Coaches’ Career Adaptability: Effects on their Mental Health and Support for their Athletes

*Corresponding author: Maria Cosin Miguel maria.cosin@autonoma.cat

Cite this article

Cosin-Miguel, M., Ramis, Y. & Alcaraz, S. (2025). Coaches’ Career Adaptability: Effects on their mental health and support for their athletes. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 161, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2025/3).161.01

Abstract

The aim of this work was to assess the effects of coaches’ career adaptability competencies related to their mental health and their perception of providing support to their athletes. Two hundred and seventy-five training coaches answered the questionnaires on the target variables: Career adaptability, Mental Health and Athlete Career Support competencies. Our results partially supported the hypothesised structural equation model in which adaptability competencies were expected to predict both coaches’ mental health and the perception of support offered to their athletes. Specifically, the control competence was predictive of mental health, whilst concern and confidence competencies were predictive of athlete support. The findings indicate that the development of the control competency is significantly predictive of coaches’ mental health, while the development of the confidence and concern competencies are positively related to the perception that they provide greater support to their athletes. Therefore, enhancing these competencies of coaches, with a special focus on control and confidence, seems to be beneficial for both coaches and athletes.

Introduction

Many coaches put their efforts, resources and dedication throughout their careers into achieving a professional and exclusive dedication (Rynne, 2014). In the Spanish context, the most common profile of coaches is characterised by having specialised sports training, university education and a high vocation for coaching (Ibáñez et al., 2019; Feu et al., 2018). However, in the early stages of the career, being a coach involves working on a voluntary or temporary contract basis, precarious working conditions and generally low or no financial remuneration (Ronkainen et al., 2020). This implies looking for alternative jobs as the main source of income and makes it essential to have a flexible and adaptive attitude, by developing personal resources that allow coaches to balance the different spheres of life (Cosín-Miguel et al., 2023).

Within the general coaching community, McLean and Mallett (2012) proposed a classification based on competitive level (i.e., participation, development and high performance). In the Spanish context, the developmental coach profile refers to the so-called training coaches, who regularly train athletes in the sport development stage, and participate in regulated competitions within performance-oriented environments (Alcaraz et al., 2015). In this context, the concept of career adaptability (hereafter CA) becomes particularly relevant, especially considering the dedication to semi-professional training and management. CA has been defined as “the readiness to cope with predictable tasks in preparation for and participation in the job role, and with unpredictable adjustments brought about by changes in work and working conditions” (Savickas, 1997). Based on this definition, Savickas and Porfeli (2012) developed a specific theory of career adaptability, which comprises four core competencies: (a) the level of proactivity in preparing for the future (i.e.,, concern), (b) the ability to self-regulate and adapt to the environment when facing challenging situations (i.e.,, control), (c) the tendency to explore the context in search of new information and opportunities (i.e.,, curiosity), and (d) the capacity for self-confidence, overcoming obstacles (i.e.,, confidence).

Some authors show that developing career adaptability competencies (hereafter, CACs) favours adaptation to transitions and trajectories, personal functioning and life satisfaction in different contexts: (a) general population (Maggiori et al., 2015); (b) work contexts with employed and unemployed people (Maggiori et al., 2013); (c) academic contexts with students (Negru-Subtirica et al., 2015); and (d) sport contexts with student-athletes (Ojala et al., 2023). On a more specific level, some studies in Johnston’s (2016) systematic review highlighted the specific effects of each dimension on some target variables. For example, concern and confidence competencies were related to self-assessed performance (Zacher, 2014). Also, control competence is positively associated with life satisfaction (Konstam et al., 2015). In turn, control and confidence competencies relate to career and organisational continuity (Omar & Noordin, 2013). In addition, curiosity competence favours proactive networking (Taber & Blankemeyer, 2015).Overall, these results indicate that the four dimensions complement each other, and that improvement in each dimension separately can have different effects on aspects such as career development (Omar & Noordin, 2013), mental health and general well-being (Maggiori et al., 2013).

The present study focuses precisely on examining the influence of CA on the mental health of coaches, according to the model proposed by Keyes (2002). This model views mental health as a dual continuum that considers both the presence/absence of mental illness and the presence/absence of mental health. That is, the dimensions of health and mental illness are independent but complementary, emphasising that the absence of mental illness does not necessarily mean optimal mental health, but rather the cognitive and social functioning of the individual in his or her various roles. Considering previous research in the field of sport psychology based on this model, it is suggested that the level of functioning and well-being of individuals can be analysed independently (e.g., Schinke et al., 2018). As our perspective does not follow a clinical approach, the present research focused exclusively on the mental health dimension. This highlights the importance of considering both adaptive mental health, which reflects aspects of well-being, and maladaptive mental health, which reflects aspects of distress (Keyes, 2002). In this vein, previous studies have shown that CACs act as a protective factor for mental health, proving that the control competence is directly related to job stability (Maggiori et al., 2013), and that it can also increase levels of subjective happiness and reduce work-related stress (Johnston et al., 2013). In addition, concern and confidence CACs have been related to career satisfaction (Zacher, 2014), while in students, curiosity and confidence CACs have been found to mediate between hope and satisfaction (Wilkins et al., 2014).

This background, coupled with the fact that coaches are a population exposed to a combination of high external expectations, high levels of exposure, limited job control and long working hours (Chroni et al., 2024), makes it of particular interest to analyse the relationship between their CACs and their mental health. However, the only study found that has explored these competencies in coaches is the qualitative work of Ronkainen et al. (2020) in elite women’s football. The study concluded that competencies of control and confidence promote adaptability, while low levels of concern and curiosity leave coaches vulnerable to psychological distress. This lack of evidence suggests the need for further research on the career development of coaches to understand their adaptability dynamics and its influence on their mental health. In this sense, a coach with difficulties in planning (concern), self-regulation (control), seeking alternatives (curiosity), and self-assurance (confidence) may have low levels of mental health (Maggiori et al., 2013). These difficulties in CA could affect coaches both intrapersonally and interpersonally (Savickas & Porfeli, 2012).

Nonetheless, beyond the mental health consequences, CA enables people to self-manage their personal aspects and responses to their environment and fosters empathy and social connectedness (Savickas, 1997; e.g., with athletes). In this context, coaches have a responsibility to contribute to the holistic development of their athletes by providing support in both sport and non-sport areas (Chroni et al., 2024). In addition, skills included within the CACs in the concern dimension, such as proactivity and planning for the well-being of the athlete, have been related to an increased willingness to provide emotional support (Teck Koh et al., 2019). Similarly, the control competence is positively associated with positive affect, and negatively associated with negative affect (Konstam et al., 2015). Curiosity and concern CACs have been linked to aspects of personality (e.g., openness to experience, kindness, conscientiousness and behavioural arousal system; Li et al., 2015). Finally, the confidence competence supports proactive skill development (e.g., listening, offering constructive criticism; Taber & Blankemeyer, 2015). This suggests that strengthening CACs could improve the support that coaches offer to their athletes. Supportive behaviours include (Cutrona & Russell, 1990; Freeman et al., 2011): (a) emotional support, which incorporates comfort, security; (b) esteem support, which includes reinforcement of self-esteem and sense of competence; (c) informational support, which incorporates counselling; and (d) tangible support, which provides practical assistance. However, the study of coaches’ development of CACs and its influence on their support for their athletes remains an undiscovered area of research. For example, research on the relationship between CA and student-athlete trajectories has concluded that the development of CACs must be approached from a holistic perspective, considering not only the student-athlete, but also the active role of their environment and their constituents (e.g., coaches; Ojala et al., 2023).

In short, we believe that CACs could safeguard their own mental health and improve support for their athletes. In that sense, planning (concern), goal selection (control), exploration of the sport context (curiosity) and self-confidence (confidence) could also be associated with coaches’ mental health and the support they provide to their athletes, as these competencies are signs of adaptability in their career.

Although CACs have been studied in the domain of work (Maggiori et al., 2013) and sports in general (Ojala et al., 2023), there is still a need for further research on the influence of each of the four competencies separately in the context of the coach (Ojala et al., 2023; Ronkainen et al., 2020). Moreover, we see value in assessing the relationship of CACs to mental health and the support provided. Therefore, this paper aims to address this issue by studying the effects of these competencies separately, specifically on training coaches. It assesses the effects of coaches’ CACs (a) on their mental health, and (b) on their perception of the support they provide to their athletes. Our model hypothesises that better career adjustment is related to better mental health, and better perceived support for their athletes.

Method

Participants

This study was designed as part of the HeDuCa project (RTI2018-095468-B-100), aimed at assessing the contextual characteristics of young athletes developing their careers in performance environments. Coaches were contacted through their clubs or institutions using convenience sampling. A total of 275 training coaches (231 males, 38 females and 6 of non-binary gender) aged between 16 and 62 years (M = 34.57 years; SD = 10.46) participated in the study. This distribution is consistent with the gender and age distribution of this coaching population in Spain (Ministry of Culture and Sports, 2024). Half of the participants (50.5%) had between 0 and 10 years of coaching experience. Detailed characteristics of the coaches grouped by sport can be found in Table 1. The group “Others” includes those sports with less than 5 participants. Furthermore, 65.5% of the coaches were working at regional level, both in men’s and women’s teams. In terms of career balance, 23.6% were active athletes as well as coaches; 27.3% were students; 55.3% had other jobs in addition to coaching, and 6.2% had no other job but were looking for one. Finally, regarding their coaching contracts, 19.3% had no coaching contract, 29% had a volunteer agreement, 27.6% had a part-time contract and 24% had a full-time contract.

Table 1

Characteristics of participants according to sport, gender and training experience

Instruments

Career adaptability competencies. We used the questionnaire Career Adapt-Abilities Scale(CAAS; Savickas & Porfeli, 2012) to assess the coach’s perception of the degree of readiness in each of the CACs. This instrument contains 24 items grouped into four dimensions beginning with the phrase “In my coaching career…”: (a) concern (e.g., “… I think about what my future will be like”); (b) control (e.g., “… I make decisions for myself”); (c) curiosity (e.g., “… I look at different ways of doing things”); and (d) confidence (e.g., “… I work to the best of my ability”). Responses are presented on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). Higher scores indicate higher perceived levels of the CAC construct.

Mental health.The mental health assessment of the coaches considered both adaptive and maladaptive mental health with two scales starting with the clause “In recent weeks, in relation to sport, work and/or studies…”. We used six items from the scale The 12-item General Health Questionnaire(GHQ-12; Sánchez-López & Dresch, 2008) to measure maladaptive mental health (e.g., “… I have lost self-confidence”), and the remaining six items were used to measure adaptive mental health (e.g., “… I have coped well with problems”). In addition, we supplemented the measurement of adaptive mental health with the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWB; Shah et al., 2021) (e.g., “… I felt close to other people”). This instrument contains seven items, we removed three items assessing adaptive mental health, as they were partially duplicated with those of the GHQ-12. We presented the responses on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). Higher scores imply a higher perception by coaches of their adaptive or maladaptive mental health.

Career support for the athlete. We used the Perceived Available Support in Sport Questionnaire (PASS-Q; Freeman et al., 2011) to assess the general perception of the support offered to athletes’ careers, in its version for coaches. This instrument contains 16 items grouped into four dimensions, but in this study, we grouped the items into a single dimension of general support, starting with the clause “In your relationship with the athletes you train, both on and off the court/playing field/pool, you…”: (e.g., “… improve their self-esteem”). We presented responses to the items using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). Higher scores indicate higher levels of the coach’s perception of his or her support for the athletes’ careers.

Procedure

The HeDuCa project (RTI2018-095468-B-100) establishes a data collection protocol that was validated by the Ethics Committee of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (CEEAH 5180). Once approval has been received, we initiated contact with the coordinators responsible for each club or sports entity. We got in touch with all the participants through these contacts. We informed them of the purpose of the study and guaranteed the confidentiality of their data. After informing them of the voluntary nature of the study, the coaches who agreed to participate signed an online informed consent form. For the data collection sessions, we agreed on the dates and procedure with the clubs. We explained to the coaches how to answer the questionnaire, using the online survey platform Limesurvey with their own mobile phones. In order to avoid gender bias, the questionnaires were designed in three versions with items written in female, male and non-binary gender. We carried out the data collection sessions either in person in the clubs or sports organisations before the start of the training sessions, or virtually. In both modalities, we had a protocol for data collection and channels in order to answer any questions raised by the participants. Coaches could ask questions if they did not understand any of the items correctly (face-to-face, by phone or by video call). Once their questions had been answered, they were asked if they had sent in their own answers. After completing the administration, the coaches returned to their regular routines.

Statistical Analysis

We structured the data analysis in three steps: (a) providing evidence of the psychometric properties of the instruments, (b) calculating descriptive statistics and correlations of the different study variables, and (c) analysing hypothesised relationships using structural equation modelling. First, we analysed the validity of the internal structure using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Through this analysis, conducted with the Mplus version 7.0 software (Muthén, 2012), we analysed the item scores as categorical using the Weighted Least Squares Robust Estimator (WLSMV), thus obtaining the estimation of a single measurement model that included all the latent factors estimated in the study. We measured the adjustment on the basis of the χ2 indices, root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis fit index (TLI). Based on Hu and Bentler’s criteria (Hu & Bentler, 1999), CFI and TLI indices > .95 and RMSEA < .06 are indicative of an excellent fit to the data. Moreover, CFI and TLI indices > .90 and RMSEA < .08 are indicators of acceptable fit (Marsh et al., 2004). To provide further evidence on the measurement models, we also analysed construct reliability (CR). Values > .70 are indicators of good reliability (McDonald, 1999). In addition, we obtained evidence of convergent validity after inspection of the factor loadings (Cheung et al., 2023). According to Hair et al. (2009), standardised factor loadings should be at least .5, and ideally ≥ .7. Furthermore, CR values above .7 are also indicative of convergent validity (Hair et al., 2009). Finally, we assessed discriminant validity by analysing (a) evidence of established convergent validity, (b) the absence of cross-loadings of indicators on other constructs, and (c) correlation between constructs (Cheung et al., 2023).

Subsequently, we analysed the descriptive statistics for each of the study variables based on means and standard deviations using the SPSS v25.0 package. In the same vein, we calculated the correlations between the study variables with Mplus version 7.0. (Muthén, 2012). For the interpretation of attenuated correlations between latent factors, the Safrit and Wood (1995) criteria were followed: .00-.19, no correlation; .20-.39, low correlation; .40-.59, moderate correlation; .60-.79, moderately high correlation; ≥.80, high correlation.

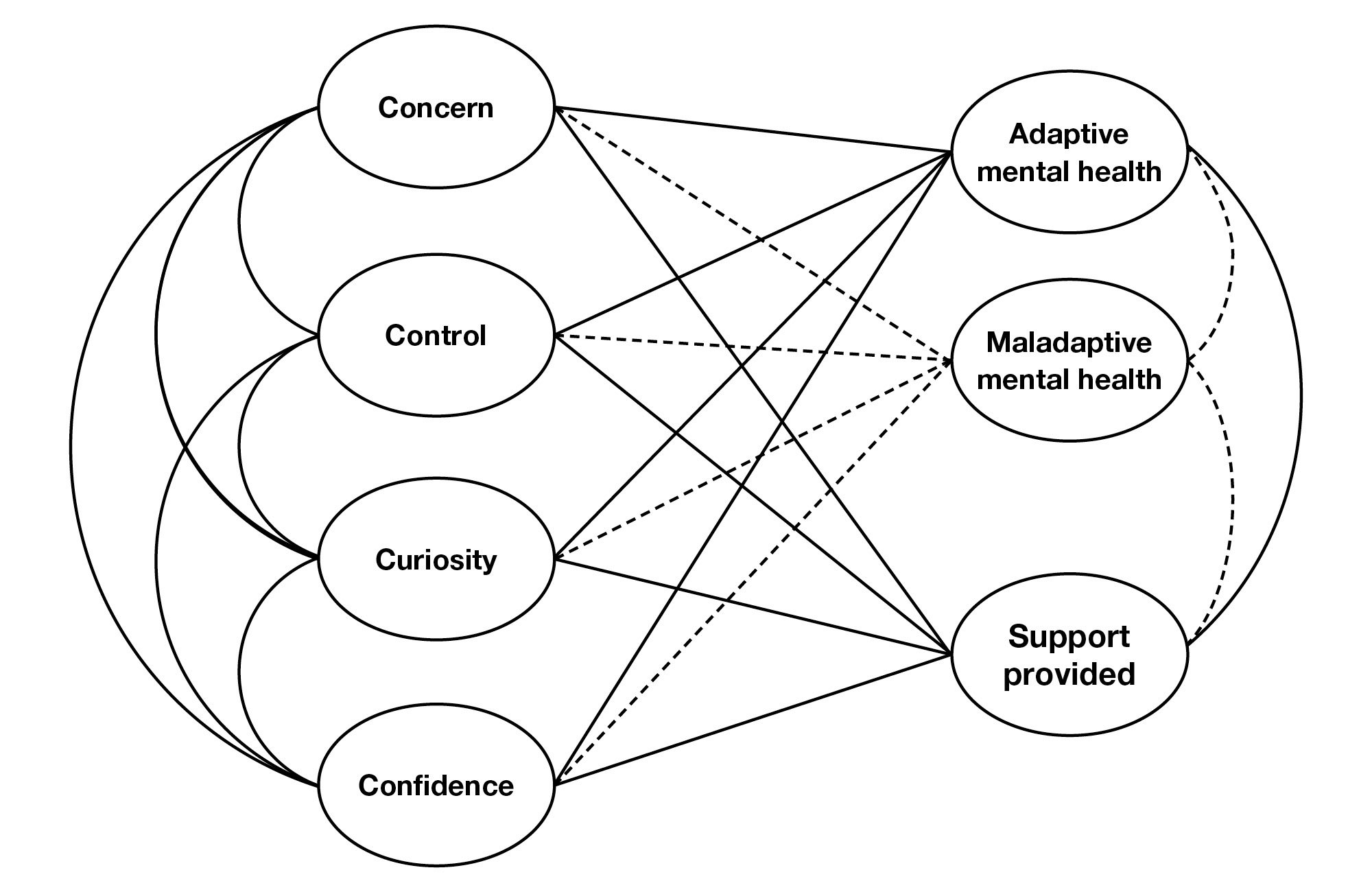

Finally, we tested a structural equation model in which coaches’ competencies were predictors of their mental health and perceived support for athletes; thus, the model included four independent variables corresponding to coaches’ CACs and three dependent variables corresponding to adaptive mental health, maladaptive mental health and perceived support for athletes. We allowed the independent and dependent variables to correlate with each other. Furthermore, we assessed the fit of the model using the same indices and criteria as in the CFA. In the hypothesised model, we expected positive relationships between CACs and coaches’ adaptive mental health, and with their ability to provide quality support to their athletes. Conversely, we expected negative relationships between coaches’ CACs and their maladaptive mental health (see Figure 1 for the hypothesised structural equation model).

Note. The dashed lines show the expected negative relationships. Concern, Control, Curiosity and Confidence are career adaptability competencies.

Results

Measurement Models

We tested a measurement model that included all instruments by using CFA. In this model, we (a) included CAAS as a four-factor latent structure to assess the coach’s perception of the extent to which he/she had each of the CACs, (b) included GHQ-12 + SWEMWBS as a two-factor latent structure to measure adaptive and maladaptive mental health, and (c) incorporated PASS-Q using a one-factor structure to measure the perception of support provided. The results of this initial model showed a good fit to the data: χ²(df) = 2592.023 (1463), RMSEA = .053 (90CI = .050 − .056), CFI = .938, TLI = .934. However, we found unexpected performance on item 2 of the GHQ-12 (e.g., “My worries have made me lose sleep”). This item had a high Modification Index (>100), affecting the factor structure, and reduced the reliability of the instrument (its removal improved Cronbach’s alpha from .85 to .87). In exploratory analyses (ESEM), it showed a high cross-loading on a different factor and a much higher correlation with item 3 than with the rest of the items of the latent factor, suggesting an inadequate relationship with the rest of the items. Conceptually, it was differentiated by its causal approach, which could bias the interpretation of the responses, as the relationship between worries and sleep disturbances is neither univocal nor linear. The exclusion of the item improved the internal structure and reliability of the questionnaire; for this reason, it was finally removed from the analysis. The resulting model showed an excellent fit to the data: χ²(df) = 2308.844 (1409), RMSEA = .048 (90CI = .045 − .052), CFI = .950, TLI = .947.

In addition, we provided evidence on CR, convergent validity and discriminant validity. First, we used McDonald’s omega to check the RC of each scale. The results were as follows: ωConcern = .847; ωControl = .816; ωCuriosity = .875; ωConfidence = .911; ωAdaptative mental health = .915; ωMaldaptative mental health = .869; ωSupport provided = .931. The value for the overall measurement model was ω = .953. All values were > .70, indicating good reliability. In terms of convergent validity, all items in the study showed significant loadings on their latent factor (> .50), with most of the factor loadings being > .70. In terms of discriminant validity, we found no cross-loaded items and correlations between latent factors were ≤ .80. Overall, we consider the results of the general measurement model to be adequate to continue with the next steps of the data analysis.

Descriptive and Correlational Analysis

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the different scales. We observed high mean values for the support dimensions, for the different dimensions of CAC and for adaptive mental health. We observed the highest scores in the confidence dimension. Furthermore, maladaptive mental health had the lowest mean score, with values close to the minimum point of the potential range of the response scale. The correlations between the latent factors were in most cases moderately high (.60 – .79). We found the exception in the correlations of confidence competence with the control competence (r = .82) and the curiosity competence (r = .80), which showed high correlations (r > .80). In contrast, maladaptive mental health showed low or no correlation with the rest of the latent factors, except for adaptive mental health, which showed a moderate and negative magnitude (r= -.50). On a theoretical level, this result makes sense since adaptive and maladaptive mental health are inversely related, but are distinct and complementary constructs. That is, the absence of adaptive mental health does not necessarily imply high maladaptive mental health.

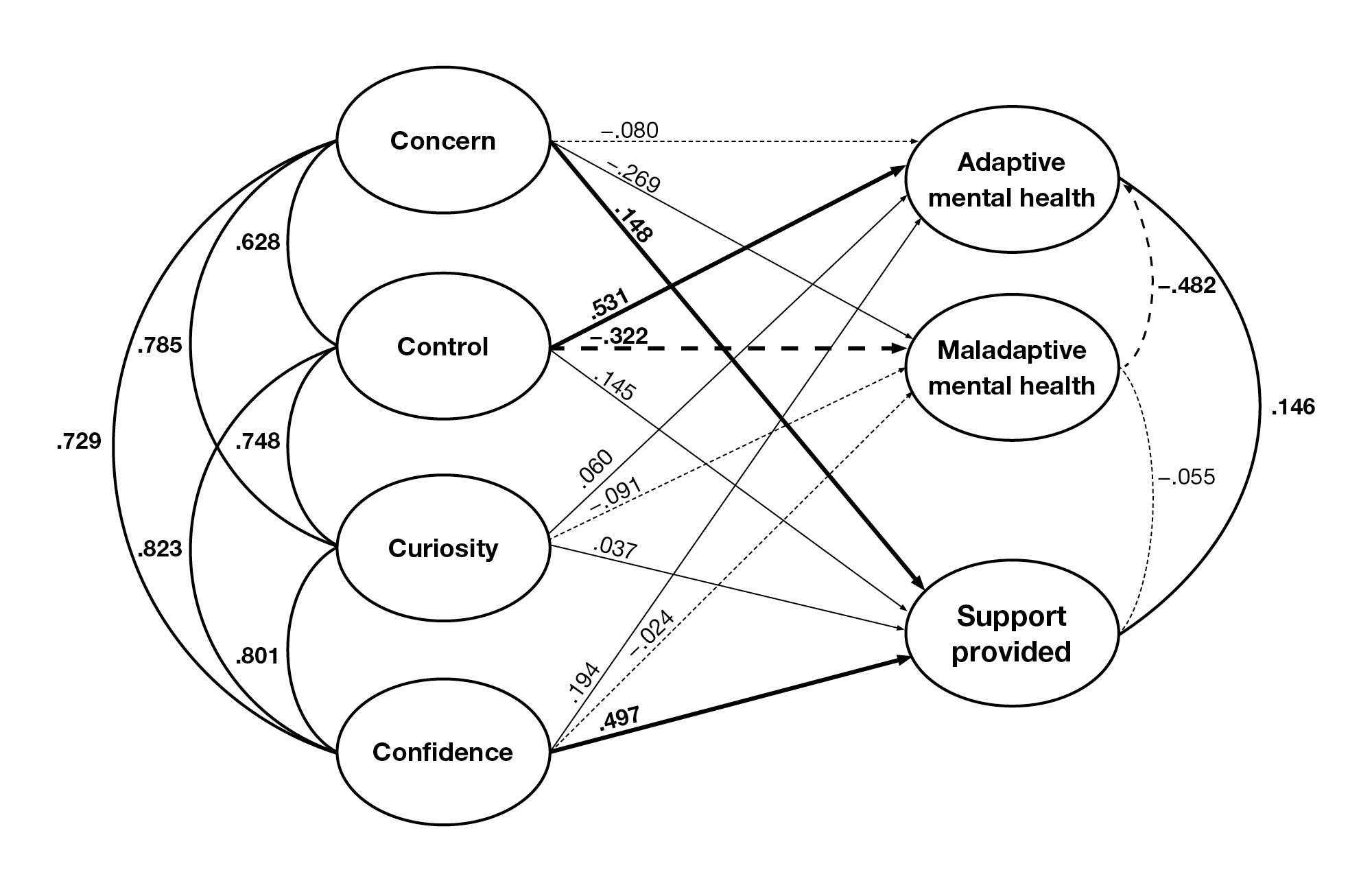

Structural Model

The results of the structural equation model (see Figure 2) showed that coaches’ CACs influenced their mental health and the support they provide to their athletes. This model showed an acceptable fit to the data χ2 (gl) = 2308.84* (1409), p < .05; RMSEA = .05 (.045 – .052); CFI = .95, TLI = .95 partially supporting the hypothesised model.

Note. Dashed lines indicate negative relationships. Thicker lines and magnitudes indicate significant relationships.

First, the concern competence showed a positive and significant association with the support provided to athletes (ß= .15). This result suggests that coaches who perceived themselves to have higher levels of concern competence tend to perceive themselves as being more supportive of their athletes. Nonetheless, it should be noted that the magnitude of this association is considered low (Hair et al., 2009). Second, control competence predicted both types of mental health, which was positive for adaptive mental health (ß= .53) and negative for maladaptive mental health (ß= -.32). Thus, the results indicated that when coaches perceived themselves as more competent in their control competence, this promoted their own adaptive mental health and helped to decrease their maladaptive mental health.

Third, confidence competency was also a positive and significant predictor of the support factor (ß= .50). That is, coaches who perceived themselves to have higher levels of confidence competence also perceived themselves to be more supportive of their athletes. In contrast, curiosity competence was not significantly related to the study outcome variables. Besides, the model allowed for correlations between variables at the same level. In this regard, the results found high and moderately high positive correlations between all the CAC. In turn, we observed a negative correlation between adaptive and maladaptive forms of mental health (r = -.48). Finally, regarding the relationships between the dependent variables, we did not observe relevant correlations between perceived support and both types of mental health.

Discussion

This study represents a significant advance in the understanding of the CA of training coaches. In particular, it helps to delve into the specific effects of the four CACs of these coaches on their mental health and the perception of the support they offer to their athletes. This population, which invests its efforts, resources and time in training, needs to have and coordinate an alternative career, as training is not a full-time job for them (Hinojosa-Alcalde et al., 2023). In this regard, our results, which partially support the hypothesised model, show that CACs appear to promote healthier trajectories (Cosín-Miguel et al., 2023) by predicting both their mental health (Johnston et al., 2013; Maggiori et al., 2013; Ronkainen et al., 2020) and their perception of providing support to their athletes (Taber & Blankemeyer, 2015; Teck Koh et al., 2019). However, the degree of influence of each competence varies considerably, with control and confidence competencies being the most relevant in predicting the CACs of training coaches.

In our work, curiosity competence, which promotes the search for information and opportunities (Savickas & Porfeli, 2012), has not shown significant relationships with the target variables of mental health and perceived support. In contrast, control competence positively predicts adaptive mental health and negatively predicts maladaptive mental health. This finding suggests that the development of this competence, which includes self-regulation, and adaptation to the environment and other situations that may occur during their coaching careers (e.g., when considering how to get to the next step in order to progress as coaches) is linked to adaptive mental health. This reinforces the view that CAC of control is an important resource for perceived job security (Maggiori et al., 2013), life satisfaction (Konstam et al., 2015), as well as happiness and reduction of work stress (Johnston et al., 2013), and supports career and organisational continuity (Omar & Noordin, 2013). In addition, control CAC has already been positively linked to positive affective relations (e.g., active, excited, inspired, proud, interested), and negatively linked to negative affective relations (e.g., scared, embarrassed, distressed, annoyed, irritated) (Konstam et al., 2015). Although using a different model and in a close population, similar results have been recognised in the “Career and Lifestyle Management” competence in the research by Smismans et al. (2021) on competencies needed in athletes, transferable to the labour market, where a lack of self-regulation and adaptation would jeopardise the mental health and well-being of athletes.

Confidence and concern competencies are predictors of coaches’ perceived support for their athletes, with confidence being the most important determinant. Coaches who are self-confident, design life options, and perceive themselves as capable of solving problems and overcoming obstacles tend to be more supportive of their athletes. These results are aligned with Zacher’s (2014) findings linking confidence and concern CACs to self-assessed performance, and with those linking of CAC of confidence to proactive skill development (Taber & Blankemeyer, 2015). This suggests that coaches with high levels of CAC of confidence tend to positively self-evaluate their performance in supporting their athletes, while developing skills to provide support, such as listening, offering comfort and reassurance, reinforcing feelings of competence or self-worth, and providing help and constructive criticism (Freeman et al., 2011). Similarly, our results align with those of Duffy et al. (2015), who found that CACs of control and confidence were key predictors of academic satisfaction in the transition to university, in part due to a greater perceived freedom to choose their future.

Practical implications

Our results suggest complementary practical considerations that could help coaches develop their CACs, placing them within a broader context that enriches the interpretation of the findings. In particular, it seems appropriate to create environments, trainings and interventions with the aim of supporting coaches’ responsibility for shaping their future (i.e., control), and fostering their ability to overcome specific vocational barriers (i.e., confidence; Savickas & Porfeli, 2012). We recommend clubs, sports federations and training institutions to offer opportunities for personal improvement as well as to progress in their role as coaches. For example, by implementing mentoring between coaches where more experienced coaches guide younger coaches, creating seminars where they can hear stories from peers and how they solved them, including modules on skills such as planning, stress management and negotiation to help them gain confidence in key areas for their development, designing workshops where coaches practise how to deal with real challenges in their context (Cushion, 2006; Leeder & Sawiuk, 2021). In this sense, it seems reasonable for clubs to ensure flexible conditions adapted to the degree of pressures and lack of stability (e.g., female coaches); (García-Solà et al., 2023). Moreover, providing constructive feedback on coaches’ performance boosts their confidence, which could also lead to improvements in support for their athletes. This way, they would maintain the vitality of their coaches, reduce stress, and improve the motivation of both coaches and their athletes (Cosín-Miguel et al., 2023).

Setting clear and achievable goals (Morelló-Tomás et al., 2018), both in their careers and in practice with their athletes, could help coaches to increase their sense of control and self-confidence. The CAAS questionnaire could serve as a self-assessment tool that allows coaches to keep track of their competencies and vocational needs (De Brandt et al., 2018). On the other hand, Career Assistance Programmes (Torregrossa, 2020) can provide support for the optimisation of coaches’ careers, protecting their mental health and promoting their well-being. This investment will bring short-term benefits to those who make it, ensuring continuity for coaches, fostering a supportive and trusting work climate, likely reducing job losses, and even producing beneficial effects between the different spheres of coaches’ lives (e.g., work and family); (Hinojosa-Alcalde et al., 2023).

Limitations and future research

Our study has focused on training coaches, an understudied group facing idiosyncratic challenges and demands. We included coaches of various sports, competitive levels, ages, years of experience and genders, but the type of sampling did not allow us to explore differences between sample subgroups. Nonetheless, it allowed for explanatory analyses to be carried out with the entire group, providing a first approximation to the reality of this population. In this regard, analysing differences between participant groups could reveal varying relationships in coaches’ CACs. We propose to continue the present research with studies in which, with a larger sample and depending on the type of trajectory, both the mental health of the coaches and the perceived support for their athletes are evaluated.

Conclusions

In conclusion, CACs, especially those related to control and confidence, predict the mental health of training coaches and their perceived support for their athletes. As a result, working conditions, training programmes, and sport in general should ensure support for coaches on their path towards professionalisation.

Acknowledgements

This work has been carried out thanks to the support of two projects: “Promoción de Carreras Duales Saludables en el Deporte / Promotion of Healthy Dual Careers, HeDuCa” (RTI2018-095468-B-100) and the R&D project “Entornos Saludables hacia el Alto Rendimiento Deportivo / Healthy Environment throughout Athletic Careers, HENAC” (PID2022-138242OB-I00). Both projects have been funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities and coordinated by the Grup d’estudis de Psicologia de l’Activitat Física i l’Esport (GEPE-GRECSE).

References

[1] Alcaraz Garcia, S., Torregrossa, M., & Viladrich, C. (2015). El lado oscuro de entrenar: influencia del contexto deportivo sobre la experiencia negativa de entrenadores de baloncesto. Revista de Psicología Del Deporte, 24(1), 0071–0078. https://ddd.uab.cat/record/128718

[2] Borrueco, M., Torregrossa, M., Pallarès, S., Vitali, F., & Ramis, Y. (2023). Women coaches at top level: Looking back through the maze. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 18(2), 327–338. doi.org/10.1177/17479541221126614

[3] Cheung, G. W., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S., & Wang, L. C. (2023). Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling:A review and best-practice recommendations. In Asia Pacific Journal of Management (Vol. 41, Issue 2). Springer US. doi.org/10.1007/s10490-023-09871-y

[4] Chroni, S. A., Olusoga, P., Dieffenbach, K., & Kenttä, G. (2024). Coaching Stories: Navigating Storms, Triumphs, and Transformations in Sport. Taylor and Francis. doi.org/10.4324/B23184

[5] Cosín Miguel, M., Alcaraz García, S., & Ramis Laloux, Y. (2023). Del césped al banquillo: trayectorias de futbolistas semiprofesionales en su transición de jugar a entrenar. Apuntes de Psicología, 41(1), 21–28. doi.org/10.55414/ap.v41i1.1524

[6] Cushion, C. (2006). Mentoring. In The Sports Coach as Educator: Re-Conceptualising Sports Coaching (R. Jones, pp. 128–144). doi.org/10.4324/9780203020074

[7] Cutrona, C. E., & Russell, D. W. (1990). Type of social support and specific stress: Toward a theory of optimal matching. Social Support: An Interactional View, 9(1), 3–22. psycnet.apa.org/record/1990-97699-013

[8] De Brandt, K., Wylleman, P., Torregrossa, M., Veldhoven, N. S. Van, Minelli, D., Defruyt, S., & Knop, P. De. (2018). Exploring the factor structure of the Dual Career Competency Questionnaire for Athletes in European pupil- and student-athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2018, 1–18. doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2018.1511619

[9] Duffy, R. D., Douglass, R. P., & Autin, K. L. (2015). Career adaptability and academic satisfaction: Examining work volition and self efficacy as mediators. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 90, 46–54. doi.org/10.1016/J.JVB.2015.07.007

[10] Feu, S., García-Rubio, J., Antúnez, A., & Ibáñez, S. (2018). Coaching and Coach Education in Spain: A Critical Analysis of Legislative Evolution. International Sport Coaching Journal, 5(3), 281–292. doi.org/10.1123/ISCJ.2018-0055

[11] Freeman, P., Coffee, P., & Rees, T. (2011). The PASS-Q: the perceived available support in sport questionnaire. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 33(1), 54–74. doi.org/10.1123/JSEP.33.1.54

[12] García-Solà, M., Ramis, Y., Borrueco, M., & Torregrossa, M. (2023). Dual Careers in Women’s Sports: A Scoping Review. Apunts. Educacion Fisica y Deportes, 154, 16–33. doi.org/10.5672/APUNTS.2014-0983.ES.(2023/4).154.02

[13] Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.).Prentice-Hall. books.google.es/books/about/Multivariate_Data_Analysis.html?id=VvXZnQEACAAJ&redir_esc=y

[14] Hinojosa-Alcalde, I., Soler, S., Vilanova, A., & Norman, L. (2023). Balancing Sport Coaching with Personal Life. Is That Possible? Apunts. Educacion Fisica y Deportes, 154, 34–43. doi.org/10.5672/APUNTS.2014-0983.ES.(2023/4).154.03

[15] Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

[16] Ibáñez, S. J., García-Rubio, J., Antúnez, A., & Feu, S. (2019). Coaching in Spain Research on the Sport Coach in Spain: A Systematic Review of Doctoral Theses. International Sport Coaching Journal, 6(1), 110–125. doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2018-0096

[17] Johnston, C. S. (2016). A Systematic Review of the Career Adaptability Literature and Future Outlook. Journal of Career Assessmen, 26(1), 1–28. doi.org/10.1177/1069072716679921

[18] Johnston, C. S., Luciano, E. C., Maggiori, C., Ruch, W., & Rossier, J. Ô. (2013). Validation of the German version of the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale and its relation to orientations to happiness and work stress. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 295–304. doi.org/10.1016/J.JVB.2013.06.002

[19] Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. doi.org/10.2307/3090197

[20] Konstam, V., Celen-Demirtas, S., Tomek, S., & Sweeney, K. (2015). Career Adaptability and Subjective Well-Being in Unemployed Emerging Adults. Journal of Career Development, 42(6), 463–477. doi.org/10.1177/0894845315575151

[21] Leeder, T. M., & Sawiuk, R. (2021). Reviewing the sports coach mentoring literature: a look back to take a step forward. Sports Coaching Review, 10(2), 129–152. doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2020.1804170

[22] Li, Y., Guan, Y., Wang, F., Zhou, X., Guo, K., Jiang, P., Mo, Z., Li, Y., & Fang, Z. (2015). Big-five personality and BIS/BAS traits as predictors of career exploration: The mediation role of career adaptability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 89, 39–45. doi.org/10.1016/J.JVB.2015.04.006

[23] Maggiori, C., Johnston, C. S., Krings, F., Massoudi, K., & Rossier, J. Ô. (2013). The role of career adaptability and work conditions on general and professional well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 437–449. doi.org/10.1016/J.JVB.2013.07.001

[24] Maggiori, C., Rossier, J., & Savickas, M. L. (2015). Career Adapt-Abilities Scale–Short Form (CAAS-SF): Construction and Validation. Journal of Career Assessment, 25(2), 312–325. doi.org/10.1177/1069072714565856

[25] Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., & Wen, Z. (2004). In Search of Golden Rules: Comment on Hypothesis-Testing Approaches to Setting Cutoff Values for Fit Indexes and Dangers in Overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) Findings. Structural Equation Modeling, 11(3), 320–341. doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1103_2

[26] McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test Theory: A Unified Treatment. Lawrence Erlbaum. books.google.cl/books?id=2-V5tOsa_DoC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

[27] McLean, K. N., & Mallett, C. J. (2012). What motivates the motivators? An examination of sports coaches. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 17(1), 21–35. doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2010.535201

[28] Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes (2024). (2024). Yearbook of Sports Statistics 2024. In DEPORTEData. www.educacionfpydeportes.gob.es/dam/jcr:fbf05df0-5e3f-4b57-9d5b-6588d4ad34a9/aed-2024.pdf

[29] Morelló Tomás, E., Vert Boyer, B., & Navarro Barquero, S. (2018). Establecimiento de objetivos en el currículum formativo de los futbolistas. Revista de Psicología Aplicada al Deporte y El Ejercicio Físico, 3(1), 1–9. doi.org/10.5093/RPADEF2018A7

[30] Muthén L, M. B. (2012). Mplus Editor (version 7.0) [Software].

[31] Negru-Subtirica, O., Pop, E. I., & Crocetti, E. (2015). Developmental trajectories and reciprocal associations between career adaptability and vocational identity: A three-wave longitudinal study with adolescents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 88, 131–142. doi.org/10.1016/J.JVB.2015.03.004

[32] Ojala, J., Nikander, A., Aunola, K., De Palo, J., & Ryba, T. V. (2023). The role of career adaptability resources in dual career pathways: A person-oriented longitudinal study across elite sports upper secondary school. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 67. doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2023.102438

[33] Omar, S., & Noordin, F. (2013). Career Adaptability and Intention to Leave among ICT Professionals: An Exploratory Study. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology - TOJET, 12(4), 11–18.

[34] Ronkainen, N. J., Sleeman, E., & Richardson, D. (2020). “I want to do well for myself as well!”: Constructing coaching careers in elite women’s football. Sports Coaching Review, 9(3), 321–339. doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2019.1676089

[35] Rynne, S. (2014). “Fast track” and “traditional path” coaches: affordances, agency and social capital. Sport, Education and Society, 19(3), 299–313. doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.670113

[36] Safrit M, W. T. (1995). Introduction to measurement in physical education and exercise science (3rd eds) (Mosby).

[37] Sánchez-López, M. D. P., & Dresch, V. (2008). The 12-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12): Reliability, external validity and factor structure in the Spanish population. Psicothema, 20(4), 839–843

[38] Savickas, M. L. (1997). Career adaptability: An integrative construct for life-span, life-space theory. Career Development Quarterly, 45(3), 247–259. doi.org/10.1002/J.2161-0045.1997.TB00469.X

[39] Savickas, M. L., & Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 661–673. doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.011

[40] Schinke, R. J., Stambulova, N. B., Si, G., & Moore, Z. (2018). International society of sport psychology position stand: Athletes’ mental health, performance, and development. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(6), 622–639. doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2017.1295557

[41] Shah, N., Cader, M., Andrews, B., McCabe, R., & Stewart-Brown, S. L. (2021). Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): performance in a clinical sample in relation to PHQ-9 and GAD-7. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 19(1), 1–9. doi.org/10.1186/S12955-021-01882-X/TABLES/4

[42] Smismans, S., Wylleman, P., De Brandt, K., Defruyt, S., Vitali, F., Ramis, Y., Torregrossa, M., Lobinger, B., Stambulova, N., & & Cecić Erpič, S. (2021). From elite sport to the job market: Development and initial validation of the Athlete Competency Questionnaire for Employability (ACQE) Del deporte de elite al mercado laboral: Desarrollo y validación inicial del Cuestionario de Competencias de Deportista. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 16(47), 39–48. doi.org/10.12800/CCD.V16I47.1694

[43] Taber, B. J., & Blankemeyer, M. (2015). Future work self and career adaptability in the prediction of proactive career behaviors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 86, 20–27. doi.org/10.1016/J.JVB.2014.10.005

[44] Teck Koh, K., Kokkonen, M., & Rang Bryan Law, H. (2019). Coaches’ implementation strategies in providing social support to Singaporean university athletes: A case study. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 14(5), 681–693. doi.org/10.1177/1747954119876099

[45] Torregrossa, M., Regüela, S., & Mateos, M. (2020). Career assistance programmes. In The Routledge International Encyclopedia of Sport and Exercise Psychology (pp. 73–78.)

[46] Wilkins, K. G., Santilli, S., Ferrari, L., Nota, L., Tracey, T. J. G., & Soresi, S. (2014). The relationship among positive emotional dispositions, career adaptability, and satisfaction in Italian high school students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(3), 329–338. doi.org/10.1016/J.JVB.2014.08.004

[47] Zacher, H. (2014). Career adaptability predicts subjective career success above and beyond personality traits and core self-evaluations. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84(1), 21–30. doi.org/10.1016/J.JVB.2013.10.002

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: 10, November 2024

Accepted: 25, March 2025

Published: 1, July 2025

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en