Dual Careers in Women’s Sports: A Scoping Review

*Corresponding author: Marina García-Solà marina.garcia.sola@uab.cat

Cite this article

García-Solà, M., Ramis, Y., Borrueco, M. & Torregrossa, M. (2023). Dual Careers in Women’s Sports: A Scoping Review. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 154, 16-33. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2023/4).154.02

Abstract

Previous reviews on dual careers (DC) provide findings on athletes in general, without reference to gender and perpetuating the under-representation of women. Therefore, this scoping review focuses only on sportswomen in order to get an overview of the current landscape of DC studies in women’s sport. The methodology is based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis statement and recommendations for scoping reviews. The bibliographic search was carried out in the databases: Web of Science, PsycINFO, Scopus, Pro-Quest and SPORTDiscus. Studies on DC with female participants and publications in scientific journals from 2012 onwards were included, and 19 articles were obtained for the analysis and synthesis of current research on women’s sport and DC. The results reveal a progressive increase in publications on sportswomen and DC, a predominance of combining sport and studies, and a gap in studies on work-life balance and critical transitions in women’s sport. This review makes visible and highlights the research carried out on DC and sportswomen, as well as the effect of androcentrism, gender roles and the lack of points of reference in the sporting context. Although it is evident that DC is inherent to women’s sport, it has traditionally been studied and conceptualised based on male models. Therefore, research on this topic should be carried out in a holistic way, using models adapted to the realities of women’s sport and consciously including the different modes of being a woman.

Introduction

The field of sports social sciences has studied the incorporation, evolution and status of women within this sector for years, as well as the use and perception of the spaces they occupy (Vilanova & Soler, 2008). Research evidence in this area demonstrates how, as they have gained access to the world of sport, far from reproducing masculine behaviours, they have modelled a sporting culture of their own (Martin et al., 2017). This is possibly due to the fact that women project the values acquired through their socialisation (Puig & Soler, 2004). Thus, the progressive increase in women’s sport has been accompanied by “new ways of doing, understanding and relating to sport” (Martin et al., 2017, p. 101).

In the current context, despite this rise in women’s sport, there is a structural inequality of opportunities that limits women’s social agency in the development of a professional sports career (Ronkainen et al., 2020). This means that few women have the privilege of building a career exclusively centred on sport and that, therefore, dual career discourses that promote the compatibility of sport with a parallel work or academic commitment are particularly relevant for young women (Ronkainen et al., 2020).

Dual career (DC) is “a career focused on both sport and study or work” (Stambulova & Wylleman, 2015, p. 1). Depending on the degree of prioritisation, four possible sporting trajectories are described: (a) linear, where the person focuses almost exclusively on their sporting career; (b) convergent, where sport is still prioritised, but is partially compatible with studies or a job; (c) parallel, where sport and studies or work are equally prioritised; and (d) divergent, which occurs when sport and studies or work demand so much from the athlete to the point of being forced to abandon one or the other (Torregrossa et al., 2020). Different works on disengagement and other transitions (e.g. Perez-Rivases et al., 2017a; Torregrossa et al., 2015) indicate that linear and divergent trajectories have negative consequences for the person who pursues them (e.g. dropping out). Moreover, evidence suggests that those individuals – in some cases referred to as “strategists” (Vilanova & Puig, 2016) – who pursue convergent and parallel trajectories are often associated with certain positive benefits: good levels of resilience and mental health (e.g., increased wellbeing, improved life balance; Tekavc et al., 2015; Torregrossa et al., 2015) and DC competences (e.g. emotional awareness, career planning, DC management and social intelligence and adaptability), leading to healthier and more balanced personal development (De Brandt et al., 2018). Moreover, in the long term, they get better jobs and are happier with their lives beyond sport (López de Subijana et al., 2015).

In order to better develop DC, career assistance programmes (CAPs) have been developed around the world with the aim of providing assistance to athletes with career-related aspects of their lives, both in and out of sport, and some even after retirement (Henry, 2013; López de Subijana et al., 2015; Torregrossa et al., 2020). These are based on the holistic sport career model (Wylleman, 2019), which considers the athlete holistically and addresses the development of the individual in different interacting domains (i.e., sport, psychological, psychosocial, academic/vocational, financial and legal; Wylleman, 2019), and provides accompaniment during the transitions that the athlete will experience throughout his/her sporting life.

Research on DC is now a core topic in sport science (Torregrossa et al., 2020), having increased significantly in recent decades (e.g., Stambulova & Wylleman, 2019). This has led to different models of career development that are generally valid and effective in determining transitions that occur in different domains throughout a sporting career. In both European and Spanish contexts, most studies focus on athletes in general, without taking into account the peculiarities of specific contexts and realities (e.g., López de Subijana et al., 2015), although the sport career experience involves both athlete-specific (e.g., gender, age, type of sport) and environmental (i.e., culture and sport context; Stambulova & Alfermann, 2009) characteristics. Some researchers suggest that personal characteristics, including gender, may influence an athlete’s perception and experience of transitions and decision-making (Samuel & Tenenbaum, 2011; Tekavc, 2017). In fact, it has been found that while men and women perceive some challenges and demands in a similar way, there are others, such as the transition to university (Perez-Rivases, et al. 2017a), which are perceived markedly differently (Tekavc, 2017).

Systematic reviews synthesise all available research in a transparent, rigorous and reproducible way, providing a clear and up-to-date understanding of what is already known, what is unknown, and what next steps research should take (Tod et al., 2021). While there are systematic reviews on DC (e.g. Guidotti et al., 2015; Stambulova & Wylleman, 2019), they deal with athletes in general and there are none specific to sportswomen. In the systematic review by Guidotti et al. (2015), no special mention is made of gender, nor is there any mention of sportswomen; in contrast, there is a reference to the state of the art by Stambulova and Wylleman (2019), in which two comparative sentences can be found in the results section with respect to men. Furthermore, in the critical reflections section, major research gaps and future challenges encourage “research and further investigation of individual career pathways, including minority athletes (e.g. women) and transnational athletes” (Stambulova & Wylleman, 2019, p. 85). Both cases exemplify that women are often significantly underrepresented in science in general and specifically in sport psychology (Gledhill et al., 2017), and are considered a minority. Although social change is underway in the European and North American context, sport remains one of the most accentuated pillars of androcentric domination (Rovira-Font & Vilanova-Soler, 2022). The androcentric view that predominates in science means that, according to Kavoura et al. (2012), male athletes are the norm, while female athletes are studied later, on the basis of similarities or differences in relation to them (Cooky, 2016). Along these lines, and according to Ronkainen et al. (2016) and Andersson and Barker-Ruchti (2018), research on DC and women is still limited and needs to be strengthened by further investigation in this field. For this reason, this study aims to conduct a scoping review of the literature on the DC of sportswomen. While previous reviews focus on literature on athlete DC in general, this one focuses on sportswomen and studies that place them at the centre of knowledge construction.

This scoping review aims to provide an overview of the current landscape of research done on women’s DC in sport. After identifying studies on DC and sportswomen and synthetically summarising the characteristics and results, the following question was asked: how has research evolved and what is there in the existing literature on dual careers in sportswomen? It thereby contributes to research by providing the first integrated synthesis of studies on the DC of sportswomen.

Method

The methodology selected was the scoping review which allows for the identification and categorisation of what is known and unknown about a topic, and identifies gaps in the literature, as a starting point for the development of new work and lines of research (Grant & Booth, 2009).

For the development of this review the authors relied on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA; Page et al., 2021) statement and specifically on the PRISMA-ScR extension by Tricco et al. (2018) following the specific criteria for developing this type of review.

Eligibility criteria and search strategy

In order to carry out the review, the following inclusion criteria were taken into account: (a) the studies had to be studies on DC (i.e., sportswomen-students or sportswomen-workers), (b) the participants had to be exclusively sportswomen, (c) the studies had to have been published in scientific journals from 2012 (i.e., the year in which the European Commission established the working guidelines on DC), and (d) they had to have an abstract in English. Finally, as exclusion criteria (a) studies with a mixed or male sample and (b) studies related to the COVID-19 pandemic were not considered.

For the identification of potentially relevant documents, articles published between 2012 and 6 June 2022 were retrieved from the following bibliographic databases: Web of Science (Core collection), PsycINFO, Scopus, Pro-Quest and SPORTDiscus. The search strategy, organisation and combination of terms were determined using the CHIP tool (i.e., Context, How, Issues, Population; Shaw, 2010), grouping keywords and terms related to DC and (female) athletes, designed in English, in order to identify abstracts of studies conducted in any language (see Table 1). The relationship between search terms, databases and articles found is shown in Table A in the annexes. The electronic database search was supplemented by hand searching for documents in reference lists and key journals in the field (Williams & Shaw, 2016).

Identification and selection of relevant studies

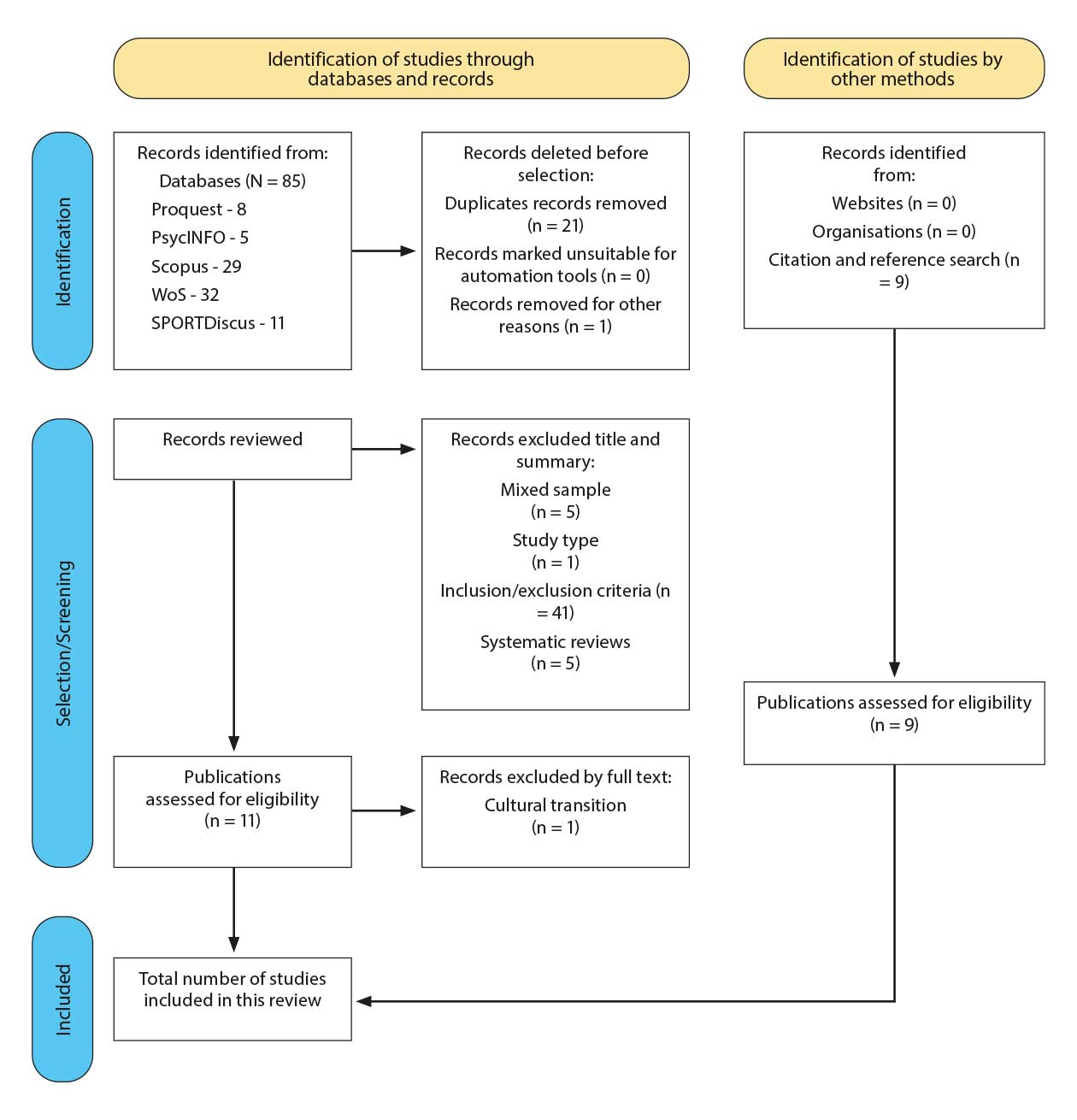

To ensure that the search method was systematic, robust and valid, the three steps proposed by PRISMA were followed: identification, selection and inclusion (Figure 1; Page et al., 2021). Once the potentially relevant studies were identified (i.e., studies derived from the search and pending evaluation), the references and abstracts of each of these were downloaded and stored and organised using the bibliographic management tool Mendeley. After excluding duplicates, the study evaluation was conducted in two phases: first, studies were screened by titles and abstracts, and then full texts were analysed by assessing eligibility and rejecting articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. This process of identification, screening and selection of articles was carried out by the first author of the article, under the supervision of the other authors. To ensure transparency in this process, it is important to record the decisions that have been made using the PRISMA flowchart (see Figure 1; Page et al., 2021).

Coding and data extraction

For data cleaning, a data extraction tool was developed in the form of a table containing the articles included in this review (see Table 2). The table provides information on the key characteristics of the study and details the authorship, year of publication, participants and sport modality, the focus of the study, the design and methodology, and finally the main themes. The first author was responsible for this cleaning, under the supervision of the other authors.

Table 2

Results and characteristics of the identified articles on dual careers and women in sport (N=19).

The included studies were organised in reverse chronological order, so that the most recent studies (i.e., from 2022 to 2012) were listed first. Within each year, they were arranged alphabetically according to the authors’ surnames. In addition, each article has a bibliographic code (see Table 2), which is used in the text (in square brackets) to help with reading the following sections and to distinguish the articles included from other references.

Assessment of the quality of included studies

The quality of the research methodology for the articles ultimately included was assessed by means of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT: Hong et al., 2018). In making this assessment, it is important to use criteria and tools appropriate for the type of evidence being examined (Tod, 2019; Tod et al., 2021). The MMAT is a suitable assessment tool for this work as it is designed for the evaluation of mixed studies (i.e., reviews including qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies). In the MMAT checklist, there are two general questions and five questions for each type of study, to which one must answer “yes”, “no” or “don’t know”. The quality assessment was carried out by the first author, under the supervision of the other authors. Most of the studies were considered to be of high quality, two of medium quality and one of low quality. The quality assessment of all studies can be found in Table B of the Annexes.

Results

As shown in Figure 1, 85 publications were returned from the search of the aforementioned databases. Subsequent to the elimination of duplicates, 63 relevant studies were identified. Based on the title and abstract, 53 were excluded, resulting in 11 articles for full text review, one of which was excluded. In parallel, nine relevant papers were included in the manual search. Eventually, relevant papers were included according to titles, abstracts and full texts, which resulted in a total of 19 studies. The main results and characteristics of interest for each study are presented in Table 2.

The following is a description of the characteristics of DC studies on women (i.e., trend, situation), followed by a narrative synthesis of the extent of knowledge produced in these studies.

Description of study characteristics

As for the publication trend, although it is generally stable, the last three years have seen an upward trend. From 2012, the date of the first article included, to 2019, ten articles have been published with a focus on the DC of sportswomen. This number is almost the same (i.e., nine publications) as the publications made in the last three years (i.e., from 2020 to 2022).

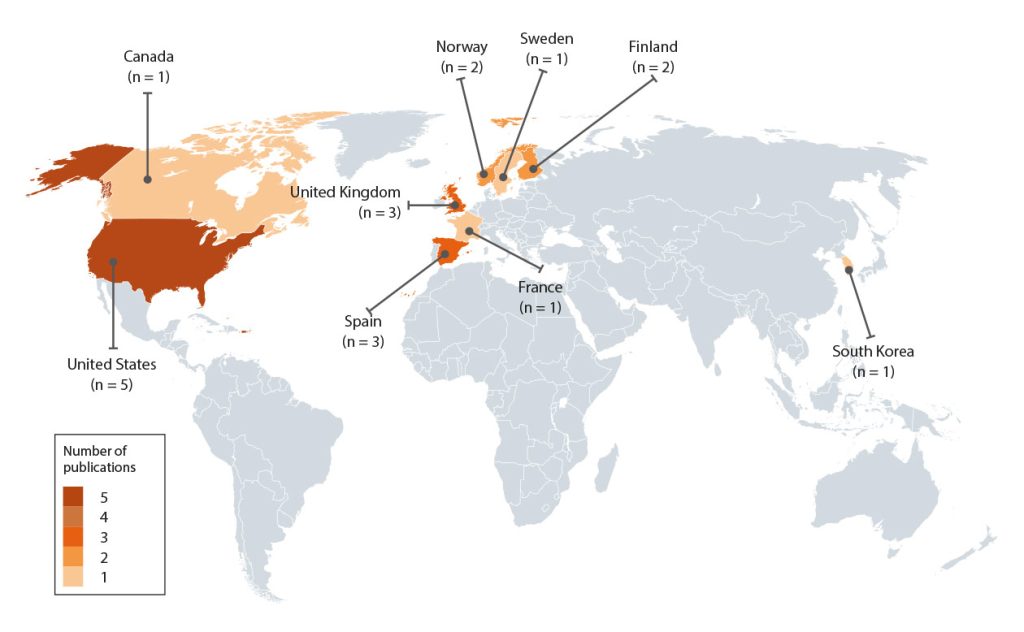

Figure 2 shows an overview of the perspective from which women’s DC has been studied. The 19 studies included were carried out in nine countries on three different continents, countries in the northern hemisphere, mostly in North America and Europe. The country in which women’s DC has been most researched is the United States, with five studies carried out, followed by the United Kingdom and Spain with three and Norway and Finland with two each. In last place, South Korea, France, Sweden and Canada with one study in each country. In terms of language, of the 19 entries, 17 were in English and two in Spanish. Regarding the study participants, most of them are active sportswomen, while only four studies include former sportswomen in their sample [1, 15, 18, 19]. The predominant study design is qualitative and the most commonly used technique for data collection is the semi-structured interview. Exceptionally, there is one study [7] which uses quantitative methodology utilising the Dual Career Competency Questionnaire for Athletes (DCCQ-A; De Brandt et al., 2018), and one study with mixed methodology [1], which combines data collection through an individual interview and a training diary with data on rankings and data from a syllabus.

Depending on the focus of the DC, four studies assess the compatibility of sport and alternative work and focus exclusively on job placement and non-sport career (e.g. barriers and resources to combine sport and work), while the rest (n = 15) assess compatibility with studies and explore more general topics (e.g. management and perception of DC, identity, transitions, CAPs).

With regard to transitions, the transition to university (n = 6) is the one most frequently considered in the studies, followed by the transition from junior to senior (n = 3), followed by the transition from retirement (n = 2) and, finally, the transition from puberty (n = 1).

Finally, it can be inferred from the studies that the majority of sportswomen followed a parallel trajectory (i.e., similar importance placed on sport and studies/work), followed by those sportswomen with a convergent trajectory (i.e., more importance placed on sport than studies/work). Some studies also refer to moments of diverging trajectories (i.e., where sporting and vocational demands conflict and they drop out of sport). Lastly, there is only one study that addresses the possibility of following a linear trajectory as a sportswoman.

Having outlined the evolution of the research and the general characteristics of the studies, it can be seen that the most predominant study profile is that of football players (n = 5), who combine sport with studies (n = 15) and follow a parallel career (n = 16), using a qualitative methodology based on a semi-structured interview (n = 14), where aspects of the management and perception of the DC are dealt with (i.e., barriers and resources, transitions and future planning; n = 17).

Scope of DC studies on women

In this section, a narrative synthesis of the scope of contributions and knowledge on the management and perception of sportswomen’s DC (i.e., barriers and resources, identities and trajectories) is presented.

DC management is often perceived as problematic [3, 5, 8, 11], as in many cases it is difficult to find a balance and a period of adaptation is often necessary to adjust and cope with the different demands [3, 5, 13]. On the one hand, the main perceived barriers are lack of, or poor time management [2, 5, 6, 10, 19], poor time flexibility [1, 2, 5, 11, 18], having to leave home [3, 7, 19], environments with excessive competitiveness or perfectionism [1, 8, 16, 19] and increased sporting and academic demands [3, 5, 11, 12], which, ultimately, they try to compensate for by reducing their social life [7, 12]. On the other hand, the main perceived resources are social support (e.g. colleagues, coaching staff, family and friends) [2, 3, 4, 12, 15, 17, 18], acquired skills (e.g. planning, organisation, ability to sacrifice) [1, 8, 18], motivation and commitment to continue studying [1, 2, 5, 10, 17] and access to institutional resources [2, 5, 7, 9, 10, 18]. In relation to institutional resources, women are often regular users of CAPs and they play an important role in the development of DC [5, 7].

The lack of female role models means that some sportswomen are not able to envisage a path to a professional future in elite sport [6, 16] and, therefore, link their identity as professional sportswomen [5, 6, 14, 16]. However, some studies [3, 10, 11] show that this sport identity is more prevalent, especially in sports that have reached professional status (e.g., women’s football) or high competitive levels (e.g., Division I college sports in the United States). Therefore, in general, women do not tend to develop a single sport identity, but develop multiple alternative identities besides sport (e.g., student identity) [1, 6, 9, 15, 17]. In this sense, when academic demands start to increase, sportswomen start to develop these non-sporting identities [1, 5, 8] and may even decrease their focus on sport and see it as just another hobby [5]. For example, the transition to university is perceived by some as an opportunity to consider and investigate other career options, with the aim of personal and individual development [17]. At this point some begin to follow divergent trajectories, triggering possible abandonment of sport and premature withdrawals [5, 15, 16, 17]. In post-retirement career planning, many women choose to follow traditionally “female” careers because of the pressure to conform to social gender roles and few consider a career path linked to sport [14].

Discussion

This study enables sportswomen to be placed at the centre of the construction of knowledge about DC and to explore a reality that has traditionally been silenced or sidelined. In this way the existing literature has been categorised and trends and gaps in knowledge in this field have been identified.

19 primary studies published in scientific journals between 2012 and 2022 have been identified, the quality of most of which is considered to be high. The growing number of publications on women’s DC is noteworthy. This is in line with the findings of Stambulova and Wylleman’s (2019) state of the art, which suggest a trend of intensifying research within DC discourse. However, it should be noted that most articles are published in European countries or the United States, which only builds knowledge from a Western and Northern perspective. These results are in line with those found in the review by Guidotti et al. (2015), which suggest that states that facilitate the education of talented elite athletes also promote scientific interest in this field of research, but it should be borne in mind that knowledge of women’s DC is being constructed based on hegemonic culture (e.g. white, cisgender, middle-class women) and, for the moment, invisibilising the experiences and knowledge of other women in the world and other modes of being a woman.

The main barriers to DC for sportswomen are associated with poor time management, poor time flexibility, leaving home, environments with excessive competitiveness or perfectionism, and increased sporting and academic demands. These findings reinforce other research on DC more generally, for example, in the study by López de Subijana et al. (2015) or the study by Miró et al. (2018), in which poor time management and little time flexibility are recognised as the main obstacle when undertaking a DC. Complementarily, social support and CAPs stand out as key resources for the development of a DC (López de Subijana et al., 2015).

On a general level, the need to study DC from a broad perspective (i.e., holistic sport career model; Wylleman, 2019), which takes into account the specificity of sportswomen (i.e., predominant transitions and trajectories, role conflicts, lack of professional sport structures, multiple identities crossed by gender roles), has become evident. This implies that it is important to conduct studies that consciously investigate critical transitions in the development and overall experience of sportswomen (e.g. puberty, motherhood, retirement; Debois et al., 2012). The transition to university has been studied both prospectively and retrospectively (Perez-Rivases et al., 2017a), as has occurred in the literature generally (Brown et al., 2015; Defruyt et al., 2020). In both cases, the importance of planning ahead in order to successfully meet the challenge of increased academic and sporting demands is highlighted (Brown et al., 2015; Perez-Rivases et al., 2017a). This transition is particularly critical for women, as there is a high drop-out rate from sport during this period. In contrast, transitions which, generally speaking, in previous literature are highly studied (i.e., transition from junior to senior and retirement; Park et al., 2012; Torregrossa et al., 2016) do not feature prominently in the literature review. According to Ronkainen et al. (2016) there is a gap in the literature on women’s sport careers and few studies have focused on understanding the impact of gender on the career development and retirement processes of sportswomen. As for the critical pubertal transition, there is only one study that considers it. Because of the changes it entails and the perception of the body and physical abilities of sportswomen (Kristiansen & Stensrud, 2017; Tekavc et al., 2015), this is one of the critical transitions that should be strengthened in the research, along with motherhood (Ferrer et al. (2022). All these transitions can be addressed in CAPs so that they occur and are experienced in the healthiest possible way.

Currently, these CAPs are created and designed based on a general model of the athlete (e.g. male, white, middle class), and therefore constructed under the androcentric bias. In fact, from some articles included in the review (Harrison et al., 2020; Perez-Rivases et al., 2020), there is a concern and a call for an improvement in the quality of care afforded to CAPs, specifically that they should be more gender-sensitive and designed to maximise the personal resources of sportswomen, so as to better adapt to the specific demands of their DC (Skrubbeltrang et al., 2020). Many CAPs continue to provide advice beyond their sporting careers, even after retirement (Henry, 2013). In fact, one of their functions is to advise the athlete on how to combine sport with a job and how to find a job during and/or after retirement. This review highlights the scarcity of research focusing on the reconciliation of sport with work or employment after retirement. As noted by Stambulova and Wylleman (2019), there is a lack of data on work-sport balance, and there is a need to put this issue on the research agenda in women’s DC research. This need is also reflected in the recent Position Stand of the International Society of Sport Psychology (ISSP) which sets the challenge of research beyond the sport career in order to study also the employability competences of the athlete, as well as DC combining sport and work (Stambulova et al., 2021). The lack of studies in this area has important repercussions on the development of the sporting career, as it entails overlooking one of the main areas of the athlete’s life.

This vocational area is particularly relevant for women as women’s sport generally has fewer resources and structures (Ronkainen et al., 2020), and many competitions do not have professional status. Although high-level sportswomen can be found competing at national or international level and are paid for their performance (Gladden & Sutton, 2014), most of them have to combine sport and work or retire prematurely from sport because salaries at the professional level alone are not sufficient (Sherry & Taylor, 2019; Skrubbeltrang et al., 2020).

The study and concept of DC emerges as a preventive resource from the withdrawal process based on the logic of professional sport with a linear trajectory. In other words, the DC phenomenon is constructed on the basis of the male athlete with real professional options and, therefore, from an androcentric logic. In contrast, in the results of the study, the majority of sportswomen follow parallel or converging trajectories and this collation is rarely a voluntary decision, but an essential and idiosyncratic fact of women’s sport (Ronkainen et al., 2020). So much so that the possibility of following a linear trajectory as a sportswoman is only mentioned in one study. Sportswomen are aware that, as women, they need education in order to provide them with something to fall back on as an alternative to sport (Harrison et al., 2020). Given this reality, it is important that women’s careers are studied from perspectives adapted to their realities by focusing on the specific stressors, experiences and motivations that women have for pursuing this DC.

As seen in the results of this review, multidimensional identity and sport are highly studied topics. Considering the sportswoman developing DC holistically implies understanding that she is traversed by multiple roles (e.g., gender, student, athlete) and identities, and while these are ultimately a protective factor against withdrawal (Douglas & Carless, 2009; Jordana et al., 2017), what conflicts prioritising multiple domains simultaneously over the course of DC has not been sufficiently explored. Of the articles reviewed, only one attempts to explicitly explain why. Han et al. (2015) suggest that this conflict may arise because they are expected to play a triple role: women, students/workers and sportswomen. On the one hand, and in line with other research (Tekavc, 2017), being an athlete today is still associated with a conventional masculine role that conflicts with the role of being a woman. Furthermore, because of the dual athlete-student identity, in which most women feel more sporty, given that most of their schedule is occupied by training and most of their social relations are within the sporting context (Han et al., 2015). Along these lines, Lee (2012) reports that student-athletes are more distanced from classmates because attendance is less regular and they may spend less time outside school hours. In this sense, the results of some studies included (Falls & Wilson, 2013) are in line with previous studies (Tekavc et al., 2015), which point out that teammates are a crucial source of support for their development and suggest that sport identity is closely linked to the team.

The results of the studies included suggest that the perceived lack of career opportunities, multidimensional identity, the exploration of other interests, the attempt to combine sport and work and the transition to higher education result in the adoption of divergent trajectories (Torregrossa et al., 2020) that lead to a higher probability of dropout and early withdrawal. Specifically, Han et al. (2015) suggest that in the face of a social system with limited opportunity for career choices, when faced with an alternative to sport, sportswomen may consider withdrawal. Previous research follows the same line and warns of the high risk of women retiring prematurely (Skrubbeltrang, 2019) with the main reasons being entering the world of work (Tekavc et al., 2015), receiving a good job opportunity (Stambulova et al., 2007), the low probability of succeeding in a professional sports career (Skrubbeltrang et al., 2020) and motherhood (Tekavc et al., 2020).

When the time comes to retire, the results show that it is difficult for women to continue with a job linked to the world of sport (e.g. coaches, referees, physical trainers). On the one hand, the lack of female role models in these jobs plays an important role in this situation, which may explain why women are not so attracted to this career path (Borrueco et al., 2022). On the other hand, according to Ryba et al. (2015) and seconded by Ronkainen et al. (2016), by socialising as women, sportswomen often feel pressure to adhere to the life path set for them or have to choose between that or sport. This life path dictates that graduation should lead to a full-time job and family (Ronkainen et al., 2016). Therefore, it is common for women to opt to follow traditionally “feminine” careers once they have finished their sporting careers, and their professional aspirations are congruent with the academic training they have obtained (Navarro, 2015). This would exacerbate the shortage of women managers and women in positions of power and leadership in the world of sport (Perez-Rivases et al., 2017b).

In order to provide guidance on how to manage gender-specific aspects of a sporting career (e.g. conflict between sporting agenda and female role, conflict between sporting and academic/vocational agenda, balancing motherhood and sport, critical transitions), so that women’s participation and aspirations in the world of sport can be increased and women’s sport can continue to grow, different female sporting role models need to be made visible as points of reference. Women who act as role models and points of reference are of great importance for the construction of identity because they provide examples that can be reflected upon. For example, Han et al. (2015) report athletes lamenting the lack of female role models for women with DC trajectories and career paths in sport. Along the same lines, there is also a lack of women in different leadership positions in the world of sport (Borrueco et al., 2022; Perez-Rivases et al., 2017b). For this reason, it is essential that academia constructs and makes visible narratives that are close to their identities and needs and that allow them to be guided towards action (Ronkainen et al., 2019). Only in this way will it be possible that in the future the different ways of doing, understanding and relating to sport that women bring to the table will form part of and nourish the socialisation of future generations of sportsmen and women.

Limitations and future lines of research

This study is not without limitations, among which it is worth highlighting that approximately half of the articles included in the review come from manual searches in other sources, when usually the majority of the articles included come from systematic searches in databases. One possible reason for this anomaly is that the subject of study is not currently mainstream. This often means that even if there are studies on the topic of interest, they are difficult to find through systematic database searches with the search engines used. This is knowledge that must be explored, and which is invisible due to the lack of relevance given to both the results and the conclusions drawn, as a result of the androcentrism that predominates in science. For this reason, while the scoping reviews are comprehensive, it is possible that some relevant studies may have been omitted. Finally, a potential limitation is that the scope of the results only allows for the description of the development of DC for women in general. Given the characteristics of the samples of the included studies, there is a lack of specific articles that explore and incorporate the experiences of all types of women, specifying the different axes of oppression that affect them (e.g. race, culture, sexual orientation, abilities -intersectionality-; Collins, 2015).

Therefore, it is recommended that beyond increasing the amount of research that explores the identified gaps in women’s DC (e.g. sport-work balance, the concept and status of professionals in women’s sport, the lack of role models, women’s motivation towards DC), future research should also include and take into account diversity among women. In this way, future research designs should be sensitive to intersectionality which is understood as the “web of intersecting relations” considering various forms of oppression (e.g. race, sexuality, nationality) that intertwine with each other and co-construct people’s lived realities (Collins, 2015). This will make it possible to visualise different realities and experiences of women undertaking a DC and to broaden the diversity of points of reference. Finally, this review provides an overview of the state of the literature in this area. At the same time, it allows for the detection of the studied population’s needs in order to develop future actions that raise awareness in society and enable the implementation of egalitarian practices. This implementation is necessary at different levels: in the management of sport by institutions and sports federations (i.e., equal opportunities, resources and visibility); in the work of professionals linked to clubs and sports centres, in order to make the experience of sportswomen as healthy as possible (e.g. advice in CAPs). This is why it is necessary that research and application move in the same direction.

Conclusions

This scoping review has provided an overview of the current research landscape on DC and sportswomen. In this way, a new door is opened to women’s sport with the aim of enriching and increasing research and the representation of women in this field. The results reveal that most of the perceived barriers and resources are the same as those in research in general, but due to socialising as a woman, the way of experiencing, understanding and relating to sport is different. The multiple identities developed (e.g. athlete, woman, student/worker), combined with the male-dominated context in which sportswomen find themselves and strong gender roles in society, trigger role conflicts that often lead to discomfort and premature withdrawal. The main mechanism that accounts for many of the gaps identified in the literature and the need to study the careers of sportswomen from points of view adapted to the everyday life of women’s sport is androcentrism. In this sense, this pioneering review becomes a seed from which to grow knowledge that attempts to carefully describe the realities of women’s sport from a holistic perspective. This will open up new branches of research to generate knowledge from which women leave the margins and become the centre, overcoming their under-representation and the current androcentrism of sport psychology.

Declarations

Acknowledgements/Funding. This work was supported by the Generalitat de Catalunya through the grant FIN-DGR 2021 (2021 FI_B 00352), the project Promotion of Healthy Dual Careers in Sport (RTI2018-095468-B-100) funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and the REFERENTE Network for the promotion of the professional careers of female referees, judges and coaches (05/UPR/21).

References

[1] Andersson, R., & Barker-Ruchti, N. (2018). Career paths of Swedish top-level women soccer players. Soccer & Society, 20(6), 857-871. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2018.1431775

[2] Bergström, M., Solli, G., Sandbakk, O., & Sæther, S. (2022). “ Mission impossible ”? How a successful female cross-country skier managed a dual career as a professional athlete and medical student: a case study. Scandinavian Sport Studies Forum, 13, 57-83. https://sportstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/sssf-vol-13-2022-p57-83-bergstrometal.pdf

[3] Borrueco, M., Torregrossa, M., Pallarès, S., Vitali, F., & Ramis, Y. (2022). Women coaches at top level: Looking back through the maze. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 0(0), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541221126614

[4] Brown, D. J., Fletcher, D., Henry, I., Borrie, A., Emmett, J., Buzza, A., & Wombwell, S. (2015). A British university case study of the transitional experiences of student-athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 78-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.04.002

[5] Collins, P. H. (2015). Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142

[6] Cooky, C. (2016). Feminisms. In B. Smith & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise Psychology (pp. 75-87). Oxon, New York: Routledge International Handbooks.

[7] Cooper, J. N., & Jackson, D. D. (2019). “They Think You Should Be Able to Do It All:” An Examination of Black Women College Athletes’ Experiences with Role Conflict at a Division I Historically White Institution (HWI). Journal of Women and Gender in Higher Education, 12(3), 337-353. https://doi.org/10.1080/26379112.2019.1677250

[8] De Brandt, K., Wylleman, P., Torregrossa, M., Schipper-Van Veldhoven, N., Minelli, D., Defruyt, S., & De Knop, P. (2018). Exploring the factor structure of the dual career competency questionnaire for athletes in european pupil- and student-athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2018.1511619

[9] Debois, N., Ledon, A., Argiolas, C., & Rosnet, E. (2012). A lifespan perspective on transitions during a top sports career: A case of an elite female fencer. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(5), 660-668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.04.010

[10] Defruyt, S., Wylleman, P., Kegelaers, J., & De Brandt, K. (2020). Factors influencing Flemish elite athletes’ decision to initiate a dual career path at higher education. Sport in Society, 23(4), 660-677. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1669324

[11] Douglas, K., & Carless, D. (2009). Abandoning The Performance Narrative: Two Women’s Stories of Transition from Professional Sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 21(2), 213-230. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200902795109

[12] Falls, D., & Wilson, B. (2013). “Reflexive modernity” and the transition experiences of university athletes. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 48(5), 572-593. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690212445014

[13] Ferrer, I., Stambulova, N., Borrueco Carmona, M., & Torregrossa, M. (2022). Maternidad en el tenis profesional:¿es suficiente con cambiar la normativa? Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 22(2), 47-61. https://doi.org/10.6018/cpd.475621

[14] Frederickson, K. (2022). Dual Collegiate Roles—The Lived Experience of Nursing Student Athletes. Journal of Nursing Education, 61(3), 117-122. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20220109-01

[15] Gladden, J., & Sutton, W. (2014). Professional sport. In P. M. Pederson & L. Thibault (Eds.), Contemporary Sport Management (pp. 218-239). Champaign: Human Kinetics.

[16] Gledhill, A., & Harwood, C. (2015). A holistic perspective on career development in UK female soccer players: A negative case analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 65-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.04.003

[17] Gledhill, A., Harwood, C., & Forsdyke, D. (2017). Psychosocial factors associated with talent development in football: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 31, 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.04.002

[18] Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

[19] Guidotti, F., Cortis, C., & Capranica, L. (2015). Dual career of European studentathletes: a systematic literature review. Kinesiologia Slovenica, 21(3), 5-20. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1773262744?accountid=15292

[20] Han, S., Kwon, H. H., & You, J. (2015). Where are We Going?: Narrative Accounts of Female High School Student-Athletes in the Republic of Korea. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 10(6), 1071-1087. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.10.6.1071

[21] Harrison, G. E., Vickers, E., Fletcher, D., & Taylor, G. (2020). Elite female soccer players’ dual career plans and the demands they encounter. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34(1), 133–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2020.1716871

[22] Henry, I. (2013). Athlete development, athlete rights and athlete welfare: A European Union perspective. International Journal of the History of Sport, 30(4), 356-373. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2013.765721

[23] Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., & Vedel, I. (2018). Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (version 2018). Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/232

[24] Jordana, A., Torregrosa, M., Ramis, Y., & Latinjak, A. T. (2017). Retirada del deporte de élite: Una revisión sistemática de estudios cualitativos. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 26, 68-74. https://archives.rpd-online.com/article/view/v26-n6-jordana-torregrosa-ramis-etal.html

[25] Kavoura, A., Ryba, T., & Kokkonen, M. (2012). Psychological research on martial artists: A critical view from a cultural praxis framework. Scandinavian Sport Studies Forum, 3, 1-23. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259000108

[26] Kavoura, A., & Ryba, T. V. (2020). Identity tensions in dual career: the discursive construction of future selves by female Finnish judo athletes. Sport in Society, 23(4), 645-659. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1669325

[27] Kristiansen, E., & Stensrud, T. (2017). Young female handball players and sport specialisation: how do they cope with the transition from primary school into a secondary sport school? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(1), 58-63. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096435

[28] Lee, D. (2012). Exploring Desirable Direction of School Athletic Teams as a Education Setting. Korean Society for the Study of Physical Education, 17(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2017-0123

[29] López de Subijana, C., Barriopedro, M., & Conde, E. (2015). Supporting dual career in Spain: Elite athletes’ barriers to study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 57-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.04.012

[30] Madsen, R. M., & McGarry, J. E. (2016). “Dads play basketball, moms go shopping!” social role theory and the preference for male coaches. Journal of Contemporary Athletics, 10(4), 277–291. www.researchgate.net/publication/312214368

[31] Martin, M., Soler, S., & Vilanova, A. (2017). Género y deporte. In M. García Ferrando, N. Puig Barata, & F. Lagardera Otero (Eds.), Sociología del deporte. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

[32] McGreary, M., Morris, R., & Eubank, M. (2021). Retrospective and concurrent perspectives of the transition into senior professional female football within the United Kingdom. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 53, 101855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101855

[33] Miró, S., Perez-Rivases, A., Ramis, Y., & Torregrossa, M. (2018). Compaginate or choosing? The transition from baccalaureate to university of high performance athletes. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 27(2), 59-68. https://archives.rpd-online.com/article/download/v27-n2-miro-perez-rivases-etal/1986-11547-2-PB.pdf

[34] Navarro, K. M. (2015). An Examination of the Alignment of Student-Athletes’ Undergraduate Major Choices and Career Field Aspirations in Life After Sports. Journal of College Student Development, 56(4), 364–379. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2015.0034

[35] Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuiness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting, P. & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

[36] Pankow, K., McHugh, T.-L. F., Mosewich, A. D., & Holt, N. L. (2021). Mental health protective factors among flourishing Canadian women university student-athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101847

[37] Park, S., Tod, D., & Lavallee, D. (2012). Exploring the retirement from sport decision-making process based on the transtheoretical model. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(4), 444-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.02.003

[38] Perez-Rivases, A., Pons, J., Regüela, S., Viladrich, C., Pallarès, S., & Torregrossa, M. (2020). Spanish female student-athletes’ perception of key competencies for successful dual career adjustment. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2020.1717575

[39] Perez-Rivases, A., Torregrosa, M., Pallarès, S., Viladrich, C., & Regüela, S. (2017a). Seguimiento de la transición a la universidad en mujeres deportistas de alto rendimiento. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 26, 102-107. https://archives.rpd-online.com/article/download/v26-n5-perez-rivases-torregrosa-etal/2332-10226-1-PB.pdf

[40] Perez-Rivases, A., Torregrosa, M., Viladrich, C., & Pallarès, S. (2017b). Women Occupying Management Positions in Top-Level Sport Organizations: A Self-Determination Perspective. Anales de Psicología, 33(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.1.235351

[41] Puig, N., & Soler, N. (2004). Women and sport in Spain: state of the matter and interpretative proposal. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 76, 71-78. https://revista-apunts.com/ca/dona-i-esport-a-espanyaestat-de-la-questio-i-propostainterpretativa/

[42] Ronkainen, N. J., Allen-Collinson, J., Aggerholm, K., & Ryba, T. V. (2020). Superwomen? Young sporting women, temporality and learning not to be perfect. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 00(0), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690220979710

[43] Ronkainen, N. J., Ryba, T. V., & Selänne, H. (2019). “She is where I’d want to be in my career”: Youth athletes’ role models and their implications for career and identity construction. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 45, 101562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101562

[44] Ronkainen, N., Watkins, I., & Ryba, T. (2016). What can gender tell us about the pre-retirement experiences of elite distance runners in Finland?: A thematic narrative analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 22, 37-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.06.003

[45] Rovira-Font, M., & Vilanova-Soler, A. (2022). LGTBIQA+, Mental Health and the Sporting Context: A Systematic Review. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 147, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2022/1).147.01

[46] Ryba, T. V., Stambulova, N. B., Ronkainen, N. J., Bundgaard, J., & Selänne, H. (2015). Dual career pathways of transnational athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 125-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.06.002

[47] Samuel, R. D., & Tenenbaum, G. (2011). How do athletes perceive and respond to change-events: An exploratory measurement tool. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12(4), 392-406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.03.002

[48] Selva, C., Pallarès, S., & González, M. D. (2013). Una mirada a la conciliación a través de las mujeres deportistas. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 22(1), 69-76. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=235127552010

[49] Shaw, R. (2010). Conducting Literature Reviews. In M. A. Fore (Ed.), Doing Qualitative Research in Psychology: A Practical Guide (pp. 39-52). London: Sage.

[50] Sherry, E., & Taylor, C. (2019). Professional women’s sport in Australia. In N. Lough & A. Geurin (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of the business of Women’s Sport (pp. 124-133). Milton Park, Oxon: Routledge.

[51] Skrubbeltrang, L. S. (2019). Marginalized gender, marginalized sports–an ethnographic study of SportsClass students’ future aspirations in elite sports. Sport in Society, 22(12), 1990-2005. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1545760

[52] Skrubbeltrang, L. S., Karen, D., Nielsen, J. C., & Olesen, J. S. (2020). Reproduction and opportunity: A study of dual career, aspirations and elite sports in Danish SportsClasses. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 55(1), 38-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690218789037

[53] Slaten, C. D., Ferguson, J. K., Hughes, H. A., & Scalise, D. A. (2020). ‘Some people treat you like an alien’: Understanding the female athlete experience of belonging on campus. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 37(1), 11-19. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2020.5

[54] Stambulova, N. B., & Alfermann, D. (2009). Putting culture into context: Cultural and cross ‐cultural perspectives in career development and transition research and practice. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7(3), 292-308. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2009.9671911

[55] Stambulova, N. B., Ryba, T. V., & Henriksen, K. (2021). Career development and transitions of athletes: the International Society of Sport Psychology Position Stand Revisited. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 19(4), 524-550. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2020.1737836

[56] Stambulova, N., Stephan, Y., & Jäphag, U. (2007). Athletic retirement: A cross-national comparison of elite French and Swedish athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 8(1), 101-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.05.002

[57] Stambulova, N., & Wylleman, P. (2015). Dual career development and transitions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.05.003

[58] Stambulova, N., & Wylleman, P. (2019). Psychology of athletes’ dual careers: A state-of-the-art critical review of the European discourse. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42(November 2018), 74-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.11.013

[59] Tekavc, J. (2017). Investigation into gender specific transitions and challenges faced by female elite athletes. Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

[60] Tekavc, J., Wylleman, P., & Cecić Erpič, S. (2020). Becoming a mother-athlete: female athletes’ transition to motherhood in Slovenia. Sport in Society, 23(4), 734-750. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1720200

[61] Tekavc, J., Wylleman, P., & Cecić, S. (2015). Perceptions of dual career development among elite level swimmers and basketball players. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 27-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.03.002

[62] Tod, D. (2019). Conducting Systematic Reviews in Sport, Exercise, and Physical Activity. In Springer Nature. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12263-8

[63] Tod, D., Booth, A., & Smith, B. (2021). Critical appraisal. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 0(0), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1952471

[64] Torregrossa, M., Chamorro, J. L., & Ramis, Y. (2016). Transición de júnior a sénior y promoción de carreras duales en el deporte: una revisión interpretativa. Revista de Psicología Aplicada al Deporte y el Ejercicio Físico, 1(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.5093/rpadef2016a6

[65] Torregrossa, M., Ramis, Y., Pallarés, S., Azócar, F., & Selva, C. (2015). Olympic athletes back to retirement: A qualitative longitudinal study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 50-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.03.003

[66] Torregrossa, M., Regüela, S., & Mateos, M. (2020). Career Assistance Programmes. In D. Hackfort & R. J. Schinke (Eds.), The Routledge international encyclopedia of sport and exercise psychology. (pp. 73-88). Oxon, New York: Routledge.

[67] Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., Godfrey, C.M, Macdonald, M.T., Langlois, E.V., Soares-Weiser, K., Moriarty, J., Clifford, T., Tunçalp, Ö. & Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467-473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

[68] Vilanova, A., & Puig, N. (2016). Personal strategies for managing a second career: The experiences of Spanish Olympians. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 51(5), 529-546. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690214536168

[69] Vilanova, A., & Soler, S. (2008). Women, Sport and Public Space: Absences and protagonisms. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 91, 29-3. https://revista-apunts.com/en/women-sport-and-public-space-absences-and-protagonisms/

[70] Williams, T. L., & Shaw, R. L. (2016). Synthesizing Qualitative Research. Meta-synthesis in sport and exercise. In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise (pp. 274-288). New York: Routledge.

[71] Wylleman, P. (2019). An organizational perspective on applied sport psychology in elite sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 89-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.01.008

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: September 2, 2022

Accepted: February 28, 2023

Published: October 1, 2023

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en