A multivariate analysis of physical fitness and competitive performance in young handball players

*Corresponding author: Roger Font rfont@tecnocampus.cat

Cite this article

Font, R., Karcher, C., Tremps, V. & Irurtia, A. (2025). A multivariate analysis of physical fitness and competitive performance in young handball players. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 160, 18-25. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2025/2).160.03

Abstract

Handball as a team sport requires certain attributes of physical fitness. Higher upper and lower body power values must be developed throughout the entire player training process. The aim of the present study was to characterise the jumping and throw kinetics of nine young talented handball players during three sport seasons (Season 1: 14.1 ± 0.9 age; 70.6 ± 5.9 kg; 171.6 ± 10 cm; Season 2: 15.1 ± 0.9 age; 74.7 ± 6.5 kg; 177.7 ± 8.2 cm; Season 3: 16.1 ± 0.9 age; 78.3 ± 6.7 kg; 179.9 ± 6.7 cm) and assess possible relationships with competitive performance. The physical fitness tests performed were the squat jump (SJ), the counter movement jump (CMJ), the Abalakov test (ABK) and the 3-kg medicine ball throw, analysing jump heights and throwing distance. We designed a 3-season follow-up study with two checkpoints for each season. The athletic performance of each player was established individually by determining a competitive ranking that was contrasted from a bivariate and multivariate perspectives, with somatic characteristics and the physical fitness tests performed. All physical fitness tests improved throughout the three seasons, although differently between the preseason and postseason. The 3-kg medicine ball throw test was moderately correlated with sports performance and, together with the Abalakov test, explained it with a low predictive power. We concluded that, despite the improvement in the jumping and throwing ability over three seasons, this does not seem to have a sufficiently consistent relationship with the competitive level of this group of young talented handball players. Further research is needed to control for parameters of biological age and cognitive complexity.

Introduction

Handball is an intermittent and complex situational sport regulated by the International Handball Federation (IHF, 2017). According to the playing position, handball players have a specific anthropometric (Karcher & Buchheit, 2014; Martínez-Rodríguez et al., 2020) and physical fitness profile (Aguilar-Martínez et al., 2012; Font et al., 2023; Karcher & Buchheit, 2014; Schwesig et al., 2017).

Although research on the anthropometric and physical fitness profile has been widely studied in professional handball players (Karcher & Buchheit, 2014), it has not been so widely studied in young talents during their formative stage and how this relates to their competitive performance (Lidor et al., 2005; Matthys et al., 2011; Matthys et al., 2013a; Matthys et al., 2013b; Zapartidis et al., 2009).

From an early age to the elite, modern and current handball requires high values of strength, power and speed to perform technical and tactical skills at maximum intensity during training and matches (Buchheit et al., 2009; Gorostiaga et al., 1999; Karcher & Buchheit, 2014; Matthys et al., 2011; Zapartidis et al., 2009). For example, the importance of the sprints over short distances is well characterised, and these are low in percentage terms vs. the total volume of meters travelled during a match (Font et al., 2021b), yet paradoxically decisive and defining when resolving situations with utmost efficiency (Ghobadi et al., 2013) and with a high risk of injury (Mónaco et al., 2019).

The process of handball training in formative stages, and hence in relation to identifying sports talent, necessarily involves aspects including monitoring and developing maximal strength, power and speed values in both lower and upper limbs (Lidor et al., 2005; Mohamed et al., 2009). Accordingly, the categorisation of strength training in this sport is usually recognised as it relates to shots, jumps, or hand-to-hand contact with an opponent (Karcher & Buchheit, 2014).

Most of the physical fitness tests used in handball are generic. Generic tests have been carried out to obtain the speed profile of the players (Krüger et al., 2014), the metabolic profile of the players (Schwesig et al., 2017), the heart rate needs of young players in competition (Ortega-Becerra et al., 2020), the strength values in classic exercises such as the bench press or the squad (Ingebrigtsen et al., 2013) or the power in jumps such as the countermovement jump (Massuça et al., 2015; Matthys et al., 2013a). These conditional tests are important as fitness has been shown to influence the way players approach training and their performance (Manzi et al., 2010). Their main drawback is that the inherent specificity of the technical movement is lost, which unquestionably has a direct impact on the greater or lesser effectiveness of a specific technical-tactical action that is the final goal, pursued by any coach (Schwesig et al., 2017; Wagner et al., 2016).

There is also research that has focused on knowing the metabolic profile in specific tests made up of handball movements on the court in order to improve the conditional profile of the players and at the same time to evaluate them (Michalsik & Wagner, 2021; Wagner et al., 2016).

By contrast, the benefits of this type of fundamental/generic test are (Font, et al., 2021a; Irurtia et al., 2010): 1) they make it possible to locate the conditional component (strength, power, speed) by isolating or minimising the influence of the specific technical component, thus being able to clearly separate the evolution of one or the other parameter; 2) they allow a distribution that is simple and therefore applicable in both young and professional players; 3) this latter characteristic enables these tests to be used in the application of a longitudinal comparison that establishes an individual’s level of conditional evolution over time; and 4) they allow comparison between different sports.

The identification of sports talent in handball is therefore a burgeoning area of current scientific and professional interest (Matthys et al., 2011). As far as we know, there are not many studies which, with a longitudinal design and using basic physical fitness tests have examined the evolution of the conditional characteristics of young talented handball players, trying to relate and/or explain these with their sports performance. The purpose of this study was to analyse the physical fitness kinetics of a group of young talented handball players throughout three sports seasons with two checkpoints (preseason and postseason). Basic jumps corresponding to Bosco’s battery and 3-kg ball throw were applied in order to analyse the physical fitness characteristics of the lower and upper limbs, respectively. Finally, the possible relationship and/or explanation of the competitive performance of each player was analysed according to the level of performance in those tests.

Methodology

Study Design

This is a follow-up study that applies correlation (bivariate) and multiple regression analysis (multivariate) by setting a series of independent variables (physical fitness tests) and a dependent variable (sports performance). The independent variables (n = 6) were: body mass (kg), height (cm), throwing a 3-kg Medicine Ball (MB, m), Squat Jump (SJ, cm) Counter Movement Jump (CMJ, cm), and CMJ Abalakov (ABK, cm). The dependent variable was sports performance based on the score obtained by each player arising from their participation and sports achievements throughout the timeframe analysed in their club by expert coaches at national team levels (Table 1).

Participants

Nine male players in formative teams of a top European handball club (Season 1: 70.6 ± 5.9 kg; 171.6 ± 10 cm; Season 2: 74.7 ± 6,5 kg; 177.7 ± 8.2 cm; Season 3: 78.3 ± 6.7 kg; 179.9 ± 6.7 cm) were used to examine the evolution of the physical fitness tests conducted in the 2013–2014 (Season 1), 2014–2015 (Season 2) and 2015–2016 (Season 3). The inclusion criteria were: a) belonging to the youth academy of the same handball club; and b) having actively competed during the season analysed. On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were: a) having been injured or being convalescent at the time and for up to two weeks before being analysed; and b) not having done any of the tests in the three seasons. Table 2 shows the chronological age ranges of the players in relation to the competitive categories in which each of them competed during the three seasons examined.

Table 2

Number of handball players analysed per sport season and ranges of chronological age.

Throughout the study, the moral and ethical commitment to confidentiality in the handling of personal data was respected. The club, as the owner of the rights of the players, allowed the technician, in this case the author of this research paper, to use this information to promote the scientific progress of this sport. In addition, these tests were used throughout different seasons to assess the assimilation of conditional work by the players of the formative teams. Finally, each player signed the corresponding informed consent document accepting their participation in the study and their right to abandon it at any time.

This study complied with the rules and recommendations proposed at the Helsinki Conference for research in humans (Harriss & Atkinson, 2015). The data came from daily monitoring of all the players in the team throughout every sport season. Consequently, the approval of an ethics committeewas not required. (Winter & Maughan, 2009).

Material and Instruments

All the tests (body mass, height, MB, SJ, CMJ, ABK) were performed on the same day with a random chronological order between MB and the jump tests. Each season was recorded during the preseason (at the beginning of the preparation, with a minimum of 4 weeks before the first official competition) and (2) postseason (right after the last official competition). All the tests were performed for the whole sample and always in the same handball training sports hall by a single researcher, the author of this study.

Body mass and height were measured by a Seca 220® telescopic stadiometer (measuring range: 85-200 cm, precision: 1 mm) and a previously calibrated Seca 710® scale (capacity: 200 kg, precision: 50 g). Physical fitness tests were performed prior to the activation phase as a guided warm-up. In the case of the jumps, these tests are widely used in handball and their high reliability is also reported in young players (Font, et al., 2021a; Oliveira et al., 2014); only the best of three attempts made by each athlete was recorded. The jump tests used were tailored to the protocols described in the international literature (Font, et al., 2021a; Ingebrigtsen et al., 2013; Massuça et al., 2015). Their choice is justified by the considerations put forward by Gorostiaga et al. (2005) in relation to the characteristics of jumping in handball: a) squat jump (SJ); b) counter movement jump (CMJ); c) Abalakov (ABK). They were carried out using the Chronojump® contact platform and jump monitoring equipment (Chronojump Boscosystem, Barcelona, Spain). The hardware was connected to a computer which displayed the vertical jump height (cm) using free software (2.0.2., Chronojump Boscosystem Software, Barcelona, Spain) (Cadens et al., 2023; Font, et al., 2021a). The previously established recommendations for young handball players (Fernández-Romero et al., 2017) were followed for throwing the 3 kg medicine ball with three throws and recording only the best one.

Statistical Analysis

Basic descriptive statistics (average and standard deviation) were used to express evolution over three seasons together with the evolution of each of the physical fitness tests applied at the rate of two control points per season. The Shapiro-Wilks test confirmed the non-normality of the distribution. Therefore, non-parametric statistics were applied: a) the Wilcoxon test was used to check for possible differences between each macrocycle; and b) the highest value of each player was chosen for each season and the Friedman test was used to analyse differences between seasons. If significant differences were found, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used again. The degree of correlation between each of the tests analysed and between them and sports performance was examined using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Finally, multiple regression analyses were carried out to assess how far the independent variables explained the dependent variable (sports performance). The level of significance was p < .05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 23.0 (SPSS Statistics, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

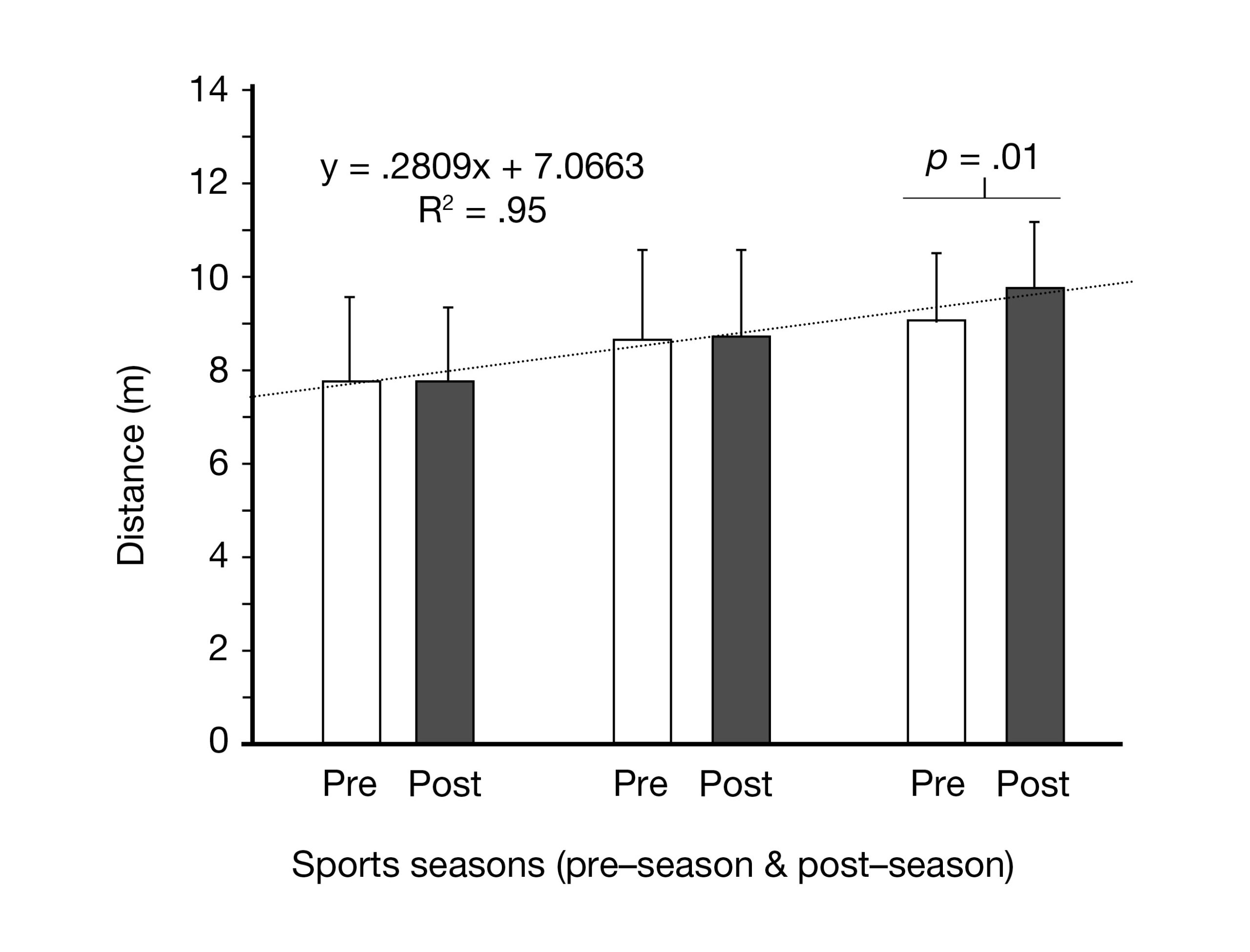

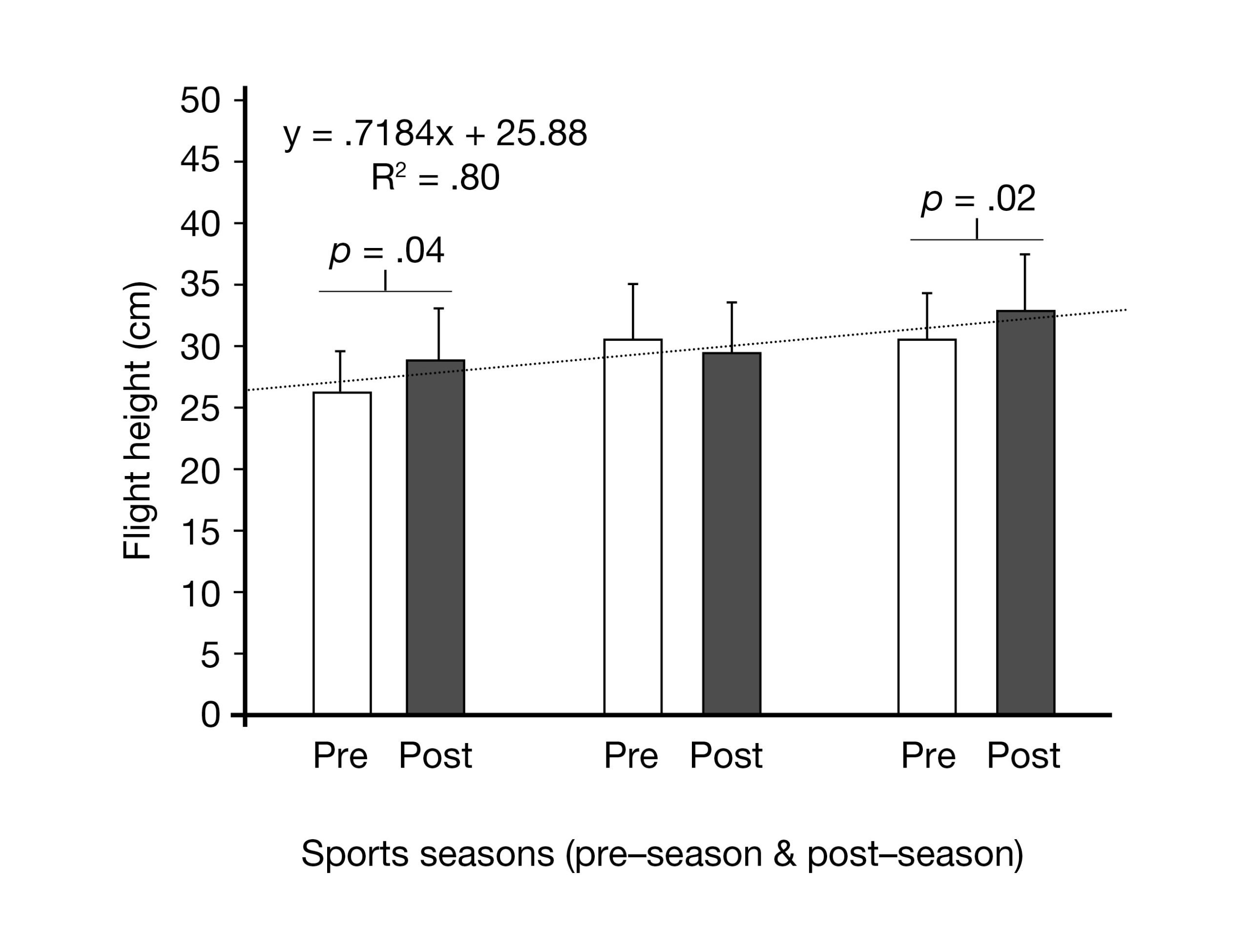

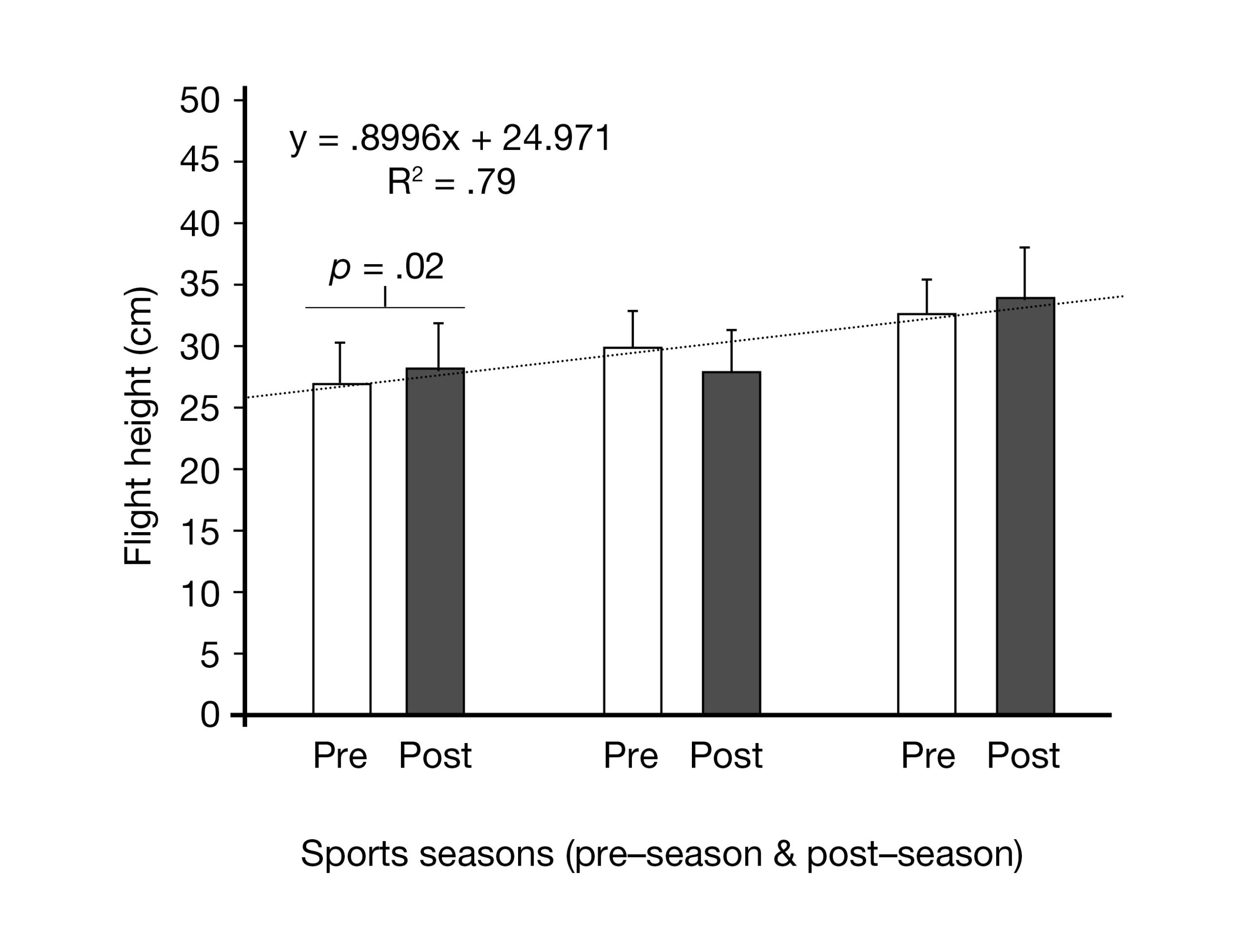

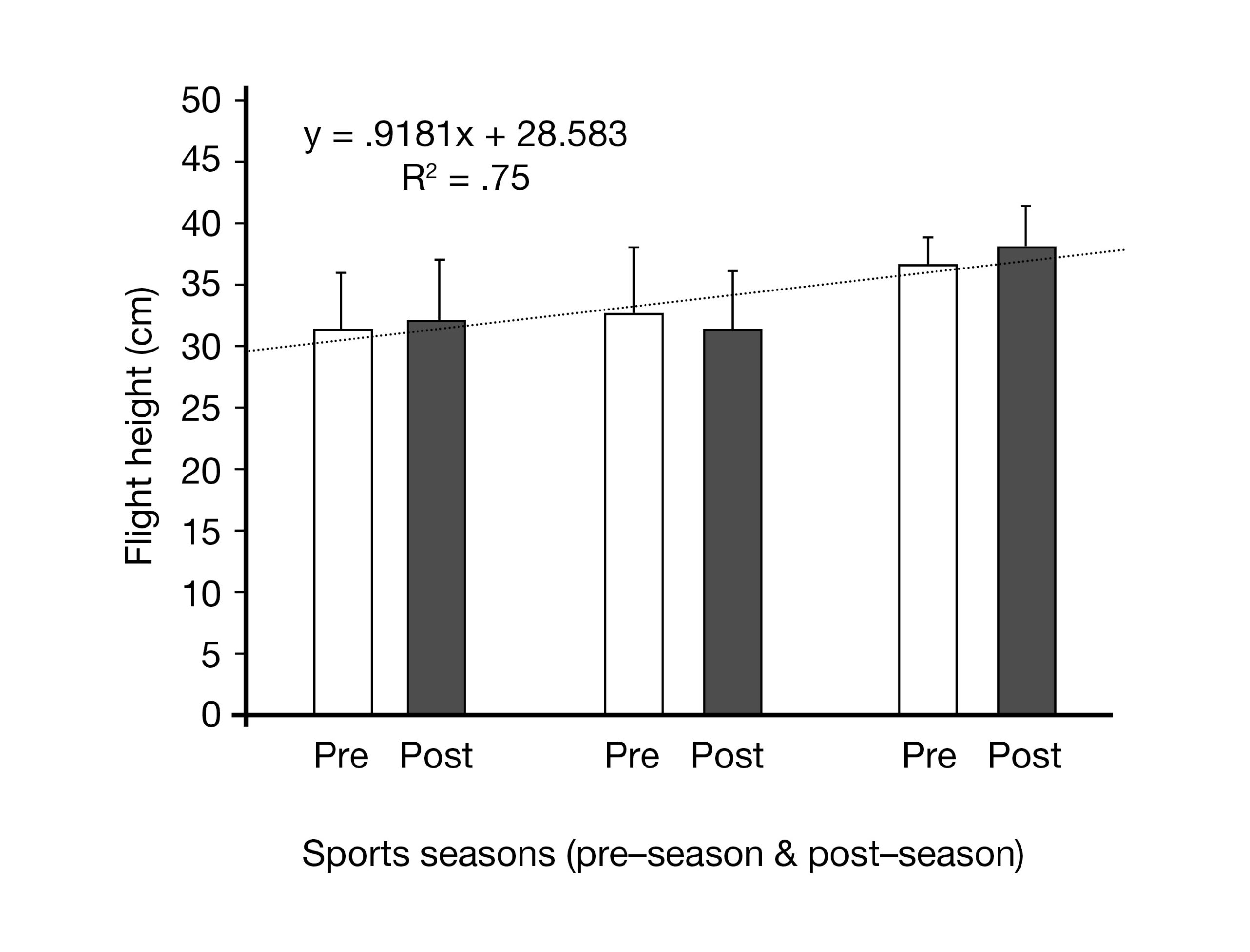

Figures 1 ,2, 3 and 4 show the evolution of the physical fitness tests (MB, SJ, CMJ, ABK) over the three seasons examined, respectively. Additionally, the significant differences between the two macrocycles analysed for each season are shown.

Table 3 shows the comparison between seasons of all the variables analysed, in this case based on the best values recorded in each test.

Body mass correlates significantly with performance (r = .39, p = .04). By contrast, the only physical fitness test that registers a significant correlation, albeit slight, with sports performance is the 3-kg medicine ball throw test: r = .43; p = .02. The multiple regression analysis selects two variables as explanatory factors of performance to generate the following equation: – 28.773 + (4.613 · 3 kg ball throw) + (1.348 · ABK) with very low predictive power of R2adjusted = .16; p = .04.

Discussion

Few longitudinal studies have examined the evolution of the components of physical fitness in young handball players up to the earliest ages of elite sport. Although the increase in all parameters over time is confirmed, the relationship between each of them and with athletic performance is very low. Furthermore, when a multivariate analysis is applied by introducing all the variables, the statistical model is not able to explain sports performance with sufficient predictive power.

Only one longitudinal study (Matthys, et al., 2013b) and two cross-sectional studies are known to have analysed the anthropometric and physical fitness profile of young handball players (Matthys et al., 2012;Matthys, et al., 2013a). In the first, 94 players aged 13 to 16 years were classified as elite and non-elite competitive level. They were monitored for three years without observing significant differences in any of the physical fitness tests monitored, except for the CMJ, with better performance in elite players compared to non-elite players. Regarding the cross-sectional studies, based on biological age criteria and stratifying the 472 players by playing positions, authors confirmed the linear evolution of some physical fitness tests including the ABK. However, in addition to the design itself, the main limitation of these studies (which also affects ours) is the absence of any monitoring of training load. Consequently, apart from evaluating the increase or not of the analysed variables, to date the exact reasons why these improvements occur and their relationship, greater or lesser, with competitive performance are unknown.

In this context, it has now been shown that the kinetics of the physical fitness of young handball players over time is linear in the ages prior to peak height velocity (PHV) and exponential during the PHV (Matthys, et al., 2013a). Unfortunately, the present study, despite the high athletic level of the study sample, could not apply biological age indicators. However, although it is essential to have a biological age parameter in any training process during childhood and adolescence that determines the maturity status of each young athlete in order to be able to interpret the results, there are precedents in handball where no significant differences were noted among players of more or less advanced maturity status in a series of physical fitness tests (Lidor et al., 2005). Thus, the greatest increases in physical fitness occur in the older age groups (15–16 years), most likely conditioned by a hormonally hyperactivated biological status (Malina et al., 2015; Matthys, et al., 2013b). Therefore, although all players increase their physical strength and power, it is those in the highest competitive sport category who register the greatest values and increases (Matthys et al., 2012; 2013a; 2013b).

On the other hand, when the focus is placed on the different tests used, assessment of the evolution of conditional behaviour between upper limbs, in this case throwing the medicine ball (MB), and lower limbs (SJ, CMJ, ABK) also confirms differences which endorse the importance of conducting strength-power work between limbs using a range of action strategies (Gorostiaga et al., 1999, 2005). In relation to the upper body, the MB test records the highest increases in this study with a solid linear evolution over the three seasons as shown by a coefficient of determination of 95%. This links with previous studies which, even obtaining similar results, nevertheless, emphasise the need to perform tests that assess handball skills, in this case directly related to the handball throwing technique (Lidor et al., 2005) or even adding a tactical opposition action to the shot (Rivilla-García et al., 2011). From this point of view, it is evident that to perform a jump throw (typical of the situational context of a handball match) it will be necessary to register optimal power values in the lower body and thus achieve the greatest number of offensive advantages when overcoming the defensive blocking (Gorostiaga et al., 1999, 2005).

In all cases, as different analysis components are added to the same test (direct magnitudes of speed, acceleration, distance, qualitative elements of technical execution, inclusion of tactical efficiency indicators, etc.), the complexity of its analysis increases, and with it the interpretation of its results (Zapartidis et al., 2009). This is the main reason why the MB is used as a physical fitness test to assess throwing function in youth club players. This test provides coaches and technical staff with an accessible way of assessment to obtain basic information about their players’ throwing capabilities, even though it is not the most specific way to do so (Aguilar-Martínez et al., 2012). In relation to the lower body, a good part of the previous studies has evaluated their players using a vertical jump. Mohamed et al. (2009) examined various 14 and 16-year-old elite and non-elite players and observed that the elite ones obtained better results than their non-elite counterparts. In turn, 16-year-old players performed better than 14-year-old ones. These results, which in point of fact seem quite logical, again match the ones recorded in this study where the largest increases take place in the last sports season and therefore at the players’ oldest age. However, this logic should be approached with some caution since other studies, this time cross-sectional, did not register differences in SJ or CMJ when comparing under-16 and under-18 elite players (Ingebrigtsen et al., 2013).

Finally, from a multivariate perspective, the contribution and/or relationship of each of the variables analysed with respect to the sports performance of each player is low. Firstly, the body mass and sports performance relationship seem to be explained by some previously documented logical reasons (Malina et al., 2015). Indeed, the increase in body mass of young athletes is directly influenced by the increase in their height and also in the peripubertal period by the increase in their muscle mass. When all the variables are analysed as a whole, only MB and ABK can be selected as indicators of the performance of the players, albeit with low predictive power. However, the technical component of both tests, which is higher than the other tests analysed, might suggest the influence on the results of a coordinative component, which is to some extent beyond the scope of the proposed objective as the intention was to analyse only physical conditional aspects using these tests.

Conclusions

Both anthropometric variables (body mass and height) and the physical fitness tests (MB, SJ, CMJ, ABK) show a tendency to increase linearly throughout the three seasons examined. Nevertheless, it is in the last sports season when the increases augment to a greater degree, probably due to the occurrence of PHV, even though this is not a factor controlled in this study. None of the variables analysed has a sufficiently high relationship with the sports performance of the players either individually or based on the contribution made by all of them as a whole. However, MB (upper body) and ABK (lower body) are selected by the multiple regression model. These tests are made up of a more demanding technical execution pattern, something which needs to be analysed in subsequent studies. More research is needed to address all the aspects discussed here in the construction of their design, mainly indicators of biological age, control of training load and a multidimensional perspective of performance. Sports performance is multifactorial. If the aim is to improve it, exclusively analysing anthropometric and/or conditional parameters seems not to be enough for team sports. In all cases complex longitudinal follow-up needs to be conducted and coaches will need the support of an expert methodologist in order to do this. The identification of sports talent increasingly calls for perfect synergy between experience and science.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the players who participated in this study, the coaching staff and medical services of FC Barcelona and the FC Barcelona Performance Department for giving us the opportunity to carry out this study.

References

[1] Aguilar-Martínez, D., Chirosa, L. J., Martín, I., Chirosa, I. J., & Cuadrado-Reyes J. (2012). Efecto del entrenamiento de la potencia sobre la velocidad de lanzamiento en balonmano (Effect of power training in throwing velocity in team handball). Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte, 12, 729–744.

[2] Buchheit, M., Laursen, P. B., Kuhnle, J., Ruch, D., Renaud, C., & Ahmaidi, S. (2009). Game-based training in young elite handball players. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 30(4), 251–258. doi.org/10.1055/s-0028-1105943

[3] Cadens, M., Planas-Anzano, A., Peirau-Terés, X., Benet-Vigo, A., & Fort-Vanmeerhaeghe, A. (2023). Neuromuscular and Biomechanical Jumping and Landing Deficits in Young Female Handball Players. Biology, 12(1), 134. doi.org/10.3390/biology12010134

[4] Fernández-Romero, J. J., Suárez, H. V., & Carral, J. M. C. (2017). Selection of talents in handball: anthropometric and performance analysis. Revista Brasileira de Medicina Do Esporte, 23(5), 361–365. doi.org/10.1590/1517-869220172305141727

[5] Font, R., Irurtia, A., Gutierrez, J. A., Salas, S., Vila, E., & Carmona, G. (2021a). The effects of COVID-19 lockdown on jumping performance and aerobic capacity in elite handball players. Biology of Sport, 38(4), 753–759. doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2021.109952

[6] Font, R., Karcher, C., Loscos-Fàbregas, E., Altarriba-Bartés, A., Peña, J., Vicens-Bordas, J., Mesas, J., & Irurtia, A. (2023). The effect of training schedule and playing positions on training loads and game demands in professional handball players. Biology of Sport, 40(3), 857-866. doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2023.121323

[7] Font, R., Karcher, C., Reche, X., Carmona, G., Tremps, V., & Irurtia, A. (2021b). Monitoring external load in elite male handball players depending on playing positions. Biology of Sport, 38(3), 3–9. doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2021.101123

[8] Ghobadi, H., Rajabi, H., Farzad, B., Bayati, M., & Jeffreys, I. (2013). Anthropometry of world-class elite handball players according to the playing position: Reports from men’s handball world championship 2013. Journal of Human Kinetics, 39(1), 213–220. doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2013-0084

[9] Gorostiaga, E. M., Granados, C., Ibáñez, J., & Izquierdo, M. (2005). Differences in Physical Fitness and Throwing Velocity Among Elite and Amateur Male Handball Players. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 26(3), 225–232. doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-820974

[10] Gorostiaga, E. M., Izquierdo, M., Iturralde, P., Ruesta, M., & Ibáñez, J. (1999). Effects of heavy resistance training on maximal and explosive force production, endurance and serum hormones in adolescent handball players. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology, 80, 485–493. doi.org/10.1007/s004210050622

[11] Harriss, D. J., & Atkinson, G. (2015). Ethical standards in sport and exercise science research: 2016 update. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 36(14), 1121–1124. doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1565186

[12] Ingebrigtsen, J., Jeffreys, I., & Rodahl, S. (2013). Physical characteristics and abilities of junior elite male and female handball players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 27(2), 302–309. doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e318254899f

[13] Irurtia, A., Busquets, A., Carrasco, M., Ferrer, B., & Marina, M. (2010). Control de la flexibilitat en joves gimnastes de competició mitjançant el mètode trigonomètric: un any de seguiment (Flexibility resting in young competing gymnasts using a trigonometric method: one-year follow-up). Apunts Medicina de l’Esport, 45(168), 235–242.

[14] Karcher, C., & Buchheit, M. (2014). On-Court demands of elite handball, with special reference to playing positions. Sports Medicine, 44(6), 797–814. doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0164-z

[15] Krüger, K., Pilat, C., Ückert, K., Frech, T., & Mooren, F. C. (2014). Physical performance profile of handball players is related to playing position and playing class. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(1), 117–125. doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e318291b713

[16] Lidor, R., Falk, B., Arnon, M., Cohen, Y., Segal, G., & Lander, Y. (2005). Measurement of talent in team handball: The questionable use of motor and physical tests. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 19(2).

[17] Malina, R. M., Rogol, A. D., Cumming, S. P., Coelho E Silva, M. J., & Figueiredo, A. J. (2015). Biological maturation of youth athletes: assessment and implications. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(13), 852–859. doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-094623

[18] Manzi, V., D’Ottavio, S., Impellizzeri, F., Chaouachi, A., Chamari, K., & Castagna, C. (2010). Profile of weekly training load in elite male professional basketball players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 18(3), 675–684. doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d7552a

[19] Martínez-Rodríguez, A., Martínez-Olcina, M., Hernández-García, M., Rubio-Arias, J., Sánchez-Sánchez, J., & Sánchez-Sáez, J. A. (2020). Body composition characteristics of handball players: systematic review. Archivos de Medicina Del Deporte, 37(1), 52–61.

[20] Massuça, L., Branco, B., Miarka, B., & Fragoso, I. (2015). Physical fitness attributes of team-handball players are related to playing position and performance level. Asian Journal of Sports Medicine, 6(1), 2–6. doi.org/10.5812/asjsm.24712

[21] Matthys, S. P. J., Fransen, J., Vaeyens, R., Lenoir, M., & Philippaerts, R. (2013a). Differences in biological maturation, anthropometry and physical performance between playing positions in youth team handball. Journal of Sports Sciences, 31(September 2014), 1344–1352. doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2013.781663

[22] Matthys, S. P. J., Vaeyens, R., Fransen, J., Deprez, D., Pion, J., Vandendriessche, J., Vandorpe, B., Lenoir, M., & Philippaerts, R. (2013b). A longitudinal study of multidimensional performance characteristics related to physical capacities in youth handball. Journal of Sports Sciences, 31(3), 325–334. doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.733819

[23] Matthys, S. P. J., Vaeyens, R., Vandendriessche, J., Vandorpe, B., Pion, J., Coutts, A. J., Lenoir, M., & Philippaerts, R. M. (2011). A multidisciplinary identification model for youth handball. European Journal of Sport Science, 11(5), 355–363. doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2010.523850

[24] Matthys, S., Vaeyens, R., Coelho e Silva, M., Lenoir, M., & Philippaerts, R. (2012). The contribution of growth and maturation in the functional capacity and skill performance of male adolescent handball players. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 33, 543–549. doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1298000

[25] Michalsik, L. B., & Wagner, H. (2021). Physical testing in elite team handball: Specific physical performance vs. general physical performance. Digitalization and Technology in Handball - Natural Sciences/The Game/Humanities. The Sixth International Conference on Science in Handball.

[26] Mohamed, H., Vaeyens, R., Matthys, S., Multael, M., Lefevre, J., Lenoir, M., & Philppaerts, R. (2009). Anthropometric and performance measures for the development of a talent detection and identification model in youth handball. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27(3), 257–266. doi.org/10.1080/02640410802482417

[27] Mónaco, M., Gutiérrez Rincón, J. A., Montoro Ronsano, B. J., Whiteley, R., Sanz-Lopez, F., & Rodas, G. (2019). Injury incidence and injury patterns by category, player position, and maturation in elite male handball elite players. Biology of Sport, 36(1), 67–74. doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2018.78908

[28] Oliveira, T., Abade, E., Gonçalves, B., Gomes, I., & Sampaio, J. (2014). Physical and physiological profiles of youth elite handball players during training sessions and friendly matches according to playing positions. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 14(1), 162–173. doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2014.11868712

[29] Ortega-Becerra, M., Belloso-Vergara, A., & Pareja-Blanco, F. (2020). Physical and Physiological Demands during Handball Matches in Male Adolescent Players. Journal of Human Kinetics, 72(1), 253–263. doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2019-0111

[30] Rivilla-Garcia, J., Grande, I., Sampedro, J., & Van Den Tillaar, R. (2011). Influence of opposition on ball velocity in the handball jump throw. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 1;10(3):534–9 .

[31] Schwesig, R., Hermassi, S., Fieseler, G., Irlenbusch, L., Noack, F., Delank, K. S., Shephard, R. J., & Chelly, M. S. (2017). Anthropometric and physical performance characteristics of professional handball players: Influence of playing position. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 57(11), 1471–1478. doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.16.06413-6

[32] Wagner, H., Orwat, M., Hinz, M., Pfusterschmied, J., Bacharach, D. W., von Duvillard, S. P., & Müller, E. (2016). Testing Game-Based Performance in Team-Handball. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(10), 2794–2801. doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000580

[33] Winter, E. M., & Maughan, R. J. (2009). Requirements for ethics approvals. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27(10), 985–985. doi.org/10.1080/02640410903178344

[34] Zapartidis, I., Vareltzis, I., Gouvali, M., & Kororos, P. (2009). Physical Fitness and Anthropometric Characteristics in Different Levels of Young Team Handball Players. The Open Sports Sciences Journal, 2,22-28. dx.doi.org/10.2174/1875399X00902010022

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: X, XXX 2024

Accepted: XX, XXXXXX 2024

Published: 1, April 2025

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en