Differences in Court Shifts and Continuous Playing Time in Basketball

*Corresponding author: Franc García francgarciagarrido@gmail.com

Cite this article

García, F., Fernández, D., Pintado, C., Miró, A. y Lara-Bercial, S. (2025). Differences in court shifts and continuous playing time in basketball. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 161, 41-49. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2025/3).161.05

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the differences in the number of basketball court shifts and continuous playing time between age groups and game quarters during competition to optimize team preparation. Data from 28 official games was collected, which were completed in four different age groups: Under-14 (U14), Under-16 (U-16),Under-18 (U-18) and senior level. A total of 61 basketball players participated in this study. Permutation 2×2 ANOVA and post hoc tests were used to test statistical significance (p < .05). Age groups showed significant differences among court shifts, time, and their ratio (shifts·min-1), with a decreased tendency in all variables from U14 to senior level. Nevertheless, there were no significant differences in the variables studied among game quarters or positive relationships with the point differential. In conclusion, shifts·min-1 decreases as we progress through the age-groups from U14 to senior basketball. These results could help practitioners to enhance team’s preparation by proposing specific 5-on-5 training scenarios based on the most common occurrences as well as the outlying maximal situations. However, the lack of any correlation between the variables studied and game outcome should encourage basketball professionals to assume a holistic approach and explore additional factors to better understand performance.

Introduction

Basketball is one of the most popular team sports in the world. In Europe and the United States, high-level teams can complete up to 100 official games in an eight- to ten-month season (de Saá Guerra et al., 2016; Hulteen et al., 2017). Likewise, academy basketball teams (i.e., youth basketball performance) also tend to participate in regular leagues and congested tournaments where they are required to play multiple 5-on-5 games in a very short period (García et al., 2023a; Miró et al., 2024). Within these games, players engage in multiple bouts of successive and continuous court shifts (change of possession that results in the team regaining ball control crossing the half-way line) to achieve their ultimate goal to score points and not to concede them (Fox et al., 2020a). Therefore, a detailed analysis of the number of successive and continuous court shifts that basketball players must be able to withstand during games is critical to improve training drills and plans aiming to optimize team performance during competition (Piedra et al., 2021; Sampaio & Janeira, 2003).

Currently, most of the analysis during basketball games focuses on internal and external workload monitoring identified using technology such as heart-rate monitors (e.g., heart rate parameters), inertial devices (e.g., player load and accelerations) and local positioning systems (e.g., distance related variables) (Piedra et al., 2021; Zamora et al., 2021). For instance, it is well known that basketball players can cover between 130 and 150 m·min-1 of total distance and between 4 and 6 m·min-1 of high-speed running at average physiological intensities above 80% of maximal heart rate during games (García et al., 2022). More recently, external load has also been used to detect possible differences between game quarters (García et al., 2020; Miró et al., 2024; Vázquez-Guerrero et al., 2020a) and age groups (García et al., 2021) during basketball competition. Current research has shown multiple differences between quarters after examining averages and the most demanding scenarios among academy (Vázquez-Guerrero et al., 2019; Vázquez-Guerrero et al., 2020a), semi-professional (Fox et al., 2020b) and professional basketball players (García et al., 2020). Similarly, age groups such as Under-12, Under-14, Under-16, and Under-18 have also been analyzed using external load (García et al., 2021). While high-speed running distance increased with age, Under-12 showed the highest result in relative total distance covered and the lowest values in the 60-second most demanding scenarios of match play compared with their older counterparts (García et al., 2021; Pérez-Chao et al., 2023). Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that age groups in basketball have only been examined and compared using external load.

In addition to internal and external load variables, recent investigations in team-sports have proposed the inclusion of more qualitative variables to complement the lineal and quantitative perspective based on physical and physiological parameters (García et al., 2023b; Ortega Toro et al., 2006). Specifically, García et al. (2023b) used offensive tactical actions (e.g., different types of screens, hand-off, and cuts) to investigate the factors that influence effectiveness in basketball. Similarly, recent literature (Bazanov et al., 2005, 2006; Ortega Toro et al., 2006) has also examined basketball performance from a more ecological nature and has included the concept of game rhythm, understood as the sum of technical and tactical actions divided by time.

Similarly, previous research in basketball has also studied the number and duration of ball possessions (defined as the period of time when a team has clear control of the ball) to compare different scenarios (Salazar & Castellano Paulis, 2020; Sampaio & Janeira, 2003). In addition to being useful for comparing gender and playing levels (Romarís et al., 2016), ball possessions, calculated with indirect equations using common game-related statistics such as field goals, rebounds, turnovers and free throws (Oliver, D., 2004; Kubatko et al., 2007), have also been utilized to understand the crucial factors of successful teams. The conclusions of such studies are that playing faster-paced attacks (i.e., shorter and a higher number of ball possessions) tends to elicit higher scores per games in basketball (Bazanov et al., 2005; Sampaio et al., 2010). Although recent literature has used ball possessions, and technical and tactical basketball actions to investigate possible differences between winning and losing teams (Bazanov et al., 2005, 2006; Ortega Toro et al., 2006), to date no research has investigated the total number of court shifts in basketball and their distribution in bouts of continuous playing time (understood as game periods without interruptions and game stoppages) in different age groups during basketball games.

Therefore, the principal aim of this study was to examine the differences in the number of court shifts accumulated during continuous basketball playing time among age groups and game quarters to optimize specific training drills and game preparation. A secondary objective was to detect possible relationships between basketball court shifts, continuous playing time, and shifts·min-1 with the final score of the games examined. Our main hypothesis was that there would be significant differences between age groups and no relationships between the variables studied and the outcome of the game.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The participants in this study were male basketball players (mean ± SD, age: 14.5 ± 1.7 years; body height: 186.3 ± 13.0 cm; body mass: 72.0 ± 13.9 kg and wingspan: 188.4 ± 13.0), within the elite basketball academy of a Euroleague team. Players competed in four age groups: Under-14 (U14), Under-16 (U16), Under-18 (U18), and a senior team (Table 1). U14 and U16 teams competed at the highest possible regional level, whereas the U18 competed in both competitions: its regional league and the fourth Spanish semi-professional league (EBA). All games were based on FIBA rules. Furthermore, all teams followed the specific structured training methodology (Tarragó et al., 2019), consisting of coadjuvant and optimising training (Gómez et al., 2019; Pons et al., 2020).

This study was performed in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki (Harriss & Atkinson, 2015), and no ethics committee approval was required as the data were obtained routinely during player league games (Winter & Maughan, 2009). Notwithstanding the above, players and their parents provided their written consent after the purpose of the investigation and the research protocol along with requirements had been explained to them.

Methodology

A descriptive and observational design was used to examine the differences between court shifts, continuous playing time, and shifts·min-1, between age groups and game quarters. Data was collected from 28 league home games (7 U14 games; 4 U16 games; 8 U18 games; 8 senior EBA games) during the 2022-2023 Spanish competitive basketball season (September-June). The final sample had a total of 2087 observations. Besides, it is important to consider that data was recorded under different conditions for each group, such as the competitive context, the tactical requirements and the variation of individual roles. While some players may be present in more than one team, the time gap between measurements could limit the influence of the same experimental unit across age groups.

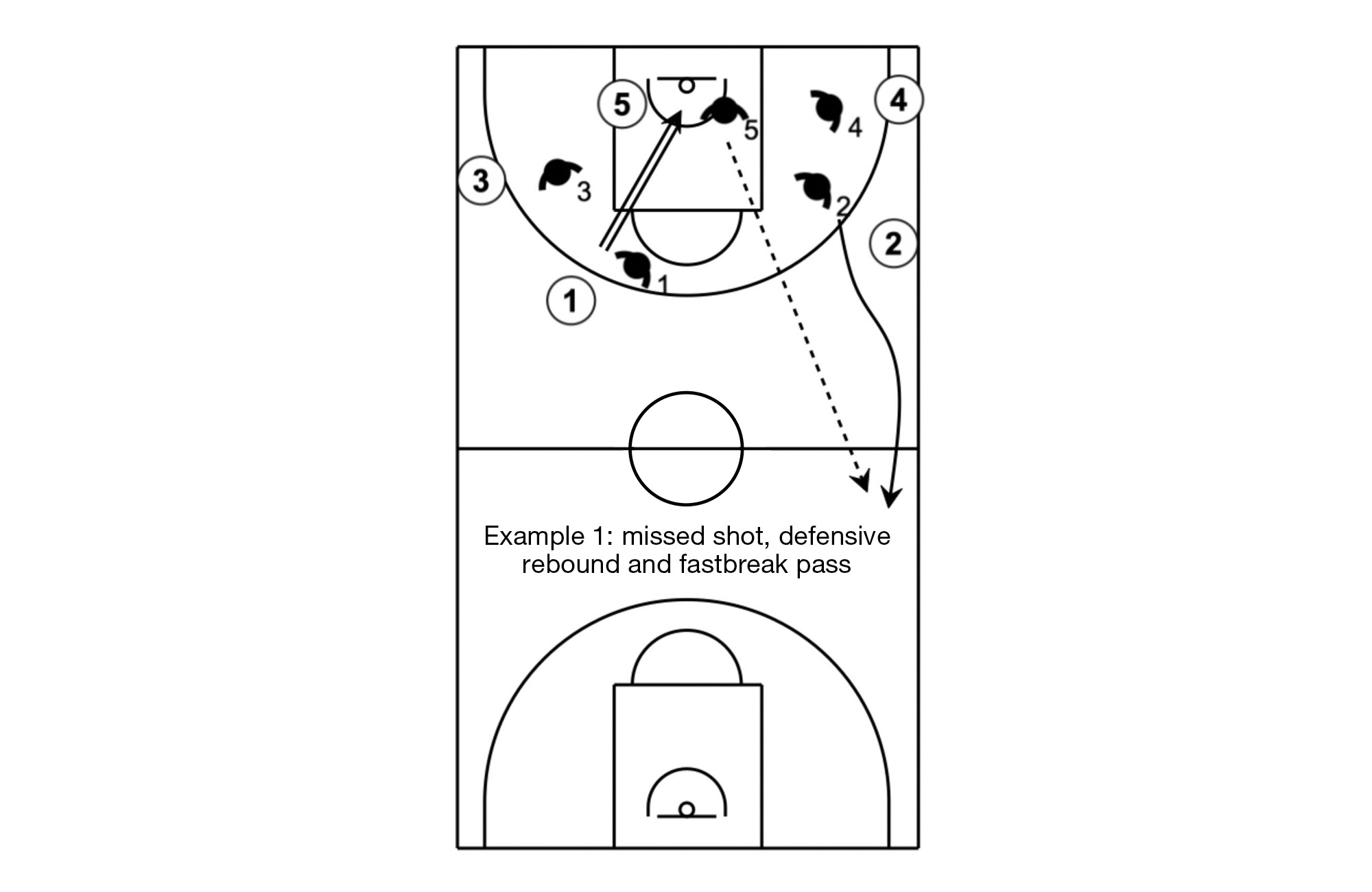

The measurement of court shift (Figure 1) was inspired by our experience of basketball coaches planning their training on sets of 5-on-5 playing half court plus one or two transitions, which have been renamed in this study as 1.5 or 2.5 shifts, respectively.Court shifts and continuous playing time were collected manually during games. Furthermore, the ratio between basketball court shifts and continuous playing time was calculated and normalized to a minute, being thus: shifts per minute (shifts·min-1). A stopwatch was used to calculate the time of live continuous play. Furthermore, all game analysis was completed by the same professional, who is an experienced researcher and holds the highest basketball coaching qualification in the Spanish system (i.e., national coach, level 3).

Statistical Analysis

All the statistical analyses were conducted with RStudio version 2022.07.2 (RStudio, Inc.). Descriptive results were reported as mean ± standard deviation. For more information and due the skewness, we also used the mode and maximum values. All the variables failed all the tests for homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test) and normality (Shapiro–Wilk test). Due to this kind of data distribution, a 2 × 2 permutation ANOVA with a maximum of 5000 iterations (Venables, W.N., & Ripley, B.D., 1997), was conducted to identify significant differences in all the studied variables. The two independent variables used in the 2 × 2 model were the age group that players belonged to, and the game quarter. All reported p-values were the likelihoods of the absolute effect sizes being observed if the null hypothesis of zero difference was true (Plonsky, 2015). Furthermore, we added the eta-squared value (η2) to describe the effect size; where according to Cohen (Cohen, 1988), the magnitude was considered negligible (η2 < .01), small (.01 < η2 < .06), medium (.06 < η2 < .14), large (η2 > .14). Tukey HSD post hoc tests were conducted after the ANOVA between each pairwise comparison. A bootstrapped correlation analysis with 2000 repetitions (Wilcox, 2010) was conducted between the mean match studied variable and difference of points at the end of the match by age group; and bias-corrected and accelerated method was used to found the 95% confidence intervals of the correlation analysis. The magnitude of correlation coefficients, according to Hopkins (Hopkins, 2006), was considered trivial (r < .1), small (.1 < r < .3), moderate (.3 < r < .5), large (.5 < r < .7), very large (.7 < r < .9), almost perfect (r > .9), or perfect (r = 1).

Results

The descriptive results grouped by age group and by quarter are presented in Table 2 and Table 3. Furthermore, the descriptive results of all the variables and the results from the 2 × 2 permutation ANOVA are presented in Table 4, and the visual representation of the results and the post hoc analysis in Figure 2.

Significant differences were only found between age groups in the three studied variables (Playing time: F Iterations = 5000, p < .001, η2 = .02; Number of basketball court shifts: F Iterations = 5000, p < .001, η2 = .02; Shifts·min-1: F Iterations = 5000, p < .001, η2 < .001). In the three variables, the effect size of the difference was small and even in shifts·min-1, the effect size was negligible. Finally, the mode and maximum values are presented in Table 5.

The results of correlations grouped by age group are presented in Figure 3. Although some moderate correlations were found between variables and the result of the match, none of them were significant.

Discussion

The present descriptive study aimed to compare the number of court shifts in basketball during continuous playing time between age groups and game quarters; and examine its relationship with the final score. The primary finding is that the number of court shifts, playing time, and shifts·min-1 showed significant differences between age groups. Nevertheless, there were no significant differences in the variables studied among game quarters. Furthermore, none of the variables studied presented a meaningful relationship with the final score, examined as the difference in points between the studied team and the opposition. Although the lack of significant correlation between a specific shifts·min-1 and success during basketball competition, these results could help to optimize the prescription of specific 5-on-5 training situations adapted to each specific age level.

Regarding the differences between age groups in the number of court shifts, playing time, and shifts·min-1, our results align with previous research (García et al., 2021), showing a downwards trend between age and external load variables. While García et al. (2021) found that total distance covered was significantly higher in the U12 (87.1 m·min-1) team compared to their older counterparts (U14 to senior: 73.9-82.5 m·min-1) and that senior players presented significantly lower results than in the other four youth teams assessed in the same variable, the current study also showed that shifts·min-1 decreased from U14 to U16, slightly increased from U16 to U18 and decreased again from U18 to seniors. It is worth noting that the U18 and senior competition was played by the same U18 group of players, which demonstrates the importance of the context to explain basketball game rhythm. Specifically, the number of court shifts, playing time, and shifts·min-1 presented significant differences (p < .001) and small effect sizes (ES = 0.2) between age groups. Additionally, the maximum value of basketball court shifts (n = 15) and the highest shift-min-1 (n = 22) was also found in the U14 age level (Table 5). A possible explanation could be that more experienced basketball players possess better game interpretation and decision-making skills leading to enhanced game management and decreased values in physical demands (Ferioli et al., 2020).

Although results in basketball court shifts, time and shifts·min-1 were significantly different between basketball players from U14, U16, U18 and senior level, the current investigation did not detect meaningful variations between game quarters. Similarly, recent literature (Scanlan et al., 2012, 2015) could not report differences by quarter after the analysis of distance and speed parameters in senior players. Despite the lack of significance, the present research suggests a decrease in the number of basketball court shifts and continuous playing time in all age groups as the game progresses, showing the lowest values in the second half (Table 3). In this regard, the mode value –defined as the most frequently occurring value– of court shifts and continuous playing time was found in the last quarter of the game across all age groups (Table 5). By contrast, our data shows an upwards trend in shifts·min-1 during the game. This increase could be attributed to the higher number of game stoppages present during the fourth quarter which may allow players more recovery time and thus the capacity to perform at a higher tempo (Salazar & Castellano Paulis, 2020).

Similar to the differences between quarters, the point differential between the examined team and its opponent was not significantly related to the three variables studied. Nevertheless, the current research found interesting the moderate to very large non-significant correlations between some variables and point differential, which could imply that each age group has its optimal game rhythm. This finding could imply that there was no significant relationship between shifts·min-1 of the analyzed team and success in basketball. Similarly, current literature (Fox et al., 2020c; García et al., 2022; Vázquez-Guerrero et al., 2020b) also failed to find a positive relationship between training loads and game performance in basketball through the use of external and internal loads during training competition. To be more specific, professional basketball players presented trivial relationships between external (e.g., high-speed running and high-intensity accelerations and decelerations) and internal (e.g., hear rate average) load variables, and game-related statistics (García et al., 2022). Overall, the lack of relationship between court shifts and playing time, and physical and physiological variables, with a higher win-loss ratio could lead basketball professionals to explore different contextual factors that affect and determine performance.

It is necessary to take some limitations into account. Despite assuming independence, there may still be some residual dependence between age groups, which could have an impact on the present results. Furthermore, the results from correlations should be interpreted with caution, as they may be influenced by data dependency, sampling variability and the small sample size. Regarding significance, this study has confirmed the presence of some statistically significant differences in the results. However, these differences exhibit a small and/or negligible effect size, which needs careful consideration when interpreting the current findings. In addition to the effect size, another potential limitation could be the fact that all teams monitored belonged to the same club and played under the same basketball philosophy. Thus, caution should be applied when generalizing these results. Besides, only 4 games of the U16 age group were examined. Future research should examine a wider variety of basketball teams with different styles and competition. In addition to continuous playing time, no resting time was measured. This would allow practitioners to better understand basketball density (total amount of volume accomplished in a specific amount of time) and prescribe optimal work-to-rest ratios to enhance player’s preparation. Furthermore, data was only collected during basketball games. Therefore, it would be recommended to also examine specific 5-on-5 training drills to evaluate the objectives proposed before the session.

Conclusion

This study showed multiple significant differences between basketball age groups in the number of continuous court shifts, playing time and shifts·min-1. In contrast, the variables examined failed to present significant differences between game quarters and no positive relationship with game success was found. These conclusions demonstrate the importance of assessing basketball performance from a holistic perspective which considers multiple types of variables to better understand the critical success factors during basketball competition. However, basketball coaches can use this information to enhance team training and preparation to optimize team performance during competition.

From a practical point of view, basketball coaches could:

- Base most of the full court 5-on-5 training exercises on sub-30 second periods.

- Choose to plan their training on a mix of half court and a maximum of 2 continuous possessions (i.e., back and forth).

- Include some scenarios of between 30 seconds and 2 minutes and at least one long scenario of approximately 3 minutes and up to 15 continuous court shifts to ensure that players are prepared for a rare but possible extreme game situation.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of a Spanish government Project entitled Optimisation of the preparation process and competitive performance in Team Sports based on multi-modal and multi-level data integration by intelligent models [PID2023-147577NB-I00] for the four years 2024-2027, in the 2023 call for grants for «KNOWLEDGE GENERATION PROJECTS», in the framework of the State Program to Promote Scientific-Technical Research and its Transfer, of the State Plan for Scientific, Technical and Innovation Research of the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (MCIU).

References

[1] Bazanov, B., Haljand, R., & Võhandu, P. (2005). Offensive teamwork intensity as a factor influencing the result in basketball. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 5(2), 9–16. doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2005.11868323

[2] Bazanov, B., Võhandu, P., & Haljand, R. (2006). Factors influencing the teamwork intensity in basketball. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 6(2), 88–96. doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2006.11868375

[3] de Saá Guerra, Y., Martín González, J. M., García Manso, J. M., & García Rodríguez, A. (2016). Agrupación y equilibrio competitivo en el baloncesto profesional NBA y ACB. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 124, 07–26. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2016/2).124.01

[4] Ferioli, D., Rampinini, E., Martin, M., Rucco, D., la Torre, A., Petway, A., & Scanlan, A. (2020). Influence of ball possession and playing position on the physical demands encountered during professional basketball games. Biology of Sport, 37(3), 269–276. doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2020.95638

[5] Fox, J. L., O’Grady, C. J., & Scanlan, A. T. (2020a). Game schedule congestion affects weekly workloads but not individual game demands in semi-professional basketball. Biology of Sport, 37(1), 59–67. doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2020.91499

[6] Fox, J. L., Salazar, H., García, F., & Scanlan, A. T. (2020b). Peak external intensity decreases across quarters during basketball games. Montenegrin Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 8(2), 5–12. doi.org/10.26773/mjssm.210304

[7] Fox, J. L., Stanton, R., J. O’Grady, C., Teramoto, M., Sargent, C., & T. Scanlan, A. (2020c). Are acute player workloads associated with in-game performance in basketball? Biology of Sport, 39(1), 95–100. doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2021.102805

[8] García, F., Castellano, J., Reche, X., & Vázquez-Guerrero, J. (2021). Average game physical demands and the most demanding scenarios of basketball competition in various age groups. Journal of Human Kinetics, 79(1), 165–174. doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2021-0070

[9] García, F., Castellano, J, Vicens-Brodas, J., Vázquez-Guerrero, J., & Ferioli, D. (2023a). Impact of a six-day official tournament on physical demands, perceptual-physiological responses, well-being, and game performance of U-18 basketball players. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2022-0460

[10] García, F., Fernández, D., & Martín, L. (2022). Relationship between game load and player’s performance in professional basketball. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 1–8. doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2021-0511

[11] García, F., Fernández, D., Uckan, A., Vázquez-Guerrero, J., & Pla, F. (2023b). Does high tactical game rhythm present better effectiveness in basketball ? Sport Performance & Science Reports, 1.

[12] García, F., Vázquez-Guerrero, J., Castellano, J., Casals, M., & Schelling, X. (2020). Differences in physical demands between game quarters and playing positions on professional basketball players during official competition. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 19(2), 256–263.

[13] Gómez, A., Roqueta, E., Tarragó, J. R., Seirul·lo, F., & Cos, F. (2019). Training in team sports: coadjuvant training in the FCB. Apunts. Educació Física i Esports, 138, 13–25. doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.cat.(2019/3).137.08

[14] Hopkins, W. G. (2006). A scale of magnitudes for effect statistics. SportSci. www.sportsci.org/resource/stats/index.html%0A

[15] Hulteen, R. M., Smith, J. J., Morgan, P. J., Barnett, L. M., Hallal, P. C., Colyvas, K., & Lubans, D. R. (2017). Global participation in sport and leisure-time physical activities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Preventive Medicine, 95(2), 14–25. doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.11.027

[16] Kubatko, J., Oliver, D., Pelton, K., & Rosenbaum, D. T. (2007). A starting point for analyzing basketball statistics. Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports, 3(3). doi.org/10.2202/1559-0410.1070

[17] Miró, A., Vicens-bordas, J., Beato, M., Salazar, H., Coma, J., & Pintado, C. (2024). Differences in physical demands and player’s individual performance between winning and losing quarters on U-18 basketball players during competition. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 1–9.

[18] Oliver, D. (2004). Basketball on paper. Rules and tools for performance analysis. Brassey´s Inc.

[19] Ortega, E., Cárdenas, D., Sainz de Baranda, P., & Palao, J. (2006). Differences between winning and losing teams in youth basketball games (14-16 years old). International Journal of Applied Sports Sciences, 18(2), 14.

[20] Pérez-Chao, E. A., Portes, R., Gómez, M. Á., Parmar, N., Lorenzo, A., & Jiménez-Sáiz, S. L. (2023). A Narrative Review of the Most Demanding Scenarios in Basketball: Current Trends and Future Directions. Journal of Human Kinetics , 89(October), 231–245. doi.org/10.5114/jhk/170838

[21] Piedra, A., Peña, J., & Caparrós, T. (2021). Monitoring training loads in basketball: a narrative review and practical guide for coaches and practitioners. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 43(5), 12–35. doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0000000000000620

[22] Plonsky, L. (2015). Advancing quantitative methods in second language research (U. K. Routledge. (ed.); (1st ed.)).

[23] Pons, E., Martín-García, A., Guitart, M., Guerrero, I., Tarragó, J. R., Seirul·lo, F., & Cos, F. (2020). Training in team sports: optimiser training in the FCB. Apunts, Educació Física i Esports, October, 55–66. doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2020/4).142.07

[24] Romarís, I. U., Refoyo, I., & Lorenzo, J. (2016). Comparison of the game rhythm in Spanish Female League and ACB League. Cuadernos de Psicologia Del Deporte, 16(2), 161–168. www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85010754425&partnerID=40&md5=1f79828e33d274d91679e888a2298b08

[25] Salazar, H., & Castellano Paulis, J. (2020). Analysis of basketball game: Relationship between live actions and stoppages in different levels of competition. E-BALONMANO COM, 16(2), 109–118.

[26] Sampaio, J., & Janeira, M. (2003). Statistical analyses of basketball team performance: understanding teams ’ wins and losses according to a different index of ball possessions. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 3(1), 40–49. doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2003.11868273

[27] Sampaio, J., Lago, C., & Drinkwater, E. (2010). Explanations for the United States of Americas dominance in basketball at the Beijing Olympic. Journal of Sports Sciences, 28(2), 147–152. doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410903380486

[28] Scanlan, A. T., Dascombe, B. J., Reaburn, P., & Dalbo, V. J. (2012). The physiological and activity demands experienced by Australian female basketball players during competition. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 15(4), 341–347. doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2011.12.008

[29] Scanlan, A. T., Tucker, P. S., Dascombe, B. J., & Berkelmans, D. M. (2015). Fluctuations in activity demands across game quarters in professional and semiprofessional male basketball. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 29(11), 3006–3015. doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000967

[30] Tarragó, J. R., Massafret-Marimón, M., Seirul·lo, F., & Cos, F. (2019). Training in team sports: structured training in the FCB. Apunts, Educació Física i Esports, 137(3), 103–114. doi.org/https://dx.doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2019/3).137.08

[31] Vázquez-Guerrero, J., Ayala Rodríguez, F., García, F., & Sampaio, J. E. (2020a). The most demanding scenarios of play in basketball competition from elite Under-18 teams. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 552. doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00552

[32] Vázquez-Guerrero, J., Casals, M., Corral-López, J., & Sampaio, J. (2020b). Higher training workloads do not correspond to the best performances of elite basketball players. Research in Sports Medicine, 00(00), 1–13. doi.org/10.1080/15438627.2020.1795662

[33] Vázquez-Guerrero, J., Fernández-Valdés, B., Jones, B., Moras, G., Reche, X., & Sampaio, J. (2019). Changes in physical demands between game quarters of U18 elite official basketball games. Plos One, 14(9), 1–14. doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221818

[34] Zamora, V., Capdevila, L., Lalanza, J. F., & Caparrós, T. (2021). Heart rate variability and accelerometry: Workload control management in Men’s basketball. Apunts. Educacion Fisica y Deportes, 143, 44–51.doi.org/10.5672/APUNTS.2014-0983.ES.(2021/1).143.06

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: July 18, 2024

Accepted: February 25, 2025

Published: July 1, 2025

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en