Meaningful Physical Education: Design and Validation of a Measurement Instrument

*Corresponding author: Pablo Saiz-González saizpablo@uniovi.es

Cite this article

Saiz-González, P. & Fernandez-Rio, J. (2025). Meaningful Physical Education: design and validation of a measurement instrument. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 161, 12-22. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2025/3).161.02

Abstract

Meaningful physical education is a novel approach that has roused significant interest in the English-speaking world in the physical education and sports pedagogy research field. However, all studies to date have used a qualitative research design based on interviews, focus groups, or drawings. The objective of this study was to design and validate a questionnaire-based instrument to study meaningful physical education (QSMPE) targeted at students in the last years of elementary school and all of high school. The objective of this tool was to evaluate learners’ perceptions of their experience in physical education classes from the meaningful physical education standpoint. The initial validation process included review by 5 experts in physical education and psychometric evaluation. A total of 1009 students from 5th to 11th grade agreed to participate. A total of 507 students (10-18 years; 255 male, 252 female) were recruited for the exploratory factor analysis, while information was collected from a separate sample of 502 students for the confirmatory factor analysis (10-16 years; 239 male, 263 female). We used the SPSS 25.0 statistics program for the exploratory factor analysis and the Mplus® statistics package for the confirmatory factor analysis. All the results showed that the developed instrument presents excellent psychometric validity. This includes 12 factors that coincide with the essential features of meaningful physical education: (1) Social interaction with classmates, (2) Social interaction with the teacher, (3) Fair challenge, (4) Personally relevant learning, (5) Fun, (6) Motor competence, (7) Novelty, (8) Attuning teaching style, (9) Participative teaching style, (10) Guiding teaching style, (11) Clarifying teaching style, and (12) Relief. In the immediate future, the QSMPE broadens research possibilities regarding this novel approach by enabling quantitative or mixed study designs. It will also serve as a useful tool that physical education teachers can use to evaluate and innovate in terms of their teaching strategies.

Introduction

Almost a decade ago, Beni et al. (2017) published the first article mentioning the term “Meaningful Physical Education.” Since then, it has appeared in a multitude of documents discussing the application of this concept in early childhood education (Smith et al., 2023), elementary school education (Cardiff et al., 2024), high school education (Howley et al., 2020), university education (Lynch & Sargent, 2020) and even in sports (Ní Chróinín et al., 2023). One could therefore say that “meaningful” physical education research and study has become a trending topic in the English literature; however, in Spanish literature it has only been mentioned twice (Fernandez-Rio & Saiz-González, 2023; Saiz-González et al., 2025).

Essentially, Beni et al. (2017) were interested in discovering the characteristics of physical education experiences that students consider to be meaningful. With that in mind, they used Kretchmar’s definition (2007) of “meaningful” experiences: those that an individual interprets and attributes value by assigning them personal significance. Along the same line, Chen (1998) proposed that meaningful physical education experiences are influenced by the value the learner attributes to them and the learning goals identified by the learner, highlighting the value of student perception rather than teacher perception. The experiences of each learner have individual, personal meaning and are impacted by emotional and sociocultural aspects (Light et al., 2013).

On the other hand, the emergence of pedagogical models in the last two decades of the 20th century in the English-speaking world, and almost 20 years later in Spain (Fernandez-Rio et al., 2016), represented a significant methodological shift, as they proposed adopting student-centered teaching. Nevertheless, research has shown that if pedagogical models are not properly implemented, they may not produce the intended benefits of said pedagogical approaches (Fernandez-Rio & Iglesias, 2024). Meaningful physical education represents the appearance of a new paradigm in physical education and sports pedagogy, wherein what truly matters are the perceptions of those on the receiving end of the pedagogical approaches used: the students. However, this approach not only impacts the learner’s perception, it also boosts the learning processes and contributes to developing competences, thus fostering relevant learning experiences (Beni et al., 2017; Fletcher et al., 2021).

In that vein, the aforementioned revision by Beni et al. (2017) aimed to identify which features promote meaningful experiences in different physical education and sports settings. To do so, they used the features Kretchmar (2006) had previously defined: social interaction, fun, challenge, increased motor competence, and enjoyment. Kretchmar thought these features could help guide physical education teachers design and teach their classes, ensuring they represented meaningful experiences for their students. Experiences that are satisfying, challenging, social, or fun and that help promote an active lifestyle among young people (Teixeira et al., 2012).

Therefore, based on the features initially selected by Kretchmar (2006), Beni et al. (2017) identified six essential features to consider in any approach that aims to develop meaningful physical education. Fletcher et al. provided in-depth definitions of these features (2021): (1) Social interaction: understood as relationships that occur in class both between students and between the teacher and students, a concept backed by self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2020), which describes the need for positive relationships as the foundation for intrinsic motivation; (2) Fun: very important for repeating an activity, and for this, success must be redefined to ensure it is self-referenced and learning-oriented, in line with the Student Self-Oriented Learning Model (Fomichov & Fomichova, 2019) which states that personal experience is beneficial for self-cognition and self-construction; (3) Fair challenge: the challenge behind class activities must be appropriate to each student, motivating them to try to participate, and to try new skills, which is connected to the Learning Zones Model (Senninger, 2000) in that it suggests that individuals learn when they are challenged; (4) Motor competence: the student feels their motor skills are effective in class, a concept that is again included in the scope of self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2020), which states that an individual must feel competent in order to reach the highest levels of motivation; (5) Personally relevant learning: the learning that occurs is unequivocally important to each individual, focusing on transparency and class transfer in the framework of a democratic pedagogy, which is connected to Dewey’s (1938) ideas about giving students a voice and a vote in the classroom; and (6) Enjoyment: represents a step beyond mere fun, as it involves the student integrating the stimulus (physical education class) as an intrinsic motivator, once again in line with self-determination theory (Fernandez-Rio & Saiz-González, 2023). Recently, Saiz-González et al. (2025) reviewed the adequacy (or lack thereof) of these features within the Spanish-speaking context, and added three new features: (7) Novelty: necessary for keeping learners interested in physical education classes. It has been widely studied and set forth as a new basic psychological need (González-Cutre et al., 2016); (8) Interpersonal teaching style: how classes are presented defines the type of educational setting created, in line with the circumflex approach proposed by Aelterman et al. (2019), which describes how different interpersonal teaching styles are related and determine the motivational environment in the classroom; and (9) Relief: as a counter to other “passive” educational activities, “active” tasks are required to recharge “energy,” with the understanding that, in line with Priniski et al. (2018), this idea of physical education being a ‘relief’ arises from attributing value to the class as a form of active learning and not a simple pause in the day.

On the other hand, when teachers do not pay attention to the meaning that physical education classes have for their students, the learners do not perceive it as important or valuable (Lodewyk & Pybus, 2012), resulting in negative consequences in terms of an active and healthy lifestyle. A recent study showed that only those students who considered physical education class to be important to their lives (in other words, it was meaningful to them) chose the class when it was an elective course in their last year of high school (Fernandez-Rio et al., 2023).

To date, all research into meaningful physical education has used qualitative methods (interviews, focus groups, drawings, open-ended questions…; e.g., Beni et al., 2023; Coulter et al., 2023; Ní Chróinín et al., 2023, Scanlon et al., 2024) since, to our knowledge, there are no tools for conducting quantitative research under the conceptual framework of meaningful physical education. Considering the recent increase in studies involving this approach due to rising interest, and the lack of quantitative studies, it would be important to create research instruments that enable this kind of data to be extracted for future studies. To our knowledge, no instruments have been published in either Spanish or English, designed within the conceptual framework of meaningful physical education. Therefore, its creation positions Spanish physical education and sports pedagogy research at the global forefront, as it is the first of its kind to specifically broach this perspective, offering a tool for both researchers and physical education and sports educators.

As mentioned above, the primary objective of this study was to design and validate a questionnaire to assess the perceptions of students in the later years of elementary school and all high school years regarding their experience in physical education classes with a focus on meaningful physical education.

Methodology

Procedure

Before starting the research, we obtained permission from the University of Oviedo Ethics Committee (23-RRI-2024). We reached out to elementary and high school teachers from various Spanish regions, asking them to collaborate. For those who accepted, we explained the project to them as well as the procedure for recruiting participants and collecting data. Teachers interested in participating then contacted their students’ parents or legal guardians to explain the project. Families who expressed interest in having their children participate signed an informed consent form that detailed the voluntary nature of participation and the freedom to abandon the study at any time. The digital questionnaire was completed during the students’ class hours in a regular classroom to help ensure a calm atmosphere. After analyzing the questionnaire in a pilot study conducted to assess the content validity and applicability of the scale, it was estimated that the questionnaire took around 20-25 minutes to complete. Data collection for the exploratory factor analysis started in April 2024 and ended in June 2024. For the confirmatory factor analysis, data collection started in September and ended in October 2024.

Questionnaire for the Study of Meaningful Physical Education (QSMPE)

Two university professors with extensive experience in research in the field created all the initial instrument items (Muñiz et al., 2005). The teachers had between 3 and 30 years of physical education teaching and research experience and also had prior experience in the creation and validation of questionnaires and the study of meaningful physical education. Initially, the prior study that defined the basic features for this model within the Spanish context was used as the basis (Saiz-González et al., 2025): (1) Social interaction, (2) Fun, (3) Fair challenge, (4) Motor competence, (5) Personally relevant learning, (6) Novelty, (7) Teacher interpersonal style (8) Relief.

These eight initial features then underwent some changes. First, based on the work by Fernandez-Rio and Saiz-González (2023) and Saiz-González et al. (2025), the feature (1) Social interaction was divided in two to clearly identify the source of these positive connections that occurred in the physical education classroom: (1) with classmates and (2) with the teacher. Second, based on the work of Aelterman et al. (2019) and Van Doren et al. (2023), we decided to divide the feature (8) Teaching style, into four positive styles according to the above studies, which could be conducive to meaningful physical education experiences for the students: (8) Attuning, (9) Participative, (10) Guiding, and (11) Clarifying (two were left out due to their connection to a chaotic teaching style as they were considered negative for students: abandonment and waiting). Thus, the following 12 features made up the set of “initial factors” proposed for the Questionnaire for the Study of Meaningful Physical Education (QSMPE): (1) Social interaction with classmates, (2) Social interaction with the teacher, (3) Fair challenge, (4) Personally relevant learning, (5) Fun, (6) Motor competence, (7) Novelty, (8) Attuning teaching style, (9) Participative teaching style, (10) Guiding teaching style, (11) Clarifying teaching style, and (12) Relief.

Each teacher involved in the initial design drafted 6 items for each of the 12 independent features. They then discussed and debated the items and as a team selected the final set of items for each of the possible factors (features). During this process they decided to use a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = Strongly disagree to 6 = Strongly agree for questions starting with: “In physical education class…”

Content validity and applicability

A panel of five expert professors from three different Spanish universities evaluated the content validity and applicability of the first version of the instrument. They checked the content validity for each of the items to prevent any duplication/similarity and evaluated the clarity of the writing and relevance of the items. As a result, the panel of experts proposed including, modifying, or removing some of the items. As such, the creation process was based on prior theoretical knowledge of meaningful physical education (Fletcher et al., 2021; Saiz-González et al., 2025; Aelterman et al., 2019; Van Doren et al., 2023), as described in the previous section. To facilitate their evaluation, the experts received a table with the items classified by the theoretical dimensions in addition to the clarity, relevance, and adequacy criteria. A pilot study was then conducted with 12 students with similar ages to those of the target sample to assess whether the selected items were easy to understand, had any grammar errors, and how long it would take to complete the questionnaire. An introductory sentence was added: “The goal of this questionnaire is to learn about your perception of physical education classes. There are no correct or incorrect answers, we just want to know your opinion.”

Psychometric validity evaluation and factorial reliability

After the panel of experts analyzed the content validity and following the pilot study, the final scale comprised of 48 items (four for each of the 12 dimensions) was statistically evaluated. An exploratory factor analysis of the instrument was conducted using 507 responses and a confirmatory factor analysis using another 502 responses.

Data Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis

507 students from 5th grade and up agreed to participate (mean age = 14.43; SD = 1.75; range = 10-18 years; 255 male, 252 female). Specifically, 423 students were in middle school or high school (last six years of education). 132 were in 7th grade, 56 in 8th grade, 87 in 9th grade, 52 in 10th grade, and 96 in 1st year of Baccalaureate (equivalent to 11th grade). As for elementary and middle school, 51 were in 5th grade and 33 in 6th grade.

We used the SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Statistics, v.25.0, Chicago, IL, USA) statistics program for the exploratory factor analysis, taking into account the principle components and the varimax orthogonal rotation to examine the factorial structure of the scale. The adequacy of the factor analysis was evaluated by calculating the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The consistency of the items, or the internal reliability, was analyzed using Cronbach’s alpha and the Omega coefficient (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

Confirmatory factor analysis

502 students starting from 5th grade and up (not the same students as those used for the exploratory factor analysis) agreed to participate (mean age = 12.86; SD = 1.13; range = 10-16 years; 239 male, 263 female). Specifically, 318 students were in middle school or high school (last six years of education). 115 were in 7th grade, 131 in 8th grade, 21 in 9th grade, and 51 in 10th grade. As for elementary and middle school, 62 were in 5th grade and 122 in 6th grade.

We used the Mplus® (version 8; Statmodel®) statistics package to conduct the confirmatory factor analysis via the maximum similarity parameters estimation method. The following indices were used for this analysis: chi-squared (χ²); CFI: comparative fit index (recommended value > .90); RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation (values < .08 suggest a reasonable fit between the model and data); SRMR: standardized root mean squared residual (recommended value < .08); TLI: Tucker-Lewis Index (recommended values > .90); CR: composite reliability (recommended value > .70); and AVE: average variance extracted (recommended value > .50). Lastly, a bivariate correlation analysis was performed between the scale factors to analyze their discriminant validity, following the example set by similar studies in the field (e.g., Leo et al., 2023). These indices make it possible to evaluate the goodness of fit of the proposed model compared to the observed data, where values within the recommended ranges indicate a satisfactory fit (Kline, 2023).

Results

Content validity and applicability

The level of agreement among the five experts who evaluated the 72 initial items was analyzed using Fleiss’ Kappa coefficient (Fleiss, 1981), obtaining excellent agreement (κ = .79). Based on the experts’ opinions, we eliminated the two worst items for each feature, reducing the questionnaire to 48 items. For example, some of the eliminated items were “The games help us get to know each other better as classmates (Social interaction with classmates),” “I feel like we are all given the chance to progress at our own pace (Fair

(Fair challenge),” “The teacher tries to make class more enjoyable for us” (Attuning teaching style) or “I disconnect from regular classroom activities (Relief).” The same process was then repeated with a group of students, (N = 12), and also obtained an excellent level of agreement (κ = .91). Based on their feedback, we revised three items as follows: “The tasks and games are entertaining and motivating” was changed to “I think the tasks/activities and games are entertaining,” “I feel free to express my ideas” was replaced with “I feel comfortable expressing my opinions in front of my classmates,” and “I think I am skillful” was reformulated into “I think I have the skills to successfully participate in the tasks/activities and games.” The approximate time to complete the questionnaire was 20-25 minutes.

Psychometric validity evaluation and factorial reliability

The KMO index presented an adequacy value of .96 (Kaiser, 1974). Bartlett’s test of sphericity was also significant (p < .001), confirming the adequacy of the data. As seen in Table 1, own values higher than .95 were obtained for all the factors and a total explained variation of 77.43%. The factorial correlations were low-moderate in all cases.

The exploratory factor analysis provided a result made up of 12 factors, each with four items: (1) Social interaction with classmates, (2) Social interaction with the teacher, (3) Fair challenge, (4) Personally relevant learning, (5) Fun, (6) Motor competence, (7) Novelty, (8) Attuning teaching style, (9) Participative teaching style, (10) Guiding teaching style, (11) Clarifying teaching style and (12) Relief. Table 2 shows this factorial structure.

Lastly, all the factors presented acceptable internal consistency scores: (1) Social interaction with classmates (α = .87; ω = .87), (2) Social interaction with the teacher (α = .91; ω = .91), (3) Fair challenge (α = .91; ω = .91), (4) Personally relevant learning (α = .92; ω = .92), (5) Fun (α = .91; ω = .92), (6) Motor competence (α = .89; ω = .89), (7) Novelty (α = .86; ω = .87), (8) Attuning teaching style (α = .86; ω = .86), (9) Participative teaching style (α = .87; ω = .87), (10) Guiding teaching style (α = .90; ω = .90), (11) Clarifying teaching style (α = .92; ω = .92) and (12) Relief (α = .91; ω = .91; Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994).

Confirmatory factor analysis

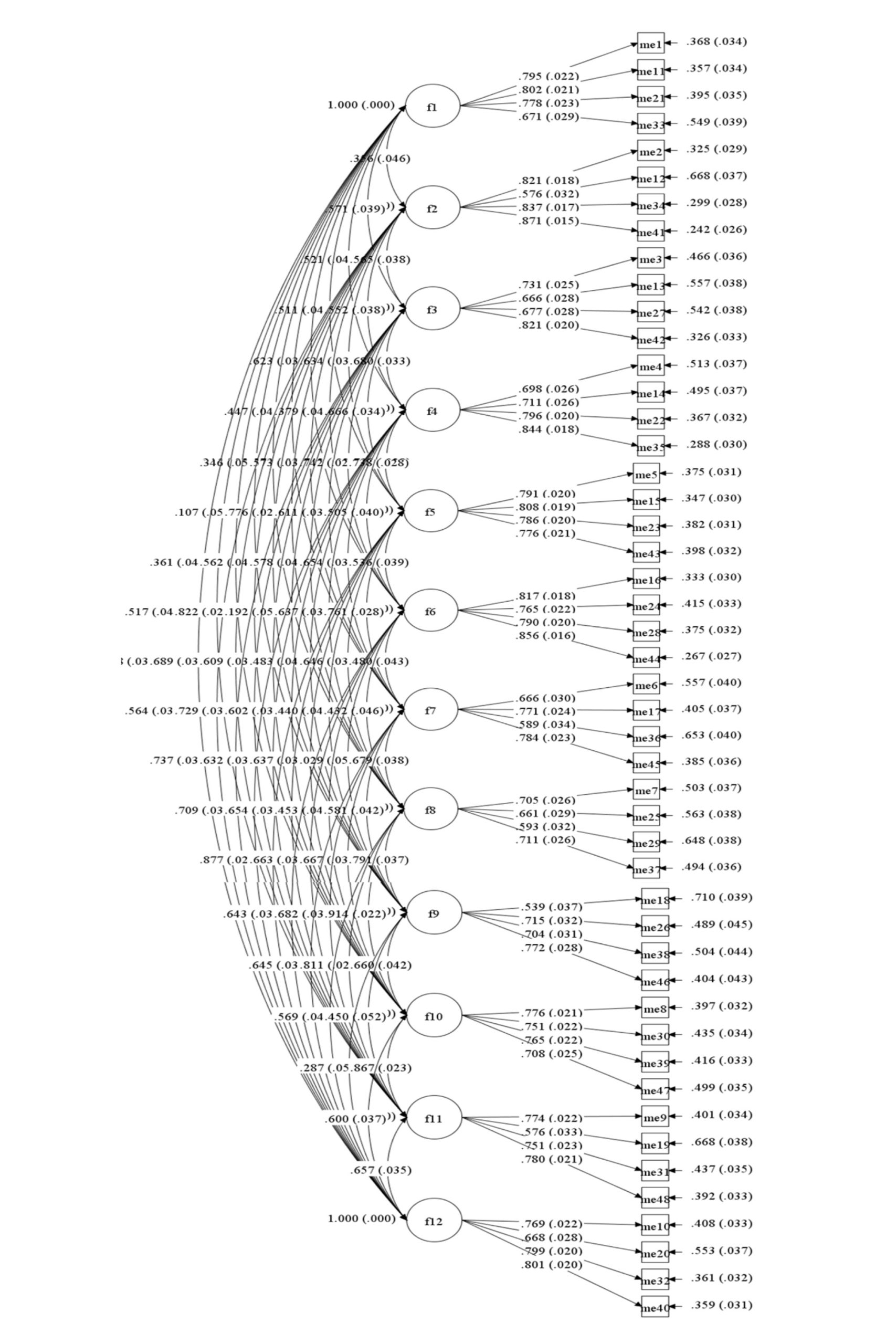

The confirmatory factor analysis was conducted with the second sample participant responses to determine the factorial structure obtained in the exploratory factor analysis. To do so, the maximum likelihood estimation was used with robust estimators. The results confirmed the factorial structure discovered in the exploratory factor analysis: χ2 = 2327, p = < .001, SRMR = .053, RMSEA = .05 (95% CI: .04, .05), CFI = .91 and TLI = .90. The standardized factorial loads for each of the items were analyzed in their respective factors according to the hypothesized theoretical model (Figure 1). In summary, all the items presented adequate values for each of the factors: (a) F1 (λ = .67-.80); (b) F2 (λ = .58-.87); (c) F3 (λ = .67-.82); (d) F4 (λ = .70-.84); (e) F5 (λ = .78-.81); (f) F6 (λ = .77-.86); (g) F7 (λ = .59-.78); (h) F8 (λ = .59-.78); (i) F9 (λ = .54-.77); (j) F10 (λ = .71-.78); (k) F11 (λ = .58-.78); and (l) F12 (λ = .67-.80). Thus, the twelve-factor structure defined by the exploratory factor analysis was confirmed.

Lastly, descriptive analysis, internal consistency (α, ω and CR), convergent validity (AVE) and discriminant validity analyses were conducted (bivariate correlations) (Table 3). The values were acceptable for all the factors with the exception of two (Attuning teaching style and Participative teaching style), which presented values slightly below the recommended threshold. However, due to their high internal consistency values (CR > .70) and theoretical relevance, we decided to keep them.

Table 3

Descriptive Analysis, Internal Consistency (α, ω and CR), Convergent Validity (AVE), and Discriminant Validity

Discussion

The study objective was to design and validate a questionnaire to evaluate learners’ perceptions of their experience in physical education classes from the meaningful physical education standpoint. The validation process included an expert evaluation of the content validity and a pilot study with representative participants from the target population, as well as exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. The results showed theQSMPE instrument has excellent psychometric validity. This includes 12 factors that coincide with the essential features of meaningful physical education: (1) Social interaction with classmates, (2) Social interaction with the teacher, (3) Fair challenge, (4) Personally relevant learning, (5) Fun, (6) Motor competence, (7) Novelty, (8) Attuning teaching style, (9) Participative teaching style, (10) Guiding teaching style, (11) Clarifying teaching style and (12) Relief.

The content validity and applicability allowed us to determine that the QSMPE tool measures what it is intended to measure, and can be used with students from 5th through 11th grade. Both the exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (conducted with different samples of over 500 participants) confirmed that the data collection instrument has excellent psychometric properties (factor reliability and validity).

Beyond the good psychometric data obtained, validation of the QSMPE represents an important step forward in a line of research that is likely to be prioritized in the near future in physical education. As stated in the introduction, in physical education and sports pedagogy in the English-speaking world, the intensity of meaningful physical education research has grown exponentially in the last five years, resulting in a constant trickle of new scientific research publications (Beni et al., 2021, 2023; Coulter et al., 2023; Ní Chróinín et al., 2023; Scanlon et al., 2024, etc.). Some researchers have started studying its connections with other currently trending lines of research such as social justice (Ní Chróinín et al., 2024), posing that the principles of the former (e.g., social interaction, personally relevant learning) can help develop the latter with regards to early teacher training in universities. An initial article has already been published in Spain presenting this approach (Fernandez-Rio & Saiz-González, 2023), with notable impact as measured by mentions on social media (tweets, infographs, podcasts…) and invitations to teach courses at multiple universities around the country to help share their knowledge. This suggests that this approach is “here to stay” and will be intensively used and studied. Therefore, it is likely that information collection instruments, such as that validated in this study, will shortly be needed.

As described, meaningful physical education goes one step further in student-centered teaching by placing students in the “center of the picture and empowering them,” aiming to provide them with physical education experiences that positively impact their lives (Ní Chróinín et al., 2018). This shift in perspective allows teachers to develop learning experiences that hold meaning for each of their students according to their interests, needs, and priorities (Vasily et al., 2021). Therefore, the proposed physical education is one that is democratic, in which students’ voices are heard and they can make decisions (choose), and that is reflexive, in which what has been done in class and what will be done is discussed (debate) (Beni et al., 2019).

In the same way that the arrival of pedagogical models in Spain represented a shift in the approach to physical education learning and teaching (Fernandez-Rio et al., 2016; Pérez-Pueyo et al., 2021), the emergence of meaningful physical education must also entail a paradigm shift. This involves discovering the impact of teaching approaches on the true protagonist: the student. While it took close to 40 years for pedagogical models to gain popularity in Spain, the validated study instrument, the QSMPE, may significantly help this approach to be implemented and studied in a fairly immediate manner, as is currently happening in the English-speaking physical education and sports pedagogy world (Fletcher et al., 2021; Fletcher & Ní Chróinín, 2022; Ní Chróinín et al., 2018). The questionnaire presented in this article will position the study of physical education in the Spanish-speaking world on the same level as, or even more advanced than, the English-speaking world.

Though the QSMPE has been proven to have excellent psychometric properties, it could be interesting to evaluate its stability over time via a longitudinal analysis, test-retest, to assess the consistency of the score over the course of time. One study limitation is the impossibility of reapplying the questionnaire to the same sample used in this study, and it is recommended that this be addressed in future research.

Conclusion

The instrument developed in this study will broaden research opportunities in meaningful physical education by enabling the design of quantitative or mixed studies. It represents a very important step forward in implementing and studying this new pedagogical approach that aims to understand how students themselves perceive their physical education experiences. The QSMPE gives those students a voice, helping to better understand their needs and adapting classes to provide real meaning in their lives. In addition to the research context, teachers can also use this questionnaire to collect information about their own classes. That information will help improve their teaching quality, adapting content and methodologies to the students’ interests, motivations, and needs. Thus, from the students’ perspective, this instrument may serve as a point of dialogue for communicating with their teachers (anonymously or not) about their experiences in this class. The presented instrument may provide information that helps both physical education research and teaching to continue progressing.

References

[1] Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Haerens, L., Soenens, B., Fontaine, J. R., & Reeve, J. (2019). Toward an integrative and fine-grained insight in motivating and demotivating teaching styles: The merits of a circumplex approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(3), 497. dx.doi.org/10.1037/edu0000293

[2] Beni, S., Fletcher, T., & Ní Chróinín, D. (2017). Meaningful Experiences in Physical Education and Youth Sport: A Review of the Literature, Quest, 69(3), 291-312. doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1224192

[3] Beni, S., Ní Chróinín, D., & Fletcher, T. (2019). A focus on the ‘how’ of meaningful physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 24, 624-637. doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1612349

[4] Beni, S., Ní Chróinín, D., & Fletcher, T. (2021). ‘It’s how PE should be!’: Classroom teachers’ experiences of implementing Meaningful Physical Education. European Physical Education Review, 27(3), 666-683. doi.org/10.1177/1356336X20984188

[5] Beni, S., Ní Chróinín, D., Fletcher, T., Bailey, J., Cariño, L., Down, M., Hamada, M., Riddick, T., Trojanovic, M., & Gross, K. (2023). Teachers’ sensemaking in implementation of Meaningful. Physical Education, Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 1-14. doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2023.2260388

[6] Cardiff, G., Beni, S., Fletcher, T., Bowles, R., & Chróinín, D. N. (2024). Learning to facilitate student voice in primary physical education. European Physical Education Review, 30(3), 381-396. doi.org/10.1177/1356336X231209687

[7] Chen, A. (1998). Meaningfulness in physical education: A description of high school students’ conceptions. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 17, 285–306. doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.17.3.285

[8] Coulter, M., Gleddie, D., Bowles, R., NiChroinin, D., & Fletcher, T. (2023). Teacher Educators’ Explorations of Pedagogies that Promote Meaningful Experiences in Physical Education. Revue phénEPS/PHEnex Journal, 13(3).

[9] Dewey, J. (1938). Experience And Education. Kappa Delta Phi.

[10] Fernández-Río, J., Calderón, A., Hortigüela, D., Pérez-Pueyo, Á., & Aznar, M. (2016). Modelos pedagógicos en educación física: consideraciones teórico-prácticas para docentes. Revista Española de Educación Física y Deportes, 413, 55-75. doi.org/10.55166/reefd.v0i413.425

[11] Fenandez-Rio, J., García, S., & Ferriz-Valero, A. (2023). Selecting (or not) physical education as an elective subject: Spanish high school students’ views. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 1–13. doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2023.2256762

[12] Fernandez-Rio, J., & Iglesias, D. (2024). What do we know about pedagogical models in physical education so far? An umbrella review. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 29(2), 190-205. doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2022.2039615

[13] Fernandez-Rio, J., & Saiz-González, P. (2023). Educación Física con Significado (EFcS). Un planteamiento de futuro para todo el alumnado. Revista Española de Educación Física y Deportes, 437(4), 1-9. doi.org/10.55166/reefd.v437i4.1129

[14] Fomichov, V. A., & Fomichova, O. S. (2019). The student-self oriented learning model as an effective paradigm for education in knowledge society. Informatica, 43(2019), 95–107. doi.org/10.31449/inf.v43i1.2356

[15] Fleiss, J. L. (1981). Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions (2nd edition). Wiley-Interscience.

[16] Fletcher, T., & Ní Chróinín, D. (2022). Pedagogical principles that support the prioritisation of meaningful experiences in physical education: conceptual and practical considerations. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 27(5), 455-466. doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1884672

[17] Fletcher, T., Ní Chróinín, D., Gleddie, D., & Beni, S. (Eds.). (2021). Meaningful Physical Education: An Approach for Teaching and Learning (1st ed.). Routledge. doi.org/10.4324/9781003035091

[18] González-Cutre, D., Sicilia, Á., Sierra, A. C., Ferriz, R., & Hagger, M. S. (2016). Understanding the need for novelty from the perspective of self-determination theory. Personality and individual differences, 102, 159-169. doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.036

[19] Howley, D., Dyson, B., Baek, S., Fowler, J., & Shen, Y. (2022). Opening up Neat New Things: Exploring Understandings and Experiences of Social and Emotional Learning and Meaningful Physical Education Utilizing Democratic and Reflective Pedagogies. International Journal of Environmental Research in Public Health, 19, 11229. doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811229

[20] Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39(1), 31–36. doi.org/10.1007/BF02291575

[21] Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (5th edition). Guilford Publications.

[22] Kretchmar, R. S. (2006). Ten more reasons for quality physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 77(9), 6–9. doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2006.10597932

[23] Kretchmar, R. S. (2007). What to do with meaning? A research conundrum for the 21st century. Quest, 59, 373–383. doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2007.10483559

[24] Leo, F. M., Fernández-Río, J., Pulido, J. J., Rodríguez-González, P., & López-Gajardo, M. A. (2023). Assessing class cohesion in primary and secondary education: Development and preliminary validation of the class cohesion questionnaire (CCQ). Social Psychology of Education, 26(1), 141–160. doi.org/10.1007/s11218-022-09738-y

[25] Light, R. L., Harvey, S., & Memmert, D. (2013). Why children join and stay in sports clubs: Case studies in Australian, French and German swimming clubs. Sport, Education and Society, 18(4), 550-566. doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2011.594431

[26] Lodewyk, K. R., & Pybus, C. M. (2012). Investigating factors in the retention of students in high school physical education. Journal of teaching in physical education, 32(1), 61-77. doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.32.1.61

[27] Lynch, S., & Sargent, J. (2020). Using the meaningful physical education features as a lens to view student experiences of democratic pedagogy in higher education, Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 25(6), 629-642.

[28] Muñiz, J., Fidalgo, A. M., García-Cueto, E., Martínez, R., & Moreno, R. (2005). Análisis de los ítems: 30. Arco Libros - La Muralla, S.L.

[29] Ní Chróinín, D., & Fletcher, T. (2023). Teaching and Coaching for Meaningfulness and Joy. En V. Girginov, & R. Marttinen (Eds.). Routledge. doi.org/10.4324/9780367766924-RESS58-1

[30] Ní Chróinín, D., Fletcher, T., Beni, S., Griffin, C., & Coulter. M. (2023) Children’s experiences of pedagogies that prioritise meaningfulness in primary physical education in Ireland. Education 3-13, 51(1), 41-54 doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2021.1948584

[31] Ní Chróinín, D., Fletcher, T., & Griffin, C. (2018). Exploring pedagogies to promote meaningful participation in primary PE. Physical Education Matters, 13(2), 70-73. doi.org/10.1177/1356336X18755050

[32] Ní Chróinín, D., Fletcher, T., & O’Sullivan, M. (2018). Pedagogical principles of learning to teach meaningful physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(2), 117-133. doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2017.1342789

[33] Ní Chróinín, D., Iannucci, C., Luguetti, C., & Hamblin, D. (2024). Exploring teacher educator pedagogical decision-making about a combined pedagogy of social justice and meaningful physical education. European Physical Education Review. doi.org/10.1177/1356336X24124040

[34] Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric Theory (3rd edition). McGraw-Hill.

[35] Pérez-Pueyo, Á., Hortigüela-Alcalá, D., & Fernández-Río, J. (2021). Los modelos pedagógicos en educación física: qué, cómo, por qué y para qué. Universidad de León.

[36] Priniski, S.J., Hecht, C.A., & Harackiewicz, J.M. (2018). Making learning personally meaningful: A new framework for relevance research. The Journal of Experimental Education, 86(1), 11–29. doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2017.1380589

[37] Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary educational psychology, 61, 101860. doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

[38] Saiz-González, P., Sierra-Díaz, J., Iglesias, D., & Fernandez-Rio, J. (2025). Chasing Meaningfulness in Spanish Physical Education: Old and New Features. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 1-9. doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2024-0206

[39] Scanlon, D., Becky, A., Wintle, J., & Hordvik, M. (2024). ‘Weak’physical education teacher education practice: co-constructing features of meaningful physical education with pre-service teachers. Sport, Education and Society, 1-16. doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2024.2344012

[40] Senninger, T. (2000). Abenteuer leiten-in Abenteuern lernen: Methodenset zur Planung und Leitung kooperativer Lerngemeinschaften für Training und Teamentwicklung in Schule, Jugendarbeit und Betrieb. Ökotopia Verlag.

[41] Smith, Z., Carter, A., Fletcher, T., & Chróinín, D. N. (2023). What is important? How one early childhood teacher prioritised meaningful experiences for children in physical education. Journal of Early Childhood Education Research, 12(1), 126-149.

[42] Teixeira, P. J., Carraça, E. V., Markland, D., Silva, M. N., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9, 78. doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-78

[43] Van Doren, N., De Cocker, K., Flamant, N., Compernolle, S., Vanderlinde, R., & Haerens, L. (2023). Observing physical education teachers’ need-supportive and need-thwarting styles using a circumplex approach: how does it relate to student outcomes? Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 1-25. doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2023.2230256

[44] Vasily, A., Fletcher, T., Gleddie, D., & Chroinín, D. N. (2021). An actor-oriented perspective on implementing a pedagogical innovation in a cycling unit. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 40(4), 652-661. doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2020-0186

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: December 19, 2024

Accepted: March 19, 2025

Published: July 1, 2025

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en