A proposal for load monitoring in basketball based on the joint use of four low-cost tools

*Corresponding author: Daniel Lapresa daniel.lapresa@unirioja.es

Cite this article

Molina, R., Lapresa, D., Arana, J., Álvarez-Marín, I. & Salazar, H. (2025). A proposal for load monitoring in basketball based on the joint use of four low-cost tools. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 160, 26-34. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2025/2).160.04

Abstract

In this article, conducted within a professional basketball club that simultaneously played in the ACB League and the Basketball Champions League, the joint use of four low-cost tools for load monitoring is presented: Integral analysis system of training tasks (SIATE), session rating of perception exertion (sRPE), heart rate monitoring (TRIMP) and the athlete’s subjective perception of well-being (Wellness questionnaire). Using a structural equation modeling approach, we analyse the relationships generated between the results obtained with each of these tools (the scores of the seven players who met the inclusion criteria over the 31 weeks of the season), determining which variables can predict the objective internal load scores obtained from TRIMP corresponding to the day of highest load of the week. This is the first study that relates these four low-cost load monitoring tools. Using a structural equation model, in which all relationships were statistically significant, the relationship between the scores obtained in TRIMP and SIATE, sRPE and Wellness variables was verified, which supports the joint use of the four proposed low-cost tools.

Introduction

Sport performance is the result of a complex interaction between factors that influence an athlete’s ability to reach their full potential. The control of training loads is a fundamental component in the optimisation of performance and the prevention of injuries in athletes of all disciplines and skill levels. The vast majority of trainers do not have access to inertial or tracking devices (GPS/LPS) due to their high cost. In this context, the need to explore and develop low-cost tools that can provide accurate and reliable data on individual and squad fitness arises.

In this article, the joint use of four low-cost tools for load control is presented: the Integrated System for the Analysis of Training Tasks (SIATE), the session Rate of Perceived Exertion (sRPE), heart rate monitoring (TRIMP method) and the subjective perception of the state of well-being by the athlete (Wellness questionnaire).

SIATE (Ibáñez et al., 2016) was used to monitor the external load (objective aspect). SIATE has its origin in the load monitoring proposal made by Coque (2008, 2009) for the Spanish national senior men’s basketball team. It is a monitoring system characterised by being universal, standardisable, modular and flexible (Ibáñez et al., 2016). Reina et al. (2019) demonstrated the close correlation between external load control using SIATE and data analysed using tracking devices (objective external load), which included variables such as accelerations, decelerations, distance travelled and Player Load, calculated as the square root of the sum of the instantaneous rate of change in acceleration in the three planes of motion (Bredt, et al., 2020).

For the monitoring of the internal load (subjective aspect) and based on the Borg scale or Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE), Foster’s (2001) index or session Rate of Perceived Exertion (sRPE) was used, which was obtained by multiplying the player’s RPE by the training time. It is a reliable tool for monitoring and controlling training loads, having been found to be strongly correlated with external load variables (Casamichana et al., 2013; Clemente et al., 2019; Gallo et al., 2015; Moreira et al., 2012; Svilar et al., 2018). Despite their subjective nature, the RPE and sRPE variables are more consistent against both acute and chronic loads and show a greater sensitivity than other objective measures such as blood creatine kinase levels (Saw et al., 2015) or heart rate response during training (Moussa et al., 2019).

Heart rate proved to be a gold standard for monitoring objective internal load (Manzi et al., 2010) by providing real-time information on the body’s physiological response and thus offering instant feedback on the athlete’s cardiovascular response. In the present study, the Training Impulse (TRIMP) (Bannister et al., 1991), as an indicator of the load obtained from the heart rate, was used to quantify the load accumulated by a player during a training session. TRIMP is the result of multiplying the duration of the exercise by its intensity (expressed as a percentage of the maximum heart rate). The general formula for this calculation is: TRIMP = ∑ni=1(Durationi x Intensityi x e0.64 x Intensityi), where Duration is the duration of the excercise; Intensity is the intensity of the excercise expressed as a percentage of the individual’s maximum heart rate; and e is the base of the natural logarithm (2.71828). Finally, the intensity is associated with a weighting factor that varies according to the authors consulted (Foster et al., 2001; Puente et al., 2017 ; Saldanha et al., 2017; Torres-Ronda et al., 2016).

Lastly the Wellness questionnaire, which has its origins in the Hooper y Mackinnon index (1995), was used. This questionnaire provides information on five variables: sleep, stress, motivation, fatigue level and illness. The development of a well-being passport derived from multiple well-being measures is a tool to determine the level of performance that can be expected from the athlete (Clemente et al, 2017). Their easy implementation into daily routines (just 1 minute) allows the use of Wellness questionnaires as a monitoring tool (Jones et al., 2017). Well-being values are used as prescriptive parameters of external load given the negative impact of low ratings on external load (Gallo et al., 2015). The resulting reduction in training volume and frequency (tapering) will lead to a decrease in internal load, which will result in an increase in the assessment of well-being (Botonis et al., 2019).

The combined use of the data collected with the low-cost monitoring tools that make up this load monitoring proposal enables informed decision making. Thus, the objectives of the present work are: a) to present a proposal for monitoring loads in basketball consisting of the joint use of four low-cost tools that allow coaches and trainers who cannot afford expensive tracking devices to optimise the control and management of sporting performance; and b) to determine which variables can predict the objective internal load scores obtained from TRIMP, relating to the session with the highest load of the week, analysing the results obtained by each of the low-cost tools that constitute the load monitoring proposal.

Methodology

Participants

A non-experimental cross-sectional comparative study was carried out using a repeated measures design. The data supporting this study was collected in a professional men’s basketball club which, in the season under study, played two competitions simultaneously: the ACB League (Spanish Basketball Association) at national level and the Basketball Champions League at international level. The squad, composed of 20 players, held 232 group training sessions and played a total of 48 official competition matches. The inclusion criteria to be part of the sample that support the results of this article were similar to those used in this type of work (Clemente et al., 2019): a) presenting of medical authorisation to practice in a professional context; b) having completed 80% of the mesocycles of the season; and c) having completed 80% of the sessions of the corresponding mesocycle. Those participants from the squad who did not meet these inclusion criteria were excluded, so that the final sample consisted of the seven players who met all the pre-set requirements. We worked with the scores of these players in the session with the highest weekly load in the 31 weeks (microcycles) of the season, which means 217 scores for each low-cost tool, with which a structural equation model can be conveniently developed (Wolf et al., 2013).

This work was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. It has the authorisation of the club and the informed consent of the participants, as well as the approval of the Research Ethics Committee of the University of La Rioja (file no. 76529).

Instruments and procedure

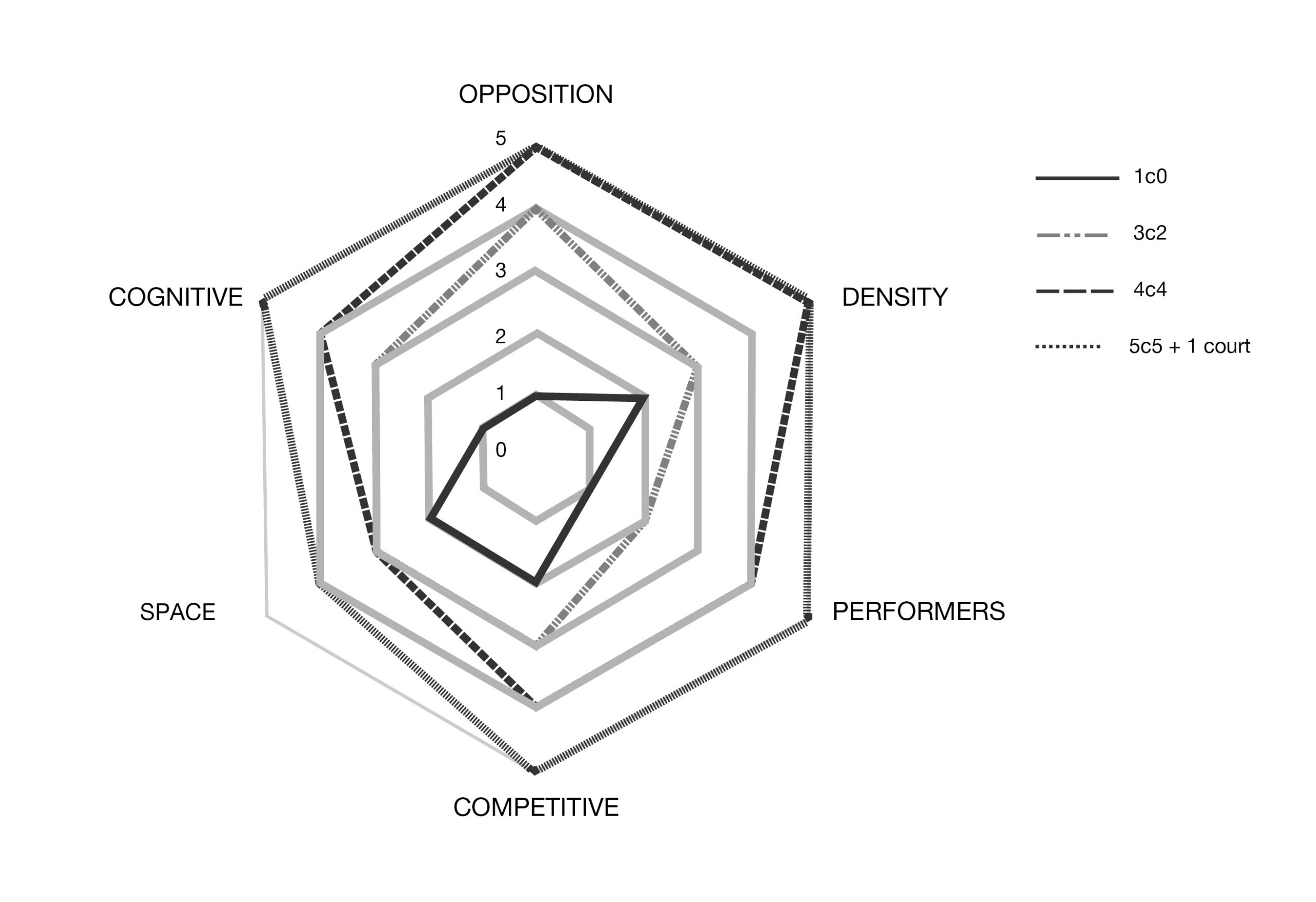

In the proposed use of SIATE, the tasks performed and the useful time spent on each task were recorded during all the group’s training sessions. This tool consists of six “primary” variables: degree of opposition, task density, number of simultaneous performers, competitive factor, game space and cognitive involvement. Each of the tasks is scored according to the six dimensions mentioned above, with a maximum score of 5 points and a minimum score of 1 point (see Table 1 and Figure 1).

“Secondary” variables are derived from these “primary” variables, such as the task load, obtained from the sum of the value assigned to each of the six primary parameters (ranging from 5 to 30 points) and the task load per useful practice time, the result of which was expressed in arbitrary units (AU). The latter parameter more accurately reflects the actual task load (Reina et al., 2019; Fuster et al., 2021). As for the SIATE thresholds, the theoretical maximum load was taken as a reference, which corresponds to that of the match or competition (García et al., 2022; Torres-Ronda et al., 2016), where the useful playing time in an official basketball match is forty minutes and the score assigned to the “5×5 continuous” task is the highest possible with 30 points (1200 AU). With this reference, four types of session were established according to the load: low load sessions (recovery), corresponding to values below 50% of the match load, with loads below 600 AU; medium load sessions (maintenance), with loads between 50-69% of the match load, between 600-799 AU; high load sessions (development), corresponding to a load between 70-89% of competition, between 800-999 AU; and competitive sessions, between 1000-1200 AU.

Each player’s RPE data was collected during all training sessions in the 15–45-minute post-training window using the Teambuildr LLC platform, although there are other free tools available for data collection, such as Google questionnaire, Survey Monkey or Pollfish, and even the WhatsApp application. Thanks to this tool, each player answered the questions: a) How hard was the session on a muscular level?; and b) How hard was the session on a cardiovascular level? Taking into account the following rating scale: extremely light = 1, very light = 2, light = 3-4, moderate = 5-6, intense = 7-8, very intense = 9, and maximum effort = 10. The value obtained is expressed in AU. The RPE is the result of the average of muscle RPE and cardiovascular RPE. For the computation of the sRPE, the useful training time expressed in minutes, taking into account substitutions and not including the initial and final part of the session (Reina et al., 2019; Scanlan et al., 2014), was multiplied by the total RPE of the player (see Table 2).

Heart rate recording, collected during the highest weekly load training session according to SIATE, was conducted using Polar HR10 devices, linked to Polar Team computer programme (v. 1.9.1) installed and active on a tablet. In this load monitoring proposal, TRIMP was calculated by adding the values obtained by multiplying the time (in minutes) that the player spent in each training zone by the associated weighting coefficient. Following the proposal of Stagno et al. (2007) during our intervention (see Table 3), a different weighting coefficient was assigned to each of the five zones of cardiovascular compromise: Z1, between 65-71% of HRmax (weighting coefficient = 1.25); Z2, between 72-78% of HRmax (1.71); Z3, from 79-85% of HRmax (2.54); Z4, from 86-92% of HRmax (coefficient 3.61); and Z5, from 93-100% of HRmax (5.16). These heart rate zones were established on an individual basis according to the parameters of the stress test performed at the medical examination at the beginning of the season.

Regarding the application of the Wellness questionnaire, the athletes completed daily, using the digital platform Teambuildr and up to one hour before the start of the session, a questionnaire with five dimensions: a) Energy: how are you in terms of energy?; b) Muscular: how are you in terms of muscle?; c) Injury: do you feel limited by injury or illness?; d) Mood: what is your level of stress or motivation?; and e) Sleep: how would you rate your sleep? The lowest response value, equal to 1, is linked to the factor that restricts performance, while the highest, equal to 10, is assigned to the factor that benefits performance. The total Wellness score (see Table 4) corresponds to the sum of the scores obtained in each of the dimensions, with a maximum of 50 points and a minimum of 5.

Data analysis

In order to satisfy the objective of analysing the relationships generated between the results obtained by each of the low-cost tools that constitute the load monitoring proposal, determining which variables can predict the TRIMP scores in the highest load session of the week, the relationship between the TRIMP scores and the Wellness, SIATE, sRPE and RPE variables was calculated using Structural Equation Models and Pearson correlations. Following Cohen’s criteria (Gignac & Szodorai, 2016), values r = .10, r = .30 and r = .50 were considered small, medium and large in magnitude, respectively. Correlation values with an associated probability less than or equal to .05 were qualified as statistically significant.

In the analysis of the predictive model, the Robust Weighted Least Squares estimator and Chi-square values were used. Model adequacy was estimated using the following goodness-of-fit indices: comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) (Schreider et al., 2006). A good model fit is considered to exist if the RMSEA value is less than .05, the SRMR less than .08 and the CFI and TLI indices greater than .95 (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

The data have been entered into a log sheet (Microsoft Excel v15) customised by the researchers. The software SPSS 28.0 and MPLUS 7.2 were used for data analysis.

Results

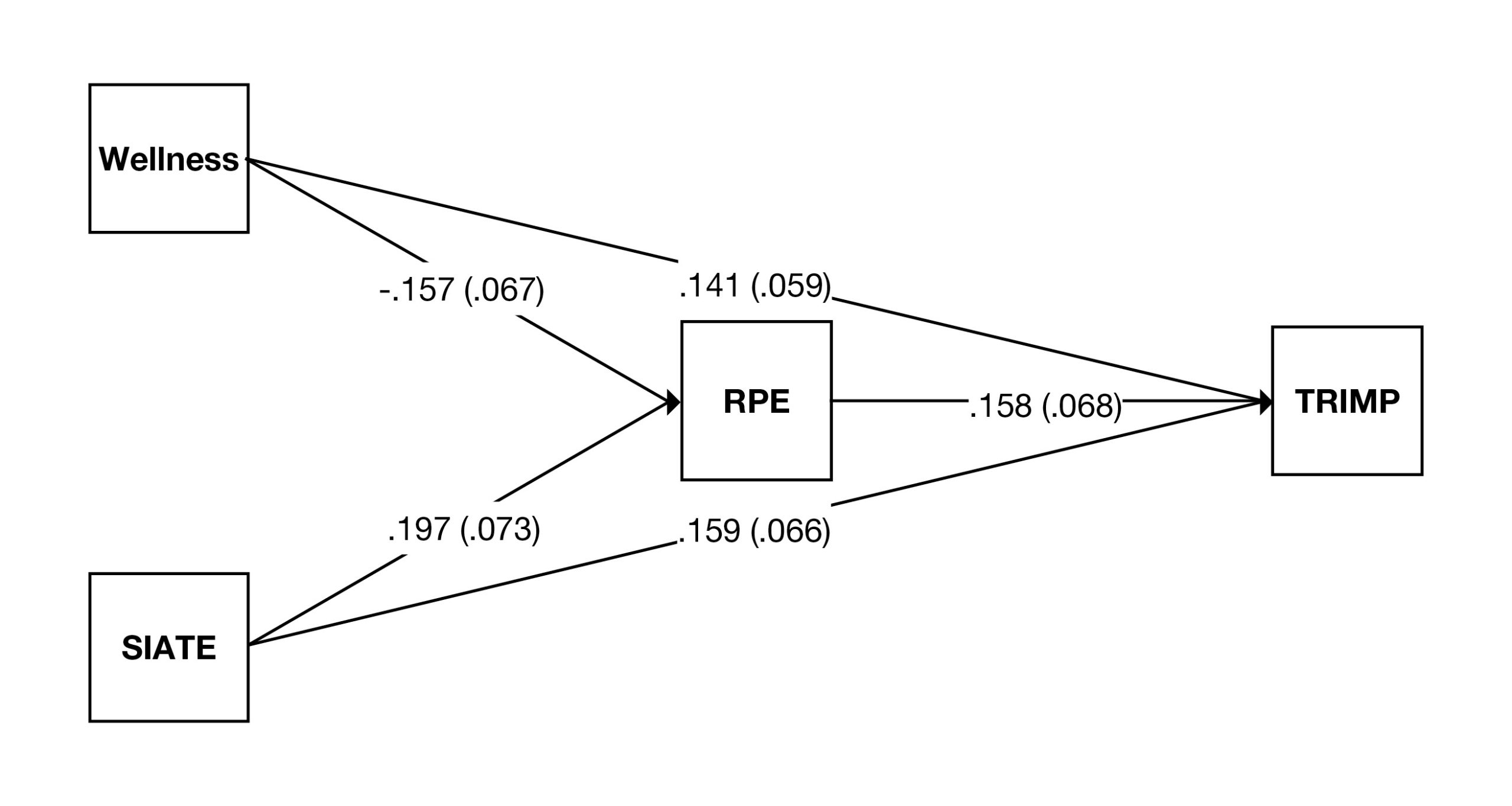

Initially, an attempt was made to perform a structural equation model incorporating the relationship between TRIMP scores (Mean = 151.43; Standard deviation = 41.38) and the Wellness (Mean = 40.70; Standard deviation = 3.20), sRPE (Mean = 639.62; Standard deviation = 153.77) and SIATE variables (Mean = 2015.29; Standard deviation = 435.60) but no significant correlations were obtained, except for the association between sRPE and SIATE (r = .467; p < .001). However, when incorporating the Wellness, RPE (Mean = 6.95; Standard deviation = 1.23) and SIATE variables, statistically significant relationships were obtained between all related variables. The CFI and TLI fit indices of this Structural Equation Model are both equal to 1. The RMSEA value is less than .001 and the SRMR value is .056. These values corroborated the good fit of the model presented in Figure 2.

The scores of the Wellness questionnaire (.141) and the Integral System of Analysis for Training Tasks (SIATE) (.159), directly influence the objective internal load values collected through the TRIMP as an indicator of the cardiovascular stress that the task exerts on the player.

TRIMP is also indirectly modulated by scores on the RPE variable. The effect of SIATE on TRIMP, mediated by RPE, is obtained by multiplying the correlation coefficients of the relationship mediated by RPE and adding the direct coefficient: On the other hand, the effect of Wellness on

TRIMP, mediated by RPE, is: (–.157 x .158) + .141 = .116. The negative correlation between Wellness and RPE reflects the fact that the higher the sRPE score, the harder the session and therefore the lower the perceived well-being (score on the Wellness questionnaire).

Discussion

The management of training loads is essential to improve performance and avoid injuries in athletes of any level and discipline. Most coaches and trainers do not have access to tracking devices due to their high cost. This article satisfies, first of all, the objective of presenting a load monitoring proposal consisting of the joint use of four low-cost tools that optimise the control and management of sports performance in basketball. In this regard, SIATE, sRPE and Wellness are variables that can be implemented in an Excel-type record sheet, which facilitates their use in all types of sport contexts. TRIMP is collected by heart rate sensors whose associated cost is affordable for the vast majority of technicians and sports organisations.

The use of the SIATE control tool, the task load per useful practice time expressed in minutes, for the monitoring of the external load (objective aspect), allows the monitoring of the real load of the tasks developed in the training session and allows its adaptation to adjust to the programming, keeping within the limits established for each type of session: regenerative (< 50%), maintenance (50-69%), development (70-89%), and competition (90-100%).

For the monitoring of the internal load (subjective aspect), the session Rate of Perceived Exertion (sRPE) was, taking into account the Acute: Chronic Workout Ratio model (ACWR) (Hulin et al., 2016), according to which the risk of injury increases when the acute load fluctuates significantly. Weekly sRPE values can vary from 2000 to 5000 AU depending on the competitive density, number of sessions, duration of sessions, number of players, etc. (Piedra et al., 2021). A 10% weekly increase in RPE or sRPE alone can explain 40% of the injuries occurring during the following week (Piggott et al., 2009). It is therefore recommended that load planning is developed by comparing the sum (individual or collective) of sRPE values between consecutive microcycles and keeping the inter-weekly variability of sRPE values below the theoretical 10% (Gabbett, 2016).

The objective internal load monitoring by heart rate was performed in the highest load session of the week according to SIATE, which involves exposing the player to loads similar to those of competition (Berkelmans et al., 2018), and implies an optimisation in the management of the team and players’ sporting performance, reducing the effort required for data collection (Foster et al., 2017). The TRIMP was calculated by adding the values obtained by multiplying the time (in minutes) that the player spent in each training zone by the associated weighting coefficient. The analysis of the TRIMP data focused on a comparison of post-training values: a) intra-session between players; and b) inter-session for the same player. When a player’s values deviate from those of the rest of the group for several consecutive sessions, programming adjustments are considered appropriate (Buchheit & Laursen 2013).

Regarding the well-being questionnaire, and taking into account that the performance of players with low scores in the Wellness questionnaire can be negatively affected (Gallo et al., 2017), special attention is paid (Govus et al., 2018) to the questionnaires that have: a) less than 25 total points, and b) two or more parameters below 5 points. When any of the situations described above arose, a joint assessment was made by the staff of the player’s availability for the work session and the training load was adjusted to reduce the risk of fatigue or injury. And the fact is that, irrespective of the number of matches played during the week, tapering strategies have been shown to increase the Wellness profile on match days and reduce RPE and sRPE values (Manzi et al., 2010)

The second objective of the article focuses on analysing the relationships that are generated, in the session with the highest load of the week, between the results obtained by each of the low-cost tools that constitute the load monitoring proposal, determining which variables can predict the objective internal load scores obtained from the TRIMP.

For the development of the structural equation presented in the article, the first variable whose mediating effect between Wellness and SIATE and TRIMP scores analysed was sRPE, but when it was observed that the resulting solution did not present adequate goodness-of-fit indices, it was decided to replace it with RPE. This could be due to the fact that the scores in the sRPE are those corresponding to the RPE, but multiplied by the training time (Foster, 2001), which increases the range of scores to be analysed and modifies the value of the correlations obtained in the model.

It is noteworthy to mention that all the relationships shown in the structural equation model (Figure 2) were statistically significant, despite the small sample size, which clearly shows the relationship between the TRIMP scores and the SIATE, RPE and Wellness variables. However, one of the limitations of this study is the low correlation values obtained between the variables that make up the Structural Equation Model. One of the reasons is the small sample size which decreases the power of contrast (ability of the test to find high correlations) of the tests performed. It is our intention in future work to replicate the study with larger sample sizes to see if the amount of correlation increases in this case. Although the correlations are not as numerous as the researchers would have liked, this does not detract from their practical significance. This

is the first paper linking these four low-cost tools and the theoretical or substantive implications of the fact that all the relationships shown in the structural equation model were statistically significant should be highlighted and considered in the overall research design.

It should be added that the results of the present study reinforce those obtained in studies that have not found, in basketball, a relationship between some of the variables analysed : sRPE and TRIMP (Aoki et al., 2017; Manzi et al., 2010); and sRPE and Wellness (Clemente et al., 2019; Edwards et al., 2018). It also supports the relationship found between the data collected through the SIATE tool and other objective internal load data such as heart rate or collected by inertial devices (Gómez-Carmona et al., 2019; Reina et al., 2019). The joint use of the four proposed low-cost tools is thus validated.

Conclusion

Two objectives were pursued in this study, which was carried out in the context of a professional basketball club. The first consisted of presenting a proposal for monitoring loads in basketball made up of the joint use of four low-cost tools: the Integrated System for the Analysis of Training Tasks (SIATE), the subjective perception of the effort of the session (sRPE), the monitoring of heart rate (TRIMP) and the subjective perception of the state of well-being of the athlete (Wellness questionnaire). This proposal can allow coaches and trainers who cannot afford expensive tracking devices to optimise the control and management of the sporting performance of their team and players.

The second objective was to analyse the relationships generated, in the session with the highest load of the week, between the results obtained by each of the low-cost tools that make up the load monitoring proposal, determining, by means of a structural equation model, which variables can predict the objective internal load scores obtained from the TRIMP. Although the amount of correlations is not high, since the sample size reduces the power of contrast of the tests carried out, the relationship between the scores obtained in the TRIMP and the SIATE, RPE and Wellness variables was confirmed, a fact that supports the proposal for the joint use of these four low-cost load monitoring tools and recommends further research in this area.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the project Integration between observational and external sensor data: Evolution of the LINCE PLUS software and development of the mobile application for the optimisation of sport and health-enhancing physical activity [EXP_74847] (2023). Ministry of Culture and Sport, High Council for Sport and European Union.

References

[1] Aoki, M.S., Ronda, L.T., Marcelino, P.R., Drago, G., Carling, C., Bradley, P.S., & Moreira, A. (2017). Monitoring training loads in professional basketball players engaged in a periodized training program. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 31(2), 348–358. doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001507

[2] Bannister, E.W. (1991). Modelling athletic performance. In H.J. Green, J.D. McDougal, & H. Wenger (Eds.), Physiological testing of elite athletes (pp. 403–424). HumanKinetics.

[3] Berkelmans, D. M., Dalbo, V. J., Kean, C. O., Milanović, Z., Stojanović, E., Stojiljković, N., & Scanlan, A. T. (2018). Heart rate monitoring in basketball: Applications, player responses, and practical recommendations. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 32(8), 2383–2399. doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002194

[4] Botonis, P.G., Toubekis, A.G., & Platanou, T.I. (2019). Training loads, wellness and performance before and during tapering for a Water-Polo tournament. Journal of Human Kinetics, 66(1), 131–141. doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2018-0053

[5] Buchheit, M., & Laursen, P.B. (2013). High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle: Part I: cardiopulmonary emphasis. Sports Medicine, 43(5), 313–338. doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0029-x

[6] Bredt, S.D.G.T., Chagas, M.H., Peixoto, G.H., Menzel, H.J., & de Andrade, A.G.P. (2020). Understanding player load: Meanings and limitations. Journal of Human Kinetics, 71(1), 5–9. doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2019-0072

[7] Casamichana, D., Castellano, J., Calleja-Gonzalez, J., San Román, J., & Castagna, C. (2013). Relationship between indicators of training load in soccer players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 27(2), 369–374. doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182548af1

[8] Clemente, F. M., Mendes, B., Nikolaidis, P.T., Calvete, F., Carriço, S., & Owen, A.L. (2017). Internal training load and its longitudinal relationship with seasonal player wellness in elite professional soccer. Physiology & Behavior, 179, 262–267. doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.06.021

[9] Clemente, F.M., Mendes, B., Bredt, S.D.G.T., Praça, G.M., Silvério, A., Carriço, S., & Duarte, E. (2019). Perceived training load, muscle soreness, stress, fatigue, and sleep quality in professional basketball: a full season study. Journal of Human Kinetics, 67(1), 199–207. doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2019-0002

[10] Coque, N. (2008). Valoración subjetiva de la carga del entrenamiento técnico-táctico. Una aplicación práctica (I). Clínic, Revista Técnica de Baloncesto 21(81), 39–43.

[11] Coque, N. (2009). Valoración subjetiva de la carga del entrenamiento técnico-táctico. Una aplicación práctica (II). Clínic, Revista Técnica de Baloncesto 22(82), 42–45.

[12] Edwards, T., Spiteri, T., Piggott, B., Bonhotal, J., Haff, G.G., & Joyce, C. (2018). Monitoring and managing fatigue in basketball. Sports, 6(1), 19. doi.org/10.3390/sports6010019

[13] Foster, C., Rodriguez-Marroyo, J. A., & De Koning, J. J. (2017). Monitoring training loads: the past, the present, and the future. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 12(s2), 2–8. doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2016-0388

[14] Foster, C., Florhaug, J. A., Franklin, J., Gottschall, L., Hrovatin, L.A., Parker, S., Doleshal, P. & Dodge, C. (2001). A new approach to monitoring exercise training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 15(1), 109–115. doi.org/10.1519/00124278-200102000-00019

[15] Fuster, J., Caparrós, T., & Capdevila, L. (2021). Evaluation of cognitive load in team sports: literature review. PeerJ, 9, e12045. doi.org/10.7717/peerj.12045

[16] Gabbett, T.J. (2016). The training-injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(5), 273–280. doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095788

[17] Gallo, T.F., Cormack, S.J., Gabbett, T.J., & Lorenzen, C.H. (2017). Self-reported wellness profiles of professional Australian football players during the competition phase of the season. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 31(2), 495–502. doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001515

[18] Gallo, T., Cormack, S., Gabbett, T., Williams, M., & Lorenzen, C. (2015). Characteristics impacting on session rating of perceived exertion training load in Australian footballers. Journal of Sports Sciences, 33(5), 467–475. doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.947311

[19] García, F., Schelling, X., Castellano, J., Martín-García, A., Pla, F., & Vázquez-Guerrero, J. (2022). Comparison of the most demanding scenarios during different in-season training sessions and official matches in professional basketball players. Biology of Sport, 39(2), 237–244. doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2022.104064

[20] Gómez-Carmona, C.D., Gamonales Puerto, J.M., Feu Molina, S., & Ibáñez, S.J. (2019). Estudio de la carga interna y externa a través de diferentes instrumentos: un estudio de casos en fútbol formativo (Study of internal and external load by different instruments. a case study in grassroots). Sportis, 5(3), 444–468. doi.org/10.17979/sportis.2019.5.3.5464

[21] Govus, A.D., Coutts, A., Duffield, R., Murray, A., & Fullagar, H. (2018). Relationship between pretraining subjective wellness measures, player load, and rating-of-perceived-exertion training load in American college football. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 13(1), 95–101. doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2016-0714

[22] Hooper, S.L., & Mackinnon, L. T. (1995). Monitoring overtraining in athletes: recommendations. Sports Medicine, 20, 321–327. doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199520050-00003

[23] Hu, L.T., & Bentler, P.M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

[24] Hulin, B.T., Gabbett, T.J., Lawson, D.W., Caputi, P., & Sampson, J.A. (2016). The acute: chronic workload ratio predicts injury: high chronic workload may decrease injury risk in elite rugby league players. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(4), 231–236. doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-094817

[25] Ibáñez, S.J., Feu, S., & Cañadas, M. (2016). Sistema integral para el análisis de las tareas de entrenamiento, SIATE, en deportes de invasión (Integral analysis system of training tasks, SIATE, in invasion games). E-balonmano. com: Revista de Ciencias del Deporte, 12(1), 3–30. ISSN 1885-7019. Disponible en: . Fecha de acceso: XX XX XXX

[26] Jones, C.M., Griffiths, P.C., & Mellalieu, S.D. (2017). Training load and fatigue marker associations with injury and illness: a systematic review of longitudinal studies.

[27] Manzi, V., D’ottavio, S., Impellizzeri, F.M., Chaouachi, A., Chamari, K., & Castagna, C. (2010). Profile of weekly training load in elite male professional basketball players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(5), 1399–1406. doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e3181d7552a

[28] Moreira, A., McGuigan, M. R., Arruda, A. F., Freitas, C. G., & Aoki, M. S. (2012). Monitoring internal load parameters during simulated and official basketball matches. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 26(3), 861–866. doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31822645e9

[29] Moussa, I., Leroy, A., Sauliere, G., Schipman, J., Toussaint, J. F., & Sedeaud, A. (2019). Robust Exponential Decreasing Index (REDI): adaptive and robust method for computing cumulated workload. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 5(1), e000573. doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000573

[30] Piedra, A., Peña, J., & Caparrós, T. (2021). Monitoring training loads in basketball: a narrative review and practical guide for coaches and practitioners. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 43(5), 12–35. doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0000000000000620

[31] Piggott, B., Newton, M.J., & McGuigan, M.R. (2009). The relationship between training load and incidence of injury and illness over a pre-season at an Australian football league club. Journal of Australian Strength and Conditioning, 17(3), 4–17.

[32] Puente, C., Abián-Vicén, J., Areces, F., López, R., & Del Coso, J. (2017). Physical and physiological demands of experienced male basketball players during a competitive game. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 31(4), 956–962. doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001577

[33] Reina, M., Mancha-Triguero, D., García-Santos, D., García-Rubio, J., & Ibáñez, S. J. (2019). Comparación de tres métodos de cuantificación de la carga de entrenamiento en baloncesto (Comparison of three methods of quantifying the training load in basketball). RICYDE. Revista Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte, 15(58), 368–382. doi.org/10.5232/ricyde2019.05805

[34] Saldanha, M., Torres Ronda, L., Rebouças Marcelino, P., Drago, P., Carling, C., Bradley, P. S., & Moreira, A. (2017). Monitoring training loads in professional basketball players engaged in a periodized training programme. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(2), 348–358. doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001507

[35] Saw, A.E., Main, L.C., & Gastin, P.B. (2015). Monitoring athletes through self-report: factors influencing implementation. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 14(1), 137.

[36] Scanlan, A.T., Wen, N., Tucker, P.S., & Dalbo, V.J. (2014). The relationships between internal and external training load models during basketball training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 28(9), 2397–2405. doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000458

[37] Schreider, J.B., Stage, F.K., King, J., Nora, A., & Barlow, E.A. (2006). Reporting structural equation modelling and confirmatory factor analysis results: a review. The Journal of Education Research, 99(6), 323–337. doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

[38] Svilar, L., Castellano, J., & Jukić, I. (2018). Load monitoring system in top-level basketball team: Relationship between external and internal training load. Kinesiology, 50(1), 25–33.

[39] Stagno, K.M., Thatcher, R., & Van Someren, K.A. (2007). A modified TRIMP to quantify the in-season training load of team sport players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(6), 629–634. doi.org/10.1080/02640410600811817

[40] Torres-Ronda, L., Ric, A., Llabres-Torres, I., de Las Heras, B., & i del Alcazar, X.S. (2016). Position-dependent cardiovascular response and time-motion analysis during training drills and friendly matches in elite male basketball players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 30(1), 60–70. doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001043

[41] Wolf, E.J., Harrington, K.M., Clark, S.L., & Miller, M.W. (2013). Sample size requirements for Structural Equation Models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 76(6), 913–934. doi.org/10.1177/0013164413495237

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: 1, July 2024

Accepted: 11, Noviembre 2024

Published: 1, April 2025

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en