. 63–78). Baltimore: University of Park Press.

[7] Becker, A. (2013). Quality coaching behaviours. In P. Potrac, W. Gilbert, & J. Denison (Eds.), Routledge handbook of sports coaching (pp. 184–195). Routledge.

[8] Bloom, G. A., Dohme, L.C., & Falcão, W. R. (2020). Coaching youth athletes. In R. Resende, & A. R. Gomes (Eds.), Coaching for human development and performance in sports (pp. 143–167). Springer.

[9] Cantú-Berrueto, A., Castillo, I., López-Walle, J., Tristán, J., & Balaguer, I. (2016). Estilo interpersonal del entrenador, necesidades psicológicas básicas y motivación: Un estudio en futbolistas universitarios mexicanos. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología del Ejercicio y el Deporte, 11(2), 263–270.

[10] Castellano, J., & Hérnandez-Mendo, A. (2002). Aportaciones del análisis de coordenadas polares en la descripción de las transformaciones de los contextos de interacción defensivos en fútbol. Kronos: Revista Universitaria de la Actividad Física y el Deporte, 1(1), 42–48.

[11] Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

[12] Corbett, R., Partington, M., Ryan, L., & Cope, E. (2023). A systematic review of coach augmented verbal feedback during practice and competition in team sports. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 1–18. doi.org/10.1177/17479541231218665

[13] Cruz, J., Torregrosa, M., Sousa, C., Mora, A., & Viladrich, C. (2011). Efectos conductuales de programas personalizados de asesoramiento a entrenadores en estilos de comunicación y clima motivacional. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 20(1), 179–195.

[14] Curtis, B., Smith, R. E., & Smoll, F. L. (1979). Scrutinizing the Skipper: A study of leadership behaviors in the dugout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64(4), 391–400. doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.64.4.391

[15] Cushion, C., & Jones, R. (2001). A systematic observation of professional top-level youth soccer coaches. Journal of Sport Behavior, 24(4), 354–376.

[16] Davis, P. A., & Davis, L. (2016). Emotions and emotion regulation in coaching. In P. A. Davis (Ed.), The psychology of effective coaching and management. Sports and athletics preparation, performance and psychology. (Issue July, pp. 285–307). Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

[17] Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109–134. doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6

[18] Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

[19] Erickson, K., & Gilbert, W. (2013). Coach-athlete interactions in children’s sport. In J. Côté & R. Lidor (Eds.), Conditions of children’s talent development in sport (pp. 139–156). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

[20] Flores-Rodríguez, J., & Alvite-de-Pablo, J. (2023). Offensive Performance Indicators of the Spanish Women’s Handball Team in the Japan 2019 World Cup. Apunts. Educacion Fisica y Deportes, 152, 70–81. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2023/2).152.08

[21] Font, R., Daza, G., Irurtia, A., Tremps, V., Cadens, M., Mesas, J. A., & Iglesias, X. (2022). Analysis of the Variables Influencing Success in Elite Handball with Polar Coordinates. Sustainability, 14(23), 15542. doi.org/10.3390/su142315542

[22] Ford, P. R., Yates, I., & Williams, M. (2010). An analysis of practice activities and instructional behaviours used by youth soccer coaches during practice: Exploring the link between science and application. Journal of Sports Sciences, 28(5), 483–495. doi.org/10.1080/02640410903582750

[23] Frey, M. (2007). College coaches’ experiences with stress “problem solvers” have problems, too. The Sport Psychologist, 21, 38–57. doi.org/10.1123/tsp.21.1.38

[24] Friesen, A. P., Lane, A. M., Devonport, T. J., Sellars, C. N., Stanley, D. N., & Beedie, C. J. (2013). Emotion in sport: Considering interpersonal regulation strategies. International review of sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(1), 139–154. doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2012.742921

[25] Harvey, S., Lyle, J. W. B., & Muir, B. (2015). Naturalistic Decision Making in High Performance Team Sport Coaching. International Sport Coaching Journal, 2(2), 152–168. doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2014-0118

[26] Hernández-Mendo, A Castellano, J., Camerino, O., Jonsson, G., Blanco-Villaseñor, Á., Lopes, A., & Anguera, M. (2014). Programas informáticos de registro, control de calidad del dato, y análisis de datos. Revista de Psicología Del Deporte, 23(1), 111–121.

[27] Horn, T. S. (2008). Coaching effectiveness in the sport domain. In T. S. Horn (Ed.), Advances in sport psychology (3rd ed.) Human Kinetics.

[28] Laborde, S., Dosseville, F., & Raab, M. (2013). Introduction, comprehensive approach, and vision for the future. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(2), 143–150. doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2013.773686

[29] LaVoi, N. M. (2007). Interpersonal communication and conflict in the coach-athlete relationship. In S. Jowett & D. E. Lavalle (Eds.), Social Psychology in Sport (1st ed., pp. 29–40). Champaign: Human Kinetics.

[30] Lyle, J. 2002. Sports coaching concepts: a framework for coaches’ behaviour. London: Routledge

[31] Magill, R. A. (1993). Modeling and verbal feedback influences on skill learning. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 24(4), 358–369.

[32] Mason, R. J., Farrow, D., & Hattie, J. A. C. (2020). An analysis of in-game feedback provided by coaches in an Australian Football League competition. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 25(5), 464–477. doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2020.1734555

[33] Mesquita, I., Rosa, G., Rosado, A., & Moreno, M. P. (2005). Análisis de contenido de la intervención del entrenador de voleibol en la reunión de preparación para la competición Estudio comparativo de entrenadores de equipos senior masculinos y femeninos

[34] Newton, M., Duda, J. L., & Yin, Z. (2000). Examination of the psychometric properties of the perceived motivational climate in sport questionnaire-2 in a sample of female athletes. Journal of Sports Sciences, 18(4), 275–290. doi.org/10.1080/026404100365018

[35] Ordeix, L., Viladrich, C., & Alcaraz, S. (2023). Comparing three observation instruments of the coach’s behaviour in grassroots football. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 18(6), 1901–1912. doi.org/10.1177/17479541231189647

[36] Ordeix, L., Alcaraz, S., Belza, H., & Viladrich, C. (2024). Cultural adaptation of the Assessment of Coach Emotions to the Spanish sports context (ACE-E). International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 19(4), 1395–1405. doi.org/10.1177/17479541241247005

[37] Petancevski, E. L., Inns, J., Fransen, J., & Impellizzeri, F. M. (2022). The effect of augmented feedback on the performance and learning of gross motor and sport-specific skills: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 63, 102277. doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2022.102277

[38] Porto Maciel, L.F., Krapp do Nascimento, R., Milistetd, M., Vieira do Nascimento, J. & Folle, A. (2021) Systematic Review of Social Influences in Sport: Family, Coach and Teammate Support. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 145, 39–52. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2021/3).145.06

[39] Ronkainen, N. J., Sleeman, E., & Richardson, D. (2020). “I want to do well for myself as well!”: Constructing coaching careers in elite women’s football. Sports Coaching Review, 9(3), 321–339. doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2019.1676089

[40] Russel, J. A. (1980). A cirumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6), 1161–1178. doi.org/10.1037/h0077714

[41] Sackett, G.P. (1980). Lag sequential analysis as a data reduction technique in social . D.B. Sawin, R.C. Hawkins, L.O. Walker eta J.H. Penticuff (Eds.), Exceptional infant. Psychosocial risks in infant-environment transactions (pp. 300–340). Nueva York: Brunner/Mazel.

[42] Sánchez-Algarra, P., & Anguera, M. T. (2013). Qualitative/quantitative integration in the inductive observational study of interactive behaviour: Impact of recording and coding predominating perspectives. Quality & Quantity. International Journal of Methodology, 47(2), 1237–1257. doi.org/10.1007/s11135-012-9764-6

[43] Smith, R. E., & Smoll, F. L. (1996). The coach as a focus of research and intervention in youth sports. In F. L. Smoll & R. E. Smith (Eds.), Children and youth in sport: A Biopsychosocia Perspective (pp. 125-141). Brown and Benchmark, Inc.

[44] Sousa, C., Cruz, J., Torregrosa, M., Vilches, D., & Viladrich. C. (2006) Evaluación conductual y programa de asesoramiento personalizado a entrenadores (PAPE) de deportistas jóvenes. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 15(2), 263–278.

[45] Stirling, A. (2013). Understanding the use of emotionally abusive coaching practices. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 8(4), 625–640. doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.8.4.625

[46] Turnnidge, J. L. (2017). An exploration of coaches ’ leadership behaviours in youth sport. Queen’s University.

[47] van Kleef, G. A., Cheshin, A., Koning, L. F., & Wolf, S. A. (2019). Emotional games: How coaches’ emotional expressions shape players’ emotions, inferences, and team performance. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 41, 1–11. doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.11.004

[48] Vierimaa, M., Turnnidge, J., Evans, B., & Côté, J. (2016). Tools and techniques used in the observation of coach behaviour. In P. A. Davis (Ed.), The Psychology of Effective Coaching and Management (pp. 111–132). Nova Science Publishers.

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: X, XXX 2024

Accepted: XX, XXXXXX 2024

Published: 1, April 2025

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en