Tendencies in Action, Type of Sport and Training Style in Sportswomen

José A. Cecchini Estrada

*Corresponding author: Antonio Méndez Giménez mendezantonio@uniovi.es

Cite this article

Cecchini, J.A., Méndez-Giménez, A., Fernández-Río, J., Carriedo, A., & Sánchez-Martínez, B. (2022). Tendencies in Action, Type of Sport and Training Style in Sportswomen. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 149, 63-72. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2022/3).149.07

Abstract

The main objective of the study was to analyse whether there are differences in the action tendencies (assertive, aggressive and submissive) of female athletes depending on the type of sport they play (contact, non-contact). Research suggests that participants in non-contact sports show more mature reasoning regarding moral dilemmas of action tendencies in sport than participants in medium-high contact sports. 272 female athletes (149 from non-contact sports; 123 from contact sports) aged 11-16 years (M = 13.48, SD = 1.93) responded to three questionnaires. Different generalised linear models were tested and in all of them the type of sport (contact, non-contact) predicted assertive and aggressive action tendencies in sport in the presence of assertive and aggressive action tendencies in other contexts (trait) and the coach’s interpersonal style. The results suggest that the type of sport played shapes action tendencies related to moral dilemmas in female athletes.

Introduction

In recent years, a growing body of theoretical and empirical literature has emerged, addressing the study of the relationships between moral thinking, tendencies and action and the practice of sport (Nascimento Junior et al., 2020). In order to examine these relationships, researchers have employed different strategies, which are presented below together with the results obtained:

a) Comparative analysis:

a1) Between athletes and non-athletes (e.g. university students who play sport versus university students who do not play sport). College basketball players reasoned at a less mature level than their non-athlete counterparts (Bredemeier & Shields, 1984), both as regards reasoning of moral dilemmas in sport and in other contexts (Bredemeier & Shields, 1986).

a2) Between different types of sport (e.g. high-contact versus low-contact sports). Participants in different types of sports showed no significant differences in the development of moral reasoning (Proios et al., 2004). College students who participate in individual sports showed higher levels of moral reasoning than college students who participate in team sports (Priest et al., 1999). Team sports players showed lower levels of concern for the opponent than individual sports players (Vallerand et al., 1997).

a3) Between different levels of sport practice (e.g. elite versus trainee athletes). Elite athletes showed poorer moral reasoning than trainee athletes (Shrout et al., 2017). A similar trend was observed among professional and amateur handball players (Fruchart & Rulence-Paques, 2014).

b) Correlational studies between the degree of sport involvement and moral thinking, tendencies and action in sporting contexts (e.g. relationships between levels of sport practice and fair play). Boys’ levels of participation in high-contact sports and girls’ levels of participation in medium-contact sports correlated positively with less mature moral reasoning and greater aggressive tendencies (Bredemeier et al., 1986). In university athletes, participation in medium-high contact sports was associated with lower levels of fair play in the sport (Cecchini et al., 2007).

c) Explanatory studies that provide a sense of understanding regarding the phenomenon to which the results obtained in descriptive and correlational studies refer (e.g. the role of goal orientations in moral functioning). To explain these results, researchers analysed the influences of personal and contextual variables from different theoretical contexts. Among the former, they observed, for example, how goal orientations and sportsmanship orientations play a critical role in moral reasoning (Shrout, 2017). Furthermore, it was observed that participation in contact sports positively predicts ego-orientation, which in turn predicts low levels of moral functioning (Kavussanu & Ntoumanis, 2003), and low levels of fair play (Cecchini et al., 2007). Additionally, the manner in which self-determined motivation positively predicts sportsmanship orientations, subsequently predicting aggression in sport was observed (Chantal et al., 2005). Competition orientation was also a powerful predictor of sportsmanship (Shields et al., 2016).

Among the contextual variables, the climate created by parents, peers and coaches was analysed. For example, the performance climate in training sessions significantly predicted low levels of morality in sport, whereas the perceived mastery climate predicted more mature moral reasoning (Miller et al., 2004). The relationship between the mother and father-initiated learning climate/enjoyment was also found to be moderately and positively associated with prosocial attitude (Wagnsson et al., 2016). Other studies addressed controlling behaviours by the coach and found that these predict frustration of the athlete’s basic psychological needs, which in turn predicts low moral functioning and doping intentions/doping use (Ntoumanis et al., 2017). An indirect relationship has also been found between the meta-perception of competence of multiple significant others and different orientations towards sportsmanship (Cecchini et al., 2014). Delrue et al. (2017) demonstrated how variation in coaches’ frustration of athletes’ basic psychological needs was related from one football match to the next to variation in antisocial behaviour towards the opponent. Another variable that has been taken into account is the moral atmosphere of the team. For example, athletes’ perceptions of their team’s moral atmosphere were found to have a significant effect on moral functioning (Kavussanu et al., 2002), and a favourable moral atmosphere was positively associated with more prosocial behaviour in sport (Rutten et al., 2011).

Based on this background and, considering the fact that sport-related moral thinking, tendency and action also depend on the gender of the participants (Martin et al., 2017), the main aim of the present study was to analyse whether there are differences in young female athletes’ action tendencies (assertive, aggressive and submissive) in sport and in other contexts of everyday life depending on the type of sport they play (contact, non-contact). This is the first study to address this issue, so it is considered premature to establish a hypothesis. However, differences between types of sports in the more general context of moral reasoning have not been conclusive because, while some studies showed no significant differences in the development of moral reasoning between participants in different types of sports (Proios et al., 2004), others did (Priest et al., 1999). The second objective was to determine whether assertiveness, aggressiveness and submissiveness in sport are related to the type of sport played (contact, non-contact) once the respective effects of assertiveness, aggressiveness and submissiveness in everyday life have been accounted for. Finally, perceptions of interpersonal styles were added to the model (satisfaction/frustration of athletes’ basic psychological needs by the coach). For the latter two objectives, no hypotheses were made as they are being studied for the first time.

Methodology

Participants

Convenience sampling was used. The sample consisted of 272 female athletes, 149 of whom were involved in non-contact sports (badminton: n = 43, inline skating, n = 19, synchronised swimming: n = 51, and triathlon: n = 36), and 123 participants involved in sports where there is physical contact with the opponent (basketball: n = 105, rugby: n = 18), aged between 11 and 16 (M = 13.48, SD = 1.93) from a city in northern Spain. There was no sample mortality.

Materials and methods

Assertive, aggressive and submissive action tendencies. The version of CATS (Children’s Action Tendency Scale) translated into Spanish by Cecchini et al. (2009) was used, which raises moral dilemmas about assertive, aggressive and submissive attitudes and behaviour in children (Deluty, 1979). The participant must answer questions that involve situations of frustration, provocation and conflict (e.g. “You have just left school. A child smaller than you throws a stone at you and it hits you on the head. What would you do?”). Each of the situations is followed by three alternatives (aggression: “Give him a good ‘beating’ so that he ‘knows’ how much it hurts”; assertiveness: “Scold him by telling him that throwing stones at people’s heads is very dangerous”, and submission: “Ignore him”), presented in contrast (assertiveness versus aggression, assertiveness versus submission, and submission versus aggression), so that they are forced to compare and choose the best alternative. In this study, the reduced version of six questions has been used, resulting in eighteen responses. The total scores for each subscale (assertiveness, aggressiveness and submissiveness) range from 0 to 12 points. In the present research the internal consistency of each subscale has been examined by the Kuder-Richardson formula (K-R 20) for dichotomous responses. The values were as follows [in brackets are the values obtained by Bredemeier (1994); also with a shortened version of the questionnaire]: assertiveness = .60 (.54), aggressiveness = .82 (.80) and submission = .63 (.58).

Assertive, aggressive and submissive action tendencies in sport. The version of SCATS (Sport Children’s Action Tendency Scale) translated into Spanish by Cecchini et al. (2009) was used, which poses moral dilemmas about attitudes and behaviours of these same variables in sport-specific situations (Bredemeier, 1994). The structure is the same as the Child Action Tendencies Scale (CATS). The participant must answer questions that also involve conflict situations (“You are the fastest runner in your school. A new boy comes to school and boasts that he can beat you without difficulty. You decide to compete with him. Near the end of the race you’re in the lead, but then you twist your ankle. What would you do?) Each of the scenarios is followed by three alternatives (aggression: “I would use my elbows to keep him behind me so I could beat him”; assertiveness: “I would stop and challenge him to a new race when my ankle gets better”, and submission: “I would finish the race as best I could and not tell anyone about my ankle”), presented in contrast (assertiveness vs. aggression, assertiveness vs. submission, and submission vs. aggression). The total scores for each subscale range from 0 to 20 points. The Kuder-Richardson values for dichotomous responses were as follows (original scale values in brackets): assertiveness = .72 (.68), aggressiveness = .89 (.85) and submission = .69 (.66).

Coach’s interpersonal style. In order to assess the athletes’ perceptions of their coaches’ instructional style, the Coaches’ Interpersonal Style Questionnaire (Pulido et al., 2017) was used. This instrument consists of 24 items designed to assess athletes’ perceptions of their coaches’ supportive and frustrating behaviours as regards athletes’ psychological needs. The questions are preceded by the statement “During practice, our coach…”. The scale consists of six factors (four items per factor): Autonomy support (e.g. “… often asks us about our preferences regarding the activities/tasks to be performed”), Competence support

(“… proposes exercises adjusted to our level so that we can do them well”), Relationship support (“… always encourages good relationships between teammates”), Autonomy frustration (“… prevents me from making decisions about how I play”), Competence frustration (“… proposes situations that make me feel incapable”), and Relationship frustration (“… sometimes I have felt rejected by him/her”). All responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha values were respectively .72, .82, .80, .72, .87, and .75.

Procedure

Informed consent was obtained from parents, coaches and presidents of the sports clubs. The questionnaires were anonymous and the athletes were assured that their answers would not be read by their coaches or parents. All questionnaires were completed under the supervision of an experienced researcher. Data were collected immediately after a training session. Respondents took approximately 30 minutes to complete the questionnaires. Permission was granted by the Ethics Committee of the University of Oviedo.

Data analysis

All data were analysed using SPSS 24.0. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (with Lilliefors correction) was used to test whether or not the data set fit a normal distribution. Using a significance level of 5% it was concluded that none of the variables used in this study had a normal distribution. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine the differences between the groups (contact versus non-contact sports) for the variables under study. Bivariate correlations were established using Spearman’s Rho test. To determine whether the sport (contact, non-contact) was related to moral reasoning in sport, independently of moral reasoning in general, different generalised linear models (GLM) were constructed, taking as the dependent variable the athletes’ moral reasoning about (a) assertive, (b) aggressive, and (c) submissive behaviours in sport, and as predictor variables the type of sport (contact, non-contact), and the athletes’ reasoning about (a1) assertive, (b1) aggressive and (c1) submissive behaviours in other contexts of everyday life. Furthermore, in order to uncover the relationship between moral reasoning and the coach’s satisfaction/frustration of basic psychological needs, the six dimensions of the questionnaire and all their possible outcomes were included in the model. Age was also included as a contrast variable. The GLM establishes how the dependent variable was related to the factors and covariates through a certain link function. In addition, the model allows the dependent variable to display a non-normal distribution. In the construction of the GLM, different factors and covariates were incorporated until no significant improvement in the model was obtained. Non-significant variables were excluded from the model to avoid over-parametrisation that would dilute other effects (Punsly & Deriso, 1991). The most appropriate model was the one that minimised the residual deviation. In the case of heteroscedasticity in the residuals of the model the robust estimator option is used. For the interpretation of the results, the omnibus test was used (if not significant, the analysis is terminated). Goodness-of-fit measures, based on deviation and AIC values, were then assessed.

Results

Differences between groups

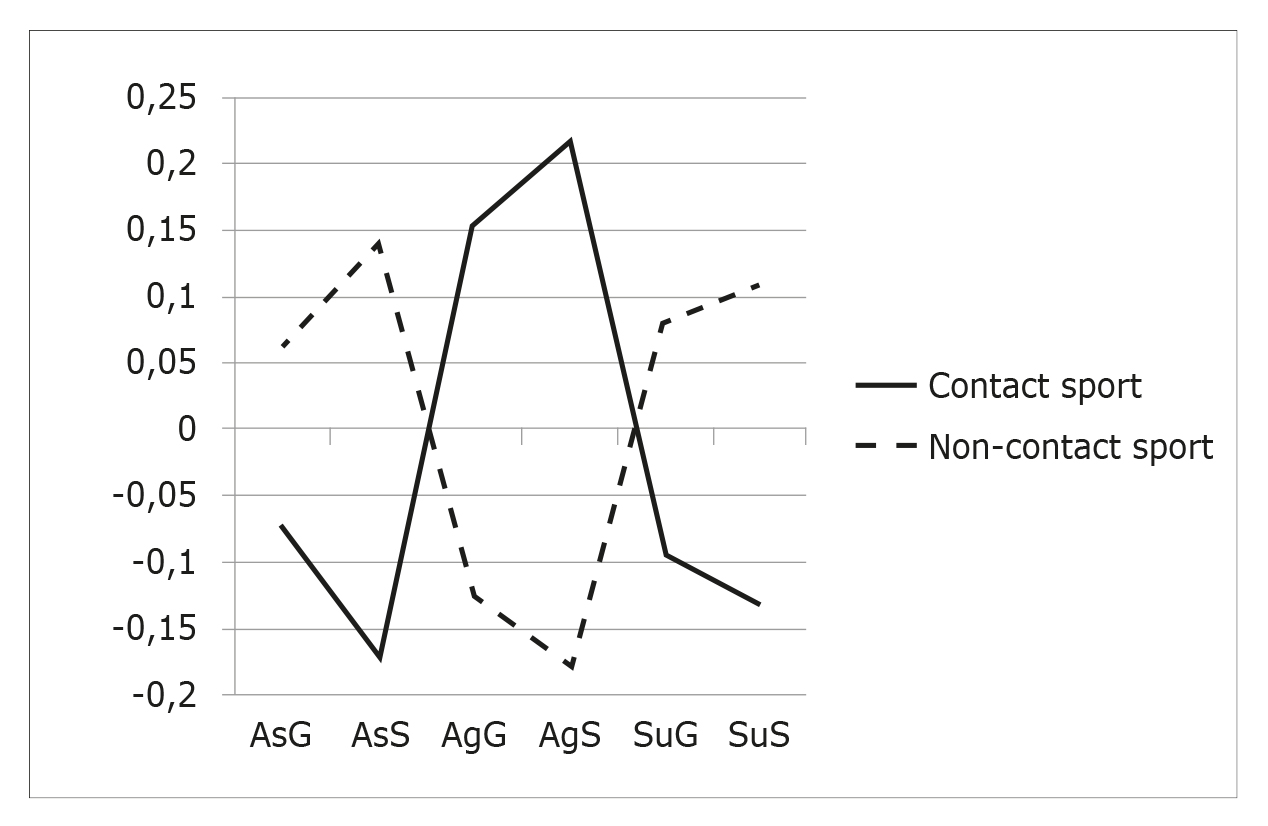

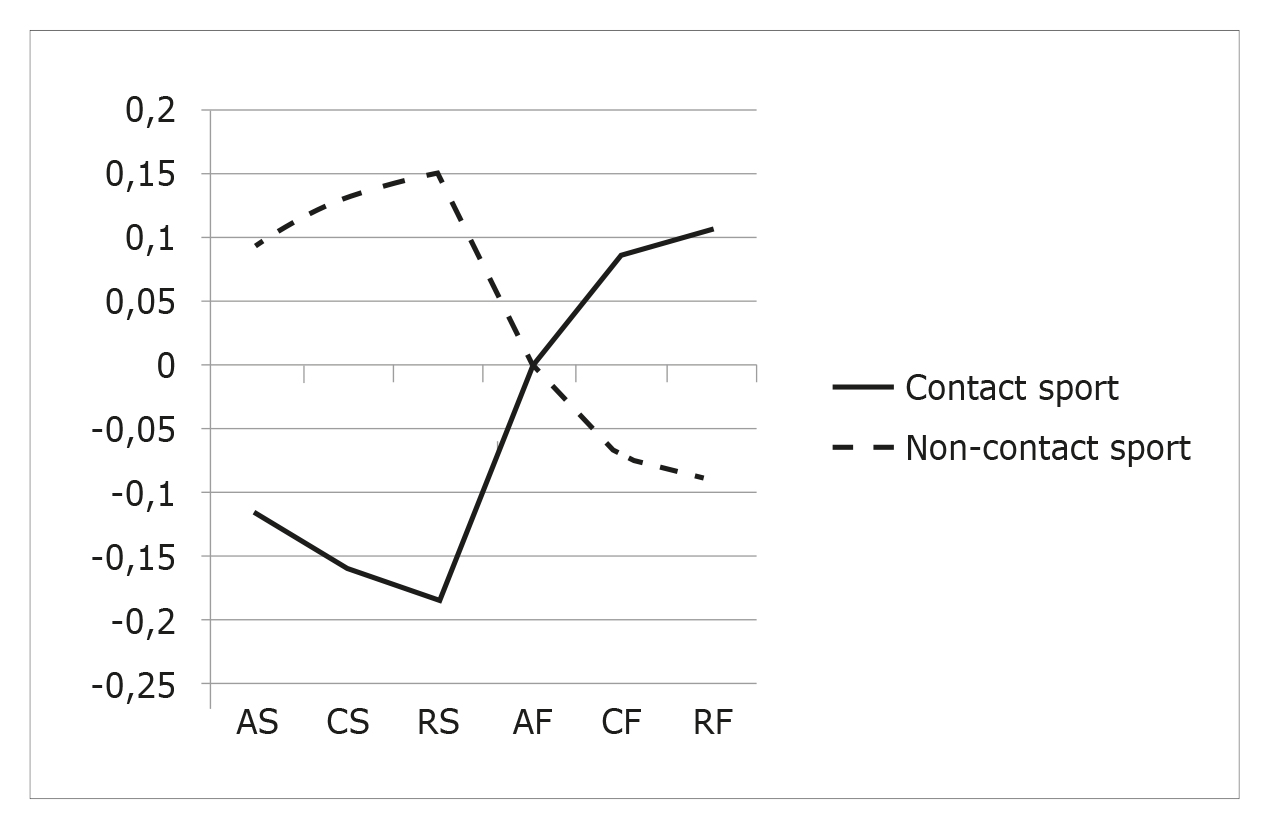

Participants showed statistically significant differences on six variables according to the type of sport played. Women in contact sports scored higher on aggressive action tendencies in sport and in other contexts, and lower on assertive action tendencies and submissive action tendencies in sport than women in non-contact sports (Table 1). As reasoning of action tendencies was quantified on the basis of dichotomous questions, it could be concluded that the group of athletes who play contact sports had lower levels of moral reasoning than athletes who play sports in which there is no physical contact between participants. It was also observed that players of non-contact sports perceived a higher degree of satisfaction regarding basic psychological needs of competence and relationship from their coach. Figures 1 and 2 show a clear trend towards more adaptive behaviour in the non-contact group, both in moral reasoning and in satisfaction/frustration of basic psychological needs by the coach, except for frustration of autonomy.

Table 1

Descriptive analyses and differences between groups (contact versus non-contact sports) of the variables under study.

Note: AsG = General Assertiveness, AsS = Assertiveness in sport, AgG = General Aggressiveness, AgS = Aggressiveness in sport, SuG = General Submission, SuS = Submission in sport.

Note: AS = Autonomy Satisfaction, CS = Competence Satisfaction, RS = Relationship Satisfaction, AF = Autonomy Frustration, CF = Competence Frustration, RF = Relationship Frustration.

Bivariate correlations

Both in the sporting context and in life in general, the highest correlations between the three variables measuring action tendencies were between submissiveness and aggressiveness. All three action tendencies in everyday life correlated positively with the corresponding variable in sport, although aggressiveness showed the highest correlation. In sport, these same dimensions showed a higher degree of correlation with the variables measuring satisfaction/frustration of basic psychological needs by the coach, except for the submission variable, which showed no relationship in the sporting context. A higher correlation was also observed in the sporting context for assertiveness and aggressiveness (negative and positive, respectively) with variables measuring frustration of basic psychological needs.

Generalised linear models

Table 3 presents the results of the GLMs with assertiveness in sport as a response variable. The omnibus test was significant (x2 = 50.146 (4), p < .001). Overall, the model explains 17% of the variance. Model 2 shows that in the presence of assertiveness in sport, the type of sport remains a significant variable, although it explains a very low percentage of the variance. In model 3 the frustration of competition variable is included, which increases the explained variance by 8%. Finally, model 4 incorporates relationship frustration, which explains a further 2% of the variance. Consequently, moral reasoning of assertiveness in sport is explained by assertiveness in general, the type of sport played (less assertiveness in contact sports), and the coach’s frustration of basic psychological needs regarding competence and relationship.

The results of the GLMs with aggression in sport as a response variable are shown in Table 4. The omnibus test was significant (x2 = 111.45 (3), p < .001). Overall, the model explains 34% of the variance. In model 2 it is observed that, in the presence of general aggressiveness, sport type remains a significant variable, although it explains a low percentage of the variance. In model 3, the competence frustration variable is incorporated. Ultimately, moral reasoning of aggressiveness in sport is determined by aggressiveness in general, the type of sport played (higher aggressiveness in contact sports), and the coach’s frustration of basic psychological needs regarding competence.

In the omnibus test, the GLM results using sport submission as a response variable were significant (x2 = 48.390 (2), p < .001). Model 2 explains 16% of the variance. In this model it is observed that, in the presence of general submission, the type of sport is no longer a significant variable.

Discussion

The results of the study allow us to conclude that, in young female athletes, there are differences in assertive, aggressive and submissive action tendencies in sport depending on the type of sporting activity they practice (contact, non-contact). Participants in medium-high contact sports scored significantly higher on aggressive action tendencies than participants in non-contact sports, while participants in medium-high contact sports scored significantly higher on assertive and submissive tendencies. As these variables were measured in the present research, it can be affirmed that participants in non-contact sports show more mature reasoning regarding moral dilemmas of action tendencies in sport than participants in medium-high contact sports. This result is consistent with what has been observed in children (Bredemeier et al., 1986) and in university athletes (Cecchini et al., 2007; Priest et al., 1999), and contradicts what has been observed by Proios et al. (2004) in a much more heterogeneous population.

The results were less conclusive when action tendencies in other contexts of everyday life were analysed. While differences are observed in levels of aggressiveness (higher scores for contact sports participants, p < .05), they do not appear in assertiveness or submissiveness. In order to try to understand how these variables relate to each other (action tendencies in sporting and other contexts) and to address the second objective of the study, bivariate correlations were performed and different models (GLM) were tested. The bivariate correlations between the three action tendencies in everyday life with the corresponding variable in sport were found to be low (assertiveness) to moderate (aggressiveness), which determines that they are relatively independent. This is confirmed when the first GLMs are designed with the three dimensions of action tendencies in sport as outcome variables and the type of sport and the corresponding action tendency in everyday life as independent variables (models 2). In both assertive and aggressive action tendencies, the type of sport remains a significant predictor. In other words, the type of sport (contact, non-contact), predicts assertive and aggressive action tendencies in sport in the presence of assertive and aggressive action tendencies in other contexts (trait). These results are not observed in submission, this is believed to be because of the way these variables have been measured.

When satisfaction/frustration of basic psychological needs by the coach is included in the models, the variable with the greatest explanatory power for both assertive and aggressive action tendencies is competence frustration. This is consistent with the observations of Shields et al. (2016) on the relationship between competence orientation and sportsmanship. The relationship between frustration and aggression is also well documented. The results are also consistent with those observed for the relationship of satisfaction-frustration of basic psychological needs with victimisation (Menéndez-Santurio et al., 2020), and antisocial behaviour with adversarial behaviour (Delrue et al., 2017).

Finally, model 4 in the prediction of assertive tendency in sport also includes the relationship frustration variable in negative. Considering that assertiveness is an interpersonal and social communication skill, it seems logical to think that it is also linked to social relationship processes. Steps 3 and 4 decrease the explanatory power of sport type on the outcome variables, but do not cancel it out, so they cannot fully explain the relationship.

The present study has some limitations. The first is that it is based on a cross-sectional approach that cannot account for cause-effect relationships. The second is that the variables used do not fully explain the relationship between sport type and action tendencies in sport. Moreover, a third limitation is the fact that a dichotomous measurement has been carried out. For all these reasons, it is believed that new longitudinal and experimental studies should be carried out to explain this relationship by incorporating new variables such as respect, personal responsibility, sportsmanship and companionship.

Funding

This work has been subsidised by the company Fundación Cespa – Proyecto Hombre (Oviedo City Council).

References

[1] Bredemeier, B. J. (1994). Children’s moral reasoning and their assertive, aggressive, and submissive tendencies in sport and daily life. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 16(1), 1-14.

[2] Bredemeier, B. J., & Shields, D. (1984). Divergence in moral reasoning about sport and everyday life. Sociology of Sport Journal, 1, 348-357. http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/ssj.1.4.348

[3] Bredemeier, B. J., & Shields, D. L. (1986). Moral growth among athletes and nonathletes: A comparative analysis. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 147(1), 7–18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1986.9914475

[4] Bredemeier, B. J., Weiss, M., & Shields, D. (1986). The relationship of sport involvement with children’s moral reasoning and aggression tendencies. Journal of Sport Psychology, 8, 304-318. http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/jsp.8.4.304

[5] Cecchini, J. A., González, C., Alonso, C., Barreal, J. M., Fernández, C., García, M., Llaneza, R., & Nuño, P. (2009). Repercusiones del Programa Delfos sobre los niveles de agresividad en el deporte y otros contextos de la vida diaria. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 2, 34-41.

[6] Cecchini, J. A., González, C., & Montero, J. (2007). Participación en el deporte y fair play. Psicothema, 19, 57-64. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/727/72719109.pdf

[7] Cecchini, J. A., Méndez-Giménez, A., & Fernández-Río, J. (2014). Metapercepciones de competencia de terceros significativos, competencia percibida, motivación situacional y orientaciones de deportividad en jóvenes deportistas. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 23(2), 285-293.

[8] Chantal, Y., Robin, P., Vernat, J. P., & Bernache-Assolant, I. (2005). Motivation, sportspersonship and athletic aggression: a mediational analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 6, 233-249. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2003.10.010

[9] Delrue, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Mouratidis, A., Gevaert, K., Vande Broek, G., & Haerens, L. (2017). A game-to-game investigation of the relation between need-supportive and need-thwarting coaching and moral behavior in soccer. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 31, 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.03.010

[10] Deluty, R. H. (1979). Children’s Action Tendency Scale: A self-report measure of aggressiveness, assertiveness, and submissiveness in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47(6), 1061–1071. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.47.6.1061

[11] Fruchart, E., & Rulence-Paques, P. (2014). Condoning aggressive behaviour in sport: A comparison between professional handball players, amateur players, and lay people. Psicologica, 35, 585–600. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12424/902104

[12] Kavussanu, M., & Ntoumanis, N. (2003). Participation in sport and moral functioning: Does ego orientation mediate their relationship? Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 25, 1-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/jsep.25.4.501

[13] Kavussanu, M., Roberts, G. C., & Ntoumanis, N. (2002). Contextual influences on moral functioning of college basketball players. The Sport Psychologist, 16(4), 347 – 367. http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/tsp.16.4.347

[14] Martin, E. M., Gould, D., & Ewing, M. E. (2017). Youth’s perceptions of rule-breaking and antisocial behaviours: Gender, developmental level, and competitive level differences. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 15(1), 64-79. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2015.1055289

[15] Menéndez-Santurio, J. I., Fernández-Río, J., Cecchini, J. A., & González-Villora, S. (2020). Conexiones entre la victimización en el acoso escolar y la satisfacción-frustración de las necesidades psicológicas básicas de los adolescentes. Revista de Psicodidáctica. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psicod.2019.11.002

[16] Miller, B. W., Roberts, G., & Ommundsen, Y. (2004). Effect of perceived motivational climate on moral functioning, team moral atmosphere perceptions, and the legitimacy of intentionally injurious acts among competitive youth football players. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 20, 1–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2004.04.003

[17] Nascimento Junior, J. R., Silva, E. C., Freire, G. L. M., Granja, C. T. L., Silva, A. A., & Oliveira, D. V. (2020). Athlete’s motivation and the quality of his relationship with the coach. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 142, 21 28. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2020/4).142.03

[18] Ntoumanis, N., Barkoukis, V., Gucciardi, D. F., & Chan, D. K. C. (2017). Linking coach interpersonal style with athlete doping intentions and doping use: a prospective study. Journal Sport and Exercise Psychology 39, 188–198. http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2016-0243

[19] Priest, R. F., Krause, J. V., & Beach, J. (1999). Four-year changes in college athletes’ ethical value choices in sports situations. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 70, 170–178. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02701367.1999.10608034

[20] Proios, M., Doganis, G., & Athanailidis, I. (2004). Moral development and form of participation, type of sport, and sport experience. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 99, 633-642. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pms.99.2.633-642

[21] Pulido, J. J., Sánchez-Oliva, D., Leo, F. M., Sánchez-Cano, J., & García- Calvo, T. (2017). Development and validation of Coach’s Interpersonal Style Questionnaire (CIS-Q). Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 1–13.

[22] Rutten, E. A., Schuengel, C., Dirks, E., Stams, G. J. J., Biesta, G. J., & Hoeksma, J. B. (2011). Predictors of antisocial and prosocial behavior in an adolescent sports context. Social Development, 20(2), 294-315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2010.00598.x

[23] Shields, D. L., Funk, C. D., & Bredemeier, B. L. (2016). Conceptual metaphors and prosocial behavior. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 27, 213-221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.09.001

[24] Shrout, M. R., Voelker, D. K., Munro, G. D., & Kubitz, K. A. (2017). Associations between sport participation, goal and sportspersonship orientations, and moral reasoning. Ethics & Behavior, 27(6), 502-518. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1233494

[25] Vallerand, R. J., Deshaies, P., & Cuerrier, J. P. (1997). On the effects of the social context on behavioral intentions of sportsmanship. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 28(2), 126-140.

[26] Wagnsson, S., Stenling, A., Gustafsson, H., & Augustsson, C. (2016). Swedish youth football players’ attitudes towards moral decision in sport as predicted by the parent-initiated motivational climate. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 25, 110–114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.05.003

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: September 20, 2021

Accepted: February 17, 2022

Published: July 1, 2022

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en