Relationship Between Possession Initiation Type and Offensive Effectiveness in UEFA Euro 2020 Football: An Observational Study

*Corresponding author: Rubén Maneiro rubenmaneirodios@gmail.com

Cite this article

Maneiro, R., Arroyo-del Bosque, R., Amatria-Jiménez, M., & Iván-Baragaño, I. (2025). Relationship between possession initiation type and offensive effectiveness in UEFA Euro 2020 football: An observational study. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 162, 53-64. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2025/4).162.06

Abstract

Although research in high-performance football has extensively addressed the offensive phase, specific analysis on the relationship between initiation of possession and offensive effectiveness remains limited. Within the framework of observational methodology, 2,324 offensive sequences in elite football were recorded and analyzed. Three objectives were established for the present study: at the univariate level, to describe the most common patterns in ball recovery and possession initiation; at the bivariate level, to identify statistically significant relationships between the type of recovery and the other variables considered; and at the multivariate level, to develop a classification model that explains the interaction between key dimensions. The results showed that ball recovery through transition occurs in 58% of cases, mainly in the team’s own field (61.5%), and that teams tend to progress quickly (81%) after regaining possession. The bivariate analysis confirmed that recoveries in transition favor direct attacks, and that recoveries after set pieces allow for a better defensive organization of the opponent. The duration of possession is shorter when the recovery is in transition compared to recoveries after set pieces. The decision tree model reinforced these findings and highlighted the influence of the type of recovery through transition. In conclusion, these findings may have direct application in high-performance football, providing key information to optimize offensive tactics and maximize the likelihood of success.

Introduction

Football research has experienced a huge growth in recent years. According to the PubMed database, and entering the topics “soccer” and “football”, 2,450 scientific studies have been published in the decade 2015-2025 alone. This figure reflects the strong expansion of research into the sport from different areas such as physiology, psychology and tactics (Rein & Memmert, 2016; Goes et al., 2021).

In relation to the latter, and more specifically to the offensive process, this has been the subject of considerable attention in the scientific literature in recent years (Baert & Amez, 2018; Fernández-Navarro et al., 2018; Kempe & Memmert, 2018; Wilson et al., 2020; Mitrotasios et al., 2019; Sarmento et al., 2018). These studies have provided advanced analytical tools that facilitate the identification of tactics from the build-up phase through to the completion of attacking plays.

Within this framework, several studies have examined the key factors influencing offensive play. One of the most studied aspects is ball possession, which is considered a key indicator of attacking dynamics (Jones et al., 2004; Lago-Peñas & Martín-Acero, 2007). The contexts of interaction (Castellano et al., 2013) are also key aspects.

In terms of offensive playing styles, studies such as those by Hewitt et al. (2016) and Lago-Peñas et al. (2017) have analyzed the effectiveness of different attacking strategies, including counter-attacking, direct attack and combination attack in the context of high-performance football. Complementarily, the generation of goal opportunities and associated behavioral patterns has been extensively analyzed in the literature (Amatria et al., 2019; Tenga et al., 2010; Wright et al., 2011).

While these studies have increased our understanding of offensive mechanisms in football, there are still unresolved questions. A critical aspect is how possession is regained to initiate an attack. Previous research has analyzed the location of recovery (Barreira et al., 2014a), the specific zones of the field where it occurs (Barreira et al., 2014b; Espada et al., 2018) and the defensive systems employed for this purpose (Toda et al., 2022). However, there is little research (Iván-Baragaño et al., 2021) that has addressed the comparison between different methods of recovery, such as direct ball stealing (change between possession and non-possession roles) versus set pieces resulting from rule infringements (e.g. throw-ins, fouls, and restarts following a shot on goal, among others). This question still represents a gap in the scientific literature.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was threefold: at a univariate level, to characterize and describe the usual practices of attacking mechanisms in football according to different dimensions of interest; at a bivariate level, accompanied by a chi-squared contrast, to find out the possible statistically significant relationships between the dimensions considered and the way of recovering the ball; finally, at a multivariate level, to develop a classification model to explore the interaction between dimensions associated with the type of initiation of ball possessions.

Method

For the development of this work, the observational methodology (Anguera, 1979) was used, which has proven to be one of the most appropriate for the study of spontaneous interaction behavior among athletes, also from its mixed methods aspect (Anguera et al., 2014; Anguera & Hernández-Mendo, 2016).

Design

The design of this research was nomothetic, as a plurality of units were analyzed; in terms of temporality, a cross-sectional design was chosen, as a specific competition was analyzed; and finally, multidimensional, due to the multiple levels of response (Anguera et al., 2011). It is worth noting that the observation process adhered to scientific rigor criteria, with complete observer awareness.

Participants

A purposive observational or convenience sampling method was used to select participants (Anguera et al., 2011). Ball possessions were collected and analyzed during the final phase of the UEFA EURO 2020 tournament. In total, 2,324 attacks were examined, corresponding to the round of 16, the quarter-finals, the semi-finals, and the final. The inclusion criteria were as follows: the offensive action was recorded from the moment possession changed from one team to the other or a regulation stoppage occurred. In addition, it was considered possession when any of the following conditions were met: a duration of possession equal to or longer than 4 seconds; when the player recovered the ball and made a pass; when the player made three consecutive touches on the ball without passing, provided the possession lasted 4 seconds or more, or when a shot was taken. The data collection was carried out through public images broadcast on television (Mediaset channel), a general-interest broadcaster sponsored by various private entities.

Observational Instrument

The observational instrument proposed by Maneiro et al. (2020) was used for this study (see Table 1), due to its good fit when analyzing the offensive phase in football (Maneiro et al., 2023). In addition, the instrument contributes to the satisfaction of the pre-set objectives. The observational instrument is a combination of field format and category systems (Anguera et al., 2007). Dimensions and subdimensions collated in previous work have been included, such as the following: context of interaction (Castellano, 2008), intention (Maneiro et al., 2019), partial result (Lago, 2009), period of the game (Jones et al., 2004).

Registration and Coding

Data Quality

Data recording (Hernández-Mendo et al., 2014), as well as the concordance analysis, was carried out using Lince Plus software (Soto et al., 2019). Four observers were selected for data collection, all of whom held PhDs in Sports Sciences and were UEFA PRO licensed coaches. The inter-observer agreement analysis was performed on a pairwise basis. The six possible combinations between the four observers (Ob1-Ob2, Ob1-Ob3, Ob1-Ob4, Ob2-Ob3, Ob2-Ob4 and Ob3-Ob4) were carried out, and an average Kappa value of .92 was obtained, which according to the scale by Fleiss et al. (2003) can be considered very good.

Prior to the coding process, eight training sessions were carried out, following Anguera et al. (1999). The training sessions lasted 2 hours each. The first three sessions were conducted as a group with the selected observers. The study was presented to them theoretically, the behaviors to be observed in players were defined, the observational instrument was presented to them, and they were trained in the use of the Lince Plus recording tool. The fourth session involved the observers in the observation and recording of 20 offensive actions previously selected by the principal investigator, ordered from least to most complex. After recording the actions, the discrepancies found were discussed. The fifth and sixth sessions were conducted individually with each observer. The recorded actions were initially outlined by the lead researcher, and the observers were trained on how to record the actions. The last two training sessions were also conducted individually and Cohen’s Kappa coefficient of concordance between the principal investigator and each observer was checked. Ten percent of the total sample (n = 233) was used to measure data quality.

The data obtained were Type IV, that is, time-based concurrent data (Bakeman, 1978). This is due to the fact that there are co-occurrences of players’ behaviors.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS Statistics 25 was used to carry out the analyses. Firstly, in order to characterize and describe the usual practices of the offensive process, a univariate or descriptive analysis was conducted. Next, in order to identify possible statistically significant relationships between the dimensions considered and the type of ball recovery, a bivariate analysis was conducted using a chi-square test. Finally, a multivariate analysis was carried out, based on the decision tree technique (Rokach & Maimon, 2005), with the aim of developing a classification model that allows us to understand the interaction of the dimensions associated with the initiation of ball possessions.

Results

In the total number of matches belonging to the round of 16, quarter-finals, semi-finals and final, a total of 2,324 attacks were carried out, which is an average of 72 attacks per team/match (Table 2). The low level of attacking success (goal, shot or delivery into the box) stands out, as only 2% of possessions ended in a goal, 12% in a shot, 21% in a delivery into the box and 65% ended unsuccessfully. It is also noteworthy that the teams took possession in their own field (61.5%), that they made fewer than 7 passes, and that they had the will to attack (81.4%).

Results of the Bivariate Chi-Squared Test

In order to find out the relationship between the dimension “initiation type” and the other dimensions considered, a contingency table with a chi-squared test was used to compare the degree of effectiveness achieved according to the different dimensions included in the observation instrument. (Table 3)

Table 3

Results at the bivariate level, using the “initiation type” dimension as the reference

Results of the Decision Tree Analysis

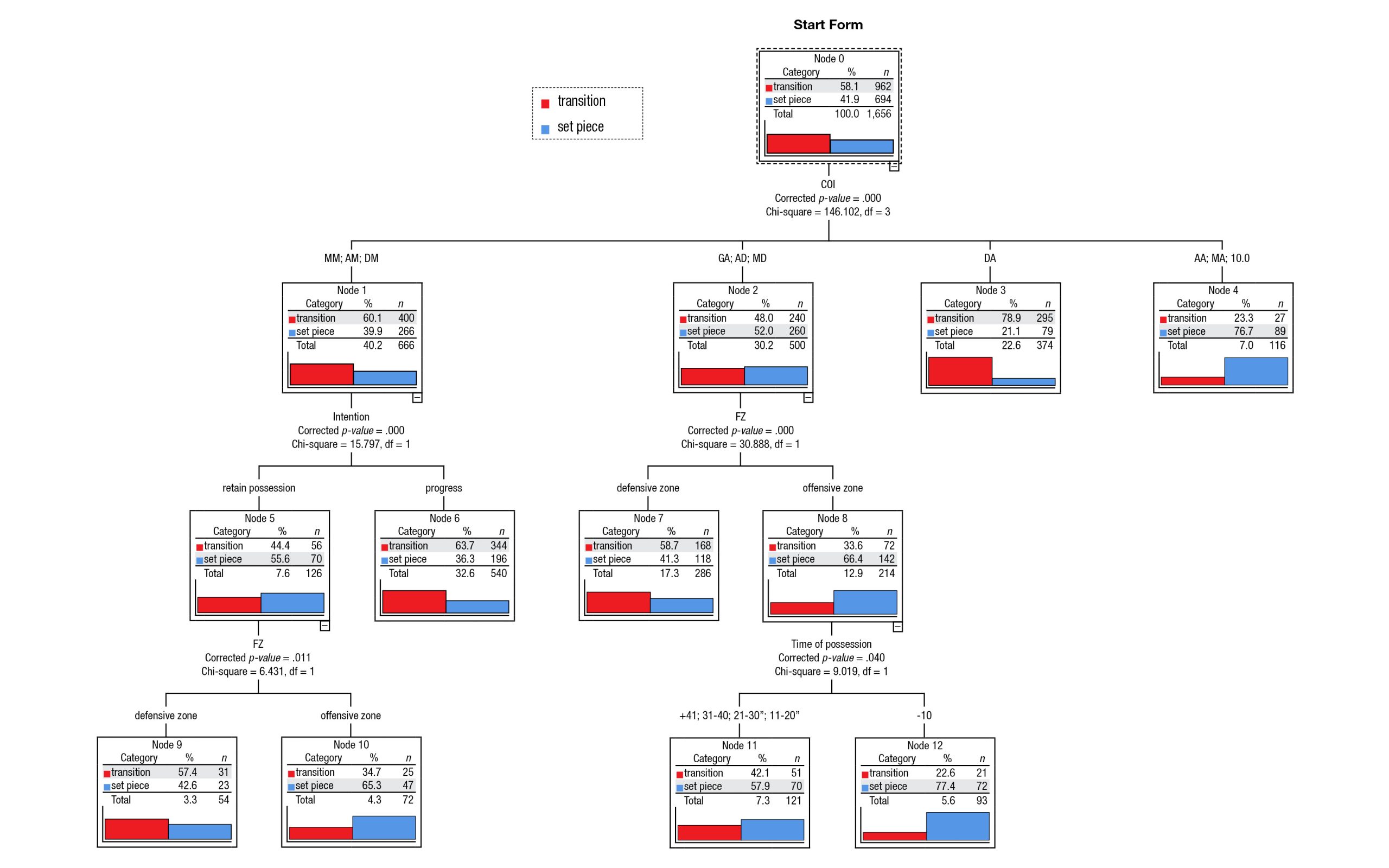

The results of the decision tree based on the CHAID algorithm are presented in Figure 1. This model comprised 13 nodes, of which 8 were terminal. The theoretical results of the model are presented in Table 4.

To carry out the validation process, the total sample of possessions (2,324) was divided into a training set (70%) and a test set (30%).

The model’s predictive dimensions are shown in Table 5, titled Classification of the Model. In this way, the evaluation of the effectiveness of the model’s performance can be observed. The results in Table 5 indicate that the model correctly classified 64.5% of the sample. Specifically, for each subdimension of the dependent variable, the highest accuracy was found in the “transition” category, at 87.1% (with a specificity of 87.1% and a sensitivity of 40.1%).

The model shows a predictive risk of .326 (32.6%) in the training set, with a standard error of 0.012. In the contrast (validation) phase, the risk increases slightly to .355 (35.5%), with a standard error of 0.019. This indicates that the model has a moderate error rate, with acceptable performance in both training and validation. Although there is a slight increase in error during the test phase, it appears to be relatively stable, indicating that the model generalizes well without excessive overfitting.

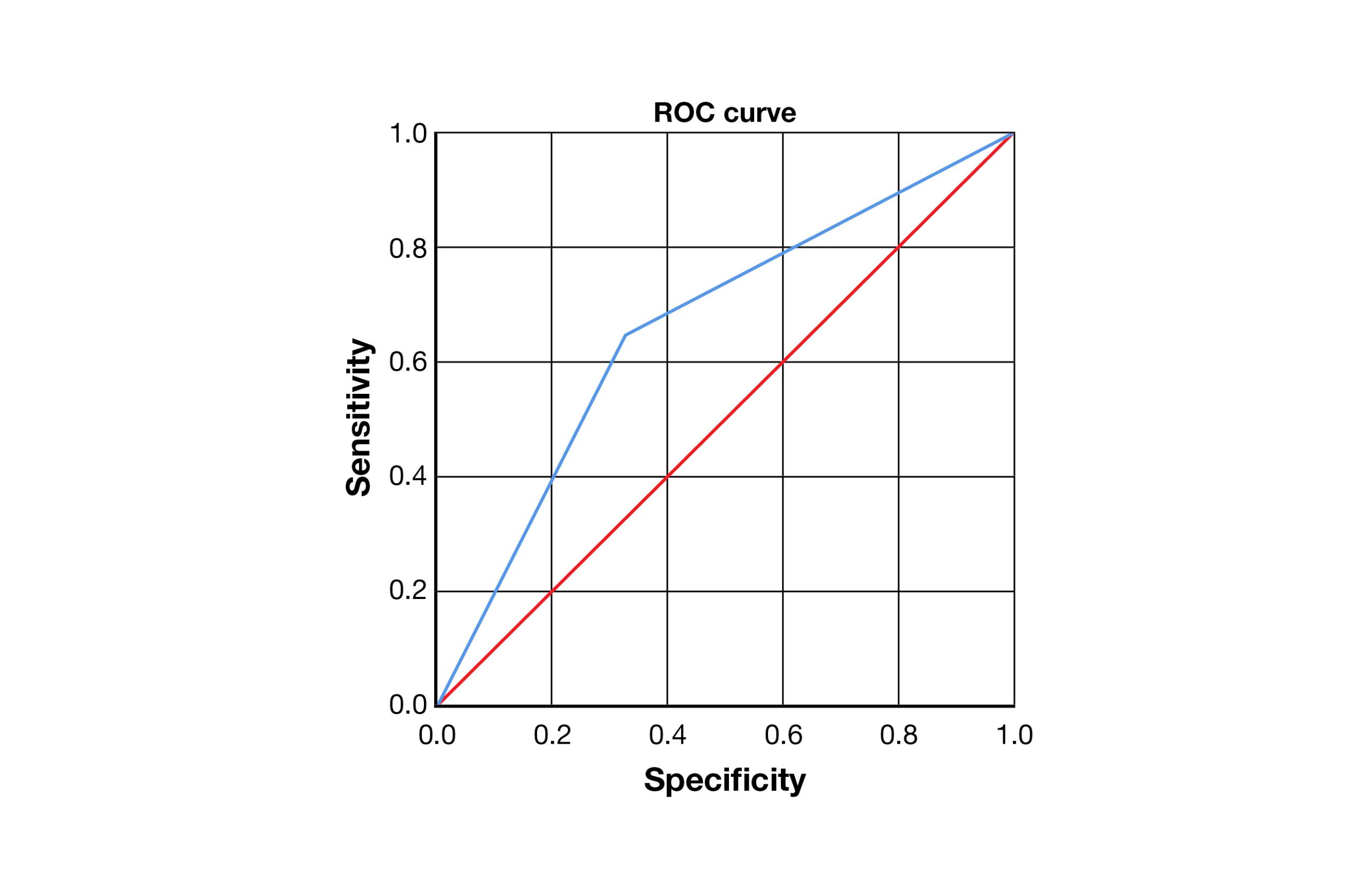

Finally, the performance of the model was assessed using the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) (Figure 2). The ROC curve is a graphical representation that evaluates the performance of a binary classification model by showing the relationship between the true positive rate (sensitivity) and the false positive rate (1 – specificity) across different decision thresholds. Its main metric is the AUC (Area Under the Curve), which indicates the model’s ability to distinguish between classes. In this case, it yielded a value of .66, meaning the model has a 66% chance of correctly ranking a positive case above a negative one. This suggests a good performance—better than random (.50)—but still far from optimal (1).

Discussion

This study had three main aims: at the univariate level, to describe the most common patterns of the offensive process; at a bivariate level, to determine the possible statistically significant relationships between the dimensions considered and the type of ball recovery; and finally, at a multivariate level, to develop a classification model to determine the interaction of the dimensions associated with the initiation of ball possessions.

At the univariate level, it was observed that teams recovered the ball through transition in 58% of the cases, mainly in their own field (61.5%), with the score tied (64%), and in the midfield line of the observed team against the midfield line of the opponent (37%). Furthermore, the initial intention of the team that recovers the ball was to progress forward 81% of the time. These results represent a first approximation to the characterization of this type of actions and coincide with previous research, such as the study by Oberstone (2011), which highlights a higher frequency of recoveries in transition. They are also in line with the findings of Tenga and Sigmundstad (2011) regarding the prevalence of own-field recoveries and with the work of Barreira et al. (2014a) on behaviors following ball recovery.

At the bivariate level, we proceeded to analyze the relationship between the dimension “initiation type” and the other dimensions included in the observation instrument. The results reveal interesting relationships. Firstly, when they regain the ball through transition, the tactical behavior of the teams is to progress and advance towards the opponent’s goal, a fact that is in line with that proposed by Barreira et al. (2014b) and Casal et al. (2019). These authors found that the behavior of progressing is directly associated with successful teams or those leading on the scoreboard, although other authors relate it to playing style (Lago-Peñas & Dellal, 2010).

As far as the time of possession is concerned, the results are conclusive and directly related to the previous paragraph: the ball possessions of teams that recover the ball through a steal in the opponent’s field are significantly shorter than those of teams that recover the ball by set pieces. At this point, it is very likely that offensive transitions (Eusebio et al., 2025), and direct attack or counter-attack (Lago-Peñas et al., 2017) will become relevant. When the ball is recovered from a set piece (throw-in, free kick…), the opposing team has time to strategically retreat. In contrast, when possession is regained through transition, numerous spaces emerge that the recovering team can exploit to progress.

Interesting results are also found in the ball recovery zone. While teams that recover the ball through a steal tend to do so in their own field or defensive zone, those that recover it through a set piece typically do so in the offensive zone. In the first case, the defensive density of the team out of possession favors recovery through transition or a steal, whereas recovery in the offensive sector via set pieces may stem from pressing actions by the defending team, which hasten the opponent’s decision-making and can thus lead to more turnovers. More specifically, the throw-in appears to be the set piece action that gains the most relevance, according to Barreira et al. (2014a), who found that the best teams tend to win the ball back in this way, following pressure actions and harassment of the opponent, inducing errors (Vogelbein et al., 2014).

When analyzing which line recovers the ball against which opposing line based on the interaction context, it is observed that the defensive line tends to recover the ball through steals against the opponent’s advanced and midfield lines. On the other hand, when the midfield line is the one recovering the ball, it typically does so through set-piece actions. One possible explanation is that defenders possess more specialized technical and tactical skills for executing steals, supported by defensive structures specifically trained for this purpose. In contrast, the midfield line has a more versatile profile, capable of balancing offensive and defensive roles and adapting its resources to the demands of the game and the characteristics of the opponent.

In this context, the study by Castellano et al. (2013) analyzed the use of space in football and highlighted the importance of spatial relationships among players of both teams. The authors noted that opportunities for action arise from the complementarity of relationships between players, implying that the positioning and spatial interactions between defensive and attacking lines are fundamental to understanding ball recovery dynamics.

In addition, previous research has found that recovering the ball in midfield zones increases attacking efficiency. For example, Barreira et al. (2014b) found that interceptions in the central midfield-offensive zone resulted in ineffective attacks, while goalkeeper interventions in the central defensive zone did not show significant relationships with end-of-attack inducing behaviors.

The behavior of the partial score depending on how the ball is recovered is also particularly noteworthy. Teams that are winning recover the ball twice as often through a steal than through a set-piece situation. Fernandes et al. (2020) claim that worse teams are less likely to recover the ball through a steal or interception. In contrast, Barrreira et al. (2014b) state that attacking patterns are directly influenced by the way in which the ball is recovered. Therefore, it is possible to think that, in order to optimize the attack once the ball has been recovered and to take advantage of the moments of disorder of the opposing team to adjust to the role change (from ball possessor to non-possessor), teams that are winning opt to recover the ball in transition.

Finally, at the multivariate level, the decision tree model reinforces the previous results, and highlights which lines of interaction initiate ball possession. Once again, the dimension that provides the greatest information gain is the interaction context, confirming that the more defensive or deeper the recovering line is (defensive or midfield line), the more likely it is to regain possession through a steal during transition. In contrast, the more advanced the line (advanced line), the more likely it is to recover the ball through a set-piece situation. Moreover, when ball recovery occurs through a steal, teams tend to progress immediately into attack, aiming to capitalize on the role transition moment to maximize their chances of offensive success. In other words, it can be concluded that recovering the ball through a transitional steal fosters or increases offensive opportunities to advance into the opposition half.

Conclusions

The present study aimed to explore in depth the relationship between the type of possession initiation and its offensive effectiveness. For this purpose, the “initiation type” dimension was used as a reference point. The main conclusions of the present study can be summarized in four points: 1) At the univariate level, teams that recover the ball through a transition tend to advance quickly into attack compared to when they regain possession through a set piece; 2) At the bivariate level, fast attacks following a steal are associated with shorter possessions and opportunities for direct play or counterattacks, whereas recoveries through set pieces favor a more elaborate build-up; 3) At the multivariate level, ball recovery in defensive zones occurs mostly through transitions, while in offensive zones it is more frequently associated with set-piece situations; defensive and midfield lines are more likely to recover the ball in transition, whereas advanced lines tend to do so through set pieces.

Practical Applications

Based on the conclusions of the present study, several practical applications can be drawn for coaches at youth, amateur, and elite levels of football: encouraging specific training sessions to take advantage of offensive transitions after ball recovery, such as drills focused on decision-making at speed and rapid finishing; and developing strategies to maximize pressing and force turnovers from the opponent, while optimizing the execution of set-piece actions. In addition, from the perspective of opponent analysis, it is advisable to identify the opposing team’s ball recovery patterns in order to design effective pressing and recovery strategies.

Limitations

Some of the possible limitations of the present study include: the degree to which the results can be generalized, as they refer to a single specific tournament; the extrapolation to women’s football, since the study focuses solely on men’s football; and, finally, the influence of other dimensions or subdimensions not considered, which may affect the type of possession initiation.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Spanish Government project LINCE PLUS: Multimodal platform for data integration, synchronization and analysis in physical activity and sport [PID2024-15605NB-l00] (2025-2027) (Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, Agencia Estatal de Investigación y Unión Europea).

References

[1] Amatria, M., Maneiro, R., & Anguera, M. T. (2019). Analysis of successful offensive play patterns by the Spanish soccer team. Journal of Human Kinetics, 69(1), 191–200. doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2019-0011

[2] Anguera, M. T., & Hernández-Mendo, A. (2016). Avances en estudios observacionales de Ciencias del Deporte desde los mixed methods. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 16(1), 17–30.

[3] Anguera, M.T. (1979). Observational typology. Quality and Quantity, 13(6), 449–484. doi.org/10.1007/BF00222999

[4] Anguera, M.T., Blanco-Villaseñor, A., Hernández-Mendo, A., & Losada, J.L. (2011). Diseños observacionales: ajuste y aplicación en psicología del Deporte. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 11(2), 63–76.

[5] Anguera, M.T., Blanco-Villaseñor, A., Losada, J.L., & Sánchez-Algarra, P. (1999). Análisis de la competencia en la selección de observadores. Metodología de las Ciencias del Comportamiento, 1(1), 95–114.

[6] Anguera, M.T., Camerino, O., Castañer, M., & Sánchez-Algarra, P. (2014). Mixed methods en la investigación de la actividad física y el deporte. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 23(1), 123–130.

[7] Anguera, M.T., Magnusson, M.S., & Jonsson, G.K. (2007). Instrumentos no estándar: planteamiento, desarrollo y posibilidades. Avances en Medición, 5(1), 63–82.

[8] Baert, S., & Amez, S. (2018). No better moment to score a goal than just before half time? A soccer myth statistically tested. Plos One, 13(3), e0194255. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194255

[9] Bakeman, R. (1978). Untangling streams of behavior: Sequential analysis of observation data. In G.P. Sackett (Ed.), Observing behaviour, Vol. II: Data collection and analysis methods (pp. 63–78). University Park Press.

[10] Barreira, D., Garganta, J., Guimaraes, P., Machado, J., & Anguera, M. T. (2014a). Ball recovery patterns as a performance indicator in elite soccer. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part P: Journal of Sports Engineering and Technology, 228(1), 61–72. doi.org/10.1177/1754337113493083

[11] Barreira, D., Garganta, J., Machado, J., & Anguera, M. T. (2014b). Effects of ball recovery on top-level soccer attacking patterns of play. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria y Desempenho Humano, 16, 36–46. doi.org/10.5007/1980-0037.2014v16n1p36

[12] Casal, C. A., Anguera, M. T., Maneiro, R., & Losada, J. L. (2019). Possession in football: More than a quantitative aspect–a mixed method study. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 501. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00501

[13] Castellano, J. (2008). Análisis de las posesiones de balón en fútbol: frecuencia, duración y transición. Motricidad. European Journal of Human Movement, 21, 189–207.

[14] Castellano, J., Álvarez Pastor, D., & Blanco-Villaseñor, Á. (2013). Análisis del espacio de interacción en fútbol. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 22(2), 0437–446.

[15] Espada, M., Fernandes, C., Martins, C., Leitao, H., Figueiredo, T., & Santos, F. (2018). Goal characterization after ball recovery in players of both genders of first league soccer teams in Portugal. Human Movement Special Issues, 2018(5), 73–81. doi.org/10.5114/hm.2018.81288

[16] Eusebio, P., Prieto-González, P., & Marcelino, R. (2025). Unlocking dynamics of goal-scoring: the showdown between direct and indirect transition goals across football leagues. Biology of Sport, 42(2), 113–123. doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2025.142640

[17] Fernandes, T., Camerino, O., Garganta, J., Hileno, R., & Barreira, D. (2020). How do elite soccer teams perform to ball recovery? Effects of tactical modelling and contextual variables on the defensive patterns of play. Journal of Human kinetics, 73, 165.

[18] Fernandez-Navarro, J., Fradua, L., Zubillaga, A., & McRobert, A. P. (2018). Influence of contextuales variables on styles of play in soccer. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 18(3), 423–436. doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2018.1479925

[19] Fleiss, J.L., Levin, B., & Paik, M.C. (2003). Statistical methods for rates and proportions. Wiley (Ed.). 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi.org/10.1002/0471445428

[20] Goes, F. R., Kempe, M., Meerhoff, L. A., Lemmink, K. A. P. M., & Brink, M. S. (2021). Unlocking the potential of big data to support tactical performance analysis in professional soccer: A systematic review. European Journal of Sport Science, 21(9), 1225–1241. doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2020.1747552

[21] Hernández-Mendo, A. Castellano, J., Camerino, O., Jonsson, G., Villaseñor, Á. B., Lopes, A., & Anguera, M. T. (2014). Programas informáticos de registro, control de calidad del dato, y análisis de datos. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 23(1), 111–121.

[22] Hewitt, A., Greenham, G., & Norton, K. (2016). Game style in soccer: what is it and can we quantify it?. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 16(1), 355–372. doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2016.11868892

[23] Iván-Baragaño, I., Maneiro, R., Losada, J. L., & Ardá, A. (2021). Multivariate analysis of the offensive phase in high-performance women’s soccer: a mixed methods study. Sustainability, 13(11), 6379. doi.org/10.3390/su13116379

[24] Jones, P. D., James, N., & Mellalieu, S. D. (2004). Possession as a performance indicator in soccer. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 4(1), 98–102. doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2004.11868295

[25] Kempe, M., & Memmert, D. (2018). “Good, better, creative”: the influence of creativity on goal scoring in elite soccer. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(21), 2419–2423. doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1459153

[26] Lago, C. (2009). The influence of match location, quality of opposition, and match status on possession strategies in professional association football. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27(13), 1463–1469. doi.org/10.1080/02640410903131681

[27] Lago-Peñas, C. & Dellal, A. (2010). Ball possession strategies in elite soccer according to the evolution of the match-score: the influence of situational variables. Journal of Human Kinetics, 25, 93–100. doi.org/10.2478/v10078-010-0036-z

[28] Lago-Peñas, C., & Martín-Acero, R. (2007). Determinants of possession of the ball in soccer. Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(9), 969–974. doi.org/10.1080/02640410600944626

[29] Lago-Peñas, C., Gómez-Ruano, M., & Yang, G. (2017). Styles of play in professional soccer: an approach of the Chinese Soccer Super League. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 17(6), 1073–1084. doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2018.1431857

[30] Maneiro, R., Casal, C. A., Álvarez, I., Moral, J. E., López, S., Ardá, A., y Losada, J. L. (2019). Offensive Transitions in High-Performance Football: Differences Between UEFA Euro 2008 and UEFA Euro 2016. Frontiers in Psychology. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01230

[31] Maneiro, R., Losada, J. L., Ardá, A., & Iván-Baragaño, I. (2023). Proposal of a predictive model for the attack in women’s football depending on the part of the match. Kinesiology, 55(1), 30–37. doi.org/10.26582/k.55.1.4

[32] Maneiro, R., Losada, J.L., Casal, C.A., & Ardá, A. (2020). The influence of match status on ball possession in high performance women’s football. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 487. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00487

[33] Mitrotasios, M., Gonzalez-Rodenas, J., Armatas, V., & Aranda, R. (2019). The creation of goal scoring opportunities in professional soccer. tactical differences between spanish la liga, english premier league, german bundesliga and italian serie A. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 19(3), 452–465. doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2019.1618568

[34] Oberstone, J. (2011). Comparing team performance of the English premier league, Serie A, and La Liga for the 2008-2009 season. Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports, 7(1). doi.org/10.2202/1559-0410.1280

[35] Rein, R., & Memmert, D. (2016). Big data and tactical analysis in elite soccer: future challenges and opportunities for sports science. SpringerPlus, 5(1), 1410. doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-3108-2

[36] Rokach, L., & Maimon, O. (2005). Decision trees. In: Maimon, O., Rokach, L. (eds) Data mining and knowledge discovery handbook, 165–192. Springer, Boston, MA. doi.org/10.1007/0-387-25465-X_9

[37] Sarmento, H., Peralta, M., Harper, L., Vaz, V., & Marques, A. (2018). Achievement goals and self-determination in adult football players–A cluster analysis. Kinesiology, 50(1), 43–51. doi.org/10.26582/k.50.1.1

[38] Soto, A., Camerino, O., Iglesias, X., Anguera, M.T., & Castañer, M. (2019). LINCE PLUS: Research software for behavior video analysis. Apunts Educación Fisica y Deportes, 3(137), 149–153. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2019/3).137.11

[39] Tenga, A., & Sigmundstad, E. (2011). Characteristics of goal-scoring possessions in open play: Comparing the top, in-between and bottom teams from professional soccer league. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 11(3), 545–552. doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2011.11868572

[40] Tenga, A., Holme, I., Ronglan, L. T., & Bahr, R. (2010). Effect of playing tactics on goal scoring in Norwegian professional soccer. Journal of Sports Sciences, 28(3), 237–244. doi.org/10.1080/02640410903502774

[41] Toda, K., Teranishi, M., Kushiro, K., & Fujii, K. (2022). Evaluation of soccer team defense based on prediction models of ball recovery and being attacked: A pilot study. Plos one, 17(1), e0263051. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263051

[42] Vogelbein, M., Nopp, S., & Hökelmann, A. (2014). Defensive transition in soccer–are prompt possession regains a measure of success? A quantitative analysis of German Fußball-Bundesliga 2010/2011. Journal of Sports Sciences, 32(11), 1076–1083. doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2013.879671

[43] Wilson, R. S., Smith, N. M., Melo de Souza, N., & Moura, F. A. (2020). Dribbling speed predicts goal‐scoring success in a soccer training game. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 30(11), 2070–2077. doi.org/10.1111/sms.13782

[44] Wright, C., Atkins, S., Polman, R., Jones, B., & Sargeson, L. (2011). Factors associated with goals and goal scoring opportunities in professional soccer. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 11(3), 438–449. doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2011.11868563

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: January 24, 2025

Accepted: May 30, 2025

Published: October 1, 2025

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en