Active Methodologies and Gender Equality in Physical Education: A Systematic Review

*Corresponding author: José Manuel Armada-Crespo armadacrespojm@gmail.com

Cite this article

Caracuel-Cáliz, R. F., Armada-Crespo, J. M., & Abad-Robles, M. T. (2025). Active methodologies and gender equality in physical education: A systematic review. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 162, 31-42. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2025/4).162.04

Abstract

Various studies have discussed the existence of gender inequality in physical education (PE) classes, pointing to lower motivation and participation among female students. It is essential to reflect on teaching practice to achieve a more equitable education free from gender stereotypes. Our objective was to perform a systematic review analyzing the influence of pedagogical models on gender equality in PE sessions in elementary and high school education, as well as to describe and analyze these interventions. For this purpose, a systematic review was conducted, based on the PRISMA method, using the databases Web of Science, Scopus, SportDiscus, and Eric, analyzing the scientific literature between 2000 and 2024 relating pedagogical models in PE with gender equality. A total of 521 articles were found, of which 16 studies were included after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The findings indicated that active methodologies had a positive impact on the promotion of gender equality in physical education classes, with female students’ motivation, participation, and commitment on a par with that of their male peers. The main conclusion of the research found that models such as Cooperative Learning, Teaching Games for Understanding, and certain hybrid models promoted a more equitable scenario, enhancing female students’ satisfaction and involvement and positively modifying perception of them among their peers.

Introduction

Gender Equality in Physical Education

Physical education (PE) represents a positive setting for addressing social needs (Baena-Morales et al., 2023) and integrating both social and personal aspects (Fernández-Rio, 2015; Manzano et al., 2020a).

In that regard, innovative trends in PE transcend solely motor-related content and aim to consolidate interdisciplinary learning and more comprehensive education for students based on perspectives such as neuroscience (Pellicer et al., 2015), new technologies (García et al., 2020), or active methodologies (Blázquez, 2017; León-Díaz et al., 2023). Furthermore, some of those innovations are based on simultaneous use of multiple perspectives to obtain better results and enhance the specific benefits of method, as is the case with hybrid pedagogical models (Guijarro et al., 2020).

On the other hand, within the scope of its 2030 Agenda, the United Nations (UN) has defined 16 goals related to achieving a fairer and more sustainable world. Those include Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls” (UN, 2015).

Multiple studies have discussed the unequal participation, interest, and motivation among female students in PE due to traditional teaching methods that reinforce stereotypes or emphasize physical qualities associated with the male sex (Arenas et al., 2022; Fernández-García et al., 2007; Llanos-Muñoz et al., 2022). On that topic, Blández-Ángel et al. (2007) offer a particularly illustrative example regarding stereotypes in physical activity and sports. They demonstrated how instrumental traits and activities related to strength, risk, endurance, or a higher level of aggression continue to be associated with the male sex, while affective and expressive traits and activities involving rhythm, expression, or flexibility continue to be associated with the female sex. The study also concluded that female students encounter significant obstacles to access the world of physical activity—traditionally associated with the male sex—and that both male and female students who manage to overcome stereotypes and access activities classified as of “the opposite sex” are subject to sexist comments (Blández-Ángel et al., 2007).

In light of these issues, the Guía para una educación física no sexista [Guide to Non-Sexist Physical Education] (Vázquez & Álvarez, 1996) and works by Fernández-García et al. (2007), and Sánchez-Hernández et al. (2022) later on, had already identified the need to broach PE classes through a co-ed approach that eliminates the universal masculine archetype, corrects sexist stereotypes, and develops all qualities regardless of sex or gender (Fernández-García et al., 2007; Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2022; Vázquez & Álvarez, 1996). In that sense, certain aspects such as teacher training, language, and teachers’ own beliefs and expectations of their students can impact whether PE is practiced with gender equality in mind or whether it perpetuates sexist stereotypes (Vázquez & Álvarez, 1996). Thus, it seems that some progress, albeit slow, has been made in overcoming certain stereotypes and beliefs regarding PE and gender, and there are coexisting realities that negatively affect both men and women (Alvariñas-Villaverde & Pazos-González, 2018). Along those lines, PE teachers’ involvement is a deciding factor in reducing and eliminating gender stereotypes, as is the participation and engagement of female students in PE classes and the incorporation of physical activity into their everyday lives (Reyes et al., 2024).

To connect SDG 5 with PE, given the psychosocial possibilities (Baena-Morales et al., 2023; Fernández-Rio, 2015; Manzano et al., 2020a) and innovative approaches of the latter (Blázquez, 2017; León-Díaz et al., 2023; Pellicer et al., 2015), critical reflection is essential to achieving gender equality in education and eliminating stereotypes related to physical activity and sports (Arenas et al., 2022; Fernández-García et al., 2007; Martos-García et al., 2020; Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2022; Vázquez & Álvarez, 1996).

PE Teaching Methods and Models and Their Relation to Gender Equality

The methodologies used in PE classes, with their pedagogical complexity, play a crucial role in the teaching-learning process (Fernández-Rio et al., 2021). Active methods, models (Fernández-Rio et al., 2021), and/or methodologies that are student-centered and whose curricula are adapted to students’ needs, abilities, and interests promote competency-based learning that fosters student autonomy and agency (Paños, 2017; Pérez-Pueyo, 2015; Pérez-Pueyo, 2010).

Likewise, different methods can impact student involvement considering that teacher engagement varies according to whether traditional or more participatory methods are used, with the focus mainly placed on students in the latter method (Hortigüela & Hernando, 2017, Méndez-Giménez et al., 2012; Pérez-Pueyo et al., 2020).

Multiple studies have shown how certain models, such as the Teaching Games for Understanding (TGfU) Model, foster gender equality. González-Espinosa et al. (2019) found that using this model in elementary school improved the performance of female students, compared to direct instruction. Cañabate et al. (2023) also showed that cooperative methodologies encourage equality, as opposed to competitive methods that tend to produce gender inequality.

Along those lines, Llanos et al. (2022) and Aparicio et al. (2024) pointed to improved motivation and reduced gender inequality when using the Sport Education Model and hybrid methodologies in high school settings. These results agree with other studies that address the need to tackle gender stereotypes in sports and physical activity (Amado et al., 2017; Gutierrez & García-López, 2012; Manzano-Sánchez et al., 2020b; Oliveros & Fernández-Río, 2022).

Therefore, the objectives of this study were as follows: 1) perform a systematic review to analyze the impact of pedagogical models on gender equality in PE classes in elementary and high school, 2) describe and analyze those interventions.

Method

Via a systematic review, this research analyzed studies on the impact of gender perspective-based teaching methodologies in PE classes using PRISMA (Page et al., 2021) and other systematic review guidelines (Moher et al., 2015).

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: a) studies published between 2000 and July 2024; b) full text had to be available; c) systematic reviews and meta-analyses were excluded; d) written in English, Spanish, or Portuguese; e) experimental or quasi-experimental intervention; f) scientific studies focused on the effects of applying an active methodology or pedagogical model with a gender-based perspective; and g) conducted in elementary or high school students. We also checked the references of the selected articles to ensure our search was thorough.

Search Strategy

The systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2021). We agreed to use the following search phrase: (pedagogic models OR teaching models OR educational models OR pedagogical models OR active approaches OR active methods OR active methodologies) AND (physical education) AND (primary education OR elementary education OR secondary education OR high school OR middle school) AND (intervention OR experimental OR quasi-experimental OR randomized controlled trial OR RCT OR controlled trial) AND (gender OR sex). We searched for articles across four databases (Web of Science, Scopus, SportDiscus, and Eric) from 1 June to 10 July 2024. After searching, any duplicate articles were removed.

Study Selection and Data Processing

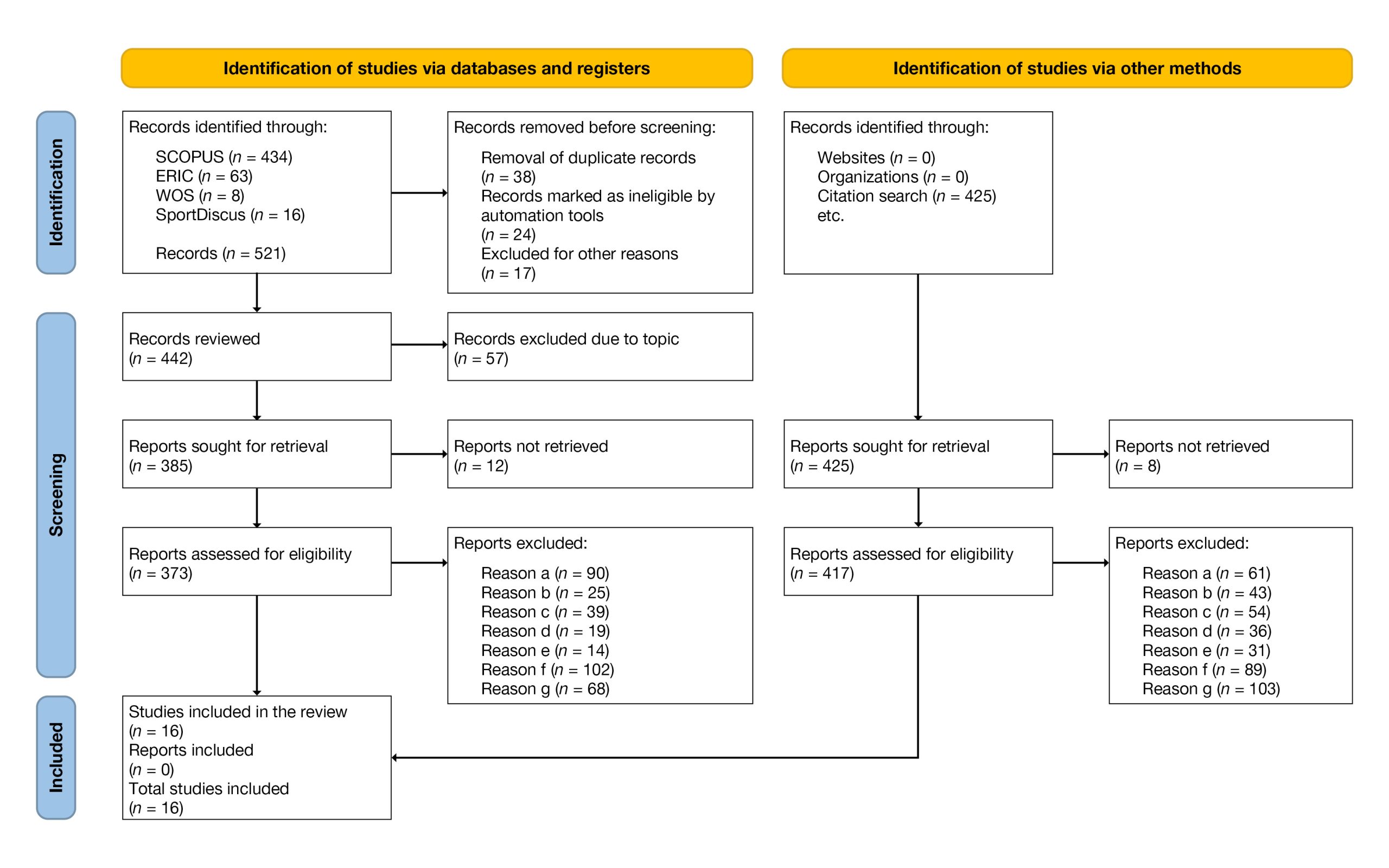

The articles were selected after reviewing their titles and abstracts. We obtained a total of 521 records. We ruled out 505 and selected 16 articles that met the inclusion criteria, focused on active methodologies and their relationship to gender equality in PE (see Figure 1). We also reviewed the references of said articles but identified no additional eligible studies. Two researchers reviewed the manuscripts independently and resolved any discrepancies by consensus. If no consensus could be reached, a third expert person was consulted.

Below is a flow chart that visually describes the process used to select the articles included in the review (Figure 1).

Quality Assessment

We evaluated the quality of the 16 selected articles using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria tool (Kmet et al., 2004). Two researchers rated each study for design, sample, methodology, analysis, and presentation, obtaining a final quality score.

The quality scores for the articles were expressed as percentages ranging between 0 and 100% and varied from .58 to .91. The raters’ agreement was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient, resulting in a score of .853 (p = < .001), indicating a “good” agreement level (Koo & Li, 2016). After implementing the raters’ agreement, a conservative cut-point was agreed on for article selection, resulting in the inclusion of studies with scores above 55%. The overall scores ranged between .58 and .85 (first reviewer) and between .61 and .91 (second reviewer).

Data Collection

The data from the selected articles were collected and verified in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2021). Two researchers with expertise in elementary and high school PE, psychosocial factors in education, and systematic reviews, evaluated the coding consistency, and achieved a 94% agreement level in the data extraction (González-Valero et al., 2019) by calculating the number of coincidences multiplied by 100 and divided by the total number of categories defined for each of the studies. This was then multiplied by 100 again.

Results

Study Characteristics

The study information was coded according to the following units of analysis: (1) Author(s), (2) Context, (3) Methodology/Study type, (4) Pedagogical model, (5) Variables, (6) Objective, and (7) Primary outcomes. The main characteristics of the analyzed studies are presented in Table 1.

These studies show that pedagogical models in PE influence both male and female students’ participation and motivation, and that of female students specifically. The Tactical Games and Cooperative Learning models help close the gender gap, as shown in the study by Gil-Arias et al. (2021).

Along the same line, Sánchez-Hernández et al. (2018) pointed out that Cooperative Learning promotes enhanced participation by female students and improves male students’ attitudes towards their female classmates, thus questioning gender relations. Cañabate et al. (2023) found that this approach promotes gender equality in PE.

Burgueño et al. (2019) reported that Sport Education improves female students’ motivation, while López-Lemus et al. (2023) stated that a hybrid model minimizes gender differences and promotes greater satisfaction and more physical activity.

The studies suggest that collaborative and tactical pedagogical models may positively influence inclusive learning and the handling of gender inequality in PE, thus fostering respect, cooperation, and student potential.

The analysis shows how pedagogical models like TGfU and Tactical Games may encourage behavior and motivation on a gender basis, thus minimizing inequality through cooperative approaches and promoting gender equality.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to perform a systematic review to analyze the impact of pedagogical models on gender equality in PE classes in elementary and high school and to describe and analyze those interventions. In elementary school, it has been shown that models like Cooperative Learning and TGfU contribute to minimizing gender stereotypes and promoting equal participation, motivation, and performance between male and female students (Cañabate et al., 2021; Gil-Arias et al., 2021; Gutierrez & García-López, 2012). These methodologies help foster an inclusive environment and promote equal participation and motivation between the genders (Baena-Morales et al., 2023; Hortigüela & Hernando, 2017, León-Díaz et al., 2023; Méndez-Giménez et al., 2012; Paños, 2017; Pérez-Pueyo et al., 2020).

Though awareness of gender stereotypes in high school is increasing, inequalities persist in certain physical activities, as seen in higher engagement by male students compared to female students (Gutierrez & García-López, 2012; Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2018). Nevertheless, some studies reported improved motivation and involvement among female students after implementing models such as the Sport Education Model or hybrid models (Aparicio et al., 2024; Guijarro et al., 2020; Lamoneda et al., 2023; López-Lemus et al., 2023; Pérez-Pueyo et al., 2020), which relates to the importance of teachers’ awareness of female students’ participation in PE (Reyes et al., 2024).

On the other hand, we observed that gender stereotypes were upheld in some cases, with higher participation by male students than by female students (Gutierrez & García-López, 2012; Manzano-Sánchez et al., 2020b; Oliveros & Fernández-Río, 2022), or vice versa (Amado et al., 2017), depending on the specific physical activity. In that regard, we found a larger number of studies indicating both the upholding of stereotypes and a lack of impact from the model applied, which promoted male students’ participation by 3 to 1 compared to models that promoted female students’ motivation or interest. This may be related to what Blández-Ángel et al. (2007) found regarding the two large sets of traits presented and the perception of PE, which portrays the masculine archetype as universal (Arenas et al., 2022; Fernández-García et al., 2007; Vázquez & Álvarez, 1996).

Pedagogical models such as Cooperative Learning, Sport Education, and TGfU and their hybrids were identified as having a positive impact on gender equality in PE (González-Espinosa et al., 2019; Gil-Arias et al., 2021). These approaches helped foster a more inclusive and equal environment, encouraging participation and performance in both male and female students, which is in line with the current literature (Guijarro et al., 2020; Hortigüela & Hernando, 2017, León-Díaz et al., 2023; Méndez-Giménez et al., 2012; Pérez-Pueyo et al., 2020).

Based on the information presented above, we observed seemingly promising results regarding the impact of pedagogical models in PE to help achieve the SDG 5 “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls” and, therefore, help promote a fairer and more sustainable educational environment (UN, 2015). Nevertheless, we did identify some limitations in terms of the overall impact of the pedagogical models on moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in female students, who presented lower levels of engagement in physical activity, even when a hybrid model was used (Oliveros & Fernández-Rio, 2022).

Despite these promising findings, we observed certain limitations such as the lack of detail about the tasks performed and variability in the instruments and ages in the reviewed studies. The need for more in-depth research into specific variables was also apparent. Furthermore, it must be said that the idea to study pedagogical models in PE in relation to gender equality demonstrates the possibilities of these models but does not guarantee any improvement in this regard. The development of prosocial behavior in educational physical activity scenarios is thought to be shaped more by the adults responsible for the class than by the method used (Pelegrín et al., 2010). Fundamental variables in this sense include preparation, attitude, language, or hidden curriculum, as well as other aspects communicated by the teacher (Alvariñas-Villaverde & Pazos-González, 2018; Reyes et al., 2024; Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2022; Vázquez & Álvarez, 1996). Future lines of research could focus on the study of a single pedagogical model, or a single variable related to gender equality in PE. Likewise, it could be interesting to address reflection and critical thinking in PE, within the actual pedagogical models, as a transformative practice for gender equality.

Conclusions

After analyzing the reviewed studies, we can conclude that pedagogical models in PE influence performance and motivation in both male and female students and can also be useful for minimizing gender inequality. Models like Cooperative Learning, TGfU, and hybrid models (which pair these approaches with the Sport Education Model) promote an inclusive and equal environment, allowing male and female students to actively participate and improve their performance. In situations where female students present low participation, both the activities and environment must be adapted to promote gender equality.

Cooperative and tactical models increase female students’ motivation and satisfaction, but also shift male students’ perceptions of them, helping female students feel more valued and empowered in what is a traditionally male-dominated space. These approaches minimize the gender differences observed in competitive settings. The Sport Education Model and the TGfU Model contribute to reducing demotivation and foster the intent to stay physically active in the long term. Likewise, we must mention that pedagogical models in PE do not guarantee that gender equality will be achieved, as they must be implemented correctly and with a critical eye. In that regard, methodology is one of the keys to increasing gender equality in PE but it does not guarantee it alone. Nor should it be considered the only relevant factor when aiming to achieve greater gender equality in PE environments.

The main practical application of the study involves implementing models based on cooperation and tactical games, as these offer a clear opportunity to improve students’ learning experiences and to foster an environment in which both male and female students can participate equally. This will help contribute to the students’ overall development in terms of physical, cognitive, social, and emotional abilities.

Therefore, ongoing teacher training and adapting curricula according to these methodologies are essential to guaranteeing inclusive and effective PE experiences that meet the needs of all students, regardless of gender.

References

[1] Alvariñas-Villaverde, M. & Pazos-González, M. (2018). Estereotipos de género en Educación Física, una revisión centrada en el alumnado. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 20(4), 154–163. doi.org/10.24320/redie.2018.20.4.1840

[2] Amado, D., Sánchez-Miguel, P. A., & Molero, P. (2017). Creativity associated with the application of a motivational intervention programme for the teaching of dance at school and its effect on the both genders. PLOS ONE, 12(3), e0174393. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174393

[3] Aparicio, R., Sánchez, A., Cenizo, J. M., & Vázquez, F. J. (2024). El BigBall-X a través de una hibridación de modelos para contribuir al ODS 5 y ODS 17 en la Educación Física (The BigBall-X through a hybridization of models to contribute to SDG 5 and SDG 17 in Physical Education). Retos. Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 56, 216–227. doi.org/10.47197/retos.v56.102504

[4] Arenas, D., Conti, J. V., & Mas, A. M. (2022). Estereotipos de género y tratamiento diferenciado entre chicos y chicas en la asignatura de educación física: una revisión narrativa. Retos: nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación, 43, 342–351. doi.org/10.47197/retos.v43i0.88685

[5] Baena-Morales, S., Barrachina-Peris, J., García-Martínez, S., González-Víllora, S., & Ferriz-Valero, A. (2023). La Educación Física para el Desarrollo Sostenible: un enfoque práctico para integrar la sostenibilidad desde la Educación Física. Revista Española de Educación Física y Deportes, 437(1), 1–15. doi.org/10.55166/reefd.vi437(1).1087

[6] Blández-Ángel, J. Fernández-García, E., & Sierra-Zamorano, M. Á. (2007). Estereotipos de género, actividad física y escuela: La perspectiva del alumnado. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación de Profesorado, 11(2).

[7] Blázquez, D. (2017) (Ed.). Métodos de enseñanza en Educación Física. Enfoques innovadores para la enseñanza de competencias. Inde

[8] Burgueño, R., Cueto-Martín, B., Morales-Ortiz, E., & Medina-Casaubón, J. (2020). Influencia de la educación deportiva sobre la respuesta motivacional del alumnado de bachillerato: Una perspectiva de género (Influence of sport education on high school students’ motivational response: A gender perspective). Retos. Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 37, 546–555. doi.org/10.47197/retos.v37i37.70880

[9] Cañabate, D., Bubnys, R., Nogué, L., Martínez-Mínguez, L., Nieva, C., & Colomer, J. (2021). Cooperative Learning to Reduce Inequalities: Instructional Approaches and Dimensions. Sustainability, 13(18), 10234. doi.org/10.3390/su131810234

[10] Cañabate, D., Gras, M. E., Pinsach, L., Cachón, J., & Colomer, J. (2023). Promoting cooperative and competitive physical education methodologies for improving the launch’s ability and reducing gender differences. Journal of Sport and Health Research, 15(3). doi.org/10.58727/jshr.94911

[11] Cochon, O., Margas, N., Cece, V., & Lentillon-Kaestner, V. (2024). The effects of the Jigsaw method on students’ physical activity in physical education: The role of student sex and habituation. European Physical Education Review, 30(1), 85–104. doi.org/10.1177/1356336X231184347

[12] Fernández-García, E., Blández-Ángel, J., Camacho-Miñano, M.J., Zamorano-Sierra, M. A., Vázquez-Gómez, B., Rodríguez-Galiano, I., Mendizabal-Albizu, S., Sánchez-Bañuelos, F., & Sánchez-Sánchez, M. (2007). Estudios e investigaciones. Estudio de los estereotipos de género vinculados con la actividad física y el deporte en los centros docentes de educación primaria y secundaria: Evolución y vigencia, diseño de un programa integral de acción educativa. (Vol. 168). Ministerio de Igualdad.

[13] Fernández-Río, J. (2015). El Modelo de Responsabilidad Personal y Social y el Aprendizaje Cooperativo. Conectando Modelos Pedagógicos en la teoría y en la práctica de la Educación Física. In Actas del IV Congreso Internacional de Educación Física. Querétaro, México.

[14] Fernández-Rio, J., Hortigüela-Alcalá, D. y Perez-Pueyo, A. (2021). En Pérez Pueyo, Á. L., Hortigüela-Alcalá, D., Fernández Río, J., Calderón, A., García López, L. M., González-Víllora, S., Manzano-Sánchez, D., Valero-Valenzuela, A., Hernando-Garijo, A., Barba-Martín, R.A., Méndez-Giménez, A., Baena-Extremera, A., Julián, J.A., Peiró-Velert, C., Zaragoza-Casterad, J., Aibar-Solana, A., Chiva-Bartoll, O., Flores-Aguilar, G., Gutiérrez-García, C., López-Pastor, V.M., Heras-Bernardino, C., Casado-Berrocal, O.M., Herrán-Álvarez, I. & Sobejano Carrocera, M. (2021). Modelos pedagógicos en educación física: qué, cómo, por qué y para qué. León: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de León (pp. 11–25).

[15] García, J., Navarro, D. & Merino, J. (2020) . Uso de nuevas tecnologías en Educación Física. En B. Sánchez-Alcaraz, A. Valero, D. Navarro y J. Merino (Coord.), Metodologías emergentes en Educación Física (pp. 83–112). Wanceulen.

[16] Gil-Arias, A., Harvey, S., García-Herreros, F., González-Víllora, S., Práxedes, A., & Moreno, A. (2021). Effect of a hybrid teaching games for understanding/sport education unit on elementary students’ self-determined motivation in physical education. European Physical Education Review, 27(2), 366–383. doi.org/10.1177/1356336X20950174

[17] González-Valero, G., Ubago Jiménez, J. L., Castro Sánchez, M., García Martínez, I., & Sánchez Zafra, M. (2019). Prevención y tratamiento de lesiones lumbares con herramientas físico-médicas. Una revisión sistemática. Sportis. Scientific Journal of School Sport, Physical Education and Psychomotricity, 5(2), 232–249. doi.org/10.17979/sportis.2019.5.2.3409

[18] González-Espinosa, S., Mancha-Triguero, D., García-Santos, D., Feu, S., & Ibáñez, S. (2019). Difference in Learning Basketball according to Gender and Teaching Methodology. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 28(3), 86–92.

[19] Guijarro, E., Evangelio, C., González Víllora, S., y Arias-Palencia, N. M. (2020). Hybridizing Teaching Games for Understanding and Cooperative Learning: an educational innovation. Education, Sport, Health and Physical Activity, 4(1), 49–62.

[20] Gutierrez, D., & García-López, L. M. (2012). Gender differences in game behaviour in invasion games. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 17(3), 289–301. doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2012.690379

[21] Hortigüela-Alcalá, D., & Hernando-Garijo, A. (2017). Teaching Games for Understanding: A Comprehensive Approach to Promote Student’s Motivation in Physical Education. Journal of Human Kinetics, 59, 17–27. doi.org/10.1515/hukin-2017-0144

[22] Kmet, L. M., Lee, R. C., & Cook, L. S. (2004). Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research.

[23] Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

[24] Lamoneda J., Rodríguez, B., Palacio, E. S., & Matos, M. (2023). Percepciones de los estudiantes sobre la educación física en el programa It Grows: actividad física, deporte e igualdad de género (Student perceptions of physical education in the It Grows program: physical activity, sport and gender equality). Retos. Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 48, 598–609. doi.org/10.47197/retos.v48.96741

[25] Llanos-Muñoz, R., Leo, F. M., López-Gajardo, M. Á., Cano-Cañada, E., & Sánchez-Oliva, D. (2022). ¿Puede el Modelo de Educación Deportiva favorecer la igualdad de género, los procesos motivacionales y la implicación del alumnado en Educación Física? Retos. Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 46, 8–17. doi.org/10.47197/retos.v46.92812

[26] León-Díaz, O, Martínez Muñoz, L. F. ., & Santos Pastor, M. L. (2023). Metodologías activas en la Educación Física. Una mirada desde la realidad práctica (Active methodologies in Physical Education. A look from practical reality). Retos, 48, 647–656. doi.org/10.47197/retos.v48.96661

[27] López-Lemus, I., Del-Villar Álvarez, F., Gil-Arias, A., & Moreno-Domínguez, A. (2023). Equidad de Género y motivación en Educación Física ¿Podría ayudarnos la hibridación de modelos pedagógicos? Movimento, 29, 1–25. doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.128080

[28] Manzano-Sánchez, D., Merino Barrero, J. A., & Sánchez-Alcaraz Martínez, B. J. (2020a). El modelo de responsabilidad personal y social. En B. Sánchez-Alcaraz, A. Valero, D. Navarro y J. Merino (Coord.), Metodologías emergentes en Educación Física (pp. 113–125). Wanceulen.

[29] Manzano-Sánchez, D., Gómez-Mármol, A., & Valero-Valenzuela, A. (2020b). Student and Teacher Perceptions of Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility Implementation, Academic Performance and Gender Differences in Secondary Education. Sustainability, 12(11), 4590. doi.org/10.3390/su12114590

[30] Martos-García, D., Fernández-Lasa, U., & Usabiaga, O. (2020). Coeducation and team sports. Girls’ participation in question. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 15(45). doi.org/10.12800/ccd.v15i45.1518

[31] Méndez-Giménez, A., Fernández-Río, J., y Casey, A. (2012). Using the TGFU tactical hierarchy to enhance student understanding of game play. Expanding the Target Games category. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 7(20), 135–141. doi.org/10.12800/ccd.v7i20.59

[32] Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L. A. & PRISMA-P Group (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1. doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

[33] Oliveros, M., & Fernandez-Rio, J. (2022). Pedagogical models: Can they make a difference to girls’ in-class physical activity? Health Education Journal, 81(8), 913–925. doi.org/10.1177/00178969221128641

[34] ONU. (2015). La Agenda para el Desarrollo Sostenible.

[35] Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., & Moher, D. (2021). Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 103–112. doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003

[36] Paños, J. (2017). Educación emprendedora y metodologías activas para su fomento. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación Del Profesorado, 20(3), 33. doi.org/10.6018/reifop.20.3.272221

[37] Pelegrín, A., Garcés, E., & Cantón, E. (2010). Estudio de conductas prosociales y antisociales. Comparación entre niños y adolescentes que practican y no practican deporte. Informació psicològica, (99), 64–78.

[38] Pellicer, I., López, L., Mateu, M., Mestres, L., & Monguillot, M. (2015). NeuroEF La Revolución de la Educación Física desde la Neurociencia. Inde.

[39] Pérez-Pueyo, Á. (2016). El Estilo Actitudinal en Educación Física: Evolución en los últimos 20 años (The attitudinal style in Physical Education: Evolution in the past 20 years). Retos. Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 29, 207–215. doi.org/10.47197/retos.v0i29.38720

[40] Pérez-Pueyo, Á. (2010). El estilo actitudinal. Una propuesta metodológica basada en las actitudes. ALPE.

[41] Pérez-Pueyo, A., Hortigüela-Alcalá, D. y Fernandez-Río, J. (2020). Evaluación formativa y modelos pedagógicos: Estilo actitudinal, aprendizaje cooperativo, modelo comprensivo y educación deportiva. Revista Española de Educación Física y Deportes, 428, 47-66. doi.org/10.55166/reefd.vi428.881

[42] Reyes, L., Oliver, K.L., García López, L.M., & Camacho-Miñano, M. J. (2024). El Enfoque Activista para la enseñanza de la Educación Física y el Deporte: situando a las niñas y chicas adolescentes en el centro. In Construyendo la Justicia Social a través de la Educación Física y el Deporte: Un enfoque salutogénico y crítico (pp. 135–143). Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha.

[43] Sánchez-Hernández, N., Martos-García, D., Soler, S., & Flintoff, A. (2018). Challenging gender relations in PE through cooperative learning and critical reflection. Sport, Education and Society, 23(8), 812–823. doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2018.1487836

[44] Sánchez-Hernández, N., Soler-Prat, S. & Martos-García, D. (2022). La Educación Física desde dentro. El discurso del rendimiento, el currículum oculto y las discriminaciones de género, Ágora para la Educación Física y el Deporte, 24, 46–71 doi.org/10.24197/aefd.24.2022.46-71

[45] Smith, L., Harvey, S., Savory, L., Fairclough, S., Kozub, S., & Kerr, C. (2015). Physical activity levels and motivational responses of boys and girls. European Physical Education Review, 21(1), 93–113. doi.org/10.1177/1356336X14555293

[46] Vázquez, B. y Álvarez, G. (1996) (Coord). Guía para una Educación Física no Sexista. Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia. Dirección General de Renovación Pedagógica.

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: January 13, 2025

Accepted: June 16, 2025

Published: October 1, 2025

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en