Factors that influence the physical and sports participation of adolescent girls: a systematic review

*Corresponding author: Laura Moreno-Vitoria laura.moreno-vitoria@uv.es

Cite this article

Moreno-Vitoria, L., Cabeza-Ruiz, R. & Pellicer-Chenoll, M. (2024). Factors that influence the physical and sports participation of adolescent girls: a systematic review. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 157, 19-30. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2024/3).157.03

Abstract

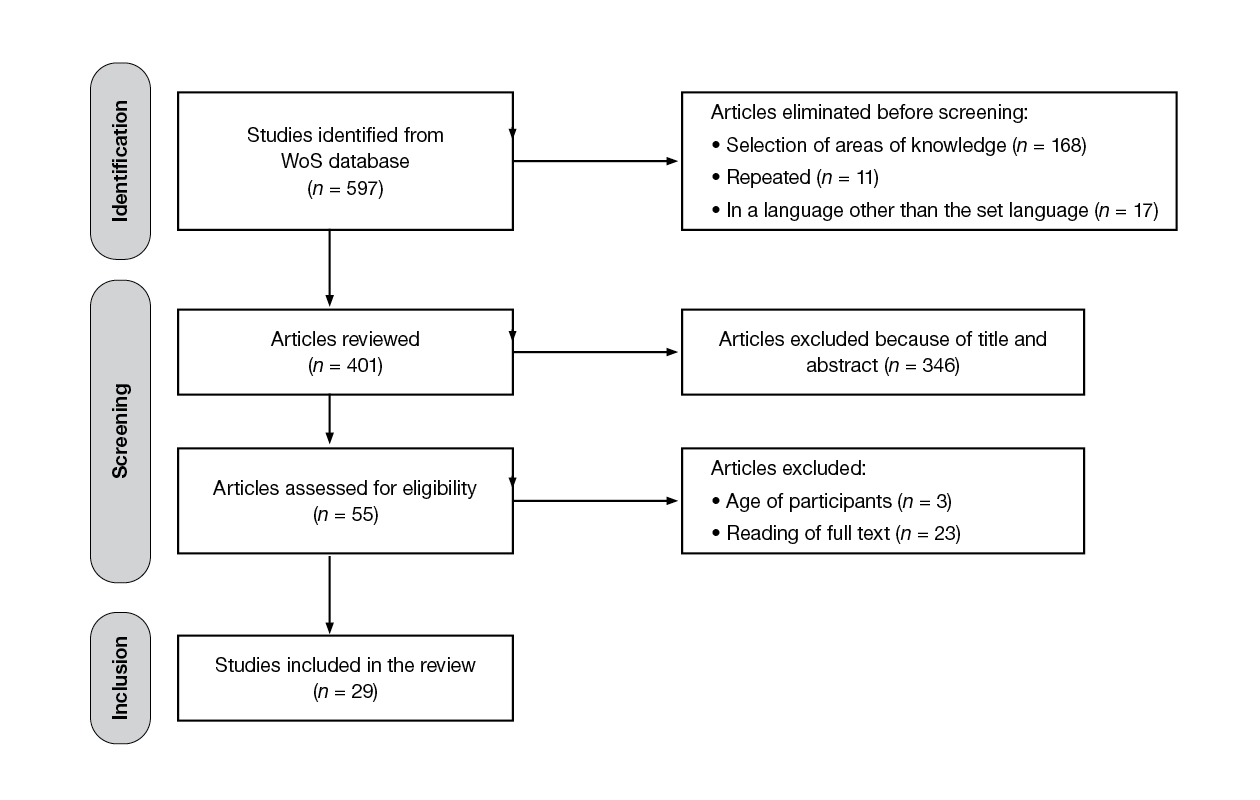

Dropout from physical activity during adolescence is a public health problem, especially for girls. The aim of this study was to analyse the scientific literature in order to identify the factors that encourage sustained participation in physical activity habits and those that lead girls to dropout of sports practice. A search of articles published in the Web of Science database from 2010 to December 2022 was conducted using the keywords: (Physical activity OR Physical exercise OR Sport) AND (Adolesc* OR Children) AND (Female OR Gender OR Girl OR Wom*) AND (Barrier* OR Facilitator*). The PRISMA declaration was adopted for the development of the study. Inclusion criteria were: i) the age of the participants in the studies (up to 21 years of age), ii) the language (Spanish, Catalan or English) and iii) the type of document (article). A total of 597 papers were obtained, from which 29 articles were selected for this review. The results revealed different internal and external factors influencing girls’ dropout or sustained participation in sport activity during adolescence: motivation, self-perception, self-presentation, sport identity, changes during adolescence, sport environment, educational environment, social support, role models and stereotypes. At the end of the study, strategies are proposed to reverse the trend for adolescent girls to dropout of the practice of physical activity and sport.

Introduction

Regular physical activity (PA) is an important protective factor for the prevention and treatment of non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes and several types of cancer (WHO, 2020a). In addition to the benefits it provides for physical health, its effect on academic and cognitive performance has been evidenced (Chacón-Cuberos et al., 2020), proving beneficial for maintaining mental health and preventing cognitive decline and symptoms of depression and anxiety, and contributing to general well-being. The WHO guidelines on PA and sedentary habits (2020a) indicate that, during adolescence, an average of at least 60 minutes of PA should be carried out daily, including vigorous-intensity aerobic activities and activities that strengthen the musculoskeletal system at least 3 days a week. However, according to global health statistics (2020b), 4 out of 5 school-aged adolescents aged 11-17 years (81%) do not meet PA recommendations, with the proportion of girls (84.7%) not meeting this threshold being higher than that of boys (77.6%). This demonstrates that the trend of physical inactivity and, consequently, its associated diseases, continues to increase in adolescence, creating an alarming public health problem (Escalante, 2011).

According to the scientific literature, among girls, sedentary and unhealthy lifestyles are a trend that becomes significant from adolescence onwards (Troiano et al., 2008). A number of studies have also investigated factors affecting PA habits among adolescent girls and have highlighted various influences. Therefore, in order to understand their reduced participation in PA and sport, the factors that influence this situation should be analysed.

One of the biggest social influences is the media. Gómez-Colell (2015) argues that women’s sport is invisibilised by the media because it is considered less important. This is a further difficulty in encouraging adolescent girls to take up sport. There are a lack of female role models at this stage of life, which reinforces the message that sport is for men. Moreover, in many sports media, the few women who do appear in the coverage do so not because of their leading role as athletes, but as male companions. They are what Sáinz de Baranda (2010) refers to as “guests”: women who are not athletes but appear in sports coverage as partners, celebrities or amateurs accompanying the male protagonist (2010, p. 130). These women are featured in the media on account of their beauty or for being romantically involved with athletes, sending adolescent girls stereotypical messages and insights into their place in sport. For their part, Rodríguez and Miraflores (2018) account for the reduced participation of women in sport through the influence of myths that are preserved in the public perception and which defend, on the one hand, that PA masculinises women and, on the other, that girls are less interested in sport than boys. It is also important to note that the social sexism that has traditionally defined adolescent girls as weaker and less skilled in sport also permeates through the hidden curriculum of secondary school Physical Education (PE) classes, which further encourages the development of negative attitudes or indifference towards PA among adolescent girls (Granda-Vera et al., 2018). Finally, adolescent girls are additionally unable to find support in their immediate environment, especially in their families, so girls in this age group begin to prioritise types of activities other than sport. For all these reasons, the sporting sphere remains linked to masculinity not only in public perception, but also in practice. This leads adolescent girls to consider it to be a space that not only does not belong to them, but also one where they feel less valued, less competent and which presents fewer opportunities for participation and development (Flores-Fernández, 2020).

In light of these studies, it is clear that the factors influencing adolescent girls’ sustained participation in PA and sport are abundant and increasingly subtle and difficult to detect, making it more costly to design and implement interventions to improve the situation. For all of the above reasons, the aim of this systematic review (SR) is to identify the factors that influence adolescent girls to remain in or dropout of PA and sport.

Materials and methods

In order to guarantee the methodological rigour of this SR, the 27 items included in the updated PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement (Page et al., 2021) were applied.

Search strategy

In order to carry out the review, a search was conducted for scientific articles indexed in the Web of Science (WoS) database, which guarantees the impact index of the information sources and, therefore, their quality and scientific rigour. The search strategy aimed to identify articles that examined factors associated with PA and sport participation and dropout among adolescent girls. A search was carried out for articles in which a combination of the following keywords appeared in the abstract: (Physical activity OR Physical exercise OR Sport) AND (Adolesc* OR Children) AND (Female OR Gender OR Girl OR Wom*) AND (Barrier* OR Facilitator*).

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were: i) original, experimental articles addressing factors associated with adolescent girls’ participation or dropout from sport, ii) articles published between January 2010 and November 2022, iii) research with a sample of individuals up to 21 years of age, and iv) articles published in English, Spanish or Catalan. All research that: i) was not an original, experimental study; ii) was published prior to 2010, and iii) included participants outside the indicated age range, was excluded.

Procedure

In line with the PRISMA statement (Page et al., 2021), three stages (identification, screening and inclusion) were established in the article eligibility process. The identification phase resulted in a total of 597 items. In order to narrow the search and limit access to only sources of information of interest according to the purpose of the study, articles were filtered by areas of knowledge (Psichology, Behavioral Sciences, Educational Research, Sport Sciences, Social Issues, Women Studies). Following this, 11 studies were eliminated for being duplicates and 17 for being in a language other than English, Spanish or Catalan. The 3 review authors participated jointly in the screening phase, filtering by title and abstract, and 55 articles were selected. In order to comply with the participant age criteria, 3 participants were excluded. In the inclusion phase, relevant articles were selected through reading the full texts and determining their eligibility for the study. As a result, 29 articles were finally included. Subsequently, to extract the key information from the selected sample (n = 29), a content analysis was carried out by the three review authors in order to obtain the resulting data table (Table 1). Each of the authors entered information independently and the information was then cross-checked and contrasted in order to ensure that there was no bias in the information collected. Finally, after analysing the research, the essential variables on which to base the synthesis method were determined. Figure 1 shows a flow chart reflecting the process of searching for and selecting research for inclusion in this SR.

Results

Of the 29 articles reviewed, seven were qualitative research, two were mixed studies and the rest were quantitative research with very different designs.

Ten influential factors for the physical and sports participation of adolescent girls were identified and classified into internal or personal factors, with personal characteristics mainly related to self-determination and self-awareness, and external characteristics to environmental or contextual factors (Accardo et al., 2019). The internal factors appearing in the SR articles were: motivation (1), self-perception (2), self-presentation (3), sport identity (4) and changes associated with developmental stage (5); while the external factors were: sport environment (6), educational and PE environment (7), social support (8), role models (9) and gender stereotypes (10). Table 1 also lists each of the factors addressed in the articles included in this SR.

Discussion

The aim of this SR was to analyse the factors that influence participation in PA and sport among adolescent girls. A review of the 29 studies revealed multiple factors explaining girls’ sport involvement during this stage of life. Because of their large number, they are grouped into internal and external factors. In addition, for each factor or variable that conditions or hinders the participation of adolescent girls in PA and sport, proposals for improvement are provided that seek to reverse the trend of girls dropping out of sport during adolescence.

Internal factors

One main internal factor is motivation. Lack of motivation is a major barrier to sustained participation in PA and sport for adolescent girls. Some studies demonstrate that adolescence leads to a loss of motivation for PA (Knowles et al., 2014) and that boys are more motivated than girls. This situation is recurrent except when the motivation is linked to aesthetics (Frömel et al., 2022), where girls score higher, perhaps due to the social pressure that adolescent girls face in relation to their physical appearance. In this regard, Budd et al. (2018) demonstrate how intrinsic motivation, independent of external stimuli and related to one’s own enjoyment of the activity, is an important predictor of participation in PA (Frömel et al., 2022). However, girls are more extrinsically motivated, for example, by social and health-related issues (Kopcakova et al., 2015). Therefore, to prevent girls from dropping out, motivational differences between the sexes should be considered and interventions should be implemented that take into account the factors that motivate girls and boys, in order to provide them with PA experiences linked to their interests (Zucchetti et al., 2013). In addition, it is vital to conduct further research into why girls do not perceive the practice of PA as an end in itself.

A second internal factor is self-perception in sports practice. Self-perception is a person’s appreciation of him/herself and it is formed through experiences with the environment (Shavelson et al., 1976). Negative self-perception and lack of confidence in one’s own abilities are barriers to adolescent girls’ participation. Cowley et al. (2021) explain that girls feel a greater lack of confidence and also embarrassment doing PA in public. Conversely, a sense of competence and a higher physical self-concept have been shown to increase the likelihood of maintaining and acquiring active habits (Zook et al., 2014). In order to avoid dropout, it is therefore necessary to promote a sporting context that focuses on developing positive self-perception in adolescent girls, where they obtain positive results that improve their self-perception, and to design activities that are centred around them (Beasley and Garn, 2013).

Another factor to consider is self-presentation, the process by which people try to influence and control others’ impressions of them. Knowles et al. (2014) report that girls are more concerned about self-presentation when doing PA with boys. When they compare themselves with their male peers, they feel that they are not as skilled as them (Bevan and Fane, 2017) and experience discomfort, insecurity and worry (Knowles et al., 2014; Cowley et al., 2021; O’Reilly et al., 2022), which can be an added difficulty for them, especially in co-educational PE classes. Recent studies focusing on adolescent girls have found that girls often prefer to take PE lessons separately from boys (Cowley et al., 2021), so this should be seriously considered. It is not a question of reverting to the segregation of students by gender, but of considering the establishment of certain tasks or sessions in different groups working on the same content, so that all students have the possibility of participating with peers who do not have a physical starting advantage, creating situations that offer them positive experiences in relation to the possibility of success.

On the other hand, sport identity, defined as the degree of strength and exclusivity with which a person identifies with the role of athlete, is another factor influencing sustained participation in PA and sport. In their study, Eime et al. (2016) explain how for boys it is relatively easy for their sport identity and their masculine identity to align, while for girls this relationship is not straightforward. This mismatch between female stereotypes and the traditional sport model is a further obstacle to their participation and adherence (Bevan et al., 2021). Adolescent girls must negotiate between gender norms and their enjoyment of sport. Therefore, future studies should address this issue and work towards the eradication of gender stereotypes, as well as promote a sporting model different to the hegemonic one, in which girls find their place and with which they can identify.

Finally, another internal factor detected in several of the articles is the physical, emotional and social changes that accompany adolescence (Davison et al., 2010). During puberty and adolescence, significant bodily changes occur. In the case of girls, these include the widening of the pelvis, accumulation of fat in the legs and hips, breast enlargement and the onset of menstruation. In this regard, Zook et al. (2014) demonstrated how early pubertal development and menstruation can decrease PA practice. Pubertal physical changes pose an added difficulty for girls, as they have to expose themselves in public spaces where they believe that their bodies are looked at, commented upon and evaluated (Fredrickson and Roberts, 1997). In addition to bodily changes, this period brings new commitments linked to leisure, work and study, which also lead to a change in priorities. Thus, during adolescence a distancing from sport activities takes place (Eime et al., 2015, 2016), and girls are more prone to this (Dawes et al., 2014). This shift in priorities, understood as an internal factor, can be explained by taking into account external factors, such as gender expectations and social norms. In line with Ana de Miguel, at the adolescent age, cultural gender norms, with their different associations for boys and girls, are very effective. Among the contradictory messages that girls receive socially in adolescence, those related to the practice of PA are not a priority or relevant. On the other hand, they are bombarded with notions of pleasantness and beauty and, in recent years, particularly with hypersexualisation (De Miguel, 2016, p. 65). Advertising recreates images of stereotypical women committed to always looking beautiful, made-up and well-groomed, which is incompatible with sport. These representations hinder their potential, whilst boys are encouraged to develop their personality and identity (Valcárcel, 2008, pp. 192-198). It is vital that schools work on these aspects in PE classes. Teaching adolescents to be critical is fundamental in order to free them from the gender norms that constrain and limit them, particularly in the case of girls.

External factors

Among the external factors influencing participation in PA and sport, society is a determining factor. Generally, girls’ contribution to sport is often underestimated in all respects, leaving them feeling less valued (Cowley et al., 2021). Sport is a phenomenon that was designed by and for men, so women have had to adapt to a model which, in many cases, they do not feel aligned with and in the design of which they did not participate, nor were they taken into account. In this sense, girls feel “invited” to participate in a field that does not belong to them, and which represents a handicap when it comes to establishing stable and deep ties with the activity.

Along these lines, Eime et al. (2015) argue that adolescent girls should be fully involved in decisions about their sporting lives and should do so in an environment where they feel respected, empowered and have a voice, key strategy for keeping them physically active. This environment should provide alternatives to traditional and competitive sports, and incorporate other activities that enhance social aspects, as well as be a space in which the level of skill is not set by males (Davison et al., 2010; Owen et al., 2019).

Despite advances in feminism, gender stereotypes continue to be a factor that negatively influence adolescent girls’ PA (O’Reilly et al., 2022). Social and cultural pressures instil in girls perceptions of activities “more appropriate to their sex” (Gil-Madrona et al., 2017), inhibiting them from participating in sports traditionally considered masculine. Bevan and Fane (2017) explain that girls turn away from the sporting pathway because they feel the need to conform to gender norms and social expectations, as they observe that those who oppose these norms are marginalised and linked to masculinity, aspects that have a deterrent effect on their participation (Bevan et al., 2021). It is therefore absolutely necessary to include gender and feminist education in the training programmes of all sport professions. Only in this way will adolescent girls find it easier to maintain their sporting careers and reduce the dropout rate from PA.

Another external factor identified is the lack of role models, which also leads girls to accept sport as a male domain (Bevan et al., 2021). Research by Cowley et al. (2021) looks at how differences between female and male athletes in all aspects mean that girls see no chance of progressing in sport. In addition, Bevan et al. (2021) highlight the need for the media to be used to promote role models, as having role models at a high level is one way for adolescent girls to realise that they have the possibility to grow within the world of sport (Drummond et al., 2022). Therefore, teachers in schools should be committed to counteracting the negative influence of the media by providing socially male and female role models in equal quantity and frequency, and eliminating stereotypes so that girls also have their own role models and see examples of successful women in the field of sport.

In this regard, the school is an ideal environment for the promotion of PA, as the structured nature of the school day provides numerous opportunities for its practice (PE, active transport, extracurricular sport…) (Owen et al., 2019). Specifically, Beasley and Garn (2013) consider that PE is the subject that most influences sustained participation in PA, although its presence in the school curriculum does not guarantee a lifestyle (Castro-Sánchez et al., 2016). This subject has historically been considered a male space dominated by boys for physiological reasons (Gil-Madrona et al., 2014). Given the predominance of traditionally male-dominated activities and their androcentric approach (Ahmed et al., 2020), PE may be another contributor to adolescent girls’ lack of interest. In PE classes, girls experience a lack of encouragement from teachers, greater bias and favouritism towards their male peers (Owen et al., 2019), the use of sexist language (Bevan and Fane, 2017) and an emphasis on sports that are considered masculine (O’Reilly et al., 2022). Therefore, in order to increase girls’ interest in PA inside and outside the classroom, recent studies have demonstrated the importance of the PE teacher (Flores-Rodriguez and Alvite-de-Pablo, 2023). The educational institution and teaching staff play an important role in the eradication of gender stereotypes in PA and sport (O’Reilly et al., 2022). It is therefore up to them to help put an end to stereotypical beliefs and sexist behaviour in sport by motivating adolescent girls further and, above all, more effectively. However, without the necessary training, this progress is impossible and several studies have analysed the scarce or non-existent feminist teacher training in the curricula of Physical Activity and Sport Science degrees (Serra et al., 2018). This is an aspect that should be taken into account by teacher training centres, where the feminist perspective and the study of women should be cross-cutting content in all subjects, as adolescent girls make up half of the student body.

In addition, adolescent girls do not report high levels of support for PA from their families, friends and teachers (Eime et al., 2016). According to MacPherson et al. (2016), social interactions that take place in the sports environment have a decisive impact on the sustained participation of adolescent girls, so it is essential to promote the development of groups of girls who have positive psychosocial experiences in sport in order to facilitate their adherence. Social connection with peers is vital and maintains adolescent girls’ interest (Bevan et al., 2021). However, in the early stages, the family is a key agent in helping girls to develop sport habits that will last during later stages (Castro-Sánchez et al., 2016). In this sense, adolescents with active parents are more likely to engage in regular PA (Mateo-Orcajada et al., 2021). In addition, Diaconu-Gherasim and Duca (2018) demonstrate that support from mothers and fathers increases the interest and motivation of adolescent girls.

Conclusions

This SR summarises the evidence collected on the factors that influence the sustained participation or dropout from PA and sport among adolescent girls. Internal factors include motivation, self-perception, self-presentation, sport identity and integral changes associated with adolescence and puberty. External factors include the sport environment, the educational context and PE teachers, social support, role models, and gender stereotypes and roles in sport. Taking into account the influence that these factors have on the physical and sports participation of adolescent girls, a multifactorial response that addresses these psychological, social and environmental components in a holistic way is necessary, in order to create sports policies focused on maintaining adolescent girls’ sustained participation in PA and for sport to be effective.

Limitations

This study does have some limitations. One of these is publication bias. The available research may not be a thorough representation of existing research, given that a single database has been used and studies that do not obtain optimal or significant results are not included. On the other hand, in studies with participants of both sexes, some factors mentioned in the review may not only affect girls. This may pose difficulties in targeting future interventions that take into account the sex/gender system. Finally, another limitation is the great heterogeneity of PA populations, methodologies and contexts reflected in the papers included in the review, which may affect the results of the study.

Funding

This work has been funded by the Conselleria de Cultura i Esport de la Generalitat Valenciana through the Women and Sport Chair of the University of Valencia. Professor Ruth Cabeza-Ruiz is also a beneficiary of an Aid for the Recalibration of the Spanish University System for 2021-2023 from the Ministry of Universities, Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan, funded by the European Union-NextGenerationEU.

References

[1] Accardo, A. L., Bean, K., Cook, B., Gillies, A., Edgington, R., Kuder, S. J., & Bomgardner, E. M. (2019). College access, success and equity for students on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(12), 4877-4890. doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04205-8

[2] Ahmed, D., Ho, W. K. Y., Al-Haramlah, A., & Mataruna-Dos-Santos, L. J. (2020). Motivation to participate in physical activity and sports: Age transition and gender differences among India’s adolescents. Cogent Psychology, 7(1), 1798633. doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2020.1798633

[3] Amado, D., Sánchez-Oliva, D., González-Ponce, I., Pulido-González, J. J., & Sánchez-Miguel, P. A. (2015). Incidence of Parental Support and Pressure on Their Children’s Motivational Processes towards Sport Practice Regarding Gender. PLOS ONE, 10(6), e0128015. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128015

[4] Beasley, E. K., & Garn, A. C. (2013). An Investigation of Adolescent Girls’ Global Self-Concept, Physical Self-Concept, Identified Regulation, and Leisure-Time Physical Activity in Physical Education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 32(3), 237-252. doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.32.3.237

[5] Bevan, N., Drummond, C., Abery, L., Elliott, S., Pennesi, J.L., Prichard, I., Lewis, L. K., & Drummond, M. (2021). More opportunities, same challenges: Adolescent girls in sports that are traditionally constructed as masculine. Sport, Education and Society, 26(6), 592-605. doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1768525

[6] Bevan, N., & Fane, J. (2017). Embedding a critical inquiry approach across the AC:HPE to support adolescent girls in participating in traditionally masculinised sport. International Journal of Learning in Social Contexts, 21, 138-151. doi.org/10.18793/lcj2017.21.11

[7] Budd, E. L., McQueen, A., Eyler, A. A., Haire-Joshu, D., Auslander, W. F., & Brownson, R. C. (2018). The role of physical activity enjoyment in the pathways from the social and physical environments to physical activity of early adolescent girls. Preventive Medicine, 111, 6-13. doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.02.015

[8] Castro-Sánchez, M., Zurita-Ortega, F., Martínez-Martínez, A., Chacón-Cuberos, R., & Espejo-Garcés, T. (2016). Clima motivacional de los adolescentes y su relación con el género, la práctica de actividad física, la modalidad deportiva, la práctica deportiva federada y la actividad física familiar (.Motivational climate of adolescents and their relationship to gender, physical activity, sport, federated sport and physical activity family) RICYDE. Revista Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte, 12(45), 262-277. doi.org/10.5232/ricyde2016.04504

[9] Chacón-Cuberos, R., Zurita-Ortega, F., Ramírez-Granizo, I., & Castro-Sánchez, M. (2020). Physical Activity and Academic Performance in Children and Preadolescents: A Systematic Review. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 139, 1-9. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2020/1).139.01

[10] Cowley, E. S., Watson, P. M., Foweather, L., Belton, S., Thompson, A., Thijssen, D., & Wagenmakers, A. J. M. (2021). “Girls Aren’t Meant to Exercise”: Perceived Influences on Physical Activity among Adolescent Girls—The HERizon Project. Children, 8(1), 31. doi.org/10.3390/children8010031

[11] Davison, K. K., Schmalz, D. L., & Downs, D. S. (2010). Hop, Skip … No! Explaining Adolescent Girls’ Disinclination for Physical Activity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 39(3), 290-302. doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9180-x

[12] Dawes, N. P., Vest, A., & Simpkins, S. (2014). Youth Participation in Organized and Informal Sports Activities Across Childhood and Adolescence: Exploring the Relationships of Motivational Beliefs, Developmental Stage and Gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(8), 1374-1388. doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9980-y

[13] De Miguel, A. (2016). Neoliberalismo sexual. El mito de la libre elección. Cátedra.

[14] Diaconu-Gherasim, L. R., & Duca, D. S. (2018). Parent–Adolescent Attachment and Interpersonal Relationships in Sports Teams: Exploring the Gender Differences. Gender Issues, 35(1), 21-37. doi.org/10.1007/s12147-017-9190-0

[15] Drummond, M., Drummond, C., Elliott, S., Prichard, I., Pennesi, J.L., Lewis, L. K., Bailey, C., & Bevan, N. (2022). Girls and Young Women in Community Sport: A South Australian Perspective. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3, 803487. doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2021.803487

[16] Eime, R. M., Casey, M. M., Harvey, J. T., Sawyer, N. A., Symons, C. M., & Payne, W. R. (2015). Socioecological factors potentially associated with participation in physical activity and sport: A longitudinal study of adolescent girls. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18(6), 684-690. doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2014.09.012

[17] Eime, R. M., Harvey, J. T., Sawyer, N. A., Craike, M. J., Symons, C. M., & Payne, W. R. (2016). Changes in sport and physical activity participation for adolescent females: A longitudinal study. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 533. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3203-x

[18] Escalante, Y. (2011). Actividad física, ejercicio físico y condición física en el ámbito de la salud pública. Revista española de salud pública, 85(4), 325-328. doi.org/10.1590/S1135-57272011000400001

[19] Flores-Fernández, Z. (2020). Mujer y deporte en México. Hacia una igualdad sustancial. Retos: nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación, 37, 222-226. dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7243272

[20] Flores-Rodríguez, J., & Alvite-de-Pablo, J. R. (2023). Prosocial Behaviours, Physical Activity and Personal and Social Responsibility Profile in Children and Adolescents. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 153, 70-81. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2023/3).153.07

[21] Fredrickson, B.L., & Roberts, T.A. (1997). Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173-206. doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

[22] Frömel, K., Groffik, D., Šafář, M., & Mitáš, J. (2022). Differences and Associations between Physical Activity Motives and Types of Physical Activity among Adolescent Boys and Girls. BioMed Research International, 1-13. doi.org/10.1155/2022/6305204

[23] Gil-Madrona, P., Cachón-Zagalaz, J., Diaz-Suarez, A., Valdivia-Moral, P., & Zagalaz-Sánchez, M. L. (2014). As meninas também querem brincar: a participaçâo conjunta de meninos e meninas em atividades físicas näo organizadas no contexto escolar. Movimento (ESEFID/UFRGS), 20(1), 103. doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.38070

[24] Gil-Madrona, P., Valdivia-Moral, P., González-Víllora, S., & Zagalaz, M. L. (2017). Percepciones y comportamientos de discriminación sexual en la práctica de ejercicio físico entre los hombres y mujeres preadolescentes en el tiempo de ocio (Perceptions and behaviors of sex discrimination in the practice of physical exercise among men and women in pre-adolescents leisure time). Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 26(2), 81-86. dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6140377

[25] Gómez-Colell, E. (2015). Adolescencia y deporte: Adolescence and Sport: Lack of Female Athletes as Role Models in the Spanish Media. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 122, 81-87. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2015/4).122.09

[26] Granda-Vera, J., Alemany-Arrebola, I., & Aguilar-García, N. (2018). Gender and its Relationship with the Practice of Physical Activity and Sporty. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 136, 21-33. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2018/2).132.09

[27] Kirby, J., Levin, K.A., & Inchley, J. (2012). Associations between the school environment and adolescent girls’ physical activity. Health Education Research, 27(1), 101-114. doi.org/10.1093/her/cyr090

[28] Knowles, A.-M., Niven, A., & Fawkner, S. (2014). ‘Once upon a time I used to be active’. Adopting a narrative approach to understanding physical activity behaviour in adolescent girls. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 6(1), 62-76. doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2013.766816

[29] Kopcakova, J., Veselska, Z., Geckova, A., Kalman, M., van Dijk, J., & Reijneveld, S. (2015). Do Motives to Undertake Physical Activity Relate to Physical Activity in Adolescent Boys and Girls? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(7), 7656-7666. doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120707656

[30] Lawler, M., Heary, C., Shorter, G., & Nixon, E. (2022). Peer and parental processes predict distinct patterns of physical activity participation among adolescent girls and boys. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 20(2), 497-514. doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2021.1891118

[31] MacPherson, E., Kerr, G., & Stirling, A. (2016). The influence of peer groups in organized sport on female adolescents’ identity development. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 23, 73-81. doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.10.002

[32] Mateo-Orcajada, A., Vaquero-Cristóbal, R., Abenza-Cano, L., Martínez-Castro, S. M., Gallardo-Guerrero, A. M., Leiva-Arcas, A., & Sánchez-Pato, A. (2021). Influência do gênero, nível educacional e prática desportiva dos pais nos hábitos esportivos das crianças em idade escolar. Movimento, e27057. doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.109610

[33] Mitchell, F., Gray, S., & Inchley, J. (2015). ‘This choice thing really works … ’ Changes in experiences and engagement of adolescent girls in physical education classes, during a school-based physical activity programme. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 20(6), 593-611. doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2013.837433

[34] Morano, M., Robazza, C., Ruiz, M. C., Cataldi, S., Fischetti, F., & Bortoli, L. (2020). Gender-Typed Sport Practice, Physical Self-Perceptions, and Performance-Related Emotions in Adolescent Girls. Sustainability, 12(20), 8518. doi.org/10.3390/su12208518

[35] O’Reilly, M., Talbot, A., & Harrington, D. (2022). Adolescent perspectives on gendered ideologies in physical activity within schools: Reflections on a female-focused intervention. Feminism & Psychology, 095935352211090. doi.org/10.1177/09593535221109040

[36] Organización Mundial de la Salud. (2020a). Directrices de la OMS sobre actividad física y hábitos sedentarios: De un vistazo. Organización Mundial de la Salud. apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/337004

[37] Organización Mundial de la Salud. (2020b). Estadísticas sanitarias mundiales 2020: Monitoreando la salud para los ODS, objetivo de desarrollo sostenible. Organización Mundial de la Salud. apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/338072

[38] Owen, M., Kerner, C., Newson, L., Noonan, R., Curry, W., Kosteli, M., & Fairclough, S. (2019). Investigating Adolescent Girls’ Perceptions and Experiences of School‐Based Physical Activity to Inform the Girls’ Peer Activity Intervention Study. Journal of School Health, 89(9), 730-738. doi.org/10.1111/josh.12812

[39] Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., Stewart, L. A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting, P. & Moher, D. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas (The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews). Revista Española de Cardiología, 74(9), 790-799. doi.org/10.1016/j.recesp.2021.06.016

[40] Rodríguez-Rodríguez, L. & Miraflores-Gómez, E. (2018). Propuesta de igualdad de género en Educación Física: adaptaciones de las normas en fútbol. Retos, 33, 293-297. dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6367776

[41] Sáinz de Baranda Andújar, C. (2010). Mujeres y deporte en los medios de comunicación. Estudio de la prensa deportiva española (1979- 2010) [Tesis doctoral]. Universidad Carlos III de Madrid.

[42] Serra, P., Soler, S., Prat, M., Vizcarra, M.T., Garay, B., & Flintoff, A. (2018). The (in)visibility of gender knowledge in the Physical Activity and Sport Science degree in Spain. Sport, Education and Society, 23(4), 324-338, doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1199016

[43] Shavelson, R. J., Hubner, J. J., & Stanton, G. C. (1976). Self-Concept: Validation of Construct Interpretations. Review of Educational Research, 46(3), 407-441. doi.org/10.3102/00346543046003407

[44] Troiano, R. P., Berrigan, D., Dodd, K. W., Mâsse, L. C., Tilert, T., & McDowell, M. (2008). Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 40(1), 181-188. doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3

[45] Valcárcel, A. (2008). Feminismo en el mundo global. Cátedra.

[46] Zook, K. R., Saksvig, B. I., Wu, T. T., & Young, D. R. (2014). Physical Activity Trajectories and Multilevel Factors Among Adolescent Girls. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(1), 74-80. doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.015

[47] Zucchetti, G., Candela, F., Rabaglietti, E., & Marzari, A. (2013). Italian Early Adolescent Females’ Intrinsic Motivation in Sport: An Explorative Study of Psychological and Sociorelational Correlates. Physical Culture and Sport. Studies and Research, 59(1), 11-20. doi.org/10.2478/pcssr-2013-0022

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: November 13, 2023

Accepted: March 7, 2024

Published: July 1, 2024

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en