The Hybridization of Pedagogical Models to Enhance Personal Responsibility in the Improvement of Physical Fitness in Adolescents

*Corresponding author: Marc Ferrer mferr113@xtec.cat

Cite this article

Ferrer, M., Camerino, O., & Castañer, M. (2025). The hybridization of pedagogical models to enhance personal responsibility in the improvement of physical fitness in adolescents. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 162, 19-30. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2025/4).162.03

Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine the results in physical education of the year-long hybridization of the Personal and Social Responsibility Model, combined with four other pedagogical models—attitudinal style, cooperative learning, sport education, and health-based physical education—according to gender. The study analyzed the effects on students’ motivation, intention to be physically active, satisfaction of basic psychological needs, and personal and social responsibility in secondary school students. A mixed-methods methodological design was used with a sample of 92 students (43 girls and 49 boys), divided into an experimental and a control group, aged between 11 and 13 years (M = 12.24; SD = 0.32). The instruments applied were the BREQ-3, IPA, BPNSE, and PSRQ questionnaires, along with a physical fitness test to assess the influence of hybridization. A repeated-measures multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted on the different variables according to time (pre-post), group (control and experimental), and sex, with a significance level set at p < .05. Significant results were found in relation to gender as female students in the experimental group showed improvements in all physical fitness tests, in controlled motivation, and in the intention to be physically active. Improvements were also observed in autonomy and responsibility in the entire experimental group, although these could not be supported by the PSRQ questionnaire. It is suggested that physical education teachers implement the hybridization of pedagogical models to meet the current needs of the teaching-learning process, in order to achieve meaningful and high-quality physical education.

Introduction

Currently, one of the issues that arise during adolescence, between the ages of 11 and 17, is the high prevalence of insufficient physical activity (PA). In Spain, 76.6% of adolescents do not meet the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) requirement of engaging in at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous PA per day, despite the physical, psychological, and social benefits it provides (Barbosa-Granados and Urrea-Cuéllar, 2018; Ludick, 2018).

To reverse this situation, the WHO launched a Global Action Plan on Physical Activity (2019) aimed at achieving a relative 15% reduction in the prevalence of insufficient PA among children, adolescents, and adults. However, in order to be more effective when implementing an intervention, it is necessary to know and understand the factors that influence PA practice (Baena-Extremera et al., 2014). In other words, for an intervention to be effective, it must have an impact on multiple levels, since health is a complex concept involving multiple interconnected dimensions.

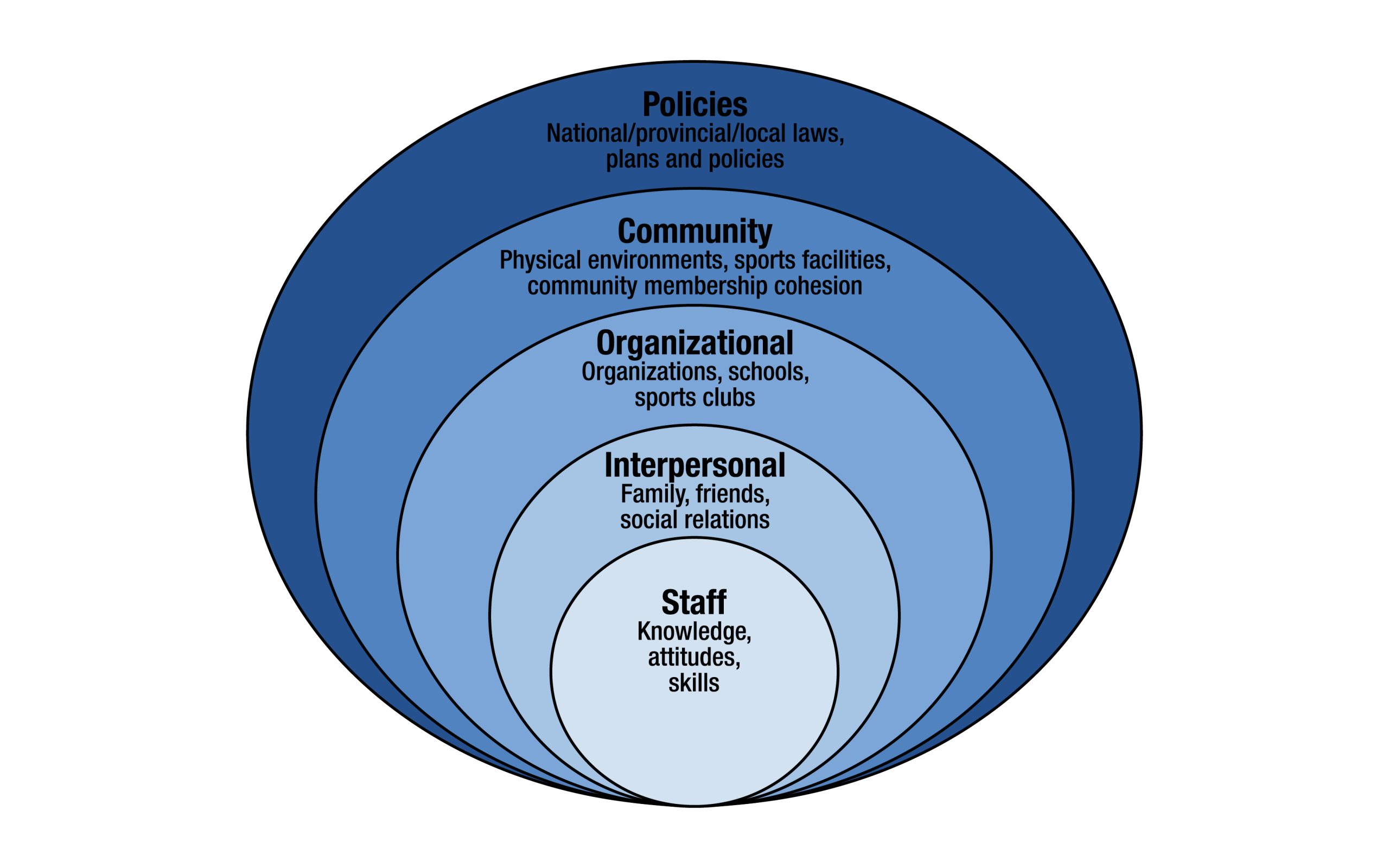

One of the approaches that addresses the interaction of different factors and levels is the socioecological model (McLeroy et al., 1988). This model suggests that health is not only the result of individual factors but also of social and environmental interactions. It is made up of five levels (Figure 1): personal (knowledge, attitudes, and skills); interpersonal (family, friends, school relationships); organizational (associations, sports federations, and cohesion with community members); community (physical environments, sports facilities); and public policies (laws, regulations, and plans at the state, regional, or local level).

Sicilia and Delgado (2002) highlight the need for the various stakeholders involved in the individual’s overall development, such as the school, family, administration, or advertising, to work in a coordinated way. The educational field, and more specifically physical education (PE), has great potential to promote PA among young people, both directly—through the accumulation of PA minutes or positive experiences—and indirectly—by fostering the acquisition of a physically active lifestyle— (Slingerland & Borghouts, 2011). As a result, there is a push for exposure to quality PE, which stresses the importance of: “… equipping all children and young people with the competencies, aptitudes, attitudes, values, knowledge, and understanding needed for lifelong participation in society.” (McLennan & Thompson, 2015, p. 6). As part of this new orientation, the term Meaningful Physical Education (MPE) has emerged, aiming to focus on how students perceive the subject and how to ensure this perception has a positive meaning in their lives (Fernández-Río & Saiz-González, 2023).

MPE and quality PE, together with the socioecological model, can help us create more effective, meaningful, and relevant PE programs for students, thus adapting the PE curriculum accordingly.

To create these programs, the use of pedagogical models (PM) is proposed. These are defined as: “Long-term approaches, complete extended learning situations (LS), which provide a comprehensive and coherent teaching plan to achieve specific learning objectives through plans, decisions, and actions consistent with a context and content” (Fernández-Río et al., 2021, p. 17). The main pedagogical models can be grouped into: a) basic models, such as cooperative learning, the Sport Education Model (SEM), the Teaching Games for Understanding model (TGfU), and the Personal and Social Responsibility Model (TPSR); and b) emerging models such as adventure education, motor literacy, the attitudinal style, the play-based technical model, the self-construction of materials, and health-related PE (Fernández-Río et al., 2016).

However, Pérez-Pueyo et al. (2021) argue that there is no single teaching model that applies to all knowledge or educational contexts, and therefore it is necessary to extract the most significant elements of each model and interrelate them, giving rise to an educational possibility with great potential. The use of different models jointly implies hybridizing them. The aim of hybridization is to find ways to adjust the teaching process to achieve the most appropriate and coherent learning for students. Meta-analyses on the hybridization of pedagogical models (González-Víllora et al., 2018; Shen & Shao, 2022) have shown improvements in physical and cognitive domains, sports technical skills, motivation, autonomy, as well as personal and responsibility skills.

With regard to gender, it has been observed that during adolescence sedentary behavior and sports dropout increase in females (Ribero et al., 2024). Studies have found that intrinsic motivation is more closely related to girls, while extrinsic motivation is more related to boys (Moral-García et al., 2019). In terms of perceived competency, girls assess their competency through internal and social sources, whereas boys do so in relation to competitive results and the ease of learning new skills (Murillo et al., 2014). On the other hand, several studies show higher levels of responsibility in boys compared to girls (Sánchez-Alcaraz et al., 2021), although there are studies that show the opposite Gómez-Mármol et al., 2017).

The main objective of the present study was to examine the effects of hybridizing the TPSR (Hellison, 2011) in PE with other PMs—cooperative learning, health-related PE, attitudinal style, and SEM—compared to traditional methodology, according to gender, on students’ motivation, intention to be physically active, satisfaction of basic psychological needs, and personal and social responsibility.

Methodology

Study Design and Approach

The study follows an action-research approach by implementing, throughout an academic year program (September to June), the hybridization of the TPSR with other pedagogical models such as the attitudinal style, cooperative learning, SEM, and health-related PE.

The methodology design applied was embedded mixed methods (Anguera et al., 2012), with multilevel triangulation indicating the two levels of data analyzed, derived from the quantitative and qualitative results of the different instruments used and later combined. The design was quasi-experimental, using pre-test and post-test measurements (Pérez-Juste et al., 2012).

Participants

The participant sample was intentional, selecting a standard public school in Catalonia, from a town near Barcelona, with a medium-low socioeconomic level. The total number of participants in this research was 92 secondary school students aged between 11 and 13 years (M = 12.24; SD = 0.32), consisting of 43 girls and 49 boys. They were distributed into five class groups, of which three belonged to the experimental group (28 girls and 32 boys), and the other two belonged to the control group (15 girls and 17 boys).

Instruments

Following the embedded mixed methods design, the instruments employed before and after the intervention (Table 1) can be divided into two groups of different nature: those that provided qualitative data, based on the recording and viewing of the sessions to evaluate teacher performance, group progress, and the writing of a researcher’s diary on the intervention; and those that provided quantitative data obtained through questionnaires and physical fitness tests.

The observational records are not presented in this preliminary article, but it is important to highlight the attempt at triangulation throughout the process.

Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire (BREQ-3): Instrument developed by González-Cutre et al. (2010) that measures the different types of motivation expressed in Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000). It consists of 23 items introduced with the stem: “I exercise because…” in a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (totally true). The items are grouped into intrinsic regulation, identified regulation, introjected regulation, external regulation, and amotivation.

Intention to be Physically Active (IPA): The version used was developed by Moreno et al. (2007), adapted for secondary school students. The questionnaire includes five items on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), starting with “In my classes…”.

Basic Psychological Needs in Physical Education Scale (BPNSE) (Moreno et al., 2008): It consists of 12 items grouped into three factors: autonomy, competency, and relatedness. The stem is “In my classes…”, and responses are rated on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Personal and Social Responsibility Questionnaire (PSRQ) (Escartí et al., 2011): It consists of 14 items distributed across two factors: social responsibility and personal responsibility. Responses are presented on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

Physical fitness test

In addition to the questionnaires, both at the beginning and the end of the intervention, a series of physical fitness tests were administered, included within the Eurofit battery (Conseil de l’Europe, 1983) and ALPHA-Fitness (Ruiz et al., 2011). The four fitness tests carried out were:

Sit and reach: From a seated position on the floor with legs extended and feet at 90º flexion placed against a box, participants were asked to slowly and progressively bend forward as far as possible with legs and arms extended. The final position had to be held for 2 seconds.

Medicine ball throw: This test consists of throwing the medicine ball as far as possible with both arms simultaneously, without moving the feet off the ground. The main objective is to assess explosive strength of the trunk extensors, upper limbs, and lower limbs.

Standing broad jump: This test measures musculoskeletal fitness (Ruiz et al., 2011). The participant stands with feet slightly apart behind the starting line. By flexing the legs and swinging the arms backward, they generate momentum, then perform a rapid extension of the legs while swinging the arms forward. Upon landing, participants must maintain their feet in the same spot where first contact was made, without losing balance.

Shuttle run: Designed to measure maximal aerobic power. Students run back and forth between two lines set 20 meters apart, changing direction at the pace indicated by an auditory signal, which gradually accelerates. The test ends when a student fails to reach the line in time for the second consecutive beep.

Qualitative data

Along with the questionnaires and physical fitness tests, the sessions conducted during the intervention were recorded and reviewed to evaluate the implementation of the hybridization of the TPSR model with the other four pedagogical models, as well as the progression of the different groups in relation to the responsibility levels.

TARE (Escartí et al., 2015):A rubric in which, at 3-minute intervals, the degree of implementation of each TPSR strategy is assessed. The strategies include: 1) modeling respect; 2) setting expectations; 3) providing opportunities for success; 4) fostering social interaction; 5) assigning tasks; 6) promoting leadership; 7) offering choice and voice; 8) involving students in assessment; 9) promoting transfer. Based on these recordings, the researcher’s diary was written, documenting the evolution of each experimental group as well as the teacher’s role.

Procedure

The implementation of the hybridization of TPSR with the four other pedagogical models mentioned above was carried out throughout a full school year, from September to June. The researcher contacted the school during the previous academic year to explain the objectives of the study and request their participation. In addition, all participants signed informed consent, either agreeing or declining, following the ethical guidelines of the American Psychological Association regarding consent, confidentiality, and anonymity of responses. Approval had been granted by the Research Ethics Committee (022/CEICGC/2022).

Students completed the questionnaires at the beginning and at the end of the intervention using an online form via Google Forms. The lead researcher was present to clarify any questions. The physical fitness tests were administered at the beginning and end during two physical education classes, in which each student performed three attempts, with the best performance recorded, except for the shuttle run, which was performed only once. Each test lasted approximately 20 minutes.

Following the initial tests, the intervention was carried out through the implementation of the different LS planned for each term. Teacher training included a detailed explanation of TPSR, its essential components (levels of responsibility, session structure, steps for implementation), and practical strategies. For the application of the hybridization of the TPSR, the sessions of the experimental group were recorded. The teacher met weekly with collaborating researchers to review the sessions using TARE (Escartí et al., 2015), evaluate TPSR implementation, and receive suggestions to improve subsequent lessons.

Both experimental and control groups followed the same curricular content and competencies, including traditional and popular games, colpbol, aerobic endurance, acrosport, striking and fielding & racket sports and challenge-based sports. However, the difference between the two groups was related to the methodology used during the classes. The experimental group followed the hybridization of TPSR with other pedagogical models, while the control group followed a traditional approach.

The classes were structured around the methodological pillars of TPSR (integration, shared responsibility, teacher-student relationship, and transfer) and its basic structure (awareness, responsibility in action, group meeting, assessment, and self-assessment) (Hellison, 2011). To these, elements of the pedagogical model being hybridized were added. The control group followed a traditional session structure (warm-up, main part, cool down), in which the teacher led the class and students had little involvement in decision-making. In Table 2, the main characteristics of each LS implemented during the intervention are detailed.

In the last weeks of the course, the final questionnaires were passed, physical condition tests were carried out to know the evolution generated by the intervention in the students and a group discussion was held with questions related to the implementation of the TPSR in the classroom.

Statistical Analysis

The IBM SPSS 30.0.0 statistical program was used for the analysis of the variables. Descriptive statistics were obtained for all the dimensions under study; outliers were identified using the Mahalanobis distance and internal consistency was evaluated with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The great majority of the coefficients exceeded the reliability values of .70 that are considered acceptable, as in the IPA and BPNSE questionnaires. With regard to the BREQ-3 and the PSRQ, most factors exceeded reliability values of .70, while identified motivation and amotivation in the BREQ-3, and the social factor of the PSRQ were between .60 and .70, also considered acceptable according to Hu and Bentler (1999). To determine the effect of implementation, a repeated measures multivariate analysis (MANOVA) was performed on the different variables according to time (pre-post), group (control and experimental) and sex. The sex variable was taken into account as a variable that could influence the participants’ responses. A significance level of p < .05 was established.

The following formula was used to calculate the self-determination index (SDI) (Vallerand, 1997): [(2* Reg. Intrinsic) + Reg. Identified + Reg. Integrated] – [(Reg. External + Reg. Introjected ) / 2] – (2* Amotivation). Autonomous and controlling motivation were calculated using the following formulas: 1) autonomous motivation: intrinsic regulation + identified regulation; 2) controlling motivation: amotivation + external regulation + introjected regulation.

Results

The results were divided into two tables (Table 3 and Table 4); Table 3 shows the results of the physical fitness tests that were carried out; while Table 4 reflects the results obtained in the questionnaires. Both tables show the measures of the differences between the pre- and post-test, according to group and sex. Statistical significance values (p value) obtained when comparing these estimated measures (using the Bonferroni correction) are also included.

Table 3

Differences between pre-test and post-test according to sex and group (physical fitness test)

Table 4

Differences between pre-test and post-test according to sex and group (questionnaires)

If we focus on the significant differences in relation to sex, in the girls, the group that received the MP hybridization obtained higher values at the end of the intervention in the sit and reach (p = .001), in the medicine ball throw (p = .001), in the standing broad jump (p = .007) and in the shuttle run (p =.002). On the other hand, the girls in the control group showed significant improvements in medicine ball throwing (p = .001) and in the standing broad jump (p = .018). The results for the boys were different. Significant changes were obtained in medicine ball throwing (p = .016), in the standing broad jump (p = .016) and in the shuttle run (p = .001) in the experimental group; while, in the control group, significant changes were obtained in the medicine ball throw (p = .002) and in the shuttle run (p = .023).

When analyzing the significant differences, relevant values were obtained in relation to controlling motivation between the girls in the experimental group and the girls in the control group. Girls in the experimental group showed higher values on the post-test (1.053; p = .034). Both groups (experimental and control) showed an improvement in IPA values when comparing the values obtained in the pre-test and post-test. With regard to the boys, it is worth noting the decrease in the personal and social component of the PSRQ, which led to significant differences between the pre- and post-test in favor of the group that carried out the program.

Discussion of Results

The results indicate that the students who received the TPSR model hybridized with other PM—the SEM, health-related PE, the Attitudinal Style, and Cooperative Learning—showed improvements in all physical fitness tests (sit and reach, standing broad jump, medicine ball throw, and shuttle run). This was the case for the girls, who achieved significant improvements in all the tests performed, as well as for the boys, who also improved except in the sit and reach. By contrast, the group that was taught through a more traditional methodology did not show improvements in the sit and reach test; however, in the other tests, both the girls and the boys improved. In their study, Melero-Cañas et al. (2021) hybridized the TPSR model with gamification and found improvements in the speed-agility test. Likewise, it is worth highlighting the article by Carcas-Vergara et al. (2024), who, despite not using a hybridization of PM, compared the ludotechnical model with the traditional one and obtained similar improvements in both.

These results suggest that hybridizing the TPSR model with other pedagogical models is just as effective as traditional methodology in terms of physical fitness. However, with the intention of adapting to new curricula, which propose placing students at the center of learning, it is advisable to move away from more traditional methodologies and approach more innovative ones.

One of the goals set by PE teachers is to increase students’ PA practice, especially during adolescence. In our study, we observed that the group of girls, both in the control and experimental groups, showed an intention to be more physically active after the intervention. These results are similar to those reported by García-Castejón et al. (2021), who hybridized the TPSR model with TGfU, and not only achieved improvements in the IPA but also in psychosocial variables. Prat et al. (2019) argued that the use of the TPSR model generates a climate of greater participation, effort, commitment, and leadership, characteristics that foster more positive experiences in PE classes and, in turn, encourage more physical activity practice outside school hours. Merino-Barrero et al. (2020), for their part, also found that applying the TPSR model, compared to direct instruction, in secondary school improved students’ intention to be physically active outside school.

On the other hand, regarding student motivation, the calculation of the SDI showed improvements in both groups, although in neither case were they significant. Valero-Valenzuela et al. (2020) observed that applying a hybridization of the TPSR model with gamification resulted in a decrease in amotivation and an increase in the SDI, just as García-García et al. (2023) found with regard to prosocial behaviors. Merino-Barrero et al. (2020) reported that applying the TPSR model could promote more self-determined motivation and reduce amotivation. Other authors who also found improvements in intrinsic and introjected motivation were Manzano and Valero-Valenzuela (2019), who applied the TPSR model in subjects other than PE. Jorquera-Jordan (2022), in a systematic review on the effect of the TPSR model on student motivation, concluded that the TPSR model is closely related to more self-determined forms of motivation. When analyzing the levels of motivation within the TPSR model, it is observed that they initially stem from a more external locus and gradually move toward a more internal locus. This evolution is reflected in the fact that at the beginning there are greater external rewards and more teacher control, whereas in the later levels supervision and rewards are reduced (García-González, 2021).

With respect to basic psychological needs (autonomy, relatedness, and competency), our study did not find significant improvements in any of the three. This differs from other studies such as that of Menéndez-Santurio and Fernández-Río (2017), who hybridized the SEM and the TPSR model, and found improvements in competency and relatedness, though not in autonomy. Similarly, Quiñonero-Martínez et al. (2023), through hybridizing the TPSR and SEM, reported progress in psychological needs. Prat et al. (2019) illustrated that applying the TPSR model generated a favorable perception among students regarding their basic psychological needs. The hybridization of game invention with the materials self-construction model (Méndez-Giménez & Garví-Medrano, 2025) fostered perceptions of autonomy, competency, and sense of belonging in the experimental group compared to the control group.

Finally, regarding the results obtained in the PSRQ, no significant improvements were observed in either of the two factors, despite the fact that activities were implemented where students had to help one another to achieve collective benefit. These results differ from those of other authors such as Manzano-Sánchez et al. (2019) or Pozo et al., (2018), who found improvements in personal and social responsibility after implementing specific programs based on the TPSR model. Llopis-Goig et al. (2011), for their part, recommend that for responsibility-development programs to be more effective, implementation should extend to other subjects and teachers. Wright & Burton (2008) also propose combining the questionnaire with other techniques, such as observation, in-depth interviews, or focus groups. In this case, it is worth highlighting that the students in the experimental group who participated in the TPSR model, once the implementation was completed, answered questions related to their personal and social responsibility. The majority responded that the model had allowed them to improve their responsibility when learning to work individually and in groups, thanks to the different methodologies applied throughout the year (e.g., group roles and expert groups).

Conclusions and Limitations of the Study

The aim of the study was to analyze the implementation of the TPSR model and its hybridization with other PM—the Attitudinal Style, Cooperative Learning, the SEM, and health-related PE—compared to traditional methodology, in relation to student motivation, intention to be physically active, satisfaction of basic psychological needs, personal and social responsibility, and performance in different physical fitness tests, as well as by gender. The results obtained show significant improvements in the experimental group in the different physical condition tests in both sexes, together with the intention of the girls to be more physically active. Therefore, the hybridization of PM, unlike traditional methodologies, allows placing the student at the center of the teaching-learning process, carrying out a more individualized education, adapted to the different contexts that can be found in the classroom. Furthermore, it has been observed that this approach enables the development of different subject-specific competencies and knowledge in PE, as well as transversal competencies that are fostered across all areas, subjects, and projects.

The ultimate goal is not only the acquisition of knowledge but also learning how to use it to respond to the main challenges students will face throughout life. To this end, it is important to design LS that present scenarios similar to those they may encounter in real life, influencing in a multicomponent and multilevel way to promote greater impact on students.

The main limitations of this study were, first, that the students had no previous experience with the implementation of pedagogical models in PE. Second, the teacher had little experience in applying the TPSR model and the other models with which it was hybridized, although they gradually evolved through observation and reflection on the sessions carried out with each group. Another limitation was that the teacher of the control group, besides being the PE teacher, also taught French. Finally, it would have been appropriate to analyze the effect of each hybridization separately, rather than the effect of the combination of all of them over the course of the academic year.

Future lines of research should consider the possibility of applying pedagogical hybridization in different secondary school grades and throughout the educational process, to see how it develops with age. Another relevant aspect would be to implement it in different educational contexts, such as schools with maximum complexity or post-compulsory studies, to assess whether it has the same applicability.

Practical Applications

Based on this study, it is recommended to hybridize different pedagogical models and to follow the practical guidelines below:

- Adapt pedagogical models to the specific context of each school, as every setting has its own needs.

- Try to ensure that the final outcome of each Learning Situation can be transferred to real-life contexts today and involve the different spheres of influence proposed in the socioecological model (e.g., accompanying a sedentary person, exploring the PA options available in the community, designing training programs for different fitness levels).

- Promote the acquisition of healthy habits throughout the academic year, for example, through a “healthy passport,” where students earn badges related to challenges (such as bringing a healthy lunch, participating in sports events, meeting recommended sleep hours, etc.).

- Provide a wide variety of knowledge/contents to be worked on, ensuring that they are as innovative as possible, given their direct relationship with student motivation.

By following these pedagogical recommendations, the aim is to foster a quality and meaningful PE for all students—in short, a PE that motivates them and helps ensure that, as adults, they will want to and know how to practice PA in their free time, while also maintaining healthy lifestyle habits that contribute to better health.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the support of the Departament de Recerca i Universitats of the Generalitat of Catalonia to the Grup de Recerca i Innovació en Dissenys (GRID) in the line Technology and multimedia and digital application in observational designs (Code: 2021 SGR 00718) and the support of the Spanish Government project LINCE PLUS: Multimodal platform for data integration, synchronization and analysis in physical activity and sport [PID2024-156051NB-I00] (2025–2027). (Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, State Research Agency and European Union).

References

[1] Baena-Extremera, A., Granero-Gallegos, A., Gómez-López, M., & Abraldes, J. A. (2014). Orientaciones de Meta y Clima Motivacional Según Sexo y Edad en Educación Física. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 9(26), 119-128. Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia. Murcia, España. www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=163036900007

[2] Barbosa-Granados, S. H., & Urrea-Cuéllar, Á.M. (2018). Influencia del deporte y la actividad física en el estado de salud físico y mental: una revisión bibliográfica. Katharsis, (25), 155–173. doi.org/10.25057/25005731.1023

[3] Barrett, T. (2005). Effects of cooperative learning on the performance of sixth-grade physical education students. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 24(1), 88–102. doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.24.1.88

[4] Carcas-Vergara, E., Cordellat-Marzal, A., Valero-Valenzuela, A. & Jiménez-Parra, J. F. (2024). Impact of the ludotechnical model on motivational variables in elementary school: perceptions and gender differences. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 159, 18-31. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2025/1).159.03

[5] Anguera, M. T., Camerino, O and Castañer, M (2012): Mixed methods procedures and designs for research on sport, physical education and dance. In O. Camerino, M. Castañer and M.T. Anguera, (Ed.): Mixed Methods Research in the Movement Sciences: Cases in Sport, Physical Education and Dance. UK. Routledge. ISBN - 978-0-415-67301-3

[6] Conseil de l´Europe (1989). EUROFIT. Revista de Investigación, Docencia, Ciencia, Educación Física y Deportiva,(12),8–49.

[7] Deci, E. L. y Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268. doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

[8] Escartí, A., Gutiérrez, M., & Pascual, C. (2011). Propiedades psicométricas de la versión española del “Cuestionario de responsabilidad personal y social” en contextos de educación física. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 20(1), 119-130.

[9] Escartí, A., Wright, P. M., Pascual, C., & Gutiérrez, M. (2015). Tool for Assessing Responsibility-based Education (TARE) 2.0: Instrument revisions, inter-rater reliability, and correlations between observed teaching strategies and student behaviors. Universal journal of psychology, 3(2), 55–63. doi.org/10.13189/ujp.2015.030205

[10] Fernández Río, J., & Saiz-González, P. (2023). Educación Física con Significado (EFcS). Un planteamiento de futuro para todo el alumnado. Revista Española De Educación Física Y Deportes, 437(4), 1–9. doi.org/10.55166/reefd.v437i4.1129

[11] Fernández Río, J., Calderón, A., Hortigüela-Alcalá, D., Pérez-Pueyo, A., & Aznar Cebamanos, M. (2016). Pedagogical models in physical education: theoretical and practical considerations for teachers. Revista Española De Educación Física Y Deportes, (413), Pág. 55-75.

[12] Fernández Río, J., Hortigüela Alcalá, D., & Pérez Pueyo, Á. L. (2021). ¿Qué es un modelo pedagógico? Aclaración conceptual. Los modelos pedagógicos en educación física: qué, cómo, por qué y para qué, 12–24. Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de León.

[13] García-Castejón, G., Camerino, O., Castañer, M., Manzano-Sánchez, D., Jiménez-Parra, J. F., & Valero-Valenzuela, A. (2021). Implementation of a Hybrid Educational Program between the Model of Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR) and the Teaching Games for Understanding (TGfU) in Physical Education and Its Effects on Health: An Approach Based on Mixed Methods. Children, 8(7), 573. doi.org/10.3390/children8070573

[14] García-García, J., Belando-Pedreño, N., Fernández-Río, F. J. & Valero-Valenzuela, A. (2023). Prosocial Behaviours, Physical Activity and Personal and Social Responsibility Profile in Children and Adolescents. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 153, 79–89. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2023/3).153.07

[15] García-González, L. (2021). Cómo motivar en educación física: Aplicaciones prácticas para el profesorado desde la evidencia científica. Servicio de publicaciomnes de la Universidad de Zaragoza. Zaragoza. doi.org/10.26754/uz.978-84-18321-22-1

[16] Gómez-Mármol, A., Sánchez-Alcaraz, B. J., De la Cruz, E., Valero, A., and González-Villora, S. (2017). Personal and social responsibility development through sport participation in youth scholars. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 17, 775–782. doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2017.02118

[17] González-Cutre, D., Sicilia, Á., & Fernández, A. (2010). Hacia una mayor comprensión de la motivación en el ejercicio físico: medición de la regulación integrada en el contexto español. Psicothema, 22(4), 841-847

[18] González-Víllora, S., Evangelio, C., Sierra-Díaz, J., & Fernández-Río, J. (2018). Hybridizing pedagogical models: A systematic review. European Physical Education Review, 25(4), 1056–1074. doi.org/10.1177/1356336X18797363

[19] Hellison, D. (2011). Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility Through Physical Activity (3 ed.). USA: Human Kinetics.

[20] Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

[21] Jorquera-Jordan, J. (2022, 24-26 febrero). Efectos del modelo de responsabilidad personal y social sobre la motivación del alumnado: revisión sistemática [Comunicación en congreso]. Congreso Mundial de Educación EDUCA 2022, Santiago de Compostela, España.

[22] Llopis-Goig, R., Escarti, A., Pascual, C., Gutiérrez, M., & Marín, D. (2011). Fortalezas, dificultades y aspectos susceptibles de mejora en la aplicación de un Programa de Responsabilidad Personal y Social en Educación Física. Una evaluación a partir de las percepciones de sus implementadores. Culture and Education, 23(3), 445-461. doi.org/10.1174/113564011797330324

[23] Ludick, J. E. O. (2018). Efectos de los estilos de vida saludables en las habilidades sociales en jóvenes. Vertientes. Revista especializada en ciencias de la salud, 20(2), 5-11. Retrieved from www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/vertientes/article/view/67161

[24] Manzano, D. & Valero-Valenzuela, A. (2019). El Modelo de Responsabilidad Personal y Social (MRPS) en las diferentes materias de la Educación Primaria y su repercusión en la responsabilidad, autonomía, motivación, autoconcepto y clima social. Journal of Sport and Health Research. 11(3): 273-288.

[25] Manzano-Sánchez, D., Valero-Valenzuela, A., Conde-Sánchez, A., & Chen, M.-Y. (2019). Applying the personal and social responsibility model-based program: differences according to gender between basic psychological needs, motivation, life satisfaction and intention to be physically active. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2326. doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132326

[26] McLennan, N. & Thompson, J. (2015). Educación Física de Calidad. Guía para los responsables políticos. Ediciones UNESCO. Open access. Full text. unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000231340

[27] McLeroy, K. R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., & Glanz, K. (1988). An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351–377. doi.org/10.1177/109019818801500401

[28] Melero-Cañas, D., Morales-Baños, V., Manzano-Sánchez, D., Navarro-Ardoy, D., & Valero-Valenzuela, A. (2021). Effects of an Educational Hybrid Physical Education Program on Physical Fitness, Body Composition and Sedentary and Physical Activity Times in Adolescents: The Seneb’s Enigma. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 629335. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.629335

[29] Menéndez Santurio, J. I., & Fernández-Río, J. (2017). Responsabilidad social, necesidades psicológicas básicas, motivación intrínseca y metas de amistad en educación física (Social responsibility, basic psychological needs, intrinsic motivation, and friendship goals in physical education). Retos, 32, 134–139. doi.org/10.47197/retos.v0i32.52385

[30] Méndez-Giménez, A., & Garví-Medrano, P. M. (2025). Motivational and Social Effects of a Hybridization of Student-designed games + Student-made Material in Physical Education. Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 18(37), 60–74. doi.org/10.25115/ecp.v18i37.10058

[31] Merino-Barrero, J. A., Valero-Valenzuela, A., Pedreño, N. B., & Fernandez-Río, J. (2020). Impact of a sustained TPSR program on students’ responsibility, motivation, sportsmanship, and intention to be physically active. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 39(2), 247–255. doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2019-0022

[32] Moral García, J. E., Román-Palmero, J., López García, S., Rosa Guillamón, A., Pérez Soto, J. J., & García Cantó, E. (2019). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Motivación Deportiva y análisis de la motivación en las clases de educación física y su relación con nivel de práctica de actividad física extraescolar. Retos, 36, 283–289. doi.org/10.47197/retos.v36i36.67783

[33] Moreno, J. A., González-Cutre, D., Chillón, M., & Parra, N. (2008). Adaptación a la Educación Física de las Escala de las Necesidades Psicológicas Básicas en el Ejercicio. Revista Mexicana de Psicología, 25, 295-303.

[34] Moreno, J. A., Moreno, R., y Cervelló, E. (2007). El autoconcepto físico como predictor de la intención de ser físicamente activo. Psicología y Salud, 17(2), 261-267.

[35] Murillo, B., Julián, J. A., García-González, L., Abarca-Sos, A., & Zaragoza, J. (2014). Effect of gender and contents on physical activity and perceived competence in Physical Education. RICYDE. Revista Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte, 10(36), 131–143. dx.doi.org/10.5232/ricyde2014.03604

[36] Organización Mundial de la Salud (2020). WHO Guidelines on physical activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization.

[37] Pérez-Juste, R., Galán-González, A. & Quintanal-Díaz, J. (2012). Métodos y Diseño de Investigación en Educación. Edición Digital. UNED.

[38] Pérez-Pueyo, A., Hortigüela-Alcalá, D., & Fernández-Río, J. (2021). Modelos Pedagógicos en Educación Física: qué, cómo, por qué y para qué. Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de León.

[39] Plan de acción mundial sobre actividad física 2018-2030. Más personas activas para un mundo sano. Washington, D.C.: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2019. Licencia: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

[40] Pozo, P., Grao-Cruces, A., & Pérez-Ordás, R. (2018). Teaching personal and social responsibility model-based programmes in physical education: A systematic review. European Physical Education Review, 24(1), 56–75. dx.doi.org/10.1177/1356336X16664749

[41] Prat, Q., Camerino, O., Castañer, M., Andueza, J., & Puigarnau, S. (2019). The Personal and Social Responsibility Model to Enhance Innovation in Physical Education. Educación Física y Deportes, 136, 83–99. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2019/2).136.06

[42] Quiñonero-Martínez AL, Cifo-Izquierdo MI, Sánchez-Alcaraz Martínez BJ and Gómez-Mármol A (2023). Effect of the hybridization of social and personal responsibility model and sport education model on physical fitness status and physical activity practice. Front. Psychol. 14:1273513. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1273513

[43] Ribero, E., González-Silva, J., Conejero, M., & Fernández-Echeverría, C. (2024). Actividad física y satisfacción de las necesidades psicológicas básicas en adolescentes de distinto sexo en contextos rurales. Retos, 61, 501–509. doi.org/10.47197/retos.v61.108793

[44] Ruiz, J. R., España Romero, V., Castro Piñero, J., Artero, E. G., Ortega, F. B., Cuenca García, M., Jiménez Pavón, D., Chillón, P., Girela Rejón, M.ª J., Mora, J., Gutiérrez, A., Suni, J., Sjöstrom, M., & Castillo, M. J.. (2011). Batería ALPHA-Fitness: test de campo para la evaluación de la condición física relacionada con la salud en niños y adolescentes. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 26(6), 1210-1214

[45] Sánchez-Alcaraz, B. J., Ros, E., Alfonso-Asensio, M., Hellín-Martínez, M., Gómez-Marmol, A. (2021). Responsabilidad personal y social y práctica de actividad física en estudiantes. E-balonmano Com 17(2), 171-180.

[46] Shen, Y., & Shao, W. (2022). Influence of Hybrid Pedagogical Models on Learning Outcomes in Physical Education: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9673. doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159673

[47] Sicilia, A. & Delgado, M.A. (2002). Educación Física y estilos de enseñanza. Aplicación de la participación del alumnado desde un modelo socio-cultural del conocimiento escolar. Barcelona: Inde.

[48] Slingerland, M., & Borghouts, L. (2011). Direct and indirect influence of physical education-based interventions on physical activity: a review. Journal of physical activity & health, 8(6), 866–878. doi.org/10.1123/jpah.8.6.866

[49] Valero-Valenzuela, A., Gregorio García, D., Camerino, O., & Manzano, D. (2020). Hybridisation of the Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility Model and Gamification in Physical Education. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 141, 63–74. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2020/3).141.08

[50] Vallerand, R.J. (1997). Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. In M. P. Zanna (ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 271-360). New York: Academic Press

[51] Wright, P. M. & Burton, S. (2008). Implementation and outcomes of a responsibility-based physical activity program integrated into an intact high school physical education class. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 27 (2), 138–154. doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.27.2.138

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: January 17, 2025

Accepted: June 30, 2025

Published: October 1, 2025

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en