Sport Events and Sustainability: A Systematic Review (1964-2020)

*Corresponding author: Maira Belen Ulloa muh2@alumnes.udl.cat

Cite this article

Ulloa-Hernández, M., Farías-Torbidoin, E. & Seguí-Urbaneja, J. (2023). Sporting events and sustainability. A systematic Review (1964-2020). Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 153, 101-113. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2023/3).153.09

Abstract

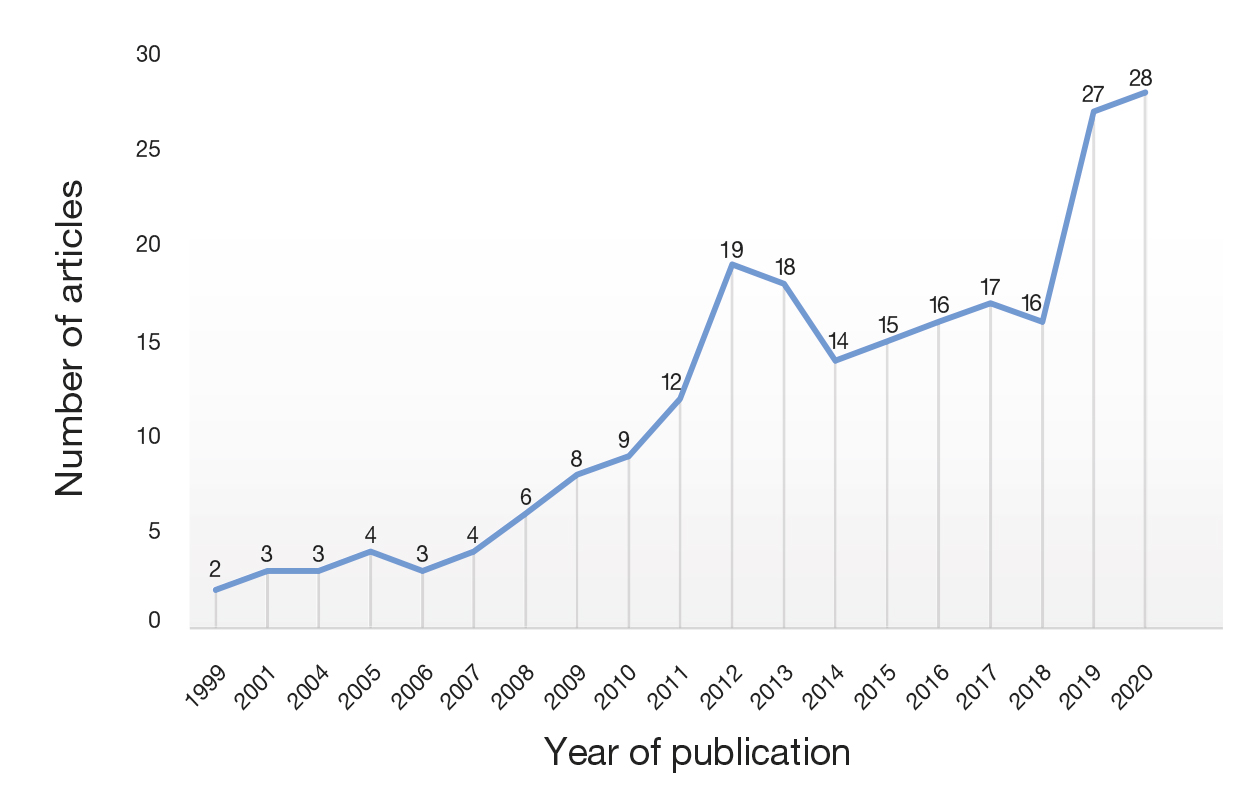

Since the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015, sustainability has become an indisputable factor in the organisation of sporting events. Historically, sustainability has been the subject of study by the scientific community. However, to date, there is no analysis of published research. The aim of this study was to analyse the way in which the sports sector has integrated sustainability into the organisation of sporting events, by means of a systematic review. The systematic review was conducted taking the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines as well as the risk-of-bias (RoB) assessment into consideration. The literature review was based on a consideration of 17 databases, covering the period from 1964 to 2020, with the string: sport, events, sustainability and sustainable. Initially 1,590 records were collected, of which a total of 224 were analysed in depth after the screening process was completed. One of the main findings is the identification of a steady increase in the number of publications over the whole period, with two peaks in 2012 and 2020. In terms of sustainability, the most studied aspect of this was environmental (41.5%), followed by social (32.1%), economic (17%) and the combination of the three (9.4%). The results obtained were reviewed in relation to the evolution of the sustainability milestones.

Introduction

On 25 September 2015, the United Nations (UN) Assembly established the guidelines for the development of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development by proposing 17 major Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 2030), comprising a total of 169 milestones and indicators. Through this proposal, the UN, based on the concept of sustainable development already defined in the Brundtland report in 1987 as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs, sought to lay the foundations for ending extreme poverty, fighting inequality and injustice, and combating climate change.

In recent years, sport has gained weight as an economic activity. The grey press estimates that sport contributed 3.3% of the EU’s GDP in 2021 and 3.6% of Spain’s GDP in 2021. Therefore, as an economic engine, sport is not exempted from the responsibility of being a sustainable activity, especially with regard to one of its main economic exponents, namely sporting events (Bácsné et al., 2021).

In the words of the same author, sporting events should not only be considered because of the impact they have, but also for the opportunity they provide to transmit values and principles, for their high visibility, for the impact they can have before and during the event, and also for the legacy they leave in the host community. According to Sánchez (2019), these can generate positive social, economic and environmental effects, as well as negative ones, disrupting the daily lives of many people living in the areas where sporting events take place. For this reason, the main international organisations in the field of sport, such as the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and some international federations, have been incorporating sustainability standards for organising international sporting competitions for some years now, thus promoting the involvement of the scientific community in the study of the benefits and results of these new standards (Bianchini & Rossi, 2021). In this sense, four main areas of study have been developed: i) elements required in strategic planning and attributes necessary to achieve sustainability in sporting events, determining which elements and/or attributes of the destination are necessary for successful and sustainable event organisation (Chersulich et al., 2020; Chen, 2022); ii) roles and impacts derived from sporting events as generators of sustainable sport tourism, identifying the role of the sport tourist and their impact on nature at the destination (Rivera, 2018; Ito & Hinch, 2020; Tadini et al., 2021); iii) the environmental sustainability of the sport tourism market, analysing the environmental impact on sport tourism and the contribution of sporting events (Ardoin et al., 2015; Mascarenhas et al., 2021); and iv) social impacts of mega-events, documenting the economic benefits that mega-events can generate (Chien et al., 2012; Mair & Smith, 2021). Alongside these are many other published studies linked in one way or another to the sustainability of sporting events. Therefore, taking into account the three fundamental pillars of sustainability considered in the development of sustainable sporting events (social, environmental and economic), the aim of this article is to carry out a systematic review of the publications to date on this subject, with the aim of understanding their evolution and scope for development.

Sporting events

The definition of the term is not a straightforward one and there are many authors who have contributed to shed light on the concept by looking at different elements in order to determine its taxonomy and classification.

Añó (2000) defines “sporting event” as a sporting activity that has a high level of social repercussion reflected in a strong media presence and that generates economic income in itself. Other authors consider sporting events as social, but also economic catalysts and promoters of the host city’s brand image (Dwyer & Fredline, 2008). Roche (2000), who focuses on defining ways to classify them, goes so far as to propose the grouping of sporting events according to the market or target audience, such as international events —Olympic Games or World Cups—, national events —national championships of any kind—, regional events —Pan American Games—, and local events —local championships of any kind—. In this sense, Graham et al. (2001) propose another classification according to the status of the organiser, for example national bodies, federations, clubs, associations, companies, educational institutions and others. Other authors such as Desbordes and Falgoux (2006) even make a classification according to the type of service offered by the organisation; they differentiate between events organised by public service providers, events organised by private providers, events of extraordinary scope that depend on a public entity with the support of private entities and events organised by an association. Finally, Müller (2015) develops a ranking framework based on four constitutive dimensions: i) visitor appeal, ii) media outreach, iii) cost, and iv) impact on infrastructure transformation. According to the number of attendees or costs generated by the events in the four dimensions, the author objectively assigns a weighting, which ultimately leads to the categorisation of events as giga-event, mega-event and big event.

Sustainability and dimensions

Of the many definitions of sustainability, most coincide that in order to be sustainable, economic growth policies and actions must respect the environment and also be socially equitable (Lein, 2017). Therefore, according to these authors, sustainability must be understood as an action-centred assumption that frames the conflict between environmental processes and social and economic connections.

Likewise, according to López et al. (2018), the concept of sustainable development must address social injustices if it is to achieve the fundamental principles set out in the Brundtland report, promoting the creation of practical means to reverse the environmental and socio-economic problems of today’s society in an integrative way. Taking into account reports and authors as diverse as the WCED (1987), the United Nations (2015), Takeuchi et al. (2016), among others, social, economic and environmental objectives must be intertwined in order for sustainable development to be achieved, as it is the result of the integration of the objectives of the three dimensions: economic, environmental and social.

In this regard, it should be noted that there are three principles set out in the Brundtland Report to be considered in the integrative implementation of a more sustainable set of actions: i) with regard to economic growth, this should take place in accordance with the capacity of ecosystems, to ensure that future generations have the same or a better quality of life; ii) the principle of social equity implies that the emphasis is placed on equity and social justice, the fair distribution of resources, both intragenerational and intergenerational, and iii) environmental protection is approached from a long-term perspective, ensuring that economic growth is consistent with the rate of consumption of natural resources and the degradation of ecosystems, avoiding, among other things, the collapse of the planet (WCED, 1987; United Nations, 2015; López et al., 2018).

The United Nations, together with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2001) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN, 2006), proposes that the three dimensions of sustainable development are interrelated on the basis of three principles or analytical categories, namely livability, equity and viability. Therefore, the three pillars should focus on profit, environmental care of the planet and social care of people’s well-being (Purvis et al., 2019).

Finally, it is worth highlighting some authors’ proposals for adding a fourth dimension to the three previous ones, the political-constitutional dimension. This dimension functions as a system of interactions within the indicators of each dimension and the interactions of the dimensions themselves (Inglés & Puig, 2015; Inglés et al., 2016).

Sports and sustainability

The relationship between sport and sustainable development is indisputable and heterogeneous, substantially transcending the widely contrasted purely environmental connotations (McCullough et al., 2020) which Domínguez et al. (2019) can cover aspects as varied as contributions to the development of basic skills such as teamwork and self-improvement, the eradication of gender barriers, the increase of equitable quality education or sport inclusivity, and the generation of alliances that contribute to the implementation of its principles.

Sustainability has established itself as a factor that is increasingly present in sport organisations, sporting events and actions linked to corporate social responsibility (McCullough et al., 2019). However, several authors indicate that recognition is not enough and more effort is required from stakeholders to promote sustainability in sport (McCullough & Cunningham, 2010). In this sense, nowadays, sustainability has been firmly established as one of the emerging scientific research topics in the field of sport management (Lis & Tomanek, 2020), generating a large area of interest for further development of scientific literature linked to the SDGs (Fonseca et al., 2022). In the same vein, it is worth mentioning the proposal by McCullough et al. (2020) for the recognition of a new sub-discipline within sport management, which has become known as sport ecology.

The scientific community has paid increasing attention to the relationship between sport and sustainability factors (Mallen, 2018), mainly because of the impact of sporting events on the destination region. Therefore, research on sporting events from a sustainability perspective is relevant, even though different literature reviews have followed contrasting approaches especially with regard to the relationship between sport organisations and sustainability (Mallen, 2018; Trendafilova & McCullough, 2018). In addition, the relationships between leisure activities and environmental sustainability have been investigated, setting aside the sport component (Vaugeois et al., 2017).

Sustainability can be incorporated at both the individual and institutional level, and has recently become a trend in the sporting event industry (Córdova et al., 2019). The term “sustainable” or “sustainability” has become a part of events’ guidelines or handbooks, specifically the policy aspect under which they operate and how they contribute to sustainability (Gulak-Lipka & Jagielski, 2020). However, despite the potential benefits, recently, some sporting event destinations have shown little interest in hosting sporting events (Mair & Smith, 2021). This situation is attributed to the lack of event hosts to strategically plan and efficiently capitalise on the potential benefits (O’Brien & Gardiner, 2006; Smith & Sparkes, 2019).

Taking into account the above context, the aim of this article was to identify the trends in scientific publications related to the sustainability of sporting events. This served to establish the question: where have we come from, and where are we now, from which further analysis can be made: where and how can/should we move forward?

Methodology

The methodology used for this research was the application of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines for systematic reviews (Moher et al., 2010; Urrutia & Bonfill, 2010), implementing a risk-of-bias (ROB) assessment system. A total of 17 databases were analysed: Ebscohost, SportDiscus, GreenFILE, Web of Science, Core Core Collection, CABI, Current Contents Connect, BIOSISCitation Index, BIOSIS Previews, MEDLINE, Zoological Record, KCI-Korean Journal Database, Derwent Innovations Index, SciELO Citation Index, Russian Science Citation Index, and Scopus. The search limit for published scientific articles was extended to December 2020.

The string was configured by combining the following words: “sport”, “events”, “sustainability” and “sustainable” (Table 1).

The initial collection of articles comprised 1,590 records. After discarding duplicates (n = 429), the title and abstract were screened (n = 835) using the Abstrackr programme (peer review). Once the articles were selected, they were read (n = 26) and a total of 102 articles were excluded. The reasons for the exclusion of articles were based on consideration of the following aspects: i) in relation to the event dimension, not specifying the event to which they referred —they referred to sporting events in general— or not including, within the dimension, strictly sporting events; and ii) with regard to the sustainability dimension, not including the study of sustainability as such. The Figure shows the database ultimately considered, which in this case, after the application of the different screening phases, consisted of a total of 224 articles.

In order to extract information from the articles, a categorisation table was drawn up based on the following dimensions: i) characterisation of the article: year of publication and identifier; ii) characteristics of the sporting event: origin —country and continent—, year or years in which it was held, event typology based on the proposal by Müller (2015) —giga, big and mega-event—, including the classification of regional/national events, not included by this author, and sport discipline —polysport or single-sport—, and iii) relationship with the areas of sustainability proposed by Purvis et al. (2019) —social, economic and environmental—, type of study —qualitative, quantitative or mixed—, type of methodology used —literature review, case study, survey, interview, questionnaire and others—, and subject matter —event database, residents, organisation, athletes, infrastructure, tourists, spectators, volunteers, experts and others—.

For a better understanding of the results, taking into account the trend in the number of articles published between 1964 and 2020, some of the results were analysed according to three main periods: 1964-1999, 2000-2014, and 2015-2020. The first period begins in 1964 with the hosting of the Tokyo Olympics up to 1999, when the IOC’s Agenda 21 was set, and marks the end of a period in which the concept of sustainability emerged as a challenge to be met by national, regional and local governments around the world. In the year 2000, the MDGs (8 goals related to human development) were established, implying the need to ensure environmental sustainability, especially in the Olympic Games within this period, up to 2014. The year 2015 marks the beginning of the final period, due to the development of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, up to 2020, when this systematic review will come to an end.

Results

Trend in the number of articles with respect to the years of publication

In the analysis of the results obtained in the study of the trend in the number of publications, it was possible to observe the existence of a constant and gradual increase over time in the number of publications, with the presence of two major peaks: 2012 and 2020, within the periods 2000-2014 and 2015-2020, respectively. It is also interesting to note that in 2012 the upward trend that began in 1999 was broken for the first time, and after two years the number of articles published began to rise again.

Characteristics of sporting events

Location

Of the 224 articles analysed, there was a clear predominance of events based on the European continent (37%), followed by the Asian continent (23.2%) (Figure 3).

When analysed according to periods and continents, it can be seen that the European continent had the highest concentration of events in the period 1964-1999 (44.2%) and in 2000-2014 (45.2%), with the Asian continent having the highest concentration in 2015-2020 (39.2 %) (Table 2).

Size

Following the classification made by Müller (2015), there was a clear predominance of giga-events (45.3%), followed by national/regional events (including those events not included in Muller’s category), accounting for 28.3%, and mega-events (17.8%). These results, analysed from the point of view of distribution according to periods, maintain this trend with nuances: a higher percentage of mega-events in all periods, although a higher proportion of national/regional events in the 2015-2020 period (Table 3).

Sport discipline

There was a clear predominance of the multisport discipline (63.4%), represented by the Olympic Games (90%). Of the single-sport events (36.6%), football (36.6%), athletics (12.2%), cycling (8.5%) and motor racing (7.3%) stand out, accounting for 64.6% of all single-sport events (Table 4).

Sustainability

Areas of study

The most recurrent study theme was environmental sustainability (41.5%), followed by social sustainability (32.1%). In this respect, it is worth noting the limited presence of articles focusing on economic sustainability. If the analysis is carried out according to distribution by time periods, the environmental area presents a higher concentration in the period 2000-2014 (46.6%), while in the period 2015-2020 it was the social area (37.3%) (Table 5).

Type of Study and Methodology

With regard to the study methodology, the results obtained demonstrated the presence of a clear predominance of qualitative studies in the three areas of sustainability: economic (75.1%), social (63.2%) and environmental (70.6%), with literature reviews being the most recurrent methodology in the study of the economic area (31.9%) and the social area (30.6%), followed by case studies in the environmental area (32.1%) (Table 6).

Object of study

The predominance of database use was observed in all areas: economic (73.3%), social (59.1%) and environmental (65.3%). Residents in the social area (15.2%) and event participants in the environmental area (8.7%) also stand out as the study objects with the highest occurrence after database use (Table 7).

Relationship between sporting events and areas of study

Regarding the relationship between event size and sustainability (areas of sustainability investigated in each event typology), giga-events stood out as the most studied in the three areas of sustainability: economic (10.2%), social (14.5%) and environmental (19.9%). The results of national/regional events are relevant, particularly in the social (11.4%), environmental (9.5%) and economic (7.8%) areas. (Figure 4)

If the trend in sustainability studies according to the type of sporting event is considered (Table 8), giga-events were the only type of event investigated in the period 1964-1999, occurring in the environmental field (43.8%). In the period 2000-2014 the trend of studying the environmental field continued (41.7%), as well as in the period 2015-2020 (34.8%).

In relation to mega-events, the most studied area was environmental (45.6%) in the period 2000-2014 and 2015-2020 (42.3%), the opposite applies to big events, where the most recurrent area of study is social, especially in recent years (54.5%). The national/regional category also stands out, where in the years 2000-2014 the predominant area of study was the environmental area (38.4%), which, in the final period, has shifted to the social field (47.5%).

Conclusions and discussion

Based on the number of articles published on the subject, it is clear that sustainability in sporting events has been a recurring theme over the last six decades, even though it was initially neither an economic nor a political priority for governments around the world. From this fact it can be inferred that the sports sector has been integrating, to a greater or lesser extent, the global sustainable development agenda in sporting events, a policy that can be observed through the constant and gradual increase in the number of articles published since 2006, with two key years identified: 2012 and 2020. The first, possibly linked to the London 2012 Olympic Games, considered by the IOC to be the greenest games in history. In this case, the Games were a milestone, not only because they successfully integrated the concept of sustainability from the very beginning of the Olympic project, designing a sustainable and environmentally friendly urban transformation strategy, known as the “London 2012 Sustainability Plan”, but also because of numerous innovative actions such as the construction of the first Olympic stadium built using surplus gas supply pipes, and the creation of the Olympic Park on polluted industrial land, turning it into the largest urban park in Europe, among others. And the second, probably linked to the implementation of the SDGs already proposed at the Sustainable Development Summit held in September 2015, reinforced in the first annual review of progress towards these goals in 2019 in the Sustainable Development Agenda organised by the UN.

On the other hand, considering international sporting events as a forum for expressing political positions (García Reyes, 2007) enables us to understand the trends regarding the organising continents. Thus, it can be observed that it is initially the European continent that upholds sustainability policy in the period 1964-2014, only to be relegated to second place by the Asian continent in the period 2015-2021. This is probably linked to the increase in the number of giga and mega sports venues on this continent, in the quest to be the world’s leading power, with one further avenue being sustainable sporting events.

Another aspect to highlight is the power of some sports organisations such as the IOC and how they act as a model and guide for other sports organisations. The IOC established the IOC Sport and Environment Commission in 1995, and amended the Olympic Charter in 1996, which led to the inclusion of sustainable strategies for the hosting of the Olympic Games. In 1999, the IOC introduced Agenda 21, with the main objective of actively engaging the Olympic movement (international federations and national Olympic committees) and the world of sport in sustainable development. This can be observed by looking at how, among the typologies of events analysed, the giga-events —Olympic Games and World Cups— were always the most studied events, regardless of the time, continent, discipline or type of sustainability considered.

A few years after the wake initiated by the IOC, the democratisation of sustainability can be regarded as arriving, or having arrived, mainly seeking to extend the awareness of sustainability to society at large. In other words, while initially in the period 1964-2014 it was giga-events that were studied the most, in the period 2015-2020 these were replaced by the study of more national and regional sporting events, which demonstrates the interest and dedication of resources to implement sustainable policies in smaller sporting events.

Likewise, and in relation to the study subject, the clear predominance of environmental issues over other subjects could be linked to the growing public concern about the effects of climate change that alert the public to the need to rethink the current production system, including, in the words of Schulenkorf (2012), the organisation and hosting of sporting events in all their magnitudes, highlighting the importance they can have when it comes to reducing the negative impact on the environment.

Finally, it should be noted that there is still a long way to go. This is a relatively recent field with no consensus on the definition of sustainability and, although there are studies, they are very heterogeneous and partial. For example, studies assessing sustainability by combining the three domains are in the minority, such as that of Varnajot (2020), which reveals the sustainable implications for communities hosting the Tour de France 2020 cycling race, or that of Kim et al. (2020), which investigates how local residents perceive the impact of the three areas of sustainability at the Pyeongchang 2018 Olympic Winter Games. It would be necessary to develop a model of analysis with an integral overall perspective, bearing in mind that in integrating these three areas they must be intertwined and dependent in order for a sporting event to be sustainable. It should take into account care for the planet and people’s social well-being, ensure greater equity in the social and economic dimemsions, prioritise social and environmental liveablity and environmental and economical viablity.

It can be determined that development towards the integration of sustainability in the organisation of sporting events has been steadily increasing since the emergence of the concept in the Brundtland report and its development in international sport organisations, such as the IOC, and has been integrated into the handbook on the organisation of sporting events in an undisputed way.

Limitations and future prospects

The main limitation of this study is the superficiality of the analysis of the publications identified.

With regard to future perspectives, it is recommended that the content of each research project be analysed in depth. This would allow progress to be made in identifying the development of analysis methodologies and whether or not there is a consensus on their use, as well as identifying analysis indicators and how to quantify the impact generated by sporting events.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the National Institute of Physical Education of Catalonia (INEFC) for its institutional and financial support.

References

[1] Añó Sanz, V. (2000). Organization of major international sporting events. Arbor, 165 (650), 265-287. https://doi.org/10.3989/arbor.2000.i650.969

[2] Ardoin, N., Wheaton, M., Bowers, A., Hunt, C., & Durham, W. (2015). Nature-based tourism’s impact on environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behavior: a review and analysis of the literature and potential future research. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(6), 838-858. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1024258

[3] Bácsné-Bába, É.; Ráthonyi, G.; Pfau, C.; Müller, A.; Szabados, G.N.; Harangi-Rákos, M. (2021). Sustainability-Sport-Physical Activity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 (4), 1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041455

[4] Bianchini, A., & Rossi, J. (2021). Design, implementation and assessment of a more sustainable model to manage plastic waste at sport events. Journal of Cleaner Production, 281, 12345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125345

[5] Chen, R. (2022). Effects of Deliberate Practice on Blended Learning Sustainability. Sustainability, 14 (3), 1785. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031785

[6] Chersulich, A., Perić, M., & Wise, N. (2020). Assessing and Considering the Wider Impacts of Sport-Tourism Events: A Research Agenda Review of Sustainability and Strategic Planning Elements. Sustainability, 12 (11), 4473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114473

[7] Chien, P. M., Richie, B. W., Shipway, R., & Henderson, H. (2012). I Am Having a Dilemma: Factors Affecting Resident Support of Event Development in the Community. Journal of Travel Research, 51(4), 451-463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287511426336

[8] Córdova, M. J., Calabuig, F., & Dos Santos, M. (2019). Key Determinants on Non-Governmental Organization’s Financial Sustainability: A Case Study that Examines 2018 FIFA Foundation Social Festival Selected Participants. Sustainability, 11(5), 1411. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051411

[9] Desbordes, M., & Falgoux, J. (2006). Management and organization of a sporting event. (Vol.609). Cerdanyola del Vallès: Inde.

[10] Domínguez, T., Garrido, P., & Vernet, B. (2019). Sport, integrity and sustainable development: The importance of integrity in sport in the 2030 Agenda. Encuentros Multidisciplinarios, 63, 1-9.

[11] Dwyer, L., & Fredline, L. (2008). Special Sport Events—Part I. Journal of Sport Management, 22 (4), 385–391. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.22.4.385

[12] Fonseca, I., Bernate, J., & Tuay, D. (2022). Corporate social responsibility and sporting events. A systematic review of scientific production. Sport TK-Revista Euroamericana de Ciencias del Deporte, 11, 8-8. https://doi.org/10.6018/sportk.470131

[13] García-Reyes, G. (2007). The Ollympic Games and the FIFA World Cup: Sport Tournaments or Political Instruments. CONfines de relaciones internacionales y ciencia política, 3(6), 83-94.

[14] Graham, S., Delpy Neirotti, L., & Goldblatt, J. (2001). The ultimate guide to sports marketing. (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies.

[15] Gulak-Lipka, P., & Jagielski, M. (2020). Incorporating sustainability into mega-event management as means of providing economic, social and environmental legacy: a comparative analysis. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 20 (388), 2859-2866. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2020.s5388

[16] Inglés, E., & Puig, N. (2015). Sports management in coastal protected areas. A case study on collaborative network governance towards sustainable development. Ocean & Coastal Management, 118, 178-188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.07.018

[17] Inglés, E., Funollet, F., & Olivera, J. (2016). Physical activities in the natural environment. Present and future. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 124, 49-52. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.cat.(2016/2).124.05

[18] Ito, E., & Hinch, T. (2020). A systematic review of sport tourism research in Japan 1. Tourism Development in Japan, 1, 82-101. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429273513-5

[19] IUCN. (2006). The Future of Sustainability Re-thinking Environment and Development in the Twenty-first Century.

[20] Kim, M., Park, S., & Kim, S. (2020). The perceived impact of hosting mega-sports events in a developing region: the case of the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympic Games. Current Issues in Tourism, 24 (20), 2843-2848. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1850652

[21] Lein, J. K. (2017). Futures Research and Environmental Sustainability: Theory and Method. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis.

[22] Lis, A., & Tomanek, M. (2020). Sport Management: Thematic Mapping of the Research Field. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 20 (168), 1201-1208. doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2020.s2167

[23] López, M., Virto, N., Manzano, J., & Madariaga, J. (2018). Residents’ attitude as determinant of tourism sustainability: The case of Trujillo. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 35, 36-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.02.002

[24] Mair, J., & Smith, A. (2021). Events and sustainability: why making events more sustainable is not enough. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(11–12), 1739-1755. doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1942480

[25] Mallen, C. (2018). Robustness of the sport and environmental sustainability literature and where to go from here. Routledge handbook of sport and the environment, 11-35.

[26] Mascarenhas, M., Pereira, E., Rosado, A., & Martins, R. (2021). How has science highlighted sports tourism in recent investigation on sports’ environmental sustainability? A systematic review. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 25(1), 42–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2021.1883461

[27] McCullough, B. P. & Cunningham, G. B. (2010). A Conceptual Model to Understand the Impetus to Engage in and the Expected Organizational Outcomes of Green Initiatives. Quest, 62 (4), 348-363. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2010.10483654

[28] McCullough, B. P., Orr, M. & Kellison, T. (2020). Sport Ecology: Conceptualizing an Emerging Subdiscipline Within Sport Management. Journal of Sport Management, 34 (6), 509-520. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0294

[29] McCullough, B. P., Orr, M. & Watanabe, N. M. (2019). Measuring Externalities: The Imperative Next Step to Sustainability Assessment in Sport. Journal of Sport Management, 34 (5), 393-402. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0254

[30] Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2010). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement (Chinese edition). International Journal of Surgery, 8(5), 336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007

[31] Müller, M. (2015). What makes an event a mega-event? Definitions and sizes. Leisure Studies, 34(6), 627–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2014.993333

[32] O’Brien, D., & Gardiner, S. (2006). Creating Sustainable Mega Event Impacts: Networking and Relationship Development through Pre-Event Training. Sport Management Review, 9(1), 25-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1441-3523(06)70018-3

[33] OCDE. (2001). Sustainable Development: Critical Issues. Paris: OECD Publishing.

[34] ONU. (2015). Resolución A/RES/70/1 Transformar nuestro mundo: la agenda 2030 para el desarrollo sostenible. New York, USA.

[35] Purvis, B., Mao, Y., & Robinson, D. (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustain Sci, 14, 681-695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5

[36] Rivera Mateos, M. (2018). Active tourism, outdoor recreation and nature sports: a geographical reading. Bulletin Of the Association of Spanish Geographers, (77), 462-492. https://doi.org/10.21138/bage.2548

[37] Roche, M. (2000) Mega-events and modernity: Olympics and expos in the growth of global culture. (2001b). Choice Reviews Online, 38(11), 39-6250.

[38] Sánchez-Sáez., J. (2019). Sports events as a local development instrument. Culture, science and sport, 14(41), 91-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.12800/ccd.v14i41.1268

[39] Schulenkorf, N., & Edwards, D. (2012). Maximizing Positive Social Impacts: Strategies for Sustaining and Leveraging the Benefits of Intercommunity Sport Events in Divided Societies. Journal of Sport Management, 26 (5), 379–390. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.26.5.379

[40] Smith, B., & Sparkes, A. C. (2019). Disability, sport, and physical activity. Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies, 2, 391–403. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203144114-34

[41] Tadini, R., Gauna, C., Gandara, J., & Sacramento, E. (2021). Sporting events and tourism: systematic review of the literature. Tourism Research, 21(2), 22–45. https://doi.org/10.14198/INTURI2021.21.2

[42] Takeuchi, K., Allenby, B., & Elmqvist, T. (2016). Call for paper for sustainability science and implementing the sustainable development goals. Sustain Sci, 11, 177–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0353-9

[43] Trendafilova, S., & McCullough, B. (2018). Environmental sustainability scholarship and the efforts of the sport sector: A rapid review of literature. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1), 1467256.https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1467256

[44] Varnajot, A. (2020). The making of the Tour de France cycling race as a tourist attraction. World Leisure Journal, 62(3), 272–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2020.1798054

[45] Vaugeois, N., Parker, P., & Yang, Y. (2017). Is leisure research contributing to sustainability? A systematic review of the literature. Leisure/Loisir, 41(3), 297–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2017.1360151

[46] WECD. (1987). Report of the world commission on environment and development: our common future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: September 21, 2022

Accepted: January 19, 2023

Published: July 1, 2023

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en