Traditional Dances and their Characteristic Injury Profiles. Systematic Review

*Corresponding author: Yaiza Taboada-Iglesias yaitaboada@uvigo.es

Cite this article

Taboada-Iglesias, Y., Abalo-Núñez, R., & García-Remeseiro, T. (2020). Traditional Dances and their Characteristic Injury Profiles. Systematic review. Apunts. Educación Física y Deportes, 141, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2020/3).141.01

Abstract

Determination of the injury profiles that characterise the sports and artistic disciplines in which the body is the medium is essential to proper injury prevention. Although many studies have been conducted in classical and contemporary dance in this regard, there is very little research and consensus documents dealing with traditional dances that establish individual and standards characteristics for all of them. For this reason, the objective of this study was to ascertain the injury profiles of dancers of different styles of traditional dancing, establishing differences and similarities between them in terms of frequency, location, type and severity and risk factors. A systematic review was performed in the Sport Discus, Medline, Cinahl, Scopus and Web of Science databases. Seventeen (17) results were obtained, representing Irish dance, flamenco, Belly dance, Indian dance, Turkish dance and Morris dance from Great Britain. The results point to a high injury incidence, albeit with differences between the styles. Injury location was also specific, although the lower extremities were particularly prevalent in all styles, except in the Belly dance, where lower back, sacral and pelvic area injuries predominated.

Introduction

Dancing has always been inherent to human development and to that of society, although its origins are somewhat vague. It is considered the foremost form of art, with references dating back to the prehistoric era. From aboriginal dances through to the introduction of dancing into the culture of peoples such as Egypt, India or Greece, dancing gradually branched out into different expressions such as hunting expeditions, births, religious holidays, through to its facet of pure entertainment (Markessinis, 1995). Art and its manifestations, such as dancing and music, have evolved parallel to the development of societies and cultures. In this way, folk dancing may be regarded as a product of a territory’s historical evolution.

Despite the broad variety of folk dances, studies related to dancing focus mainly on classical, modern or contemporary dance, addressing topics such as performance, biomechanics, didactics and health.

Movement is the cornerstone of dancing, and the medium of expression is the dancer’s body, requiring strenuous training that can lead to injury (Cardoso et al., 2017). For this reason, one of the most important health objectives is injury analysis. Abalo et al. (2013) state that producing an injury and incidence profile must be the point of departure for the proper injury prevention in sport. Moreover, the studies that have been conducted about injury incidence related to sports performance have also been complemented by work addressing the recreational sports perspective (García-González et al. 2015).

The studies performed on injuries in classical dance or ballet point to a predominant location in the lower extremities (Cardoso et al., 2017; Ekegren et al., 2014; Leanderson et al., 2011), with the most frequent cause being overuse (Ekegren et al., 2014; Leanderson et al., 2011). Similarly, modern or contemporary dance injuries are more frequently sustained to the foot and the ankle, as well as the back (Shah et al., 2012).

For the above reasons, the objective of this review was to establish the injury profiles of dancers of different styles of traditional dance, establishing differences and similarities between them in terms of frequency, location, type and severity of lesion and risk factors.

Methodology

The data collection process for this study involved a systematic review in the following databases: Sport Discus, Medline, Cinahl Scopus and Web of Science (WoS). The search was run in using the following descriptors from Medical Subjects Headings (MeSH): “WOUNDS & injuries”, “FOLK dancing” and “dancing” “Traditional dance”. To complete the search, the following keywords were included: “injuries”, “athletic injuries”, “pain”, “injury”, “injured”, “dance” and “traditional dance” (Table 1).

Table 1

Search equations in the different databases

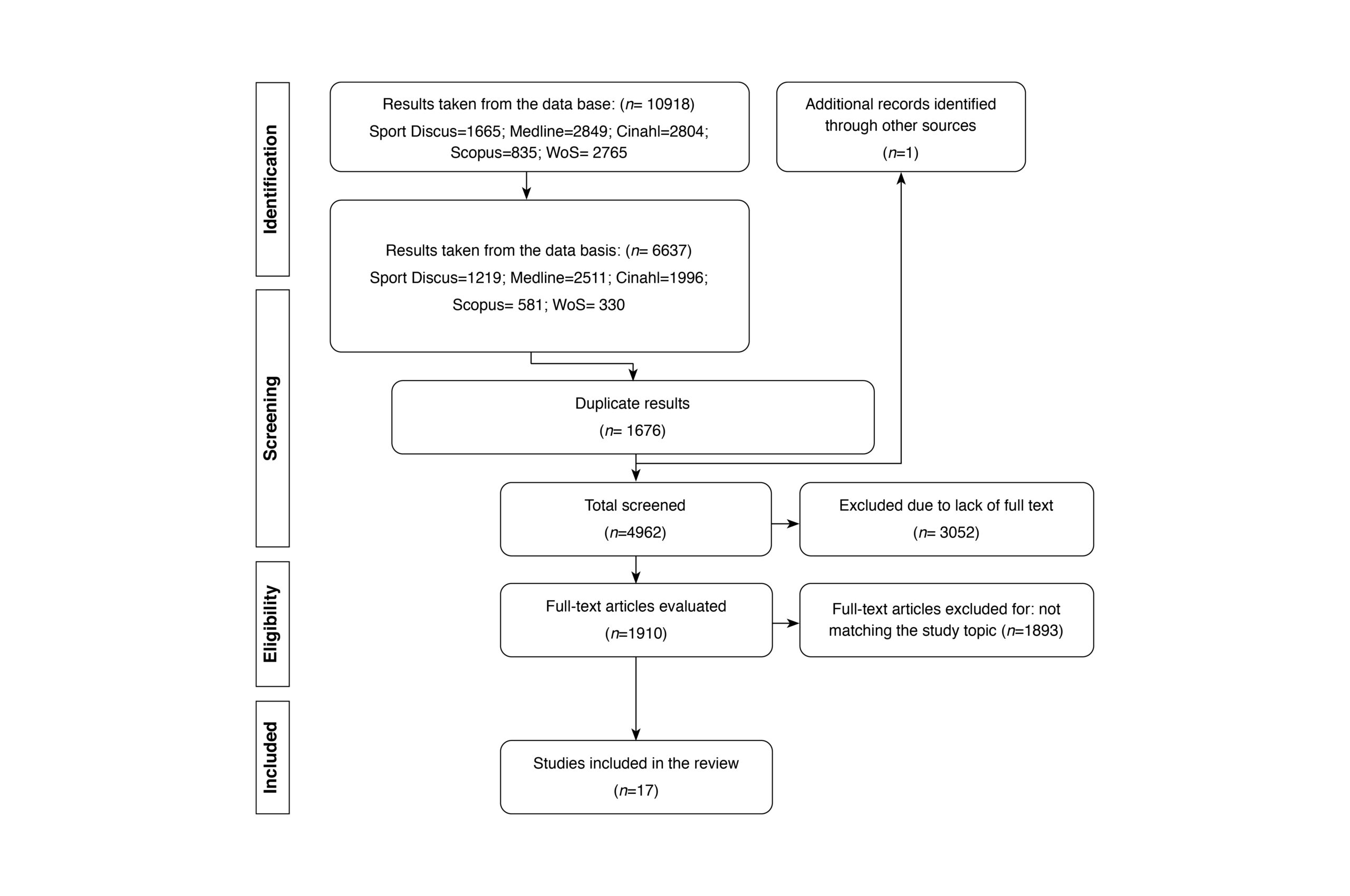

Screening criteria were applied to all the articles found. Scientific articles published in Spanish, English and French were included and were applied as search filters. Any results from which a full text was not obtained, did not match the topic of the study or were cases, case series and reviews, were excluded. There was no time limit. Moreover, in WoS the results were limited to three categories in order to yield more precise results (Sports Sciences, orthopedics, rehabilitation). (Figure 1).

Results

The characteristics of the studies are included in table 2. The dance style with the greatest body of research was Irish dance, followed by Flamenco. However, the other dances only obtain one result each. To simplify understanding, the results are grouped according to style, whereas table 3 evaluates methodological quality.

Table 2

Characteristics of the articles analysed

Table 3

Irish Dance

From the numerous studies performed in Irish dance, McGuinness and Doody (2006) analysed the dancers participating in the North American championship of this dance style. It transpired that 79% of the participants sustained at least one injury, with the ankle (31%) and the foot (25%) being the most frequent sites. Sprained ankles and stress fractures of the foot accounted for 29% and 12%, respectively. Sixty-three percent (63%) took more than 21 days to recover. They also observed a significant reduction in ankle injuries, with shoes to absorb impacts and warm-up and recovery periods used. Nevertheless, there are methodological issues with the collection of data related to injuries, clinical assessment and level of activity.

Subsequently, Noon et al. (2010) collected all the medical cases attended to in a company. The results indicated 217 injuries, and most of the dancers sustained multiple injuries, which increased with the type of dance. The injuries were mainly stress fractures (29.9%), most of them located in the sesamoid bones. Patellofemoral pain syndrome accounted for a noteworthy 11.1%. In turn, they showed that most injuries (94.9%) were sustained in the lower extremities. Although they do not take extrinsic factors into account, the results are important on account of the study’s high methodological level, since it scored 7 out of a possible 8 points.

Chronic ankle lesions were common in the study by Walls et al. (2010), since only 3 out of 18 Irish dance professionals obtained radiologically normal findings. The most frequent conditions were Achilles tendonites (n: 14). Nevertheless, 8 of the participants had no ankle pain, and despite the good methodological quality, they lack variables that analyse the intrinsic and extrinsic factors.

Cahalan and O’Sullivan (2013) focused on injury ratio and risk factors. They collected a total of 396 lesions, although the main methodological problem was the failure to perform in situ data collection, not provide a memory bias, thus rendering the clinical assessment deficient. They found that 76.7% of the dancers had sustained a previous injury, mainly to the foot (67.9%) and the ankle (60.6%), as well as a ratio of 2.25 injuries per dancer in the course of their career. Although the severity of most of the injuries was rated as minor, more frequently in the foot and ankle, 33.7% of the dancers did admit that dancing was often or always painful. They also established the risk factors that most perceptively contribute to injury, namely accidents, fatigue or overuse, repeat movements or an unstable stage.

In the same year, Stein et al. (2013) published a study with a high methodological quality (7 points) in which, of 437 diagnosed injuries, 80% were due to overuse and 20.4% were trauma-induced. Fifty-eight percent (58%) of the dancers had one injury, whereas 23.9% had two and 18% three or more diagnoses. Ninety-five percent (95%) of these injuries were located in the hips and lower extremities (33.2% foot, 22.7% ankle, 19.7% knee and 14.4% hip). The most common type of injury were tendonites (13.3%), followed by apoptosis (11.4%), pain and patellofemoral instability (10.8%), stress fractures (10.1%) and muscular injuries (7.8%). However, the fact that they did not analyse the level of practice must be considered.

Cahalan et al. (2015) observed that 31.7% of Irish dancers sustained significant injuries, which was associated with being female, having a high perception of health problems and psychological, mood, catastrophic problems and failing to do warm-up exercises consistently. They highlighted the foot and the ankle as the most commonly injured areas (48.8%). However, most of the specific diagnoses were pulled muscles (17.2%).

In another study, of all the lesions, 55.8% were located in the foot and ankle and 63.1% of the dancers sustained injuries in this area. It also transpired that the reasons perceived by the dancers are overuse or fatigue (32.5%), accidents (15.6%), previous injuries (13.2%) poor warm-up or stretching (11.3%) and other biomechanical factors (11.3%) (Cahalan et al., 2016).

The article by Cahalan et al. (2017) analyses the biopsychosocial factors associated with foot and ankle injuries, comparing them between Irish dancers who had sustained an injury to that area to those who had not. The results showed that foot and ankle injuries were related to the failure to do a consistent warm-up, have low energy levels and other pains or complaints. Dancers with foot or ankle lesions perceive the greatest risks as being overuse (17.6%) and previous lesions (16.9%).

Cahalan, Bargary and O’Sullivan (2018) established that 84% of elite adolescent dancers had at least one pain episode or injury in 12 months, the most affected areas being the foot and the ankle. Having complaints in parts of the body, pain often or always while they dance and feelings of anger or hostility were regarded as factors significantly associated with injury.

Another study by Cahalan, Kearney, Bhriain et al. (2018) established that pre-professional Irish dancers have an injury incidence of some 10.6 injuries per 1000 hours of exposure. They collected a total of 88 injuries, a mean (SD) of 4.2 (2.5) injuries per dancer which prevented them from dancing, either partially or fully, for a mean period of 10 days. The lower extremities (particularly the foot and ankle, with 23.9%) and the base of the spine were the most frequently injured areas. 57.5% of the injuries did not have a clear diagnosis, and those that did were mostly muscle injuries. Similarly, the main specific cause of injury was overuse. Finally, lack of sleep, general health or increased hours of exercise were associated with injuries.

The main methodological problems in the publications by Cahalan et al. are the failure to record the injury when it occurs, the failure to prevent memory bias and the lack of a suitable clinical assessment. However, the studies by Cahalan, Kearney, Bhriain et al. (2018), Cahalan et al. (2016) and Cahalan et al. (2016) provide a strategy for limiting memory bias by requesting weekly or monthly incidence recording.

Flamenco

Bejjani et al. (1988) found a high incidence of urogenital disorders (50%), one of the dangers of exposure to percussive footwork-derived vibration, in professional dancers from New York. The following areas with the highest incidence were back (28.6%) and head and neck pain (26.8%). Moreover, pain in the extremities was lower than in the other areas. Nevertheless, they did not define the injury nor evaluate intrinsic or extrinsic factors and also presented a poor data analysis.

Castillo-López and Vargas-Macías (2014) analysed pain and hyperkeratosis in the metatarsal area in Andalusian professional dancers. 80.7% of the dancers reported metatarsal pain while dancing flamenco and 84.1% plantar hyperkeratosis with a greater incidence in the heads of the first and second metatarsals. However, they failed to establish a direct significant relationship between both variables and neither did they detect a relationship between pain and shoe heel height.

In the same line, Castillo-López (2016), with a better methodological description than the previous article, found that most professional dancers in this dance style exhibit foot problems. Deformities appear in 76.8% of the cases, 95% have metatarsal pain and 82% plantar hyperkeratosis.

Belly Dance

The Belly dance study was performed by Milner et al. (2019), on a community of dancers of this style from New Zealand, and it shares certain methodological limitations with the other results: they did not record the results as they occurred, there was no data omission strategy and no exhaustive clinical assessment. They collected 40 injuries in the preceding 12 months, establishing an injury ratio of 37% (40 lesions in 109 dancers). Most of the injuries (38%) were located in the spinal, sacral and pelvic areas. Nevertheless, the only variable that predicted injury location was dancer experience, and the most experienced dancers have a greater likelihood of sustaining injury to the lower extremities.

Indian Dance

With regard to the publications on Indians Dance, Nair et al. (2018) indicated that in the different dance styles the distribution of pain among dancers was mainly in the back, followed by the ankles and knees, although the Bharatanatyam and traditional dance styles presented specificities. Moreover, they showed that they do not sustain injuries to the hips, thighs, hands or wrists. It also presented the same methodological limitations as the previous study.

Turkish/Anatolian Dance

Aksu et al. (2018) examined the injuries sustained by the dancers of a professional Anatolian dance company that required surgery; they reported 14 orthopaedic lesions in 18.6% of the dancers, with a prevalence 8.64 times higher in men than in women. Of these, 64% were caused by traumatic injuries and 35.7% by chronic conditions. 85.7% of the injuries were sustained in the lower extremities, all of them in knees affected by impacts and repeat jump reception over long periods of time. All the injuries to the lower extremities occurred during performances, whereas hand or wrist injuries were sustained in rehearsals. Age was not a significant predictive variable of injury.

Certain dance figures or technical executions presented specific injuries. Meniscus injuries occurred after frequent sit-ups and pirouettes in dances and torn anterior cruciate ligament lesions occur after jumps and jump receptions. It should be mentioned that despite a good data collection methodology they failed to provide intrinsic and extrinsic factors and the data analysis should have been more exhaustive.

Morris Dance

Finally, the study by Tuffery (1989) analyses the injuries in Morris dance, a traditional dance in Great Britain, with very low methodological quality. The research showed that 59% of traumatic injuries are sustained by women, although they are not directly age-related. Nevertheless, there was a significant greater incidence of chronic injuries in older dancers.

Seventy percent (70%) of trauma injuries occur in the lower extremities, particularly in the calf and in the ankle, most of the latter involving sprains. It was associated with the dancing surface in 39% of the cases. Similarly, in the relationship between genders, only toe and knee injuries proved to be significantly different, with men sustaining more injuries. Twenty-four percent (24%) of the injuries were classified as mild, 33% as moderate and 43% as severe.

Of the 47 chronic injuries reported, only 11% occurred in women and they were significantly lower than trauma-induced injuries; moreover, significant differences were also found between sexes, with men sustaining more chronic injuries. The main location was the knee.

Discussion

The analysis of the results makes it possible to establish certain similarities and differences between the different traditional dance styles from all over the world. One of the main problems in the studies performed to date is that most of them are retrospective (Aksu et al., 2018; Cahalan, Bargary & O`Sullivan 2018; Cahalan et al., 2015; Cahalan & O´Sullivan 2013; McGuinness & Doody 2006; Milner et al., 2019; Nair et al., 2018; Noon et al., 2010; Stein et al., 2013; Tuffery 1989), with the related drawbacks in terms of loss of information. Only 3 of the 17 results were prospective (Cahalan et al., 2016; Cahalan et al., 2017; Cahalan, Kearney, Bhriain et al., 2018). All the articles presented samples from both sexes, except those by Milner et al. (2019) conducted in Belly dance, those by Beijani et al. (1988), Castillo-López and Vargas-Macías (2014) and Castillo-López (2016) in Flamenco, and the study by Noon et al. (2010) in Irish dance, which only analysed results in women. Moreover, most of the dancers were top-level, and are referred to as professionals, pre-professionals, elite or full-time dance students. Only the study by Tuffery (1989) in Morris dance, that of Milner et al. (2019) in Belly dance and the study by Nair et al. (2018) in Indian dance included amateur dancers.

With regard to the methodological quality of the documents included in this research, of the 17 articles, all of them, except for the one focusing on Morris dance (3 points) merited a score of four or more points, although by disciplines (Belly, Indian or Turkish dance) only one article with a score of 5 was found .

Injury incidence

Injuries and pain in the different types of dancing appear to be constant. Approximately 80% of Irish dance (McGuinness & Doody, 2006; Cahalan, Bargary & O’Sullivan, 2018) and Flamenco dancers (Castillo-López & Vargas-Macías, 2014; Castillo-López, 2016) sustained some type of injury or pain. Despite this, Stein et al. (2013) establish lower percentages in Irish dance, although the level of the dancers is not mentioned, which could affect the results, although this study enjoys greater relevance in terms of methodological quality. In turn, less than half of the Irish dancers sustain injuries when defined as significant (Cahalan et al., 2015). These lower injury ratios are more similar to the ones found in Belly dance (Milner et al., 2019).

On the other hand, most of the Irish dancers presented multiple injuries (Noon et al., 2010). The prospective study by Cahalan, Kearney, Bhriain et al., (2018) reported a mean incidence of 4 injuries per dancer; however, Cahalan and O’Sullivan (2013) indicated that in the course of their career dancers sustain a ratio of 2 injuries, although the study may be biased by the fact that it is retrospective and its methodological quality is below that of the previous one.

Location

A substantial number of injuries are located in the lower extremities in practically all dance styles. Most of the lesions in Irish dance (Noon et al., 2010) that require surgery in Turkish dance (Aksu et al., 2018) and in Morris dance (Tuffery, 1989) are related to each other, albeit with specific characteristics, since the knee is predominant in Turkish dance (Aksu et al., 2018) and the calf and ankle are more prevalent in Morris dance (Tuffery, 1989).

The ankle and the foot are the most frequent locations in Irish dance (Cahalan & O’Sullivan, 2013; Cahalan et al. 2015; Cahalan et al. 2016; Cahalan, Bargary & O`Sullivan, 2018; Cahalan, Kearney, Bhriain et al., 2018; McGuinness & Doody, 2006; Noon et al., 2010; Stein et al., 2013), and while most Flamenco dancers experience metatarsal pain and foot issues (Castillo-López & Vargas-Macías, 2014; Castillo-López, 2016), Bejjani et al. (1988), the researchers found a predominant incidence of urogenital problems derived from exposure to percussive footwork vibration, with the back, head and neck being the worst-hit areas.

In Indian dance, ankle and knee lesions take second place to the more frequent back injuries (Nair et al., 2018). Similarly, in Belly dance, the areas with greatest incidence were the lower back, sacral and pelvic areas, and the more experienced dancers were more likely to sustain injuries to the lower extremities (Milner et al., 2019). These articles received an average score in comparison with the studies performed in other styles.

Type of injury

With regard to type of injury, there is not too much consensus in Irish dance, since while all the studies report almost the same types, different researchers attach different priority to them. Moreover, McGuiness and Doody (2006) place sprained ankles as the most frequent type, followed by stress fractures of the feet. Nevertheless, the latter, and with greater incidence in the sesamoid bones, are the most frequent type in the studies by Noon et al. (2010), which features greater methodological quality, and placing patellofemoral syndrome second. With the same methodological quality, pain and patellofemoral instability, followed by stress fractures, are the second and third most frequent types in the studies by Stein et al., (2013), who identify tendinitis injuries as the most common type of chronic injuries, as do Walls et al. (2010). For Cahalan et al. (2015), the significant injuries with a clear diagnosis were pulled muscles.

Moreover, in Morris dance, as in the Irish dance studies by McGuiness and Doody (2006), most of the injuries are sprained ankles.

Severity

Injury severity is usually established in relation to the time during which the subject is prevented from performing. In this case, McGuiness and Doody (2006) observed that most of the injuries obliged Irish dancers to observe a recovery period of 21 days, meaning that the injuries were classified as serious. Most of the trauma injuries in Morris dance are largely classified as severe (Tuffery, 1989). Nevertheless, in Irish dance, Cahalan and O’Sullivan (2013), with greater methodological quality, established that most of the injuries are of minor severity, although a significant percentage of dancers admit that they always dance in pain. This idea of coping with pain may be concluded on the basis of the results obtained by Castillo-López and Vargas-Macías, (2014), who state that the high percentage of bailaoras (Flamenco dancers) suffer metatarsal pain while dancing. Thus, these injuries, regarded as minor, are highly important since they prevent the dancers from dancing in fully-fit conditions.

Risk factors

Most of the injuries that occur in Irish dance are caused by overuse, whereas the percentage of trauma injuries is lower (Stein et al., 2013). Fatigue or overuse and repeat movements are established risk factors perceived by these dancers (Cahalan & O´Sullivan, 2013; Cahalan et al., 2016; Cahalan et al., 2017), although so too are accidents. Chronic injuries therefore take on major importance (Walls et al., 2010). This is similar to the urogenital injuries in Flamenco dance caused by percussive footwork vibration reported by Bejjani et al. (1988).

The use of shoes to dampen impacts significantly reduces injuries in Irish dance (McGuinness & Doody, 2006), as does a proper warm-up and recovery period. However, Castillo-López and Vargas-Macías (2014) did not find a direct significant relationship between shoe heel height and pain. Warming up was also established as a factor associated with injuries in other studies (Cahalan et al., 2015; Cahalan et al., 2016; Cahalan et al., 2017), among other risk factors, such as being a woman and other health problems.

Conclusions

Traditional dancers present a high incidence of injuries, with differences between dance styles. Belly dance induces lower injury ratios compared to the incidence of significant injuries in Irish dance.

The location of these injuries is specific to dance style. Nevertheless, the lower extremities enjoy particular relevance in all of them, except in the Belly dance, in which the incidence is greater in the lumbar, sacral and pelvic areas. The most affected parts, according to dance type, are: in Irish dance, the knee; In Morris dance, the calf and ankle; in flamenco, urogenital problems, and in Indian dance, the back.

Similarly, and while there is no consensus on injury severity, many dancers admitted that they regularly dance in pain in the Irish and Flamenco styles.

Limitations and future prospects

Despite the extensive variety of traditional dances, studies have not been performed in all of them, whereby it proved impossible to establish the profiles or to study the differences and similarities properly. Another limitation of this work was that most of the studies were retrospective, with the subsequent possible loss of information.

Due to the specificity of each dance, a greater number of studies would be necessary in the specific dances that have yet to be addressed, and the results of the dances studied would need to be expanded. It would also be important to have prospective studies that afford a more objective vision of reality.

References

[1] Abalo Núñez, R., Gutiérrez-Sánchez, Á., & Vernetta Santana, M. (2013). Analysis of incidence of injury in Spanish elite in aerobic gymnastics. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte, 19(5):355-8. doi.org/10.1590/S1517-86922013000500011

[2] Aksu, N., Atansay, V., Aksu, T., Koçulu, S., Damla Kara, S., & Karalök, I. (2018). Injuries Requiring Surgery in Folk Dancers: A Retrospective Cohort Study of 9 Years. Journal of Sports Science, 6, 108-117. doi.org/10.17265/2332-7839/2018.02.006.

[3] Bejjani, F.J., Halpern, N., Pio, A., Dominguez, R., Voloshin, A., & Frankel, V.H. (1988). Musculoskeletal demands on flamenco dancers: A clinical and biomechanical study. Foot & Ankle, 8(5), 254-263. doi.org/10.1177/107110078800800505

[4] Cahalan, R., Bargary, N., & O`Sullivan, K. (2018). Pain and Injury in Elite Adolescent Irish Dancers. A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 22(2), 91-99. doi.org/10.12678/1089-313X.22.2.91.

[5] Cahalan, R., Kearney, P., Bhriain, O.N., Redding, E., Quin, E., McLaughlin, L.C., & O`Sullivan, K. (2018). Dance exposure, wellbeing and injury in collegiate Irish and contemporary dancers: A prospective study. Physical Therapy in Sport, 34, 77-83. doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2018.09.006

[6] Cahalan, R., O’Sullivan, P., Purtill, H., Bargary, N., Ni Bhriain, O., & O’Sullivan, K. (2016). Inability to perform because of pain/injury in elite adult Irish dance: A prospective investigation of contributing factors. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 26,694-702. doi.org/10.1111/sms.12492

[7] Cahalan, R. & O’Sullivan, K. (2013). Injury in Professional Irish Dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 17(4),150-158. doi.org/10.12678/1089-313X.17.4.150

[8] Cahalan, R., Purtill, H., & O’Sullivan, K. (2015). A Cross-Sectional Study of Elite Adult Irish Dancers Biopsychosocial Traits, Pain, and Injury. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 19(1), 31-43. doi.org/10.12678/1089-313X.19.1.31

[9] Cahalan, R., Purtill, H., & O’Sullivan, K. (2017). Biopsychosocial Factors Associated with Foot and Ankle Pain and Injury in Irish Dance. A Prospective Study. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 32(2), 111-117. doi.org/10.21091/mppa.2017.2018

[10] Cardoso, A.A., Reis, N.M., Marinho, A.P.R., Vieira, M.C.S, Boing, L, & Guimarães, A.C.A. (2017). Injuries in professional dancers: a systematic review. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte, 23(6), 504-509. doi.org/10.1590/1517-869220172306170788.

[11] Castillo-López, J.M. (2016). Resultados y prospectiva de la investigación podológica en el baile flamenco. Revista del Centro de Investigación Flamenco Telethusa, 9(11), 18-22. doi.org/10.23754/telethusa.091104.2016

[12] Castillo-López, J.M, & Vargas-Macías, A., Domínguez-Maldonado, G., Lafuente-Sotillos, G., Ramos-Ortega, J., Palomo-Toucedo, I.C., Reina-Bueno, M., Munuera-Martínez, P.V. (2014). Metatarsal Pain and Plantar Hyperkeratosis in the Forefeet of Female Professional Flamenco Dancers. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 29(4),193-197.

[13] Ekegren, C.L., Quested, R., & Brodrick, A. (2014). Injuries in pre-professional ballet dancers: Incidence, characteristics and consequences. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 17(3), 271-5. doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2013.07.013.

[14] García González, C., Albaladejo Vicente, R., Villanueva Orbáiz, R., & Navarro Cabello, E. (2015). Epidemiological Study of Sports Injuries and their Consequences in Recreational Sport in Spain. Apunts. Educación Física y Deportes, 119, 62-70. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2015/1).119.03

[15] Leanderson, C., Leanderson, J., Wykman, A., Strender, L.E., Johansson, S.E., & Sundquist, K. (2011). Musculoskeletal injuries in young ballet dancers. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 19(9), 1531-5. doi.org/10.1007/s00167-011-1445-9

[16] Markessinis, A. (1995). Historia de la danza desde sus orígenes. Madrid: Lib. Deportivas Esteban Sanz.

[17] McGuinness, D., & Doody, C. (2006). The injuries of competitive Irish dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 10(1-2), 35-39.

[18] Milner, S.C., BCom, A.G., & Bussey, M. (2019). A Retrospective Study Investigating Injury Incidence and Factors Associated with Injury Among Belly Dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 23(1), 26-33. doi.org/10.12678/1089-313X.23.1.26

[19] Nair, S.P., Kotian, S., Hiller, C., & Mullerpatan, R. (2018). Survey of Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Indian Dancers in Mumbai and Mangalore. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 22(2), 67-74. doi.org/10.12678/1089-313X.22.2.67

[20] Noon, M., Hoch, A.Z., McNamara, L., & Schimke, J. (2010). Injury patterns in female irish dancers. PM & R: the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation, 2(11), 1030-4 doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.05.013

[21] Shah, S., Weiss, D.S., & Burchette, R.J. (2012). Injuries in Professional Modern Dancers: lncidence, Risk Factors, and Management. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 16(1), 17-25.

[22] Stein, C.J., Tyson, K.D., Johnson, V.M., Popoli, D.M., d’Hemecourt, P.A., & Micheli, L.J. (2013). Injuries in Irish Dance. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 17(4), 159-164. doi.org/10.12678/1089-313X.17.4.159

[23] Tuffery, A.R. (1989). The nature and incidence of injuries in Morris dancers. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 23(3), 155-160. doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.23.3.155

[24] Walls R.J., Brennan S.A., Hodnett P., O’Byrne J.M., Eustace S.J., & Stephens M.M. (2010). Overuse ankle injuries in professional Irish dancers. Foot and Ankle Surgery, 16, 45-49. doi.org/10.1016/j.fas.2009.05.003

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: 17 Desember 2019

Accepted: 01 April 2020

Published: 01 July 2020

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en