Service-Learning and Motor Skills in Initial Teacher Training: Doubling Down on Inclusive Education

*Corresponding author: María Maravé-Vivas marave@uji.es

Cite this article

Maravé-Vivas, M., Salvador-García, C., Capella-Peris, C. & Gil-Gómez, J. (2023). Service-Learning and Motor Skills in Initial Teacher Training: Doubling Down on Inclusive Education. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 152, 82-89. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2023/2).152.09

Summary

The diversity present in classrooms requires teachers to be prepared to provide an adequate educational response to all students. However, in the field of Physical Education, teachers do not feel adequately prepared to work with students with functional diversity. Initial teacher training is essential in moving towards inclusive motor sessions, and more research is needed to analyse what practices can improve training in this regard. This study examined how participation in a service-learning programme developed future teachers’ knowledge of inclusive education. The participating students were taking a subject in the field of motor skills and body expression as part of the Early Childhood Education Teacher Training Degree, and designed and implemented sessions aimed at children with functional diversity. This research was approached through a qualitative research design by analysing reflective notebooks. The results reveal that service-learning applied in the field of training future teachers through Physical Education is a suitable tool for developing knowledge related to changing the vision of functional diversity, understanding the problems they face, challenging preconceived ideas and developing positive skills and attitudes. This knowledge enhances their education and is highly relevant if inclusive education is to be encouraged in the future.

Introduction

The diversity present in classrooms requires teachers to be prepared to provide an adequate educational response to all students, regardless of their differences. In this sense, if progress is to be made towards inclusive education, initial teacher training is crucial. With regard to students with functional diversity, different studies show that teachers do not feel adequately prepared to work with this group in the field of Physical Education (PE), highlighting the lack of initial training in this area (Apelmo, 2022; Tant & Watelain, 2016; Wilhelmsen & Sørensen, 2017). In this respect, the literature calls for more research aimed at developing teaching competences related to working with individuals with functional diversity in the field of PE and analysing which practices can improve the training of future teachers (Hernández et al., 2011; Hutzler et al., 2019).

In order to address these issues, service-learning (SL) emerges as a possibility, because there are different research studies in the field of PE providing a service to groups with functional diversity that offer relevant learning in order to advance towards educational inclusion, including technical learning and improving attitudes towards the group (Capella et al., 2014; Case et al., 2021). SL is an educational experience whereby students participate in service activities that benefit the community, and reflect on developing a greater understanding of content, personal values and civic responsibility (Bringle & Clayton, 2012). For practical purposes, SL is usually implemented within the framework of a specific subject and the students who take it apply subject-related learning in such a way that they improve skills and attitudes in the academic, social, personal and civic spheres.

Butin (2003) identifies four major perspectives of learning generated by SL: technical, cultural, political and post-structural. This study focuses on the cultural perspective, which includes the knowledge developed by students in relation to a greater understanding of the group with which they work. In other words, by interacting with the context and the target group, learners generate an understanding of their needs and challenges which promotes a better understanding of society. This shared experience could lead to an improvement in university students’ skills and attitudes regarding inclusive education (McCracken et al., 2020). Following the aforementioned model and within the field of PE, Gil-Gómez et al. (2015) provide an extension of the subcategories that comprise the cultural learning dimension: (1) understanding diversity issues and (2) diversity as a source of learning. The aim of this study is to analyse knowledge related to the cultural perspective developed by university students after participating in an SL programme.

Methodology

Research design

This research was undertaken using a qualitative research design (Flick, 2015), which aims to understand the complexity of social phenomena based on the perspective of its participants (Pérez-Juste et al., 2012), as it allows for a holistic and in-depth analysis of a phenomenon in this context (Yin, 2009).

Participants

The participants (N = 123) were part of a regular group formed by the group-class in the subject “Fundamentals of Body Expression; Motor Games in Early Childhood Education” on the Degree in Early Childhood Education Teaching at the Jaume I University.

Resources

The research instrument used was the reflective monitoring notebook, a well-established tool in SL research (Chiva-Bartoll et al., 2020). It consisted of a group and an individual component, which all students had to complete during the project. The group part recorded both the body expression activities and motor games carried out in each session and the modifications that were introduced in their practice. The individual section included reflections related to their experience and learning related to personal skills (vision on diversity, civic and social skills put into play…).

Context of application

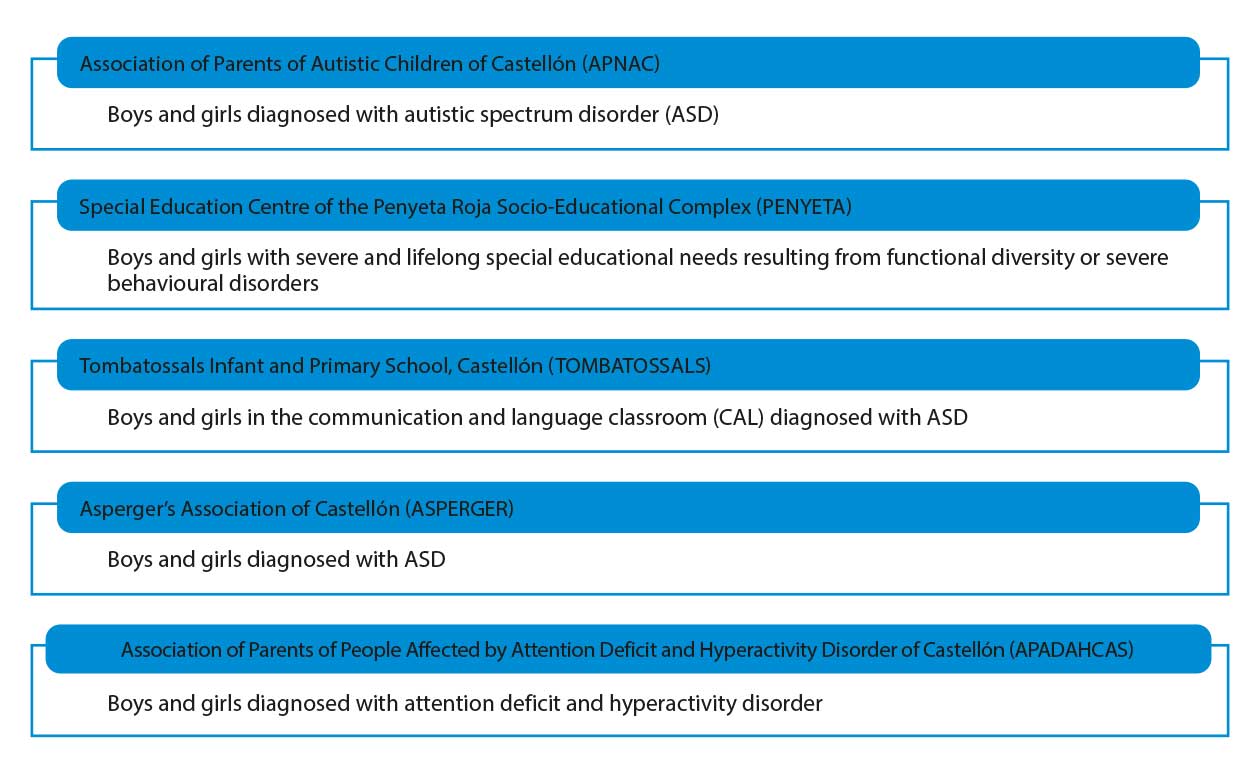

The SL programme was developed in collaboration with organisations from the socio-educational network of the city of Castellón de la Plana (Figure 1) that cater for groups of children with different disorders, all with motor, social and communicative impairments.

It should be pointed out that the service provided resulted from the lack of recreational and sporting activities aimed at children with functional diversity, both in the public and private spheres, in which they can be adequately cared for and which provide a space for improvement (non-clinical) in the areas they are affected by.

SL Programme

The general SL programme was implemented in the subject “Fundamentals of Body Expression; Motor Games in Early Childhood Education”. This subject works on content related to corporal expression, motor skills and play, which are included in the curriculum of the second cycle of the Infant Education programme.

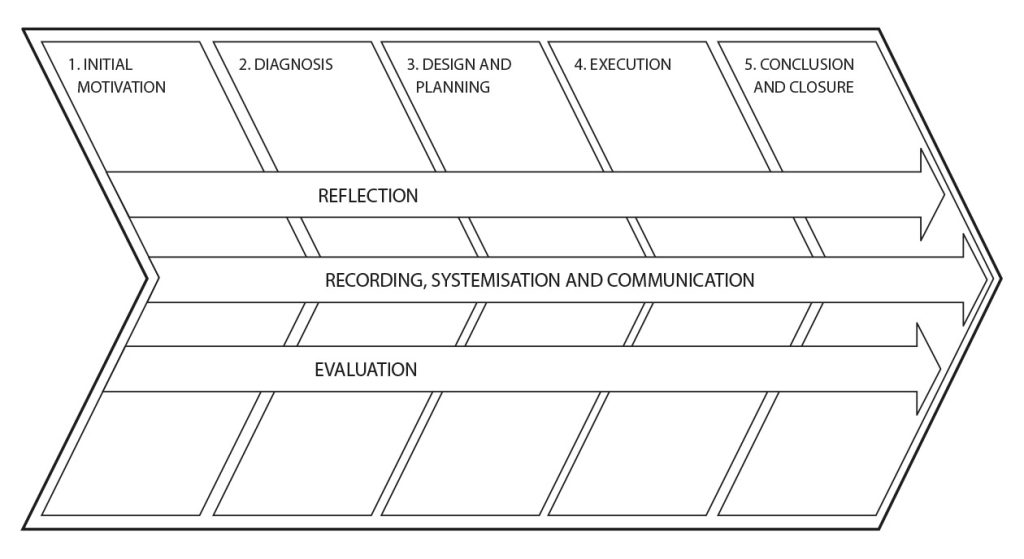

The students were organised into working groups of four to six members in order to design and implement game sessions and corporal expression activities aimed at improving the motor and socialisation skills of the participating children. In order for an SL project to develop properly, it is important to follow predetermined phases. Each group developed a project on a reference entity following the model (Figure 2) proposed by CLAYSS (2016). Within the assessment system of the subject, the SL project is included in the section on the preparation and/or presentation of work, with a weight of 30% of the total mark.

In the diagnosis stage, each group detected the motor and corporal expression needs presented by the specific group of their reference entity. These contents had been previously worked on in class, both theoretically and practically.

As can be seen in the figure, reflection should be encouraged transversally throughout the process, as it contributes decisively to consolidating and deepening learning. The reflection system carried out is summarised below:

- Group tutorials. The university faculty guided the students through group tutorials, reviewed their work and shared some feedback.

- Post-session reflection. At the end of each session, the group had to carry out a final, shared reflection, in which the staff of the organisation and the university teaching staff could also participate.

- Group reflections in the university classroom. Each group shared their experiences in leading the PE sessions in the entities.

- Reflective monitoring notebook. Students had to fill this in throughout the whole process and hand it in at the end.

Statistical Analysis

This research was approached using the interpretative paradigm and took the research of Gil-Gómez et al. (2015), who identified two categories for cultural dimension (understanding the problems of diversity and diversity as a source of learning), which are analysed in this study, as a reference.

The information analysis was carried out through a multi-phase approach, based on an initial phase of open coding and a second phase of axial coding, from which different subcategories were created. The reflection notebooks were anonymised and coded for analysis based on the entity in which the SL was conducted and the number of the notebook from which each fragment was extracted. For example, (APNAC_3). In addition, ethical criteria specific to the research were followed, including the collection of informed consent, researcher triangulation and member checking (Flick, 2015).

Results

This section presents the results related to the cultural perspective (Butin, 2003) following the categories proposed by Gil-Gómez et al. (2015). Examples of quotations are provided to demonstrate the learning acquired through the textual transcription extracted from the notebooks. The selection of quotes was based on relevance (comments of most interest in relation to the research objectives) and depth (focus on comments that reflect the most insight into the respondents’ thoughts/ideas regarding their experiences).

The first category addresses the understanding of diversity issues, which reflects the personal learning that emanates from understanding the characteristics of children with functional diversity. This category was grouped into the subcategories: capacities and interests of the collective, legitimate needs and aspirations.

In this sense, after the games and corporal expression sessions, the pupils understood that the spectrum is very broad and, although they share similarities, each child has different interests, motivations, abilities, characteristics… that make a personalised response necessary.

“It’s true that autistic children are very different from each other, they share very few similarities, each one has different interests and you can’t use the same resources to calm them down, for example. You can hug some of them to calm them down, but others don’t like contact and it wouldn’t be appropriate, it would be better to take them to a quiet place.” (APNAC_3)

As the sessions developed, they realised the importance of working on the basis of their interests in order to achieve the proposed didactic objectives and, consequently, they modified their sessions to include their interests and likes.

“As the sessions went on, we adapted the activities to suit each of them, based on their interests. For example, in order for X to do the activities, you had to play music for him.” (APNAC_4)

On the other hand, they became aware of the problems or repercussions that can arise as a result of preconceived ideas, expectations or social prejudices about this group. Thus, they also alluded to the change in these expectations.

“Working with students with special educational needs has made me realise that we should not label children or prejudge them, as having certain expectations of them only limits them. Furthermore, any expectation you have of them is invalid, as they always surprise you and show you that, despite their disabilities, they can achieve more than we usually think, even with their limitations.” (PENYETA_10)

Thus, students pointed out that misinformation about functional diversity is one of the factors that cause preconceived ideas or prejudices and that this conditions their own attitudes and behaviours. This information is useful for teaching and can be extrapolated to any type of group.

“I am sure that the perception I have of this collective is the same one that society has, and it includes all the prejudices we have about what people with autism are like (…) Before doing the SL I thought that it would be very difficult to work with children with Asperger’s, that I wouldn’t understand them, that they would get angry most of the time, that they wouldn’t listen to me… When the time came for me to work with them, I realised that all my concerns were unfounded.” (ASPERGER_10)

In another area, the students became aware of the needs that may arise in relation to their care and attention.

“It seems to me that for families and close friends (…) it must be a very hard and sacrificial way of life, they have to be very strong people to endure so much, not only the extra work they are able to do, but also emotionally.” (ASPERGER_8)

Finally, students developed learning related to the legitimate aspirations of the collective. They reflected on the need to adapt the educational process to the students and not the other way around, a basic concept in the promotion of inclusive education.

“Now I know that if I have a student with Asperger’s in my classroom, I don’t have to separate him or her because I think that he or she cannot do the activities at the same pace as the rest, but I need to adapt the activities so that he or she can do them, just as I would do with the rest of the students. Since all pupils have different needs and learning paces, it is the teacher who has to adapt to the pupils and not the other way round.” (ASPERGER_10)

“In my capacity as the teacher I want to be, I do not entertain the idea of having to adapt a game for one child, no, what I would do is adapt the game for everyone. Things can be done without excluding anybody. Games for all. For this reason, I think it is necessary to focus on inclusive education that addresses all the specific characteristics of the classroom.” (TDAH_8)

By interacting with the group, the students understood that not only should their limitations be taken into account, but they also saw the importance of focusing on the capabilities of these individuals. In this sense, students consider that the aforementioned prejudices emerge as an obstacle in progressing towards inclusion.

“In my view it is our own prejudices that make their inclusion more difficult, as we only see their weaknesses and never what they excel in. I used to be like that, but after three months at Penyeta Roja, I discovered that yes, they might have difficulties in some academic tasks, but I met students who excelled in painting, swimming or gardening. And this is what we have to focus on (…) their multiple skills and not their weaknesses, which is something we all have, regardless of whether we have functional diversity or not.” (PENYETA_2)

The second category is called “diversity as a source of learning”. This encompasses different personal knowledge that the future teachers have gained in relation to the diversity present in the sessions.

Given the breadth of types of learning that can be developed within this category, the following subcategories were grouped together: teaching competence, enriching diversity and social and educational inclusion.

In the first category, learning related to teaching competence is included. The students valued learning developed as a result of interaction with the group, as they considered that it will be useful in their future.

“It has been an experience that will be very useful for me in the future when dealing with children and for understanding the basic guidelines on how to react if any of them have these difficulties.” (APNAC_3)

After their experience, they realised that, given the diversity in the classroom, it is essential that they are trained and prepared to be able to provide an adequate educational response for all students, regardless of their abilities and characteristics.

“This opportunity has helped me to understand that when I work as a teacher in the classroom I will have students with many different abilities and limitations, since each child is different and has his or her own needs, so it is very important that I start training, researching, practising, etc.” (APNAC_11)

Secondly, learning related to the recognition of diversity as beneficial is grouped together. As a result of the experience, the students reflected on the differences between individuals and developed a concept of diversity that is considered positive and beneficial, as well as a source of learning. This led them to further deepen their understanding of the characteristics, needs, etc. of the group and thus improve their understanding of diversity and society.

“It has helped me a lot to better understand people with educational difficulties and to appreciate differences as something positive for learning. In the future, whether I work with pupils with educational support difficulties or pupils in mainstream schools, I know that I will know how to use the differences between them as another educational tool.” (PENYETA_1)

“I have seen, through this experience, that there are big differences between individuals, but this is what enriches us as individuals and as a society. We are all different, but we are all people with rights and we can all learn a lot from this great diversity.” (PENYETA_6)

Moreover, university students became aware that it is necessary to see the learner instead of the diagnosis. This issue is relevant in teaching, as such a diagnosis may be accompanied by preconceived ideas.

“I have learned not to pay attention to whether a child has ADHD or not (referring to not labelling and having different expectations); when I was working on the project I only saw children, some of them requiring more activity, some of them less activity, etc.” (TDAH_2)

Finally, derived from the positive conception and consideration of diversity as a learning tool, references relating to social and educational inclusion were brought together. The students considered that the way to avoid exclusion is through coexistence. They concluded that, in order to teach values or behaviours, real interaction is need to develop meaningful learning.

“I think it would be very positive for both disabled and non-disabled children to be able to coexist and learn from each other. I find it very difficult to try to teach them what it means not to discriminate against people because of their different characteristics if they don’t have the opportunity to encounter them. I believe that discrimination arises from fear of the unknown and ignorance; we should try to ensure that in our classrooms children can share experiences with other children and learn to get to know them, to really understand that diversity is not negative but positive.” (PENYETA_2)

Students felt that schools should interact, so that “neurotypical” students become aware that all people have rights and should therefore have equal opportunities.

“I think it is essential that, from an early age, pupils with a disability interact with others who are neurotypical because the latter realise that we are all equal and we all have the same rights and that we should all have the same opportunities.” (TOMBATOSSALS_5)

Discussion

This study attempts to respond to one of the courses of action proposed by Hernández et al. (2011), who call for the implementation of teacher training programmes that allow for an approach to adapted and inclusive motor practice, while analysing the learning generated through it. The interest in the object of study is reflected in the increase of studies related to inclusion in PE (Marín-Suelves & Ramón-Llin, 2021).

The literature in the field of PE indicates that there is a lack of training, knowledge and experience regarding attention to diversity (Apelmo, 2022) and, in fact, teachers indicate that they do not feel adequately prepared with regard to educational inclusion, highlighting insufficient initial training in this regard (Tant & Watelain, 2016; Wilhelmsen & Sørensen, 2017). Clearly, a change in initial teacher education aimed at improving inclusive education is necessary (Apelmo, 2022).

In this sense, the SL programme presented in this study seems to have been a good way to start encouraging this change, as it has combined both academic preparation and experiences through which university students have been able to interact directly with children with functional diversity; key factors in the construction of positive attitudes towards inclusion (Hernández et al., 2011; Van Mieghem et al., 2018). Therefore, SL emerges as an appropriate way to improve attitudes towards individuals with functional diversity among trainee teachers (Case et al., 2021).

The first category analysed presents student learning related to the understanding of diversity issues. Previous literature on SL applied in the field of motor skills has already highlighted its contribution to bringing about changes in perceptions, understandings and beliefs about the target group (Seban, 2019). The results of the present study indicate that the participating trainees were able to perceive that the motivations, interests, characteristics and abilities of the children they worked with needed personalised responses. At the same time, according to Ashton and Arlington (2019), this increased understanding of diversity could increase self-confidence in working with diverse learners in their future teaching. Moreover, university students have become aware of the impact that social prejudices can have, as they can reinforce the assumption of negative stereotypes. In this way, it appears that the SL programme has led to an improvement in university students’ attitudes towards inclusion and inclusive practices through direct experience (McCracken et al., 2020).

Another relevant aspect of learning within this category is understanding the legitimate aspirations of the groups targeted, as PE teachers sometimes prefer segregated classes, i.e. separate provision for pupils with special educational needs (Slee, 2018), which has a negative impact on the motor experiences of these children (Apelmo, 2022). In this sense, therefore, the SL programme seems to have helped trainee teachers to realise the need to tailor the educational process to the learners, a key aspect in promoting inclusive education. Similarly, university students appear to have reconfigured their view of diversity by shifting from a focus on limitations to a focus on the capabilities of the children they have worked with; demonstrating an appreciation for the multiple ways of moving, being healthy and physically active and showing a strong commitment to this diversity, issues that are also required to support inclusive (physical and motor) education (Apelmo, 2022; Penney et al., 2018).

The second category analysed deals with university students’ perceptions of diversity as a source of learning. This is key, as a lack of teacher training on inclusion leads to the perception of diversity as a problem, and so risks seeing children with special educational needs as separate from the rest, thus tending to marginalise them (Apelmo, 2022). In this sense, Gil-Gómez et al. (2015) argue that SL is capable of generating learning of various kinds in those who implement it, including aspects such as improved teaching competence, the perception of diversity as a source of benefit and an improvement in social and educational inclusion, the three subcategories to which the students participating in our study alluded.

Increasing teaching competence is relevant since, when specialist PE teachers do not feel sufficiently prepared to deal with diversity, they tend to become frustrated, nervous and frightened when they encounter students with special educational needs in class (Apelmo, 2022). Therefore, being able to develop inclusive practices with the guidance and mentoring of the university faculty (through SL) can not only enhance the development of teaching competence, but also provide teaching experiences that can reshape views on inclusion and develop greater self-confidence in working with children with special educational needs (Ashton & Arlington, 2019; Van Mieghem et al., 2018). In this way, SL emerges as an ideal tool in the construction of a remodelled motor and physical education, which is committed to educational inclusion and which perceives differences in bodies and minds as a source of learning (Apelmo, 2022). Ultimately, SL is a potentially appropriate method by which to support inclusive education, as it enables trainee teachers to gain a new perspective on the educational experience by promoting attitudes, values and practices that support inclusive educational approaches in schools (Carrington et al., 2015).

Conclusions

It is necessary to address initial teacher training if progress is to be made towards inclusive education. After participating in the SL programme, students have altered and developed their view of functional diversity, better understanding the issues they face, challenging preconceived ideas, developing skills and positive attitudes towards diversity and the group.

On the one hand, the results obtained suggest that the participating students have developed knowledge that will be of great help to them in their professional future to promote inclusive education, in line with the general literature on SL (Carrington et al., 2015).

On the other hand, the novelty of the present research lies in the fact that SL applied in the specific field of PE is postulated as an appropriate tool for improving initial teacher training in relation to the group with functional diversity, in line with the needs identified in the literature in this field (Hernández et al., 2011; Hutzler et al., 2019).

However, limitations of the study could be identified regarding the specificity of the environment, situation and sample in which the research was carried out, making it difficult to transfer the results to other educational contexts, and the lack of variety in the data collection strategy, which restricts the consistency of the findings presented. Taking this information into account, as future research prospects, it is proposed that multiple case studies be carried out, as well as the triangulation of the information obtained with other agents involved in the programme and/or instruments. In addition, the results obtained in this study may encourage the research team to gather more data to further the objective of the study.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this work acknowledge and thank the participation of the entities involved in the programme, especially the children, their families and the participating university students.

Acknowledgements and funding

The authors would like to thank the support provided by the research project UJI-A2017-03 (Institutional Review Board of the Jaume I University), by the research promotion plan (PREDOC/2016/53) and especially by all the participants.

References

[1] Apelmo, E. (2022). What is the problem? Dis/ability in Swedish physical education teacher education syllabi. Sport, Education and Society, 27(5) 529-542. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1884062

[2] Ashton, J. R., & Arlington, H. (2019). My fears were irrational: Transforming conceptions of disability in teacher education through service learning. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 15(1), 50-81.

[3] Bringle, R. G., & Clayton, P. H. (2012). Civic education through service learning: What, how, and why? In L. Mcilrath, A. Lyons & R. Munck (Eds.) Higher education and civic engagement: Comparative perspectives (pp. 101-124). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

[4] Butin, D. W. (2003). Of What Use Is It? Multiple Conceptualizations of Service Learning Within Education. Teachers College Record, 105(9), 1674-1692. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-9620.2003.00305.x

[5] Capella, C., Gil-Gómez, J., & Martí-Puig, M. (2014). La metodología del aprendizaje-servicio en la educación física. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 116(2), 33-43. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2014/2).116.03

[6] Carrington, S., Mercer, K., Iyer, R., & Selva, G. (2015). The impact of transformative learning in a critical service-learning program on teacher development. Reflective Practice, 16(1), 61-72. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2014.969696

[7] Case, L., Schram, B., Jung, J., Leung, W., & Yun, J. (2021). A meta-analysis of the effect of adapted physical activity service-learning programs on college student attitudes toward people with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(21) 2990-3002. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1727575

[8] Chiva-Bartoll, Ò., Capella-Peris, C., & Salvador-Garcia, C. (2020). Service-learning in physical education teacher education: Towards a critical and inclusive perspective. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(3), 395-407. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1733400

[9] CLAYSS (2016). Manual para docentes y estudiantes solidarios. Edición Latinoamericana. Buenos Aires: CLAYSS.

[10] Flick, U. (2015). Qualitative Research in Education. Madrid: Ediciones Morata.

[11] Furco, A., & Billig, S. H. (2002). Service-Learning: The essence of pedagogy. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

[12] Gil-Gómez, J., Chiva-Bartoll, Ó., & Martí-Puig, M. (2015). The impact of service learning on the training of pre-service teachers: Analysis from a physical education subject. European Physical Education Review, 21(4), 467-484. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X15582358

[13] Hernández Vázquez, F. J., Casamort Ayats, J., Bofill Ródenas, A., Niort, J., & Blázquez Sánchez, D. (2011). Physical Education Teachers Attitudes to Inclusive Education: A Review. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 103, 24-30. https://revista-apunts.com/ca/les-actituds-del-professorat-deducacio-fisica-cap-a-la-inclusio-educativa-revisio/

[14] Hutzler, Y., Meier, S., Reuker, S., & Zitomer, M. (2019). Attitudes and self-efficacy of physical education teachers toward inclusion of children with disabilities: a narrative review of international literature. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(3), 249-266. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2019.1571183

[15] Marín-Suelves, D., & Ramón-Llin, J. (2021). Physical Education and Inclusion: a Bibliometric Study. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 143, 17-26. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2021/1).143.03

[16] McCracken, T., Chapman, S., & Piggott, B. (2020). Inclusion illusion: a mixed-methods study of preservice teachers and their preparedness for inclusive schooling in Health and Physical Education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2020.1853259

[17] Penney, D., Jeanes, R., O’Connor, J., & Alfrey, L. (2018). Re-theorising inclusion and reframing inclusive practice in physical education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(10), 1062-1077. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1414888

[18] Pérez-Juste, R., Galán, R., & Quintanal, J. (2012). Métodos y diseños de investigación en educación. Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia.

[19] Seban, D. (2019). Faculty perspectives of community service learning in teacher education. Çukurova University Faculty of Education Journal, 42(2), 18-35. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/cuefd/issue/4136/54290

[20] Slee, R. (2018). Inclusive Education Isn’t Dead, It Just Smells Funny. New York: Routledge.

[21] Tant, M., & Watelain, E. (2016). Forty Years Later, a Systematic Literature Review on Inclusion in Physical Education (1975-2015): A Teacher Perspective. Educational Research Review, 19, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2016.04.002

[22] Van Mieghem, A., Verschueren, K., Petry, K., & Struyf, E. (2020). An analysis of research on inclusive education: a systematic search and meta review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(6), 675-689. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1482012

[23] Wilhelmsen, T., & Sørensen, M. (2019). Physical education-related home-school collaboration: The experiences of parents of children with disabilities. European Physical Education Review, 25(3), 830-846. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X18777263

[24] Yin, R.K. (2009). Case Study Research: Design and Methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: June 3, 2022

Accepted: October 14, 2022

Published: April 1, 2023

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en