Player Defaults in Professional Tennis Tournaments for Men From 1973 to 2024

*Corresponding author: Rodrigo Ampuero rod.ampuero12@gmail.com

Cite this article

Casals, M., Peña, V., Martínez, J. A., Ampuero, R., Cortés, J., & Baiget, E. (2025). Player defaults in professional tennis tournaments for men from 1973 to 2024. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 163, 47-57. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2026/1).163.05

Abstract

In tennis, there are different types of situations in which players are unable to finish a match. Defaults refer to a player’s disqualification for violating the conduct code during or before a match. This study describes defaults in ATP tournaments from 1973 to 2024, analyzing epidemiological patterns. The incidence proportion (IP) per 1,000 matches was 0.59 (95% CI: 0.48-0.71) before the match and 0.31 (95% CI: 0.23-0.39) during the match. The highest IP before the match occurred in 250 or 500 tournaments (IP: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.68-1.01) and on carpet surfaces (IP: 2.23; 95% CI: 1.59-3.05). Preliminary rounds and finals had IPs of 0.64 (95% CI: 0.51-0.79) and 0.74 (95% CI: 0.45-1.14), respectively. During matches, Masters and 250 or 500 tournaments had the highest IPs of 0.33 (95% CI: 0.15-0.63) and 0.33 (95% CI: 0.24, 0.45), respectively. Carpet courts showed again higher defaults (IP: 0.40; 95% CI: 0.16-0.82). These findings highlight the impact of tournament level, surface, and round on defaults.

Introduction

Tennis players require extensive dedication to the sport, addressing both mental and physical essential aspects. This long-term, complex process highlights the importance of considering mental health for achieving high-level performance, especially regarding factors related to competitiveness and stress (Crespo & Reid, 2007; Gucciardi et al., 2015; Harris et al., 2021). Recent studies have proven that professional tennis players show an important increase in obsessive-compulsive symptoms, which may be related to the intense training and strict daily routines required for high performance. These psychological vulnerabilities, although initially adaptative, may evolve during times of adversity and may be reflected on their behavior on-court (Marazziti et al., 2021). During the competition, psychological factors such as decision-making ability, emotional control, self-confidence, and willpower, come constantly into play with varying intensity according to the game’s evolution. These cognitive aspects and technical-tactical-physical abilities are fundamental to facing different situations as a professional player (Rodríguez & García, 2014). Mentally strong tennis players can maintain focus and self-talk aimed at intense emotional regulation, enabling them to better control stressful situations (Fritsch et al., 2020). Ineffective management of pressure and stress could lead to negative emotional reactions, which could influence their performance.

In tennis, there are different types of situations in which players are unable to finish a match or a tournament, having different consequences, as noted in Table S1 in the Supplementary Material. Defaults refer to a player’s disqualification for violating the conduct code during a match, or to total retirement from all events due to such a violation during the tournament but not in a match (ATP, 2024). Defaults during a match may be associated with the psychological factors mentioned above, which are strongly related to the management of critical moments during matches (Houwer et al., 2017). Defaults before the match (disqualifications occurring before the match starts) are of a more heterogeneous nature. A player’s disqualification (as during a match) can be associated with psychological factors linked to stress and self-control (Englert, 2016; Tossici et al., 2024), but defaults before the match can also be due to other causes, such as doping, betting, the player not being dressed or equipped in a professional manner, or a default for lack of punctuality (Fletcher, 2024; TADP rules, 2024). According to the penalty regulations, the first conduct violation during a match results in a warning, the second in a point-loss penalty, and each subsequent sanction after the third carries a game penalty. Nevertheless, after the third code violation, the ATP supervisor will assess whether each additional infraction will constitute a default that is definitive and not subjected to appeal (ATP, 2024; International Tennis Federation, 2023). As for the consequences of default, in accordance with Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) regulations, a disqualified or withdrawn player forfeits all prizes and points earned in that tournament event, in addition to receiving a financial penalty (ATP, 2024).

Among the most notorious cases of default during a match in tennis history is the case of Novak Djokovic who was disqualified from the 2020 US Open tournament during the fourth round for accidentally hitting a line judge with a ball. This disqualification allowed his opponent to advance to the next round without having to complete the match (Bodo, 2020). Also, at the 2009 US Open 2009, Serena Williams was disqualified in the semifinal against Kim Clijsters after threatening a line judge (Donegan, 2009). More recently, Russian player Andrey Rublev was defaulted from the 2024 Dubai Tennis Championship for yelling at a line judge (Reuters, 2024).

In the existing literature, different observational studies have shown an increase in the frequency of uncompleted matches—mainly due to injuries—among professional tennis players in recent years (Breznik & Batagelj, 2012; Maquirriain & Baglione, 2016; Montalvan et al., 2024; Okholm Kryger et al., 2015; Palau et al., 2024). However, to date, no studies have been published with the aim of describing and analyzing the factors associated with matches not completed due to defaults. Additionally, this type of disqualifying situation often attracts significant media attention, as the media frequently explore how and under what circumstances professional players exhibit this kind of behavior. Therefore, the aim of this study is to describe defaults in ATP tournaments between 1973 and 2024, analyse their epidemiological patterns, and identify possible associated factors. Given that defaults during a match are primarily linked to psychological factors such as stress management, whereas pre-match defaults have a broader set of causes, this research also provides a separate analysis of both types.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Sample

An observational, retrospective cohort study was conducted. A database of 186,224 matches from 1973 to 2024, containing information on ATP Tour tournaments, was used. The source was the GitHub repository https://github.com/JeffSackmann/tennis_atp, which compiles information from the official pages of various ATP tournaments (Table S2 in the Supplementary Material).

Variables

The outcome of interest was “Default” (Yes/No), which was further classified into “Default Before” (disqualification occurring before the match begins) and “Default During” (disqualification occurring during the match due to player conduct). The match- and tournament-related variables are detailed in Table S3 of the Supplemental material. In addition, the differences in age and ranking between players in each match was evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

Absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies were computed for categorical variables, while measures of central tendency and dispersion were calculated for continuous variables. A bivariate descriptive analysis was performed to characterize matches and players when a default occurred. The cumulative incidence or incidence proportion (IP) was calculated using the formula i = e/n, where e is the number of events (defaults) during the study period and n is the total number of exposed matches per 1,000 played matches. The IP of defaults was plotted across the range of years included in this study.

The number of defaults, the exposure as the number of matches, the IP, and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were provided for each category of relevant factors. In addition, following the STROBE statement for observational studies (Vandenbroucke et al., 2014) and the CONSORT statement for randomized controlled trials (Moher et al., 2010), relative and absolute measures of association between factors and the occurrence of defaults were provided. These were expressed as cumulative incidence ratio (CIR) and with their 95% CI and as risk difference (RD) with their 95% CI. CIR was estimated as the ratio of IPs between the two specified subgroups (i.e., clay vs. hard surface). Furthermore, the absolute measure of RD was calculated by subtracting the rates of the two exposure groups.

Measures of association were calculated with 95% CI. The significance level was set at α = .05.

All analyses were performed using version 4.1.3 of the R statistical software. The R package compareGroups (Subirana et al., 2014) was used to describe characteristics according to the occurrence of defaults. The epi.2by2 function of the R package epiR (Stevenson et al., 2024), with the setting method as cohort time, was used to calculate the incidence rates. The CIR was calculated using the function pois.exact from the epitools package. Most of the graphics were produced using the ggplot2package (Wickham, 2009). The reproducible code used in this study is available on a publicly accessible GitHub repository (https://github.com/marticasals/default_ATP/tree/main), allowing for the transparency and replicability of the statistical analysis.

Results

Exploratory Analysis of ATP Matches During the Period 1973-2024

181,239 (97.32%) out of 186,224 ATP matches studied were completed (Table 1). The median number of games per match was 22 (Q1:18-Q3:29). The majority of players were right-handed, both those who made it through the round (84.62%) and those who did not (84.56%). The median age difference between players was 3.35 years (Q1:1.39-Q3:5.59), and the median ranking difference was 46 positions (Q1:17-Q3:97).

Table 1

Frequency and percentage of each match according to tournament level, surface, sets, round, and match outcome

Descriptive Characteristics of Defaults

A total of 166 defaults were registered (0.09%), of which 109 (65.66%) occurred before the start of the match and 57 (34.34%) during play. The majority of defaults took place in 250 or 500 tournaments, with 105 (0.08%) occurring before the match and 42 (0.03%) during the match. Defaults were most common in preliminary rounds, with 85 (0.06%) before the match and 39 (0.03%) during the match. The IP of defaults was 0.89 per 1,000 matches (95% CI: 0.76-1.04), with 0.59 per 1,000 matches (95% CI: 0.48-0.71) occurring before the match and 0.31 per 1,000 matches (95% CI: 0.23-0.39) occurring during the match.

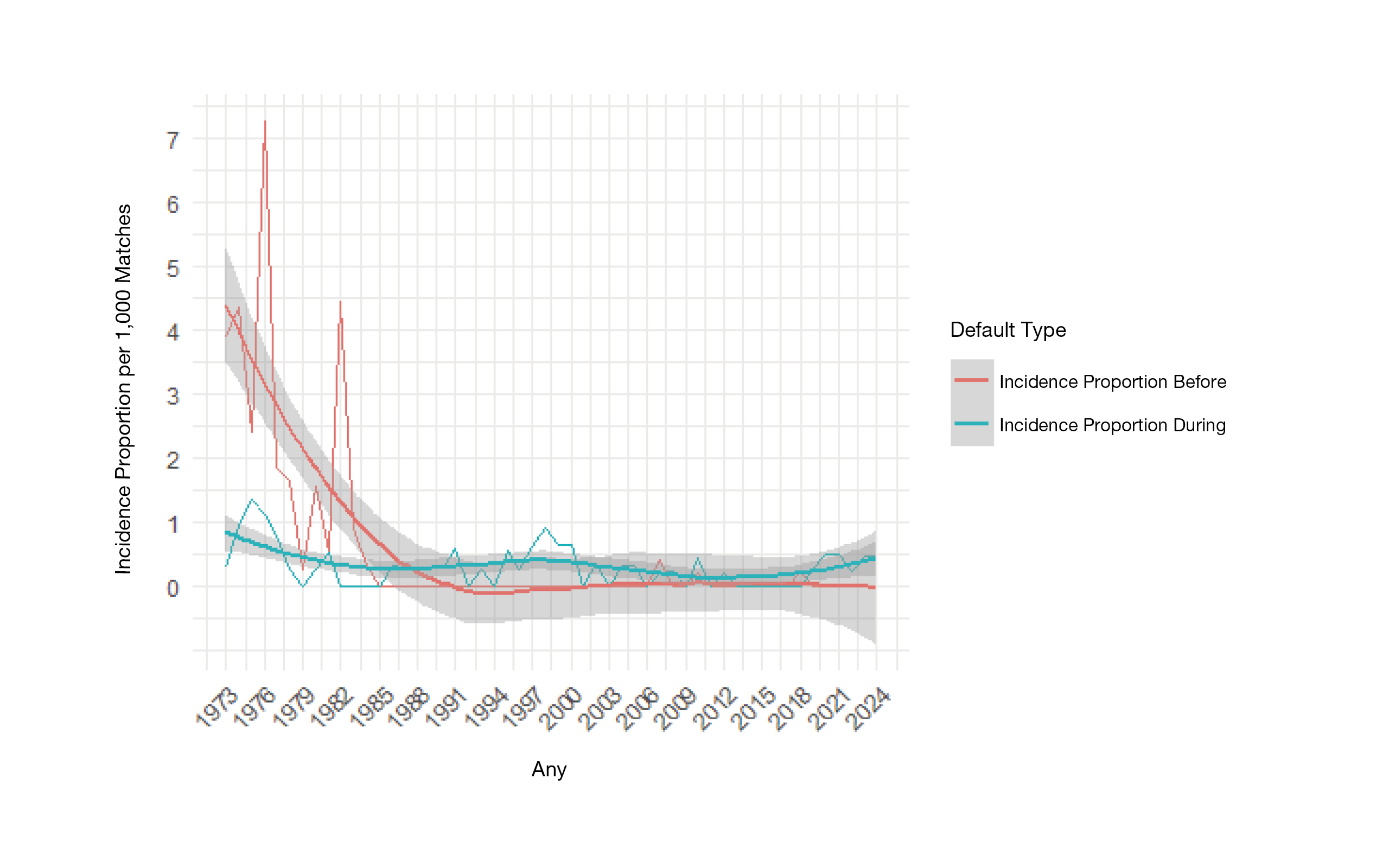

Figure 1 shows the trend in the incidence of defaults over time, differentiated by whether defaults occurred before or during the match. It can be observed that the incidence of defaults before the match was higher in the initial period, with a decreasing trend from 1973 to 1983 and a marked peak in 1976. The incidence of defaults during the match also followed a decreasing trend, albeit at a lower rate compared to defaults before the match. From the mid-1980s onwards, the IP for both types of defaults remained relatively constant over the years, with minor fluctuations.

Epidemiology Measures of Defaults

The highest IP of defaults before the match was registered in 250 or 500 tournament levels, with a value of 0.83 (95% CI: 0.68 – 1.01). Matches played on carpet surfaces had a significantly higher IP of defaults, at 2.23 (95% CI: 1.59-3.05), compared to those on clay courts, which had an IP of 0.63 (95% CI: 0.45-0.86). There was a significant increase in the risk of defaults on carpet surfaces compared to clay courts, with a CIR of 3.53 (95% CI: 2.28-5.48) and an RD of 1.60 (95% CI: 0.87-2.32). Regarding rounds, the preliminary rounds had an IP of 0.64 (95% CI: 0.51-0.79), while the finals had an IP of 0.74 (95% CI: 0.45-1.14) (Table 3).

Table 3

Incidence proportion (IP), cumulative incidence ratio (CIR), risk difference (RD) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of defaults before the match according to tournament level, surface, sets and round

The highest IP of defaults during the match was registered in Masters tournaments, with an IP of 0.33 (95% CI: 0.15-0.63), and in 250 or 500 tournament levels, with a value of 0.33 (95% CI: 0.24-0.45). Matches played on carpet surfaces had a higher IP of defaults, at 0.40 (95% CI: 0.16-0.82), compared to clay courts, which had a value of 0.26 (95% CI: 0.15-0.42). Preliminary rounds saw an IP of 0.29 (95% CI: 0.21-0.40), and finals had an IP of 0.48 (95% CI: 0.25-0.82) (Table 4).

Table 4

Incidence proportion (IP), cumulative incidence ratio (CIR), risk difference (RD) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of defaults during the match according to tournament level, surface, sets and round

Discussion

The objective of this study was to describe the defaults produced between 1973 and 2024 by analyzing 186,224 ATP Tour matches. It should be noted that, to our knowledge, there are no previous studies that analyze defaults in this context. Additionally, this study stratified the results by considering two distinct types of defaults: before and during the match. This stratification allows for a more nuanced understanding of the factors contributing to defaults and their respective impacts. Therefore, this investigation could serve as a starting point to analyze this understudied issue in tennis, which has also received considerable media attention in recent years (Lewis, 2023; Livaudais, 2024; Reuters, 2024; The Sydney Morning Herald, 2020). A very low IP value was noted due to the high-level players used in this investigation. More defaults were observed in best-of-3-sets matches and on carpet surfaces, with a high probability of being defaulted in advanced rounds (i.e., finals).

The IP of defaults was approximately 1 per 1,000 matches, mainly because of the quality of the sample (professional tennis players). With a strong mindset and sufficient emotional control, they can handle stressful and high-pressure situations properly. In addition, being defaulted has a multidirectional impact, including economic fines, loss of ranking points and—even—a negative self-image review. Our analysis also shows a decreasing trend in the incidence over the years. However, this trend has not always been constant; between 1970 and 1990, the proportion of defaults reached almost 7 per 1,000 matches. During this period, tennis faced behavioral problems both on- and off-court. In this environment, players such as Ilie Năstase, Jimmy Connors, and John McEnroe emerged, building their reputations around images of “bad boys” and exhibiting lower levels of sportsmanship, honesty, and courtesy toward officials (Lake, 2015).

Currently, just as with physical and technical preparation, psychological stress factors are better understood, and psychological preparation is much more specific. Many players work with sports psychologists who aim to help them deal with match pressure. This approach has significantly improved their ability to handle stressful situations on the court (Beckmann et al., 2021; Cowden et al., 2016; Pineda-Hernández, 2022). Additionally, with the increased level of professionalism among players over the years, there has been a clear trend toward a reduction in defaults related to issues such as not being dressed or equipped in a professional manner, or lack of punctuality.

The decreasing trend in the incidence over the years has been more prominent for defaults before a match than for defaults during a match, and both incidences have been similar since the mid-1980s. There is a growing demand for sports psychologists to help athletes overcome mental barriers and improve their performance (Weir, 2018), and as Walker et al. (2021) indicated, mental health problems affect everyone, including those who are among the best on the planet in terms of physical and sporting ability.

Defaults during a game are relatively rare events, but they are still present, even with a high level of professionalism and advances in mental health management. Further research should explore more deeply the complex interactions between mental health management, anger and aggressive or violent behavior during a game. In other sports, such as basketball, the National Basketball Association (NBA) teams began to incorporate sports psychologists at the beginning of the millennium. Now, the NBA requires all 30 teams to add, at a minimum, one full-time licensed mental health professional in the form of a psychologist or behavioral therapist (NBA’s Psychiatry Program, n.d.). In addition, in 2018, the NBA and the National Basketball Players Association announced that they had worked together to develop a mental wellness program for the league’s players (Aldridge, 2018). However, as Lev et al. (2022) found in their analysis of NBA Finals broadcast over twenty years, from 1998 to 2018, although the number of physical incidents decreased, symbolic violence increased starting in 2014, to the extent that symbolic incidents became more frequent than physical incidents. In fact, there are NBA players such as Jimmy Butler who have publicly admitted they want more brawls in the matches (Caparell, 2022).

Therefore, it seems there is a substratum of antisocial behavior in sports that is difficult to mitigate even with advances in mental preparation and psychological management (Kavussanu & Al-Yaaribi, 2019). As stated by Monaci & Veronesi (2018), in a sports competition, the principal characteristics for excelling are aggressiveness, dominance, competitive spirit—all stereotypically “male” features—. Monaci & Veronesi (2018) found in tennis that a competitive sport context activates the masculine dimension. This may be one explanation for why, in a sport such as tennis, with practically no physical interaction between opponents or among players and referees, “bad behavior” continues to be present (Monaci & Veronesi, 2018). Consequently, although the incidence of defaults during a match in tennis is low, and it has softly declined over time, it is still a matter of concern. For example, in 2022, 18-time Grand Slam winner Chris Evert stated she was worried about elite tennis players having “breakdowns” after a spate of angry, aggressive behavior (Martin, 2022). Kavussanu (as cited in University of Birmingham, 2022) suggests that the causes of this behavior are an individual’s values acquired at a young age by modeling the conduct of others in one’s social environment, such as parents, coaches, and peers. The researcher stresses the role of coaches and the way they interact with athletes as a key factor in instilling the value of respect for others and minimizing unsporting conduct. Furthermore, to mitigate this aggressive behavior, she proposes imposing significant consequences on players, such as increasing fines and even exclusion from future tournaments (University of Birmingham, 2022).

Defaults occurred more frequently in 3-set matches rather than in 5-set matches. These 5-set matches are played in the most important competitions throughout the year, called Grand Slams, in which the financial rewards, plus the number of ranking points possibly earned, may help explain why players avoid defaults at these tournaments. Regarding this, subsequent sanctions differ according to the type of tournament. For example, fines for unsportsmanlike actions are $30,000 for 250 tournaments and $40,000 for 500 tournaments, while the amount increases to $60,000 for Masters 1000 tournaments and $100,000 for Grand Slams (ATP, 2024). This suggests that players tend to avoid violating the code of conduct in tournaments where the penalties are more rigorous; therefore, these disqualifications occurred mostly at 250 or 500 tournaments, in which carpet surfaces are the most commonly used. Hence, defaults were related to carpet-surface matches showing the highest IP. This demonstrates a strong correlation between tournament level, sets played, game surface, and the default situation.

Moreover, players are more likely to receive a default in the final rounds rather than in the preliminary and qualifying rounds. As players advance through the rounds, the relevance of each match —and consequently the pressure of each one, as well as the cumulative pressure of the entire competition— significantly increases. Unlike in other sports, such as football, tennis players are restricted from communicating, interacting, or seeking guidance from their coaches or support personnel during competition, which adds another layer of pressure (Cowden et al., 2016). Probably for this reason, in the final rounds, situations of high psychological tension often occur, making it more likely for players to display inappropriate behaviors.

One important limitation of this research is the absence of specific reasons for defaults in the ATP archives, which restricts a deeper understanding of the nature of these defaults. However, this study underscores the critical need for better reporting and documentation of the causes of defaults. Improved reporting can facilitate future research, particularly in the area of mental health in tennis. The results of this study may be useful as practical guidance for ATP organizers, given the valuable causes mentioned that could possibly trigger defaults. This guidance should also involve referee staff, who are among the entities responsible for calling a default. A more comprehensive approach and understanding of these indicators may help referees anticipate when such situations are likely to occur. Furthermore, systematically recording and analyzing this information is essential for coaching staff, researchers, and, most importantly, for safeguarding health and well-being of the players. By addressing this gap, we can gain better insights into the factors contributing to defaults and develop targeted interventions to support players’ health and performance.

Conclusions

This is the first investigation ever carried out describing defaultsituations in professional tennis from 1973 to 2024 and analyzing incidence patterns and associated factors. The general IP is of very low value, probably due to the high level of the players. There is a decreasing trend in the incidence over the years, with a slight increase between 1970 and 1990. Defaults occurred more frequently in 3-set matches rather than in 5-set matches and at the 250 or 500 tournaments level. Carpet was the most common surface in which this disqualification occurred. There is a low probability of getting a default in preliminary and qualifying rounds. Consequently, tournament importance—considering round-played, prize money and ranking points to be earned—affects directly on defaults.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors wrote and critically reviewed the article. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Ethics Statement

No ethical approval was needed for carrying out this research, as all the information used and reported for analysis is freely available online.

Supplementary Material

Table S1

Nomenclature for Uncompleted Matches in Tennis and Their Impact. (Adapted from “The 2023 ATP Official Rulebook)

References

[1] Aldridge, D. (2018). NBA, NBPA taking steps to further address mental wellness issues for players. NBA.com. www.nba.com/news/morning-tip-nba-nbpa-addressing-mental-wellness-issues#/

[2] ATP. (2024). ATP Official Rulebook. ATP Tour. www.atptour.com/en/corporate/rulebook

[3] Beckmann, J., Fimpel, L., & Wergin, V. V. (2021). Preventing a loss of accuracy of the tennis serve under pressure. PLOS ONE, 16(7): e0255060. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255060

[4] Bodo, P. (2020). How Novak Djokovic was defaulted from the 2020 US Open–ESPN. ESPN. www.espn.com/tennis/story/_/id/29826438/how-novak-djokovic-was-defaulted-2020-us-open

[5] Breznik, K., & Batagelj, V. (2012). Retired Matches Among Male Professional Tennis Players. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 11(2), 270–278

[6] Caparell, A. (2022). Jimmy Butler Wants More Brawls in the NBA: ‘I Wish It Would Go Back to That Time’. Complex. www.complex.com/sports/a/adam-caparell/jimmy-butler-wants-more-brawls-in-nba

[7] Cowden, R. G., Meyer-Weitz, A., & Oppong Asante, K. (2016). Mental Toughness in Competitive Tennis: Relationships with Resilience and Stress. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00320

[8] Crespo, M., & Reid, M. M. (2007). Motivation in tennis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(11), 769–772. doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2007.036285

[9] Donegan, L. (2009). Serena Williams is fined $10,500 for US Open line judge tirade. The Guardian. www.theguardian.com/sport/2009/sep/13/serena-williams-tirade-us-open

[10] Englert, C. (2016). The Strength Model of Self-Control in Sport and Exercise Psychology. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00314

[11] Fletcher, R. (2024). ITIA issues sanctions over tennis betting offences. iGB. igamingbusiness.com/sustainable-gambling/sports-integrity/itia-issues-sanctions-over-tennis-betting-offences/

[12] Fritsch, J., Jekauc, D., Elsborg, P., Latinjak, A., Reichert, M., & Hatzigeorgiadis, A. (2020). Self-talk and emotions in tennis players during competitive matches. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34(3), 518–538. doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2020.1821406

[13] Gucciardi, D. F., Jackson, B., Hanton, S., & Reid, M. (2015). Motivational correlates of mentally tough behaviours in tennis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18(1), 67–71. doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2013.11.009

[14] Harris, D. J., Vine, S. J., Eysenck, M. W., & Wilson, M. R. (2021). Psychological pressure and compounded errors during elite-level tennis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 56, 101987. doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101987

[15] Houwer, R., Kramer, T., den Hartigh, R., Kolman, N., Elferink-Gemser, M., & Huijgen, B. (2017). Mental Toughness in Talented Youth Tennis Players: A Comparison Between on-Court Observations and a Self-Reported Measure. Journal of Human Kinetics, 55, 139–148. doi.org/10.1515/hukin-2017-0013

[16] International Tennis Federation. (2023). CODE OF CONDUCT MEN’S AND WOMEN’S ITF WORLD TENNIS TOUR. www.itftennis.com/media/8955/world-tennis-tour-code-of-conduct.pdf

[17] Kavussanu, M., & Al-Yaaribi, A. (2019). Prosocial and antisocial behaviour in sport. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 19(2), 179–202. doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1674681

[18] Lake, R. J. (2015). The ‘Bad Boys’ of Tennis: Shifting Gender and Social Class Relations in the Era of Na˘stase, Connors, and McEnroe. Journal of Sport History, 42(2), 179–199. doi.org/10.5406/jsporthistory.42.2.0179

[19] Lev, A., Tenenbaum, G., Eldadi, O., Broitman, T., Friedland, J., Sharabany, M., & Galily, Y. (2022). “In your face”: The transition from physical to symbolic violence among NBA players. PLOS ONE, 17(5): e0266875. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266875

[20] Lewis, A. (2023). Doubles pair disqualified from French Open after ball hits ball girl. CNN. www.cnn.com/2023/06/04/tennis/miyu-kato-aldila-sutjiadi-french-open-default-spt-intl/index.html

[21] Livaudais, S. (2024). Does tennis need VAR? After Andrey Rublev’s controversial default in Dubai, players say it’s overdue. Tennis. www.tennis.com/baseline/articles/does-tennis-need-var-andrey-rublev-controversial-default-dubai-shouting-cursing-umpire-video-replay

[22] Maquirriain, J., & Baglione, R. (2016). Epidemiology of tennis injuries: An eight-year review of Davis Cup retirements. European Journal of Sport Science, 16(2), 266–270. doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2015.1009493

[23] Marazziti, D., Parra, E., Amadori, S., Arone, A., Palermo, S., Massa, L., Simoncini, M., Carbone, M. G., & Dell’Osso, L. (2021). Obsessive-Compulsive and Depressive Symptoms in Professional Tennis Players. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 18(6), 304–311. doi.org/10.36131/cnfioritieditore20210604

[24] Martin, W. (2022). 18-time Grand Slam winner Chris Evert says she’s worried about elite tennis players having ‘breakdowns’ after a spate of angry, aggressive behavior. Business Insider. www.businessinsider.com/chris-evert-fears-tennis-players-having-breakdowns-amid-angry-behavior-2022-4

[25] Moher, D., Hopewell, S., Schulz, K. F., Montori, V., Gøtzsche, P. C., Devereaux, P. J., Elbourne, D., Egger, M., & Altman, D. G. (2010). CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ, 340, c869. doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c869

[26] Monaci, M. G., & Veronesi, F. (2018). Getting Angry When Playing Tennis: Gender Differences and Impact on Performance. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 13(1). doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2017-0035

[27] Montalvan, B., Guillard, V., Ramos-Pascual, S., van Rooij, F., Saffarini, M., & Nogier, A. (2024). Epidemiology of Musculoskeletal Injuries in Tennis Players During the French Open Grand Slam Tournament From 2011 to 2022. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 12(4). doi.org/10.1177/23259671241241551

[28] NBA’s Psychiatry Program. (n.d.). The Family Center. www.thefamilycenter.tv/nba-psychiatry-program

[29] Okholm Kryger, K., Dor, F., Guillaume, M., Haida, A., Noirez, P., Montalvan, B., & Toussaint, J.-F. (2015). Medical Reasons Behind Player Departures From Male and Female Professional Tennis Competitions. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(1), 34–40. doi.org/10.1177/0363546514552996

[30] Palau, M., Baiget, E., Cortés, J., Martínez, J., Crespo, M., & Casals, M. (2024). Retirements of professional tennis players in second- and third-tier tournaments on the ATP and WTA tours. PLOS ONE, 19(6): e0304638. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304638

[31] Pineda-Hernández, S. (2022). Playing under pressure: EEG monitoring of activation in professional tennis players. Physiology & Behavior, 247, 113723. doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2022.113723

[32] Reuters. (2024). Rublev defaulted for screaming at line judge as Bublik reaches Dubai final. www.reuters.com/sports/tennis/rublev-defaulted-screaming-line-judge-bublik-reaches-dubai-final-2024-03-01/

[33] Rodríguez, D. S., & García, O. L. (2014). Psychological factors in tennis. Control of stress and its relation with physiological parameters. Movimiento humano, 6, 11–30.

[34] Stevenson, M., Sergeant, E., Heuer, C., Nunes, T., Heuer, C., Marshall, J., Sanchez, J., Thornton, R., Reiczigel, J., Robison-Cox, J., Sebastiani, P., Solymos, P., Yoshida, K., Jones, G., Pirikahu, S., Firestone, S., Kyle, R., Popp, J., Jay, M., … Rabiee, A. (2024). epiR: Tools for the Analysis of Epidemiological Data (Version 2.0.70) [Computer software]. cran.r-project.org/web/packages/epiR/index.html

[35] Subirana, I., Sanz, H., & Vila, J. (2014). Building Bivariate Tables: The compareGroups Package for R. Journal of Statistical Software, 57(12), 1–16. doi.org/10.18637/jss.v057.i12

[36] TADP rules. (2024). ITIA. www.itia.tennis/anti-doping/tadp/

[37] The Sydney Morning Herald. (2020, septiembre 7). Tennis players disqualified for on-court misconduct. The Sydney Morning Herald. www.smh.com.au/sport/tennis/novak-djokovic-defaulted-tennis-players-disqualified-for-on-court-misconduct-over-the-years-20200907-p55t07.html

[38] Tossici, G., Zurloni, V., & Nitri, A. (2024). Stress and sport performance: A PNEI multidisciplinary approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 15. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1358771

[39] University of Birmingham. (2022). Aggressive behaviour in sport and what we can do about it. University of Birmingham. www.birmingham.ac.uk/news/2022/aggressive-behaviour-in-sport

[40] Vandenbroucke, J. P., von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Mulrow, C. D., Pocock, S. J., Poole, C., Schlesselman, J. J., & Egger, M. (2014). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. International Journal of Surgery, 12(12), 1500–1524. doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.014

[41] Walker, I., Brierley, E., Patel, T., Jaffer, R., Rajpara, M., Heslop, C., & Patel, R. (2021). Mental health among elite sportspeople: Lessons for medical education. Medical Teacher, 44(2), 214–216. doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2021.1994134

[42] Weir, K. (2018). A growing demand for sport psychologists. 49(10). American Psychological Association 49(10), 50. www.apa.org/monitor/2018/11/cover-sports-psychologists

[43] Wickham, H. (2009). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer. doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-98141-3

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: April 3, 2025

Accepted: July 17, 2025

Published: January 1, 2026

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en