Enhancing Physical Activity in the Classroom with Active Breaks: A Mixed Methods Study

*Corresponding author: Oleguer Camerino ocamerino@inefc.es

Cite this article

Jiménez-Parra, J.F., Manzano-Sánchez, D., Camerino, O., Castañer, M. & Valero-Valenzuela, A. (2022). Enhancing Physical Activity in the Classroom with Active Breaks: A Mixed Methods Study. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 147, 84-94. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2022/1).147.09

Abstract

Educators who integrate physical activity (PA) into the classroom stimulate their students and create an engaging environment. The objective of this study was to verify the result of an active methodology programme based on activity breaks to demonstrate: a) the effect of the strategies proposed by the teacher, b) the characteristics of the physical exercises proposed and c) the responses produced in the students during the period of physical activity. A tutor-teacher (6th year of Primary Education) from an educational centre in the Murcia region and a total of 26 students between 11 and 13 years old (M = 11.95; SD = 0.63) took part. The programme was administered for 12 weeks using various procedures during school hours (12 sessions/week). The mixed methods approach allowed combining the quantitative analysis of the implementation of the active break, with an assessment check list and qualitative analysis of the result of the interactive behaviours that appeared, using systematic observational methodology (OM). The results showed that the active break involved the students intensively through a combination of motor skills, postural variations and varied interrelationships. At the same time, it was found that the teacher applied the strategies to promote physical activity more frequently in the classroom when they were: an interruption of the class, movement as social interaction, a proposal with a concrete structure, active participation and cooling down. It was concluded that the activity break programme may be suitable to increase motor participation, as well as the social and cognitive interaction of students during class.

Introduction

Childhood obesity has grown exponentially in recent years, which has led to a state of alert in the educational systems of various countries. In this regard, a sedentary lifestyle has become a key factor in the development of childhood obesity (Blanco et al., 2020), putting the health of young people at risk due to its links with negative consequences such as hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and bone diseases (Orsi et al., 2011). Faced with this situation, the World Health Organization (WHO, 2016), in its report “Ending childhood obesity”, focuses attention on schools, the family environment and other socialising and educational environments as being responsible for guiding children and adolescents towards the establishment of a healthy diet and the regular practice of physical activity that lets young people acquire healthy lifestyle habits. In addition, the recommendations established by the WHO (2016) indicate that the age group from 5 to 17 years old should do a minimum of 60 minutes of physical activity every day at a moderate/vigorous intensity and reduce the time they spend using screens.

Thus, numerous investigations suggest the promotion of interventions in schools to combat childhood obesity (Sánchez-López et al., 2019). Healthy habits promoted by physical activities in the classroom can contribute to: a) reducing the risk of diseases (Timmons et al., 2012), b) improving emotional health (Poitras et al., 2016) and c) enhancing learning motivation (Chacón-Cuberos et al., 2020). Along these lines, various empirical studies have analysed the effect of applying various strategies in educational centres to increase physical activity during school hours and to reduce the time students spend seated, such as physical activity programs (Ordóñez et al., 2019), active transport (Sanz Arazuri et al., 2017), active recreation (Méndez-Giménez and Pallasá-Manteca, 2018) and active breaks (Muñoz-Parreño et al., 2020).

Due to the mandatory nature of the current Spanish educational system and the persistence of traditional methodologies in primary and secondary education, it is reasonable to think that children and adolescents dedicate a large part of their time to static learning. However, schools could play a fundamental role in promoting physical activity (Langford et al., 2015; Méndez-Giménez and Pallasá-Manteca, 2018), not only through the subject of Physical Education, but also through the use of other interdisciplinary physical and sports activities that allow their positive effects to affect the entire school population (Ordóñez et al., 2019). Along these lines, the study by Hernández et al. (2010) showed that the physical involvement of students during the school day is very low, their inactivity even exceeded 90% of their time, with most time spent in sedentary school activity. Faced with this situation, various authors (Dyrstad et al., 2018) request organisational changes in educational centres that favour the incorporation of physical activity into the school day, due to the numerous cognitive, academic, and physical-health and behavioural benefits it provides to young people (Masini et al., 2020). It seems that the primary education period is a key one for developing active behaviour patterns in children (Castañer et al., 2011) and for promoting the acquisition of healthy lifestyle habits that contribute to reducing overweight and obesity, factors that are closely related to the maintenance of sporting habits when older (Ordóñez et al., 2019; Vaquero-Solís et al., 2020).

One of the most used strategies in recent years to reduce children and adolescent’s sedentary lifestyle are classroom-based physical activity (Watson et al., 2017a), which can be carried out both inside and outside the classroom. Watson et al. (2017a; 2017b) distinguish three ways to incorporate physical activity into the classroom: a) active breaks, defined as short periods of time, between 5 and 15 minutes, in which physical activity is incorporated at a moderate to vigorous intensity, during a class, without the need for special spaces, material or personnel (Masini et al., 2020); b) Curriculum-focused active breaks, short periods of physical activity that include curricular content (Schmidt et al., 2016), and c) Physically active lessons, in which physical activity is integrated into education other than physical education (Riley et al., 2015).

Scientific evidence shows the benefits of incorporating active breaks in the classroom to increase levels of physical activity in students, both during the school day and after school (Muñoz-Parreño et al., 2020), which can reach 50% of the recommendations established by the WHO (Fairclough et al., 2012) and higher levels of physical fitness (Ridgers et al., 2007). Its positive effects are also seen in other variables such as attention span, concentration, executive functions and behaviour towards the task (De Greeff et al., 2018; Masini et al., 2020; Méndez–Giménez, 2020; Watson et al., 2017b).

However, despite the fact that, in recent years, the importance of observation in the educational field has become greater for PE (Valero-Valenzuela et al., 2020) as well as for the rest of the subjects (Camerino et al., 2019; Prat et al., 2019) and teacher communication (Castañer et al., 2016), no study has yet used the observational methodology to find exactly what happens when physical activity is included in the classroom, that is, what it is and how it is done during the course of the classes.

The main objective of the study was to apply an innovative intraclass active breaks programme to find out and assess how the teacher implements it and how close they come to the plan, the characteristics of the proposed activities and the responses that these generate in the students during the proposed period of physical activity.

Methodology

Design

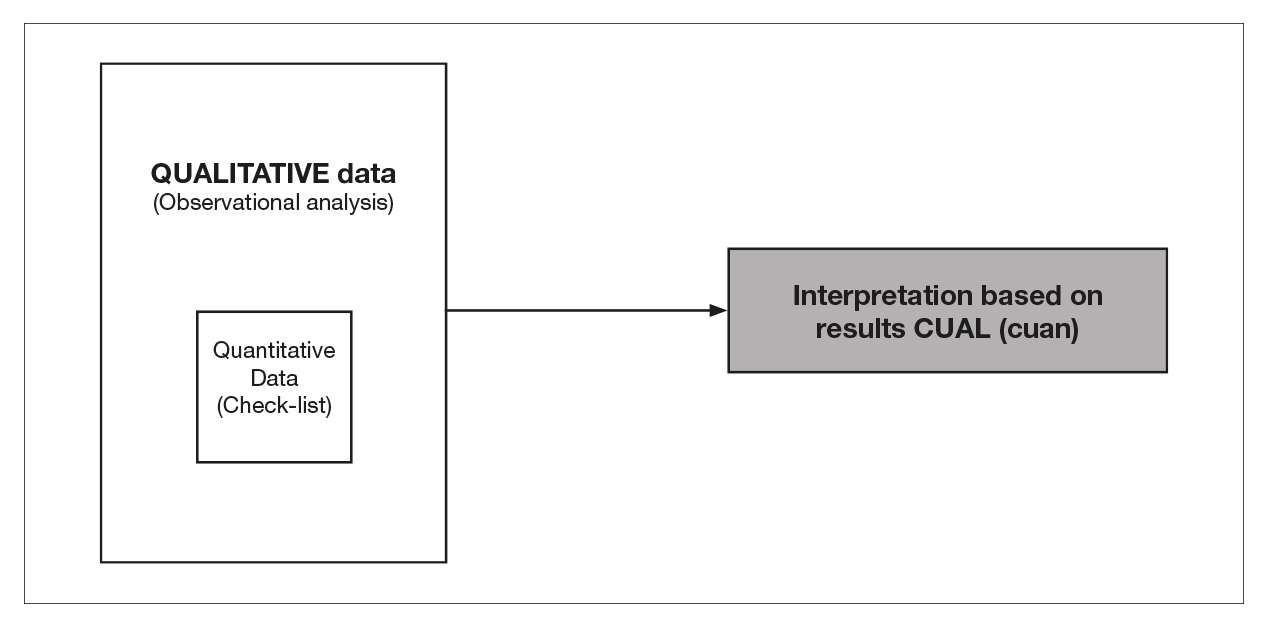

This research was carried out using a mixed methods approach to achieve a greater global understanding of the implementation of an educational and teaching programme (Camerino et al., 2012; Castañer et al., 2013) based on active breaks. Therefore, it was a descriptive, inferential, cross-sectional study using a mixed methodology that was developed using a nomothetic observational design (Anguera et al., 2011), multidimensional (N/S/M) idiographic and with monitoring: a) idiographic, when observing teacher interventions and student interaction in all sessions; b) monitoring, by taking into account the evolution of the teacher’s and the students’ responses throughout the programme, and c) multidimensional, by wanting to analyse various relevant factors reflected in a multiplicity of criteria in the observation instrument. The prevalence of observational data derived from the video recording and analysis of all the sessions configured an embedded model of pervasiveness in the management of results (Figure 1), whose purpose is to work with a dominant type of data, in this case qualitative (observational analysis), while looking for other data, as secondary support, in this case quantitative (an assessment check list), which play a complementary role and are subordinate to the former (Castañer et al., 2013). In addition, these authors indicate that these are the most appropriate when conducting complex longitudinal studies, the main characteristics of this research.

Participants

This research was carried out in a primary education centre in the north-east of the Murcia region (Spain). The sample was selected for convenience and accessibility, using entire primary education classes, which consisted of:

(1) Teachers: teacher-tutor (with more than 10 years of experience as a teacher) of a 6th year of primary school who taught various subjects (Mathematics, Social Sciences, Natural Sciences, Applied Knowledge and Spanish Language) and implemented an active breaks programme. The content prepared by the teacher in each of the areas, within the curriculum of the Spanish educational system, were included in the current Spanish educational system (LOMCE, 2013).

(2) Students: the sample consisted of a total of 26 participants aged between 11 and 13 years (M = 11.73; SD = 1.73), who presented a medium-low socio-economic level. None of the students had previous experience with active breaks.

Instruments

To corroborate the effects of the implementation of a methodology in the educational field, Hastie and Casey (2014) establish that one of the key elements that the research group must provide is the validation of the methodology or strategy to be implemented in the study. For this research, this was done by means of an ad hoc checklist for the active breaks of the filmed sessions.

(1) Instrument to assess the active breaks (IEDA): the check list was created from the guidelines given by Muñoz-Parreño (2020) on the elements that the active breaks should contain to assess the teaching strategies based on the active breaks. It consists of eight items, which were completed by binary (Yes-No) responses, depending on whether or not the strategies under observation were applied during the PA integration period in the classroom (5′-10′). The ad hoc checklist consisted of the following items: 1) class interruption (CI), 2) movement (MOV), 3) academic content (AC), 4) social interaction (SI), 5) session structure (SE), 6) motivation (MO), 7) participation/activation (PA), and 8) cooling down (CD).

(2) Instruction-oriented active breaks observation instrument (SODAE): this instrument was created to record the behaviour and generate behaviour patterns of the teachers and students in the active break implementation sessions in the classroom. The instrument consisted of an observation system consisting of six criteria, the first three adapted from the OSMOSTI observation instrument (Observational System of Motor Skills, Space, Time and Interaction) (Castañer et al., 2020) and the other three following the proposals of Muñoz-Parreño (2020). The criteria are related to the proposal and structuring of the active breaks. The teacher role covers the criteria: (1) motor skills, (2) social interaction, and (3) use of space. A criterion related to the performance of the students: (4) student participation, and two criteria related to the characteristics of the active breaks: (5) academic content and (6) cognitive resolution. All of this instrument’s criteria fulfilled the criteria of completeness and mutual exclusivity of any observation system. A total of 21 categories were included (Table 1).

Table 1

Observation system for active breaks in teaching, SODAE, adapted from the OSMOSTI system (Observational System of Motor Skills, Space, Time and Interaction) (Castañer et al., 2020).

Next, we will lay out the steps prior to the implementation and development of the intervention program.

Previous active break training of the teachers

To implement any type of educational programme, specific professional development of the teachers is needed (Lee and Choi, 2015). Along these lines, Pozo et al. (2018) highlight two aspects that research should have: (1) requirement for expert checking and assessment of the intervention, and (2) continuous and close monitoring of the data in the implementation of longitudinal studies, as well as including ad hoc methodological designs. The teaching staff were trained in active breaks, using a two-phase approach:

(1) Initial training: a 5-hour theoretical-practical course on active breaks was given, in which the method for adapting physical exercise to the teaching programme for the various subjects was explained to the teachers and they were provided with global and specific strategies for how to incorporate physical activity into the classroom.

(2) Continuous training: initially, the teacher had to deliver a document describing the approach of three active breaks integrated into sessions that had a link with to any of the educational areas they taught. The principal investigator provided comments and suggestions on their proposal. Subsequently, the main researcher met every week with the teacher in order to learn about the development of the programme and provide feedback to the teacher about which aspects that they carried out correctly and which could be improved. This information was transmitted thanks to the analysis of the recorded sessions, the results of which were reflected and delivered to the teacher in the weekly meetings, through a report.

Procedure and intervention

Permission was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia (ID: 3207/2021). The project was then presented to an educational centre in the Mar Menor region, its management team and teachers were informed about the objectives and their collaboration was requested. Finally, informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all study participants, in accordance with the ethical guidelines for consent, confidentiality and anonymity of the responses.

After designing the intervention and providing the teacher with all the necessary training in active breaks in the aforementioned training, the intervention of the active breaks educational program began during the planned 12 weeks, based on an active teaching methodology and following the same content as the educational centre’s teaching programme, as established in the curriculum for each of the subjects in which it was implemented (Mathematics, Social Sciences, Natural Sciences, Applied Knowledge and Spanish Language).

In the development of the sessions, three different active break methods were used:

(1) Tabata routines (Tabata et al., 1996), which consisted of a combination of six exercises performed at maximum intensity (e.g.: squats, table push-ups, etc.), with rest periods (Koch, 2004), following the proposal of Muñoz-Parreño et al. (2020). They were used for five days a week, at least once a day. In this case, they were performed throughout the intervention, following a progression of the training load.

(2) Active videos of physical involvement or Brain Breaks Videos (Hidrus et al., 2020), based on the physical mimicry by the students of audiovisual resources projected on the classroom’s digital blackboards (e.g.: dances, movements, etc.). This method was also used for five days a week, at least once a day.

(3) Active break with cognitive involvement related to curricular reinforcement (Abad et al., 2014), following the proposal of Solís-Antúnez (2019) on physical exercises in which the curricular content of various knowledge areas is worked at the same time such as Spanish language, mathematics, social sciences, applied knowledge and natural sciences. They were used for two to three times a week, only once a day.

The application of the programme followed a progression in difficulty and the physical exercise load during the active break, especially those in which the Tabata routines were applied. In the first month, routines were carried out in which they worked for 15″ and rested for 15″. In the following four weeks, resting time was reduced by 5” while motor involvement was maintained (15″ -10″). Finally, during the last four weeks the working time was increased and the resting time was maintained (20″-10″).

Analysis of the results

A total of 23 sessions were analysed, with a total duration of 55 minutes per session. Two observers, graduates in Physical Activity and Sports Sciences, were trained by experts in observational methodology, following the guidelines established by Wright and Craig (2011). The interobserver reliability before the beginning of the data analysis for the use of the ad hoc checklist was 89.1% and for SODAE, 95% (García-López et al., 2012).

Regarding the processing of the results of the IEDA instrument, a descriptive statistic was chosen, with a calculation of the percentages of each of the strategies used by the teacher (class interruption, movement, academic content, social interaction, structure, motivation , participation/activation, cooling down, application) in the implementation of the programme and its progression during the 12 weeks from its beginning to its end.

To find the most significant teaching behaviours and the response they triggered in the students throughout the educational programme, a detailed visualisation, analysis and recording of ten sessions, representative of each period and randomly selected, was carried out. The LINCE PLUS program and recording instrument (Soto et al., 2019) was used, the results of which were exported in .txt format for analysis to find temporal patterns (T-patterns), with the THEME v. 6 program. (Magnusson, 2000).

Results

Verification of teaching strategies and student responses (IEDA)

The IEDA results showed the progression of the active break-based teaching strategies used by the teacher throughout the intervention (Table 2). Specifically, they showed the differences between the strategies applied by the teacher in the active breaks for each of the weeks of the study. Table 2 shows some results in which it can be seen that the teacher experienced a progressive improvement in the implementation of the active breaks as the intervention progressed. All of this is reflected in the total strategy application percentage in week 1 (66.7%), week 2 (62.5%), week 3 (75%), week 4 (81.3%), week 5 (79.2 %), week 6 (81.3%), week 8 (91.7%), week 10 (95.8%) and week 12 (100%). In almost all of them a progressive improvement is seen, except in 2 and 5, in which it is reduced, and in 6, which is the same as week 4. In addition, a significant percentage difference is observed between the teaching strategies incorporated in the active breaks of week 1 (66.67%) and week 12 (100%).

Table 2

IEDA results, showing the percentages of the strategies used by the teacher throughout the programme.

The total strategy application percentage, throughout the intervention, was above 60%. And after week 2, the percentages did not drop below 75%, and were even above 90% in weeks 8, 10 and 12. Thus, an increase in the fidelity in the implementation of the active breaks was verified.

The most applied strategies during the active periods in the intervention were social interaction, movement, structure, participation and the cooling down, with 100% implementation in the active breaks analysed. The variables social interaction and motivation, both at 56.5%, and academic content (34.8%) were those that were applied least often, especially at the beginning of the study, an aspect that improved in the final weeks of the programme.

Teaching performance and student response (SODAE)

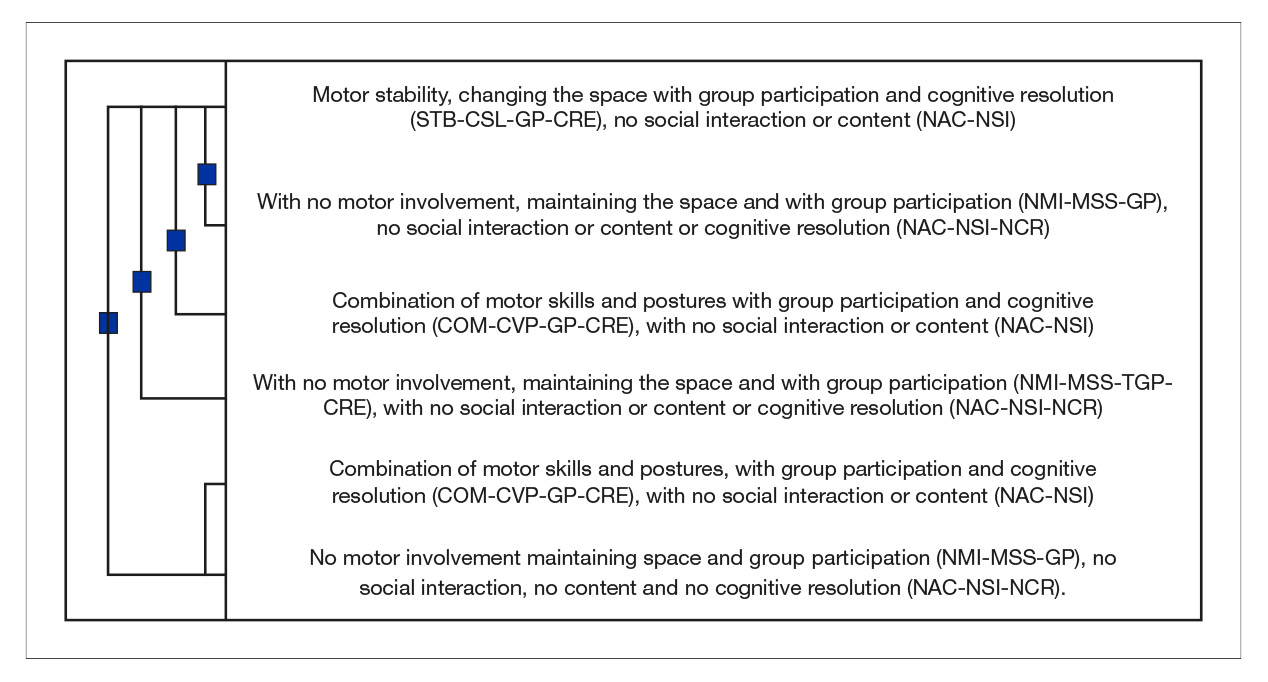

The analysis of temporal patterns shows that the teacher, during the intervention, followed various sequenced and typical behaviours. In the dendrogram (Figure 2) it can be seen that a combination is proposed in which a stability (SPE) physical exercise is proposed in which there is no social interaction (NSI), there is a change in the spatial level (CEE), works the entire group (WEG), the academic content is not reinforced (NAC), but the cognitive resolution (CR) is reinforced, which is preceded by a rest period in which the students recover for the next metabolic effort (NIM-NSI-MME-WEG-NAC-NCR). After this sequenced behaviour, a physical exercise reappears in which motor skills (CMS) are combined, without NSI, with a combination of postures (CVP), in which WEG, without NAC reinforcement and with CR, which is once again preceded by a period of rest (NIM-NSI-MME-WEG-NAC-NCR). Thus, it can be said that the structure proposed by the teacher to implement the active breaks is repeated consecutively while it lasts (5-10 minutes).

Discussion

The general objective of this study was to apply an active break programme in the classroom to find its results in terms of the characteristics of the exercises proposed and the responses produced in the students during the period of physical activity, as well as to assess the degree of fidelity of the implementation.

The results of this study show that the active breaks applied by the teacher have moments of motor resting that occur primarily in the Tabata protocol, in which an active exercise is doe for 20” (e.g. skipping) and rests for 10”. When comparing the results with other studies, it should be noted that there are no precedents to date in which active breaks have been evaluated using a mixed methods approach based on the observational methodology (Chacón-Cuberos et al., 2020). During this PA period, the main exercises incorporated by the teacher were combinations of motor skills (e.g. push-ups) and those involving stabilisation (e.g. squats). This type of active break has also been applied in quantitative methodology studies, such as that of Muñoz-Parreño (2020), in which very positive results were obtained in increasing the level of PA, in school and after school, of students at the school.

In addition, the results show that the teacher applied various organisations to promote social interaction, alternating between individual performances and large group collaborations, which allowed the students to be in continuous contact. These results agree with the line of research, such as those of Muñoz-Parreño (2020) and Solís-Antúnez (2019), based on the incorporation of active breaks in primary education through cooperative games and which found positive effects related to the attitude and behaviour of the students in the classroom. Regarding the use of space, the results reflect an alternation between maintaining the space and combining variations in posture (changes in direction and spatial level) throughout the intervention, an aspect that is related to the criterion of social interaction used by the teacher.

On the other hand, this study shows that the academic content was not worked on continuously during the intervention, instead the use of Tabata protocols and active videos predominated. However, the activities proposed by the teacher did involve the students’ motor and cognitive centres in their performances. Along these lines, the study by Suárez-Manzano et al. (2018), in which educational interventions based on active breaks were analysed, found that, in 78% of the interventions carried out, students improved their cognitive function of paying attention in class.

Regarding the response of the students in the active breaks, the results show that they participated and were fully involved during the proposed exercises. Therefore, their response was very positive to the incorporation of PA in the classroom. This evidence allows students to be active and achieve a high percentage of the minimum PA proposed by the WHO (2016), as well as allowing them to acquire healthy lifestyle habits that they can transfer outside the school environment. These results agree with other studies (Fairclough et al., 2012; Muñoz-Parreño, 2020; Solís-Antúnez, 2019) that found a high participation by the students and in which the physical activity recorded during the active breaks made it possible to cover 50% of the WHO’s recommendations.

Regarding the second objective, the data obtained from the IEDA on the teaching of active breaks were used with the aim of finding the level of fidelity of the implementation, since the interpretation of the results of the studies does not depend solely on verifying whether the intervention was properly implemented, but it is also necessary to find those aspects that were carried out in a more ideal way (Durlak and DuPre, 2008). The results show that the teacher experienced a progression throughout the intervention, beginning with the application of 66.67% of behaviours and ending with 100%. This aspect is very interesting, since it is possible to observe the fidelity achieved by the teacher in the methodological strategies for promoting physical activity in the classroom, after initial training, and the importance of continuous training to ensure a good implementation of strategies during programme development. This can be corroborated by previous studies (Camerino et al., 2019) that highlight continuous training as a key element in the application of innovative methodologies in pedagogical models.

The most valued strategies during these active breaks were class disruption, movement, structure, participation, and cooling down. The variables academic content, social interaction and motivation at the beginning of the intervention were implemented less frequently, an aspect that increased as the intervention progressed. However, there is no scientific evidence with which these results can be compared, since no study to date has evaluated the incorporation of PA in the classroom using a qualitative observational methodology. Most have used quantitative methods, such as accelerometers (Watson et al., 2017b; Watson et al., 2019), which do not allow these types of variables to be observed.

Therefore, this instrument (IEDA) was integrated into the mixed methods approach with the aim of finding which behaviours the teacher used to promote physical activity in the classroom, as well as to carry out a continuous evaluation of the intervention (Hemphill et al., 2015) and verify the viability of the educational programme.

However, the lack of results from previous studies that allows them to be compared has to lead us to be cautious in our conclusions, since there is not yet any scientific evidence in line with this study. For this reason, more studies are needed to investigate the behaviours that active breaks produce in students, taking into account the type of strategy used by the teacher (such as the type of active breaks, their duration and intensity), as well as the consequences for other variables, such as the level of physical activity, measured with highly accurate and reliable instruments (e.g. accelerometers), and quasi-experimental designs with randomised samples.

Conclusions

In line with the objectives proposed for this study, it is concluded that the teacher, during the application of the active breaks programme, mainly used the combination of motor skills and variations in posture through individual and large group organisation. The Tabata protocol, in which a period of active time was preceded by a motor rest, seems to be the intraclass activity method most used by the teacher, which proved to be very effective for the participants.

The results of the IEDA instrument show that the teacher applied, in a progressive and suitable way, the strategies that characterise the active breaks, which favoured the participation and motivation of the students, which are confirmed by the teacher’s performance and the students’ responses in the intervention sessions analysed with the SODAE system.

These active pauses predispose students to greater attention and lead to cognitive resolution that promotes full group participation and interaction. Finally, regarding the degree of fidelity to the active break strategies, there is a positive progression on the part of the teacher over time, thanks to factors such as initial training, the continuous training process and the experience acquired in the use of the teaching methodology.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support of the national REDES project: RIPIAFE. Research Network for the Promotion of Physical Activity in Education, as well as the national Means of integration between qualitative and quantitative data subproject, development of the multiple case, and synthesis as main axes for innovative future in research on physical activity and sport [PGC2018-098742-B-C31] (2019-2021) (Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities/State Research Agency/European Regional Development Fund), which is part of the coordinated New approach to research in physical activity and sport from a mixed methods perspective (NARPAS_MM) project [SPGC201800X098742CV0]. We are also grateful for the support of the consolidated research group of the Generalitat de Catalunya GRID [(Design Research and Innovation Group) – Multimedia and digital technology and application to observational designs. 2017 SGR 1405]. This research is supported by an FPU19/04318 (University Teacher Training) contract.

References

[1] Abad, B., Cañada, D. y Cañada M. (2014). Descansos activos mediante ejercicio físico (Dame 10). Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deportes.

[2] Anguera, M. T., Blanco-Villaseñor, A., Hernández-Mendo, A. y Losada, J. L. (2011). Diseños observacionales: ajuste y aplicación a la Psicología del Deporte. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 20(2), 337-352.

[3] Blanco, M., Veiga, O. L., Sepúlveda, A. R., Izquierdo-Gómez, R., Román, F. J., López, S. y Rojo, M. (2020). Ambiente familiar, actividad física y sedentarismo en preadolescentes con obesidad infantil: estudio ANOBAS de casos-controles. Atención Primaria, 52(4), 250-257.

[4] Camerino, O., Valero-Valenzuela, A., Prat, Q., Manzano-Sánchez, D. y Castañer, M. (2019). Optimizing education: A mixed methods approach oriented to teaching personal and social responsibility (TPSR). Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1439. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01439

[5] Camerino, O., Castañer, M. y Anguera, T. M. (2012). Mixed Methods Research in the Movement Sciences: Cases in Sport, Physical Education and Dance, Routledge, UK, 2012. doi.org/10.4324/9780203132326

[6] Castañer M., Aiello, S., Prat Q, Andueza, J., Crescimanno, G. and Camerino O. (2020). Impulsivity and physical activity: A T-Pattern detection of motor behavior profiles. Physiology & Behavior, 219, 112849. doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.112849

[7] Castañer, M., Camerino, O., Anguera, M. T. y Jonsson, G. K. (2010). Observing the paraverbal communicative style of expert and novice PE teachers by means of SOCOP: a sequential analysis. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 5162-5167. doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.839

[8] Castañer, M., Camerino, O. y Anguera, M. T. (2013). Métodos mixtos en la investigación de las ciencias de la actividad física y el deporte. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 112, 31-36. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2013/2).112.01

[9] Castañer, M., Camerino, O., Parés, N. & Landry, P. (2011). Fostering body movement in children through an exertion interface as an educational tool. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 28, 236-240.

[10] Castañer, M., Camerino, O., Anguera, M. T. y Jonsson, G. K. (2016). Paraverbal Communicative Teaching T-Patterns Using SOCIN and SOPROX Observational Systems, In Discovering Hidden Temporal Patterns in Behavior and Interaction, eds M.S. Magnusson, J. K. Burgoon, and M. Casarrubea (New York, NY: Springer), 83-100.

[11] Chacón-Cuberos, R., Zurita-Ortega, F., Ramírez-Granizo, I., & Castro-Sánchez, M. (2020). Physical Activity and Academic Performance in Children and Preadolescents: A Systematic Review. Apunts. Educación Física y Deportes, 139, 1-9. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.20140983.es.(2020/1).139.01

[12] Creswell, J. W. y Plano Clark, V. L. (2007). Designing and conducting Mixed Methods research. CA: Sage. doi.org/10.1177/1558689807306132

[13] De Greeff, J. W., Bosker, R. J., Oosterlaan, J., Visscher, C. y Hartman, E. (2018). Effects of physical activity on executive functions, attention and academic performance in preadolescent children: a meta-analysis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 21(5), 501-507. doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2017.09.595

[14] Durlak, J. A. y DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3-4), 327-350. doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

[15] Dyrstad, S. M., Kvalø, S. E., Alstveit, M. y Skage, I. (2018). Physically active academic lessons: acceptance, barriers and facilitators for implementation. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1-11. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5205-3

[16] Fairclough, S. J., Beighle, A., Erwin, H. y Ridgers, N. D. (2012). School day segmented physical activity patterns of high and low active children. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 406. doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-406

[17] García-López, M., Gutiérrez, D., González-Víllora, S. y Valero-Valenzuela, A. (2012). Cambios en la empatía, el asertividad y las relaciones sociales por la aplicación del modelo de instrucción educación deportiva. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 21(2), 0321-330.

[18] Hastie, P. A. y Casey, A. (2014). Fidelity in Models-Based Practice Research in Sport Pedagogy: A Guide for Future Investigations. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 33, 422-431. doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2013-0141

[19] Hemphill, M. A., Templin, T. J. y Wright, P. M. (2015). Implementation and outcomes of a responsibility-based continuing professional development protocol in physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 20(3), 398-419.

[20] Hernández, L.A., Ferrando, J.A., Quilez, J., Aragones, M., TerrerHernández, L.A., Ferrando, J.A., Quilez, J., Aragones, M., Terreros, J.L. (2010). Análisis de la actividad física en escolares de medio urbano. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Deportes.

[21] Hidrus, A., Kueh, Y. C., Norsaádah, B., Chang, Y. K., Hung, T. M., Naing, N. N. y Kuan, G. (2020). Effects of Brain Breaks Videos on the Motives for the Physical Activity of Malaysians with Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2507. doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072507

[22] Koch, A. (2004). The Secret Of Tabata. Men’s Fitness, 20(5), 142-148.

[23] Langford, R., Bonell, C., Jones, H., Pouliou, T., Murphy, S., Waters, E., Komro, K., Gibbs, L., Magnus, D. & Campbell, R. (2015). The World Health Organization’s Health Promoting Schools framework: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1360-y

[24] Lee, O. & Choi, E. (2015). The influence of professional development on teachers’ implementation of the teaching personal and social responsibility model. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 34(4), 603-625. doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2013-0223

[25] Magnusson, M. S. (2000). Discovering hidden time patterns in behavior: T-patterns and their detection. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers, 32, 93-110. doi.org/10.3758/BF03200792

[26] Masini, A., Marini, S., Gori, D., Leoni, E., Rochira, A. & Dallolio, L. (2020). Evaluation of school- based interventions of active breaks in primary schools: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 23(4), 377-384. doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2019.10.008.

[27] Méndez-Giménez, A. (2020). Resultados académicos, cognitivos y físicos de dos estrategias para integrar movimiento en el aula: clases activas y descansos activos. SPORT TK-Revista EuroAmericana de Ciencias del Deporte, 63-74.

[28] Méndez-Giménez, A., & Pallasá-Manteca, M. (2018). Enjoyment and Motivation in an Active Recreation Program. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 134, 55-68. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2018/4).134.04

[29] Muñoz-Parreño, J. A. (2020). Descansos activos y su influencia sobre los procesos cognitivos superiores en Educación Primaria [Tesis Doctoral]. Universidad de Murcia. hdl.handle.net/10201/95864

[30] OMS. (2016). Comisión para acabar con la obesidad infantil. Organización Mundial de La Salud, 3-5. Recuperado de: www.who.int/endchildhood-obesity/es/

[31] Ordóñez, A. F., Polo, B., Lorenzo, A., & Shaoliang, Z. (2019). Effects of a School Physical Activity Intervention in Preadolescents. Apunts. Educación Física y Deportes, 136, 49-61. dx.doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2019/2).136.04

[32] Orsi, C. M., Hale, D. E. y Lynch, J. L. (2011). Pediatric obesity epidemiology. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, 18(1), 14-22. doi.org/10.1097/MED.0b013e3283423de1https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0b013e3283423de1

[33] Poitras, V. J., Gray, C. E., Borghese, M. M., Carson, V., Chaput, J. P., Janssen, I., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Pate, R. R., Connor, S., Kho, M. E., Sampson, M., & Tremblay, M. S. (2016). Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 41(6), 197-236. doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0663

[34] Pozo, P., Grao-Cruces, A. y Pérez-Ordás, R. (2018). Teaching personal and social responsibility model-based programmes in physical education: A systematic review. European Physical Education Review, 24(1), 56-75. doi.org/10.1177/1356336X16664749

[35] Prat, Q., Camerino, O., Castañer, M., Andueza, J. y Puigarnau, S. (2019). The personal and social responsibility model to enhance innovation in physical education. Apunts. Educación Física y Deportes, 136, 83-99. dx.doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es(2019/2).136.06

[36] Ridgers, N. D., Stratton, G., Fairclough, S. J. y Twisk, J. W. (2007). Long-term effects of a playground markings and physical structures on children’s recess physical activity levels. Preventive Medicine, 44(5),393-397. doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.01.009

[37] Riley, N., Lubans, D. R., Morgan, P. J. & Young, M. (2015). Outcomes and process evaluation of a programme integrating physical activity into the primary school mathematics curriculum: The EASY Minds pilot randomised controlled trial. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18(6), 656-661. doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2014.09.005

[38] Sanz Arazuri, E., Ponce de León Elizondo, A., & Fraguela Vale, R. (2017). Adolescents’ Active Commutes to School and Family Functioning. Apunts. Educación Física y Deportes, 128, 36-47. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2017/2).128.02

[39] Sánchez-López, M., Ruiz-Hermosa, A., Redondo-Tébar, A., Visier-Alfonso, M. E., Jiménez- López, E., Martínez-Andrés, M., Solera-Martínez, M., Soriano-Cano, A., & Martínez-Vizcaino, V. (2019). Rationale and methods of the MOVI-da10! Study -a cluster-randomized controlled trial of the impact of classroom-based physical activity programs on children’s adiposity, cognition and motor competence. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 417. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6742-0

[40] Solís-Antúnez, I. (2019). Experiencia de la implementación del programa “descansos activos mediante ejercicio (¡dame 10!)” en educación secundaria obligatoria. Revista Española de Salud Pública, 93, 1-7.

[41] Suárez-Manzano, S., Ruiz-Ariza, A., Lopez-Serrano, S., Emilio J. Martínez, E. J. (2018). Estudios sobre propuestas y experiencias de innovación educativa, Revista de currículum y formación del profesorado, 22(4), 287-304. doi.org/10.30827/profesorado.v22i4.8417

[42] Soto, A., Camerino, O., Iglesias, X., Anguera, M. T., & Castañer, M. (2019). LINCE PLUS: Research software for behavior video analysis. Apunts. Educación Física y Deportes, 3(137), 149-153. dx.doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2019/3).137.11

[43] Schmidt, M., Benzing, V. y Kamer, M. (2016). Classroom-based physical activity breaks and children’s attention: cognitive engagement works! Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1474. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01474

[44] Tabata, I., Nishimura, K., Kouzaki, M., Hirai, Y., Ogita, F., Miyachi, M. y Yamamoto, K. (1996). Effects of moderate-intensity endurance and high-intensity intermittent training on anaerobic capacity and VO2max. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 28, 1327-1330.doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199610000-00018

[45] Timmons, B., LeBlanc, B. Carson, V., Connor, S., Dillman, C., Janssen, I., Kho, M. E., Spence, J. C., Stearns, J. A. & Mark S. Tremblay, S. (2012). Systematic review of physical activity and health in the early years (aged 0-4 years). Applied Physiology Nutrition and Metabolism, 37(4), 773-792. doi.org/10.1139/h2012-070

[46] Valero-Valenzuela, A., Gregorio-García, D., Camerino, O. y Manzano- Sánchez, D. (2020). Hibridación del modelo pedagógico de responsabilidad personal y social y la gamificación en educación física. Apunts. Educación Física y Deportes, 141, 63-74. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2020/3).141.08

[47] Vaquero-Solís, M., Gallego, D. I., Tapia-Serrano, M. Á., Pulido, J. J., & Sánchez-Miguel, P. A. (2020). School-based physical activity interventions in children and adolescents: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 999. doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030999

[48] Watson, A., Timperio, A., Brown, H. y Hesketh, K. D. (2019). Process evaluation of a classroom active break (ACTI-BREAK) program for improving academic-related and physical activity outcomes for students in years 3 and 4. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 633. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6982-z

[49] Watson, A., Timperio, A., Brown, H., Best, K. y Hesketh, K. D. (2017a). Effect of classroom- based physical activity interventions on academic and physical activity outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 114. doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0569-9

[50] Watson, A., Timperio, A., Brown, H. y Hesketh, K. D. (2017b). A primary school active break programme (ACTI-BREAK): study protocol for a pilot cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials, 18(1), 433. doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2163-5

[51] Wright, P. M. y Craig, M. W. (2011). Tool for Assessing Responsability- Based Education (TARE): Instrument development, content validity, and interrater reliability. Measurement. In Physical Education and Exercise Science, 15(3), 204-219. doi.org/10.1080/1091367X.2011.590084

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: July 6, 2021

Accepted: October 1, 2021

Published: January 1, 2022

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en