Application of Indirect Observation in High-Performance Judo From a Mixed Methods Perspective

*Corresponding author: Rubén Maneiro rubenmaneirodios@gmail.com

Cite this article

Rodríguez-Rodríguez, C., Amatria-Jiménez, M., & Maneiro, R. (2025). Application of indirect observation in high-performance judo from a mixed methods perspective. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 162, 43-52. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2025/4).162.05

Abstract

This study analyzed, for the first time, the application of indirect observation to high performance judo, covering both male and female categories. Indirect observation involves, to a large extent, the analysis of textual material generated secondarily from transcriptions of verbal behavioral records, such as interviews. The aim of this study was to apply this methodology to the field of elite judo in order to explore the existence of communicative patterns related to technical and tactical adaptations to the opponent, aimed at achieving IPPON. Nine in-depth interviews were conducted with the following participants: Olympic judokas (n = 3), strength and conditioning coach of an Olympic judoka (n = 1), judo instructors in the Bachelor’s Degree in Physical Activity and Sports Sciences (n = 3), and club coaches (n = 2). These interviews were analyzed by means of indirect observation through a quantitizing process based on the construction of an ad hoc observation instrument. The transcripts were segmented into textual units and a code matrix was elaborated that allowed a polar coordinate analysis to be carried out. This analysis facilitated the detection of communicative patterns related to the behavior “technical and tactical adaptations based on the opponent”. The results showed statistically significant associations between these adaptations and variables such as standing judo and judo groundwork, dominance in kumikata, the time period of the match, and the score. The use of indirect observation proves to be a valuable tool for future studies focused on gathering athletes’ perspectives and contributes to giving scientific value to their views on various aspects of the sport.

Introduction

Indirect observation is a relatively new concept within systematic observation (Anguera & Hernández-Mendo, 2016; Anguera et al., 2018), which falls under a broader paradigm, namely mixed methods (Castañer et al., 2013). It focuses on the analysis of textual material that is generated indirectly from transcriptions of audio recordings in natural contexts, such as conversations or group discussions, or directly from narratives such as complaint letters, interviews, or forum posts. This type of material represents a highly important data source, and its availability is constantly expanding thanks to new technologies that facilitate the capture, dissemination, and storage of data (Anguera et al., 2017).

What distinguishes indirect observation from other methodologies used to study opinions (such as Grounded Theory, discourse analysis, or thematic analysis) is its mixed qualitative-quantitative approach, in which the development of an observation instrument based on a category system enables a more objective and structured coding of discourse (Iván-Baragaño et al., 2023a). This makes this methodology optimal when seeking to analyze verbalizations from a systematic perspective.

The application of indirect observation offers a rigorous and systematized perspective to analyze verbal discourses through textual units and their subsequent coding (Anguera et al., 2018). It allows converting qualitative information into observable and analyzable data with quantitative criteria and provides objectivity and replicability to the analysis of opinions. Indirect observation not only allows us to capture the manifest content of the discourse (forums, interviews…), but also patterns, regularity and relationships between dimensions of analysis that would not be detectable with descriptive methods.

Although it has been successfully applied in other fields (García-Fariña et al., 2018; Alcover et al., 2019; Arias-Pujol & Anguera, 2020; Del Giacco et al., 2020; Alvarado-Álvarez et al., 2021), it is in the field of sport where it has gained the most traction (Sarmento et al., 2014; Sarmento et al., 2020; Nunes et al., 2022; Iván-Baragaño et al., 2023a). Traditionally, sports scientists have focused on data obtained through direct observation of behaviors (either in situ or through video/audio recordings), based on a direct observation strategy (Gamero-Castillero et al., 2022; Maneiro, 2021; Barbero et al., 2024). In contrast, indirect observation has enabled the scientific validation of the voices of athletes and coaches, offering insights into their opinions on various technical and tactical-strategic aspects of sport.

Within the field of team sports such as basketball, the study by Nunes et al. (2022) asks various high-performance coaches about the effectiveness of the pick & roll. The interviews revealed varying levels of confidence in this tactical element as an offensive resource. Coaches viewed the pick & roll as a key action for generating advantages, which allowed them to analyze the opponent and decide whether to finish the play or continue with the established offensive plan.

In men’s soccer, Sarmento et al. (2014) interviewed eight coaches from the Portuguese league about the most important variables influencing attack. Although the coaches’ assessments varied, all concluded that the choice of attack type (in this case, the counterattack) is directly related to the type of players, defensive style, and the zone where the ball is recovered. Furthermore, in another study, Sarmento et al. (2020) analyzed coaches from AS Monaco and concluded that the findings from direct observation were consistent with the information provided in the interviews—both regarding the importance of certain players within the team structure and the overall game system. They also emphasized that cooperation between scientists and coaching staff should be implemented regularly. Finally, in the context of women’s soccer, Iván-Baragaño et al. (2023a) interviewed eight professional Spanish female players and coaches and found that the interview results suggested a statistically significant association between success in women’s soccer and various tactical-strategic criteria—results that aligned with those obtained through direct observation (Iván-Baragaño et al., 2021; Iván-Baragaño et al., 2023b).

In short, the inclusion of indirect observation based on interviews with sports professionals provides valuable information for gaining a more comprehensive understanding of competitive reality and complements data obtained through direct observation. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine which criteria influence technical and tactical adaptations based on the opponent, based on semistructured interviews with judokas, coaches, strength and conditioning coaches, and judo instructors in the Bachelor’s Degree in Physical Activity and Sport Sciences.

Method

Design

To carry out this study, the observational methodology was applied (Anguera, 1979), based on the transcription of in-depth interviews conducted with coaches and judokas. The design was nomothetic—multiple units of study—, punctual—a single session, although with intrasessional follow-up—, and multidimensional—multiple levels of response, as reflected in the observation instrument— (Anguera et al., 2011). The protocol proposed by Portell et al. (2015) was followed to strengthen the methodological structure of the article.

Due to incomplete perceptibility of the object of study, indirect observation was used (Anguera et al., 2018), within the mixed methods paradigm (Anguera et al., 2021), to analyze transcribed oral behavior.

Participants

A total of nine interviews were conducted to gather the opinions of: Olympic judokas (n = 3), the strength and conditioning coach of an Olympic judoka (n = 1), judo instructors in the Bachelor’s Degree in Physical Activity and Sport Sciences (n = 3), and club coaches (n = 2). All interviews were conducted in 2019 and 2020.

Based on these criteria (Anguera, 2003), the nine interviews conducted in this study were semistructured (the questions followed a flexible guide that allowed the interviewer to adapt to the flow of the conversation), non-directive (the questions followed a natural course and focused on the interviewee, allowing them to freely express their ideas, emotions, and experiences), and were conducted in person and individually, with a research purpose. To this end, the interviewer traveled to the different locations agreed upon with the interviewees. The interviews were also recorded using electronic devices in order to ensure optimal interpretation of speech and comprehension of language (data, discursive aspects, narratives, interwoven stories, etc.). The intensive nature of the study (gathering extensive data from each case) meant that although the number of interviews was small, a large amount of detailed and rich information was obtained from each one. Therefore, each interview became a complex case with multiple dimensions and analyzable data for indirect observation studies. The number of interviews was considered sufficient for this study, as in others (Iván-Baragaño et al., 2023a; Sarmento et al., 2020).

On the other hand, the inclusion criteria for selecting the experts interviewed were: being or having been a high-performance athlete in judo, being a judo teacher or coach, being part of the Spanish Judo Federation’s coaching staff, being a scientific researcher in the field of judo, or being the strength and conditioning coach of high-performance judokas.

Instruments

Semi-structured interviews

Each of the interviews consisted of a total of 26 questions. Its design was based on three criteria: technical aspects of high-performance judo, tactical aspects and spatial-temporal management during matches. Once the interviews were conducted, they were transcribed into Microsoft Word documents. Following transcription, and as noted by Anguera (2020), the next step was to “liquefy the text.” The textual material was segmented into textual units to systematize the information, facilitate its analysis, and enhance its significance. In this study, segmentation into textual units followed orthographic and syntactic criteria, with the same purpose of systematizing the information, enabling its analysis, and adding significance. After coding the textual units for quantitative treatment and consulting the theoretical framework, the indirect observation instrument was constructed.

Indirect observation instrument

The indirect observation instrument designed for this study was developed using an ad hoc approach that combined two perspectives: a bottom-up approach, based on the responses obtained and their relation to the theoretical framework and regulations, and a top-down approach, starting from the theoretical framework and cross-checked with the interviewees’ responses. Its development involved a gradual process of refinement and specification of the dimensions and subdimensions that compose it.

The final instrument adopted a mixed format, combining a field format with category systems, which allowed for an effective approach to the high complexity of the phenomenon under study (Caprara & Anguera, 2019; Iván-Baragaño et al., 2023a). It was structured into 7 dimensions and 13 subdimensions. From some subdimensions, behavior catalogs were created and organized into open lists, ensuring mutual exclusivity of the items. Other subdimensions were used to build category systems based on theoretical frameworks, meeting the criteria of exhaustiveness and mutual exclusivity.

For each category and behavior included in the instrument, detailed descriptions were provided, accompanied by examples and counterexamples derived from the participants’ responses. The indirect observation instrument, named the IndirectJudoBS Observation Instrument, is presented in Table 1.

Recording tool

The free software Lince Plus (Soto-Fernández et al., 2021), which is highly applicable in observational methodology, was used to record and code the textual units analyzed.

The use of this software allowed the recording, coding and subsequent export of the code matrix obtained to the formats required for subsequent analysis.

Procedure

Data quality control was conducted through the adaptation of Cohen’s kappa coefficient (1960), following Krippendorff’s (2013) proposal, to the canonical agreement coefficient. The reliability of the recording was assessed using Cohen’s kappa coefficient (1960) in its intraobserver modality, yielding a value of 1 (Table 2), which is considered appropriate in the context of this study (Landis & Koch, 1977). In addition, the consensual agreement method (Lapresa et al., 2021) was used as a qualitative procedure for data quality control. This was carried out by three of the researchers participating in the study. The process consisted of three recordings (textual unit segmentation and coding) using the same indirect observation instrument and applying the intraobserver modality. Following the recommendations of Anguera (2020), three recordings were deemed appropriate, as indirect observation poses a higher risk of interference and subjectivity compared to direct observation. After transcribing the recorded interviews, they were segmented into textual units based on orthographic and syntactic criteria (Krippendorff, 2018).

These units were recorded and coded using indirect observation, a process that involved the quantitizing of the data (Anguera, 2020; Anguera et al., 2021). That is, the qualitative data obtained from the interviews were coded using the observation instrument, allowing for the generation of a code matrix (Table 2). This matrix facilitated the subsequent application of a robust quantitative analysis.

Data analysis

To construct a map of interrelations between different behaviors, a polar coordinate analysis was conducted (which has also been applied in other studies on indirect observation in sports, such as Sarmento et al., 2014; Iván-Baragaño et al., 2023a; Nunes et al., 2022). In this analysis, the target or focal behavior was C1ADAPTRI (existence of technical and tactical adaptations based on the opponent), while the same behaviors were considered as conditioned. This focal behavior was selected because interviewees identified it as a key variable for success during matches and also because it has been used as a reference behavior in other research (e.g., Franchini et al., 2005).

Based on these data, a vector map was created to illustrate the relationships between the focal behavior and the conditioned behaviors. The length and angle of each vector (one for each conditioned behavior) were calculated.

Only behaviors with a radius equal to or greater than 1.96 were included.

All analyses were performed using the open-source software HOISAN (v 2.0) (Hernández-Mendo et al., 2012), except for the lag 0 calculation, which was conducted using the open-source software GSEQ5 (Bakeman & Quera, 2011).

The selected focal behavior was C1ADAPTRI (existence of technical and tactical adaptations by judokas based on the opponent), and all other behaviors were treated as conditioned behaviors.

Results

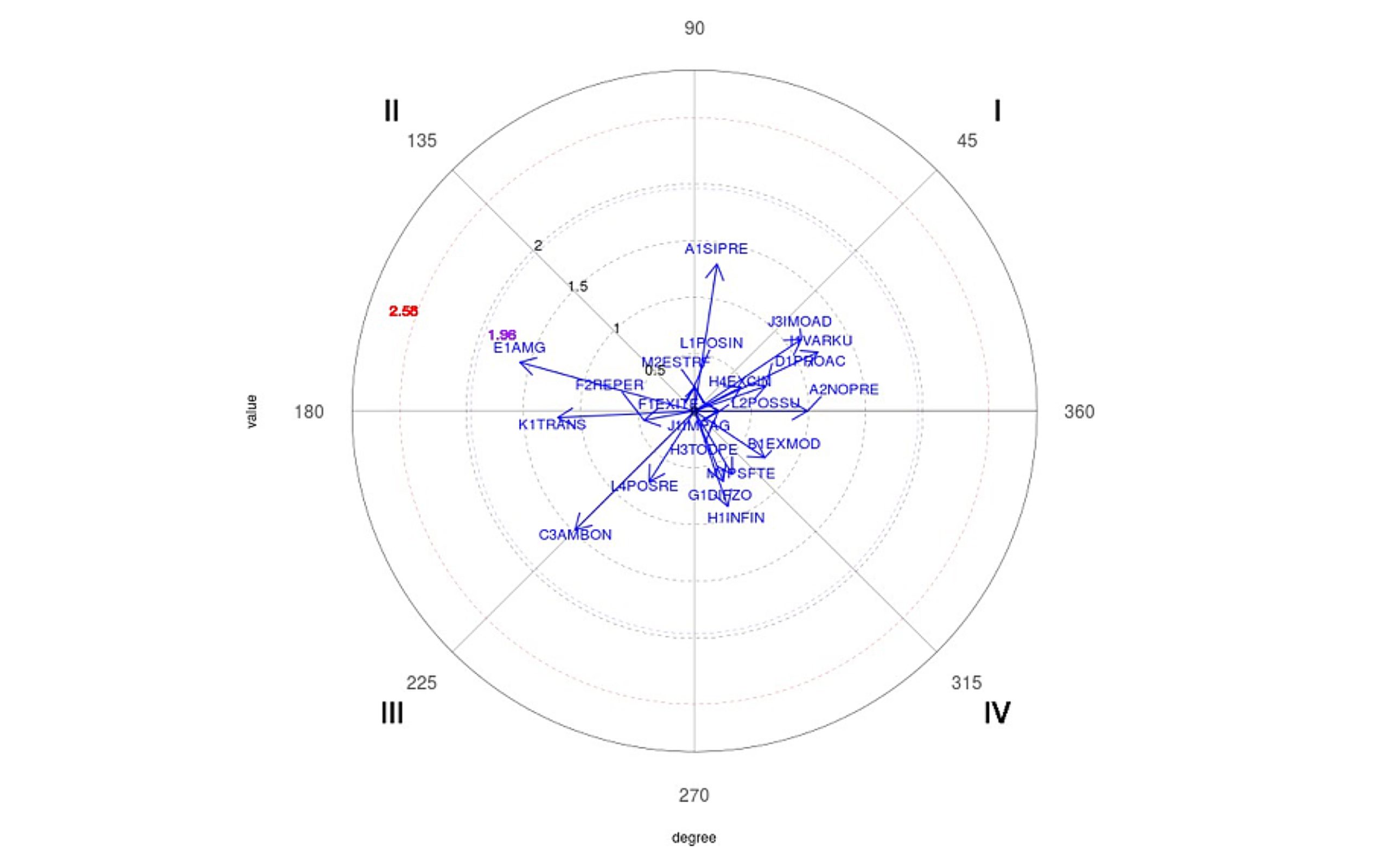

The results of the polar coordinate analysis are presented below (Table 3, Figure 1). The vectors indicate the type of relationship between the focal behavior and each conditioned behavior, and vice versa, as well as the intensity of these relationships. Based on these values, a vector map was constructed showing the relationships between the focal behavior and the remaining conditioned behaviors.

Table 3

Relationship between the focal category (C1ADAPTRI/Existence of technical-tactical adaptations based on the opponent), and the rest of the categories

The results shown in Table 3 and Figure 1 indicate that in Quadrant I, where the focal behavior activates the paired behavior both prospectively and retrospectively (mutual activation), the following paired behaviors are located: A1SIPRETEC (existence of technical predominance in standing and groundwork judo situations depending on weight category, sex, and/or age), with a radius of 1.31 and an angle of 81.34°; A2NOPRETEC (absence of technical predominance in standing and groundwork judo situations depending on weight category, sex, and/or age), with a radius of 0.99 and an angle of 0°; D1PROAC (proactive intention of the judoka during the matches), with a radius of 0.66 and an angle of 19.29°; F1EXITECTA (use of successful technical-tactical behaviors in situations of scoreboard disadvantage and nearing the end of the match), with a radius of 0.21 and an angle of 90°; H3TODPER (all match time periods are crucial in a judo bout), with a radius of 0.21 and an angle of 0°; H4EXCINPER (all time periods except the initial one are crucial in a judo bout), with a radius of 0.46 and an angle of 27.32°; I1VARKUM (importance of kumikata and its variations), with a radius of 1.2 and an angle of 25.61°; J1IMPAG (imposition of kumikata in situations where the opponent hinders its execution), with a radius of 0.21 and an angle of 0°; J3IMOADAP (imposition or adaptation of kumikata based on the situation), with a radius of 1.13 and an angle of 34.01°; L1POSIND (groundwork performed from an individualized position and from the grip), with a radius of 0.22 and an angle of 90°; L2POSSUP (groundwork performed from a supine position), with a radius of 0.22 and an angle of 0°; M2ESTRFTT (strategic, physical, technical, and tactical requirements a judoka must meet to succeed), with a radius of 0.21 and an angle of 90°.

In Quadrant II, where the focal behavior inhibits the paired behavior prospectively and activates it retrospectively, the paired behavior E1AMG is found, with a radius of 1.59 and an angle of 164.32°. Based on the results, it is plausible to think that for judokas, the use of feints and deceptions during matches may serve as an effective strategy to create uncertainty about their actual technical-tactical intentions.

In Quadrant III, where the focal behavior inhibits the paired behavior both prospectively and retrospectively, the following behaviors are located: C3AMBONIN (depending on the situation, existence of technical-tactical adaptations or maladaptations by the judoka based on the opponent), with a radius of 1.48 and an angle of 225°; F2REPERT (use of a specific repertoire in situations of scoreboard disadvantage and nearing the end of the match), with a radius of 0.45 and an angle of 190.41°; K1TRANSPS (foot-to-ground transitions are essential during judo matches), with a radius of 1.2 and an angle of 182.79°; L4POSRECEJ (groundwork based on the position of the performer and the receiver), with a radius of 0.74 and an angle of 237.37°.

Finally, in Quadrant IV, where the focal behavior activates the presence of the paired behavior prospectively but not retrospectively, the following behaviors are found: B1EXMOD (presence of technical and tactical trends in current judo), with a radius of 0.74 and an angle of 326.31°; G1DIFZON (existence of multiple optimal working zones within the tatami), with a radius of 0.67 and an angle of 292.09°; H1INFINPER (initial and/or final time periods are crucial in a judo bout), with a radius of 0.89 and an angle of 289.17°; M1PSFTECTAC (psychological, physical, technical, and tactical requirements a judoka must meet to succeed).

Discussion

The present study was conducted with the aim of detecting regularities in the existence of technical and tactical adaptations based on the opponent, as well as performing an interrelational analysis of related behaviors, based on in-depth interviews with coaches, judokas, physical trainers, and judo instructors. In this regard, in the communicative pattern of the interviews conducted, various behaviors were found to be linked to the existence of technical and tactical adaptations by judokas based on the opponent. These communicative patterns were accurately identified thanks to the structured coding process typical of indirect observation, which made it possible to segment the discourse into textual units and analyze the frequencies, co-occurrence, and interaction of the different observed categories. This systematization not only facilitated the detection of regularities within the discourse but also strengthened the analysis of the relationships between technical-tactical dimensions.

As for the vector size and its angle, these determine the intensity of the relationships between the focal behavior and the paired behaviors. From an applied perspective, Quadrant I reflects the importance of studying opponents and adjusting the behavioral scheme. Interviewee 1 stated: “I had a technical-tactical scheme for right- and left-handed opponents, and I studied my rivals” (A1SIPRETEC). Interviewee 5 emphasized that in high-level competition not all matches are won the same way: “You must know who you have in front of you and when to be proactive or cautious” (A1SIPRETEC). He also stressed the need to make strategic adaptations without abandoning one’s own style. Regarding technical-tactical predominance by weight, sex, or age, several interviewees agreed on its influence, albeit with exceptions. For example, Interviewee 4 (female) noted differences by weight and age, while Interviewee 5 (male) pointed out that female and male judo are sometimes similar.

On the relationship between technical-tactical behaviors and specific situations, Interviewee 2 (male) said: “I always ask: what is the opponent doing? And we adjust the match accordingly.” When at a disadvantage, he would opt for previously successful tactics, avoiding unfavorable ones (A1SIPRETEC). He also highlighted the relevance of all time periods of the match, especially the first, for exploration, and the fourth, where fatigue affects performance (H3TODPER).

Regarding kumikata, several interviewees agreed on the importance of mastering it to execute effective techniques. For instance, Interviewee 4 (female) considered it essential to impose the grip (J1IMPAG), while Interviewee 2 (male) noted that dominating the grip facilitates controlling the match (J1IMPAG). In groundwork situations, Interviewee 2 (male) suggested acting from comfortable and individualized positions, while Interviewee 3 (female) preferred working from positions that allowed for both defense and attack (J3IMOADAP).

In Quadrant II, the use of feints and deceptions (E1AMG) was highlighted. Interviewee 2 (male) considered that they must generate real threat to the opponent, while others viewed them as effective tools to provoke reactions. Interviewee 8 (male) noted that the higher the level of deception, the lower the possibility that the opponent will decipher it.

Quadrant III underlined the need to train transitions between standing and groundwork (K1TRANSPS). Interviewee 1 (female) observed that insecurity in groundwork conditions performance in standing judo (L4POSRECEJ). Interviewee 5 (male) stated that matches are often won through an effective transition to groundwork (K1TRANSPS), such as immobilizations or strangles. Interviewee 6 (male) stressed the importance of chaining techniques in groundwork and adapting positions to maximize effectiveness (L4POSRECEJ).

In Quadrant IV, the influence of technical role models and fashions imposed by rule changes (B1EXMOD) was mentioned. Interviewee 5 (male) stressed the importance of working in specific areas of the tatami to avoid penalties or loss of balance (G1DIFZON). Regarding activation, interviewees considered the opening and closing minutes of the match to be key, with the latter being the most critical due to accumulated fatigue (H1INFINPER).

Conclusions

The main conclusions of this study can be summarized in two:

- The variability in the responses reflects the diverse experiences and roles of the interviewees—judokas, strength and conditioning coaches, judo instructors in the Bachelor’s Degree in Physical Activity and Sports Sciences, and coaches—which provides unique perspectives.

- The analysis showed that adaptive behaviors and knowledge of the opponent are essential for success. Patterns vary according to context and highlight the strategic use of feints, the importance of mastering transitions and areas of the tatami, and the influence of technical role models.

Limitations

Among the main limitations of the study is the dependence on the original communicative context, since the data analyzed were not generated under conditions controlled by the researcher. This may hinder the full interpretation of the content due to the lack of all contextual information. Furthermore, this type of observation entails a greater risk of cognitive interference during the segmentation and coding of textual units, which may introduce some degree of subjectivity despite the control mechanisms applied.

Future Lines of Research

In the near future, judo researchers could propose studies aimed at understanding the influence of the dimensions suggested in this study on success in amateur, grassroots, and elite women’s and men’s judo. In this regard, studying aspects such as: (i) the existence of technical predominance in standing and groundwork judo situations according to weight category, sex, and/or age; (ii) the existence of tactical predominance in standing and groundwork judo situations according to weight category, sex, and/or age; (iii) the existence of optimal working areas within the tatami; or (iv) the existence of possible psychological, physical, technical/tactical profiles that a judoka must have to achieve success, will help expand the scientific corpus on this subject while simultaneously increasing the potential performance of competitors.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Spanish Government project LINCE PLUS: Multimodal platform for data integration, synchronization and analysis in physical activity and sport [PID2024-15605NB-l00] (2025-2027) (Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, Agencia Estatal de Investigación y Unión Europea).

References

[1] Alcover, C., Mairena, M. Á., Mezzatesta, M., Elias, N., Díez-Juan, M., Balañá, G., González-Rodríguez, M., Rodríguez-Medina, J. Anguera, M.T. & Arias-Pujol, E. (2019). Mixed methods approach to describe social interaction during a group intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1158. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01158

[2] Alvarado-Alvarez, C., Armadans, I., Parada, M. J., & Anguera, M. T. (2021). Unraveling the role of shared vision and trust in constructive conflict management of family firms. An empirical study from a mixed methods approach. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 629730. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.629730

[3] Anguera, M. T. (1979). Observational Typology. Quality y Quantity. European-American Journal of Methodology, 13(6), 449–484. doi.org/10.1007/BF00222999

[4] Anguera, M. T. (2003). La metodología selectiva en la Psicología del Deporte In A. Hernández Mendo (Coord.), Psicología del Deporte (Vol. 2). Metodología (pp. 74–96). Buenos Aires: Efdeportes.

[5] Anguera, M. T. (2020). Is it possible to perform “liquefying” actions in conversational analysis? The detection of structures in indirect observations. In: Hunyadi, L., Szekrényes, I. (eds). The Temporal Structure of Multimodal Communication. Intelligent Systems Reference Library (Vol 164). Springer, Cham. doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22895-8_3

[6] Anguera, M. T., Blanco-Villaseñor, A., Hernández-Mendo, A., & Losada, J. L. (2011). Diseños observacionales: ajuste y aplicación en Psicología del Deporte. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 11(2), 63–76.

[7] Anguera, M. T., & Hernández-Mendo, A. (2016). Avances en estudios observacionales de Ciencias del Deporte desde los mixed methods. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 16(1), 17-30. Retrieved from revistas.um.es/cpd/article/view/254261

[8] Anguera, M. T., Camerino, O., Castañer, M., Sánchez-Algarra, P., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2017). The specificity of observational studies in physical activity and sports sciences: moving forward in mixed methods research and proposals for achieving quantitative and qualitative symmetry. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 2196. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02196

[9] Anguera, M. T., Portell, M., Chacón-Moscoso, S., & Sanduvete-Chaves, S. (2018). Indirect observation in everyday contexts: concepts and methodological guidelines within a mixed methods framework. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 13. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00013

[10] Anguera, M. T., Portell, M., Hernández-Mendo, A., Sánchez-Algarra, P., & Jonsson, G. K. (2021). Diachronic analysis of qualitative data. In A. J. Onwuegbuzie, & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Routledge Reviewer’s Guide to Mixed Methods Analysis (125-138). Taylor and Francis AS. doi.org/10.4324/9780203729434-12

[11] Arias-Pujol, E., & Anguera, M. T. (2020). A mixed methods framework for psychoanalytic group therapy: from qualitative records to a quantitative approach using t-pattern, lag sequential, and polar coordinate analyses. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1922. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01922

[12] Bakeman, R., y Quera, V. (2011). Sequential analysis y observational methods for the behavioral sciences. Cambridge, Engly: Cambridge University Press.

[13] Barbero, J.R., Lapresa, D., Arana, J. & Anguera, M.T. (2024). Sequential analysis of the interaction between kicker and goalkeeper in penalty kicks. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 24(3), 208–224). doi.org/10.6018/cpd.622011

[14] Castañer, M., Camerino, O. y Anguera, M. T. (2013). Mixed Methods in the Research of Sciences of Physical Activity and Sport. Apunts Educación Física y Deporte, 112, 31–36. dx.doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2013/2).112.01

[15] Caprara, M., & Argilaga, M. T. A. (2019). Observación sistemática. In Evaluación psicológica: proceso, técnicas y aplicaciones en áreas y contextos (pp. 249-277). Sanz y Torres.

[16] Cohen, J. A. (1960). Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

[17] Del Giacco, L., Anguera, M. T., & Salcuni, S. (2020). The action of verbal and non-verbal communication in the therapeutic alliance construction: a mixed methods approach to assess the initial interactions with depressed patients. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 234. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00234

[18] Franchini, E., Takito, M. Y., Kiss, M., y Strerkowicz, S. (2005). Physical fitness and anthropometrical differences between elite and non-elite judo players. Biology of sport, 22(4), 315.

[19] Gamero-Castillero, J. A., Quiñones-Rodríguez, Y., Apollaro, G., Hernández-Mendo, A., Morales-Sánchez, V., & Falcó, C. (2022). Application of the Polar coordinate technique in the study of Technical-Tactical scoring actions in Taekwondo. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4, 877502. doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.877502

[20] García-Fariña, A., Jiménez-Jiménez, F., & Anguera, M. T. (2018). Observation of communication by physical education teachers: detecting patterns in verbal behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 334.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00334

[21] Hernández-Mendo, A., López, J. A., Castellano, J., Morales-Sánchez, V., y Pastrana, J. L. (2012). Hoisan 1.2: Programa informático para uso en Metodología Observacional. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte, 12(1), 55-78. Retrieved from revistas.um.es/cpd/article/view/162641

[22] Iván-Baragaño, I., Ardá, A., Anguera, M. T., Losada, J. L., & Maneiro, R. (2023a). Future horizons in the analysis of technical-tactical performance in women’s football: a Mixed Methods approach to the analysis of in-depth interviews with professional coaches and players. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1128549. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1128549

[23] Iván-Baragaño, I., Ardá, A., Losada, J.L. & Maneiro R. (2023b). Influence of quality of opposition in the creation of goal scoring opportunities in female football. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 154, 71-82.doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2023/4).154.07

[24] Iván-Baragaño, I., Maneiro, R., Losada, J. L., & Ardá, A. (2021). Multivariate analysis of the offensive phase in high-performance Women’s soccer: a mixed methods study. Sustainability, 13(11), 6379. doi.org/10.3390/su13116379

[25] Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage publications. doi.org/10.4135/9781071878781

[26] Landis, J. R. (1977). The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics.

[27] Lapresa, D., Otero, A., Arana, J., Álvarez, I., and Anguera, M. T. (2021). Concordancia consensuada en metodología observacional: efectos del tamaño del grupo en el tiempo y la calidad del registro [Consensual agreement in observational methodology: effects of group size over time and quality of the registry]. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte 21, 47–58. doi.org/10.6018/cpd.467701

[28] Maneiro, R. (2021). Aproximación mixed methods en deportes colectivos desde técnicas estadísticas robustas [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Universidad de Barcelona.

[29] Nunes, H., Iglesias, X., Del Giacco, L., & Anguera, M. T. (2022). The pick-and-roll in basketball from deep interviews of elite coaches: a mixed method approach from polar coordinate analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 801100. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.801100

[30] Portell, M., Anguera, M. T., Chacón Moscoso, S., & Sanduvete Chaves, S. (2015). Guidelines for reporting evaluations based on observational methodology. Psicothema, 27(3), 283–289. doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2014.276

[31] Sarmento, H., Anguera, M. T., Pereira, A., Marques, A., Campaniço, J., & Leitão, J. (2014). Patterns of play in the counterattack of elite football teams-A mixed method approach. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 14(2), 411–427. doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2014.11868731

[32] Sarmento, H., Clemente, F. M., Gonçalves, E., Harper, L. D., Dias, D., & Figueiredo, A. (2020). Analysis of the offensive process of AS Monaco professional soccer team: A mixed-method approach. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 133, 109676. doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109676

[33] Soto, A., Camerino, O., Iglesias, X., Anguera, M. T., & Castañer, M. (2019). LINCE PLUS: Research software for behavior video analysis. Apunts Educación Física y Deporte (137), 149-153.

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: February 3, 2025

Accepted: June 2, 2025

Published: October 1, 2025

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en