Experiences of Olympic Hopefuls of the Disruption of the Olympic Cycle at Tokyo 2020

*Corresponding author: Rocío Zamora rocio.zamora@uab.cat

Cite this article

Zamora-Solé, R., Alcaraz, S., Regüela, S., & Torregrossa, M. (2022). Experiences of Olympic Hopefuls of the Disruption of the Olympic Cycle at Tokyo 2020. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 148, 1-9.

https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2022/2).148.01

Abstract

Lockdown due to COVID-19 and the postponement of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games meant Olympic hopefuls experienced an uncertain and changing Olympic cycle. This paper describes the experiences of high-level and high-performance athletes amidst the disruption of the Olympic cycle caused by the concurrent non-normative transitions of coronavirus lockdown and the postponement of the Olympic Games. Twenty-five athletes (14 females and 11 males; age M = 26.2, SD = 6.99) were interviewed via videoconference during the eighth week of confinement. An inductive reflexive thematic analysis was carried out to organise the results into four thematic axes: (a) pre-confinement, (b) confinement, (c) post-confinement and (d) Tokyo 2020 + 1. The announcement of the postponement of the Olympic Games was recognised as a milestone that changed the lockdown experience, transforming the perception of lockdown as a threat into an opportunity. While the transitions were experienced in a variety of ways, the presence of sport identity psychological resources (i.e., frustration tolerance and resilience), the development of extra-sport identities (i.e., dual careers) and sport lifestyle (e.g., experiences at meets) are highlighted as facilitating factors in coping with and managing these concurrent transitions. The results obtained can help sports psychology professionals and others in the field to aid athletes in coping with the disruption of the Olympic cycle, as well as in coping with other unexpected situations.

Introduction

The 32nd Olympic Games were scheduled to be held in July 2020 in Tokyo. To this end, athletes from all over the world were preparing to face the final phase on the road to Olympic qualification. Towards the end of 2019, the first cases of infection from a new coronavirus strain causing COVID-19, were announced and, due to the evolution of the situation, a global pandemic was declared by the World Health Organisation (WHO) on 11 March 2020. COVID-19 disrupted the daily lives of a large part of the world’s population and in doing so, also caused major disruption to the Olympic cycle. Like the rest of the population, athletes faced lockdown enforced by the authorities of their countries and, in their specific case, they also had to deal with the postponement of the Olympic Games, a sporting goal for which they had been preparing for at least four years. In this paper the experiences of high performance athletes (DAR) and high level athletes (DAN) will be explored, as they underwent these two transitions concurrently (i.e., lockdown and postponement of the Olympic Games).

To this end, the paper will adopt the position of the International Society of Sport Psychology (ISSP) on the career development and transitions of athletes (Stambulova et al., 2020a). In it, transitions are defined as phases of change and are highlighted as one of the main conceptualisations in the discourse on sport careers. Career transitions have been classified into three categories, according to their predictability: (a) normative, those that are relatively predictable and derived from the logic of athlete development; (b) non-normative, those that are difficult to predict; and (c) quasi-normative, those that are predictable for a particular group of athletes. The former includes the transition from junior to senior (Torregrossa et al., 2016) and retirement from elite sport (Torregrossa et al., 2015; Jordana et al., 2017), the latter include aspects such as sport injuries (Palmi & Solé-Cases, 2014), in addition to sport migration (Prato et al., 2020). Lockdown due to COVID-19 and the postponement of the Olympic Games can be conceptualised as non-normative transitions; the former is an event while the latter is not (see Schlossberg, 1981). Stambulova (2003) points out that non-normative transitions are more likely to turn into crises (see also Stambulova et al., 2020a), due to the inherent difficulty of anticipating them.

Focusing on the experience of lockdown due to COVID-19, Odriozola-González et al. (2020) conducted a quantitative study to analyse the short-term psychological effects of the COVID-19 crisis and lockdown on the Spanish population. Specifically, the study sought to assess symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress, which were measured through a questionnaire. The results showed that, out of a total of 3550 participants, 32.4% showed symptoms of anxiety, 44.1% of depression and 37.0% of stress. Pons et al. (2020) sought to describe and characterise the overall impact that lockdown had on young athletes. The results of this quantitative study showed that the assessment of lockdown was negative in terms of impact on both mental health and different spheres of life (e.g. dual career). Clemente-Suárez et al. (2020) conducted a study of 175 Olympians and Paralympians with the understanding that this population faced an additional barrier: the postponement of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. The study aimed to analyse the effect of psychological profile, academic level and gender on the perception of personal and professional threat in the run-up to the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. It demonstrated that both Olympians and Paralympians had a negative perception of lockdown in relation to their training routines, but not in their performance in the run-up to the Games. At the same time, quarantine did not have a significant impact on athletes’ anxiety responses, which they attributed to the experience and coping strategies that athletes develop.

The Olympic Games constitute the pinnacle event for many sports and it is common for athletes and sports organisations alike to plan their activities around the Olympic cycle (Wylleman et al., 2012; Solanellas and Camps, 2017; Henriksen et al., 2020a). The disruption of the Olympic cycle resulted in the postponement of the Olympic Games for a year and complete suspension was threatened up until a few days before it was due to take place. This alteration occurred in the last phase of preparation for Olympic qualification, causing career disruption potentially resulting in a loss of motivation, identity and meaning (Henriksen et al., 2020b). Oblinger-Peters & Krenn (2020) conducted a qualitative study with the aim of exploring subjective perceptions of Austrian athletes and coaches surrounding the postponement of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. It was discovered that postponement was experienced in various ways and that the immediate emotional responses ranged from confusion, disappointment and relief. The main consequences associated with postponement included: prolonged physical and psychological strain, concern about performance impact, loss of motivation, as well as opportunity for recovery and improvement.

In analysing the impact of the concurrent non-normative transitions of lockdown due to COVID-19 and the postponement of the Olympic Games, Stambulova et al., (2020b) differentiate between three possible scenarios depending on the stage of the athlete’s sporting career. The first scenario is rejection of the situation and it is considered typical of athletes who are towards the end of their careers and who have already participated in an Olympic Games and even won medals. They therefore do not want to face the uncertainty that comes with the disruption of the Olympic cycle and decide that it is an opportune time to retire. The second scenario is acceptance of the situation, representing early/mid-career athletes who are less affected by the disruption of the Olympic cycle, whether the intermediate postponement or even the complete suspension, because they still have the possibility of preparing for later cycles (e.g. the 2024 Olympic Games). This group of athletes would prefer to take a break and prepare strategically for the next Olympic Games as they do not consider that they have the resources to cope with the demands imposed by COVID-19 and the postponement of the Games. The final scenario constitutes one of struggle and represents athletes who are in the middle or towards the end of their careers, who have accumulated numerous resources and experiences, and decide to face COVID-19 with an active struggle to adapt and become stronger in this transition.

Taku & Arai (2020) point out that COVID-19 sets a precedent with regard to the certainty of holding sporting events, such as the Olympic Games. Investigating into the history of the Olympic Games, Constandt & Willem (2021) recall that in 1920 the Olympic Games took place in Antwerp. These Games took place in the aftermath of the First World War and the Spanish flu pandemic. Little is known about the experiences of the athletes, but like the current pandemic, the Games took place during a public health crisis. Symbolically, these Games represented the rebirth of the Olympic movement.

As has been observed, the studies that have been carried out to date have focusedmainly on exploring COVID-19 lockdown and the postponement of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games in a quantitative manner. In contrast, few studies have used qualitative methodology to explore experiences related to the disruption of the Olympic cycle, resulting from lockdown and postponement. In order to provide insight into the experiences of aspiring male and female Olympians who underwent these concurrent non-normative transitions, this study presents an account through a retrospective exploration (of lockdown) and a prospective one (in relation to the eventual hosting of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games in 2021).

Methodology

In this paper, qualitative research from a constructivist philosophical position was conducted. In other words, the research sought to understand the meanings that people attribute to lived experiences. To this end, two assumptions were made: (a) there is no external reality independent of people, but reality is shaped in relation to experiences and (b) knowledge is jointly constructed through interactions between participant and researcher (see Poucher et al., 2020).

Participants

A convenience sampling was carried out and 25 DAN and DAR athletes linked to a High Performance Sports Centre participated on a voluntary basis: 14 women and 11 men (M = 26.2 SD = 6.9). 88% participated in individual sports and 12% in team sports. 84% were pursuing a dual career, i.e. combining sport and studies or work (Stambulova & Wylleman, 2015). The selection criteria was to either have qualified or be in the process of qualifying for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games (qualifiers: 4 and in the process of qualifying: 21).

Instrument

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in order to enable a detailed account of the participants’ experiences. The interviews were conducted by the authors RZS and SR and the authors MT and SA. An interview script (see supplementary material) was prepared for the exploration of the following thematic axes: (a) sporting career, (b) importance of the Olympic Games, (c) lockdown experience, (d) vision of the post-lockdown world and (e) deferred pathway to Tokyo 2020. During the interview, participants were invited to share their stories about lockdown and the postponement of the Olympic Games.

Procedure

After obtaining approval from the University Ethics Committee (CEEAH 5180), participants were selected and convened. Once participation was agreed, the project information sheet and the informed consent form were sent out. All participants signed the informed consent form before participating in the study. Each participant took part in a semi-structured synchronous interview conducted via videoconference, lasting between 30 and 90 minutes. Interviews were conducted in May 2020, following eight weeks of lockdown, as permission for outdoor physical activity began to be authorised. The time slots allocated for sporting activities were longer for DAN athletes and they also had the right to travel outside the municipality. All interviews were audio and video recorded and then transcribed following Jefferson’s methodology (Bassi-Follari, 2015). Due to the possibility of identifying the participants, pseudonyms were used to preserve confidentiality.

Data analysis

Based on reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2019), an inductive analysis was carried out adhering to the following phases: (a) data familiarisation, (b) code generation, (c) initial theme creation, (d) theme and code revision, (e) final definition of themes and (f) report writing. To ensure scientific rigour, critical peer reviews were conducted in order to raise observations on the process of topic generation and representation (Smith & McGannon, 2018).

Results and Discussion

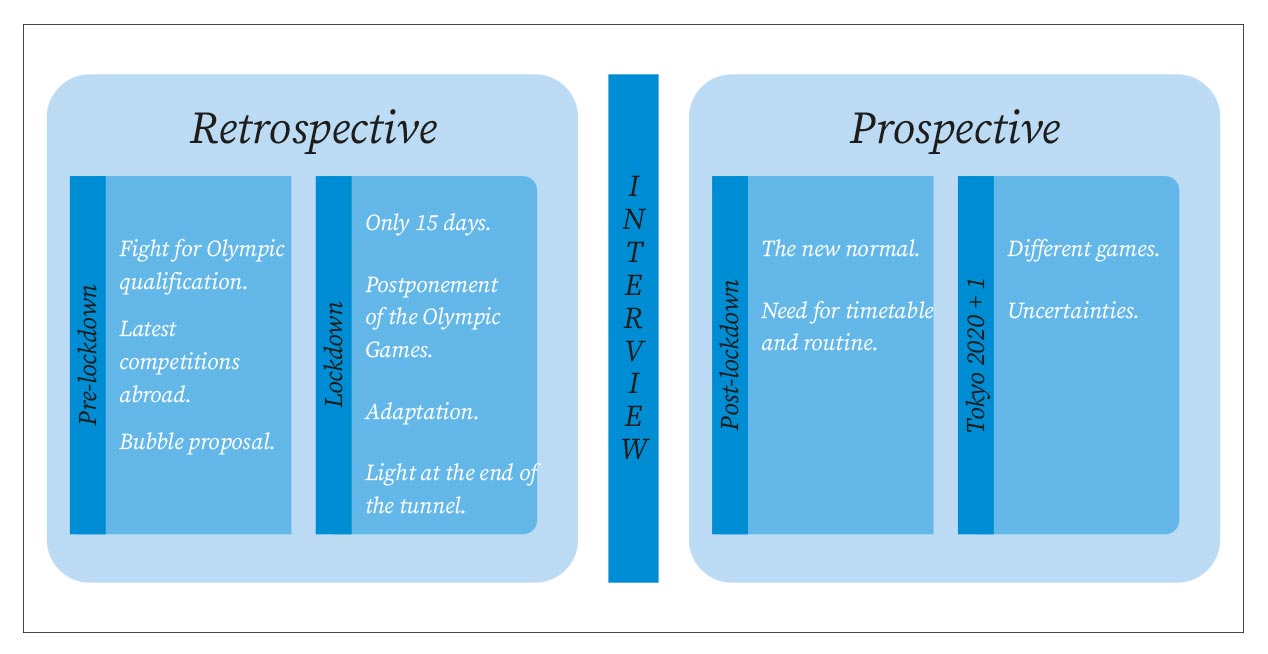

Considering that the description and interpretation of meanings are closely related, the Results and Discussion sections are combined in an attempt to interweave the experiences of the athletes with the scientific literature. Figure 1 summarises the themes and sub-themes resulting from the inductive reflective thematic analysis. These are structured along a timeline, with the first two themes reflecting the retrospective view at the time of the interview (regarding lockdown) and the last two reflecting the prospective view (of postponement).

Retrospective analysis

The following is a retrospective account of athletes’ experiences of pre-lockdown and lockdown phases.

Pre-lockdown

Competing for Olympic qualification

The first four months of 2020 saw major competitions for most athletes who were still competing to qualify for the Olympics. Depending on the sporting discipline, qualification depended on the result of participation in a pre-Olympic competitions (e.g. water sports) or on the sum of points obtained in multiple competitions and overall ranking (e.g. athletics). In both cases, and as noted by Henriksen et al. (2020a), the pre-lockdown stage was a phase of intense training in order to achieve peak fitness. Clara explains: “[…] I remember the last days of training, we did so much, so much, so much, that we would get there and we couldn’t even study.”

Final competitions abroad

Days before the establishment of the state of alarm in Spain, some athletes sought to compete in their final competitions abroad. The global situation regarding COVID-19 was becoming more complicated day by day, and travelling abroad implied a fear of not being able to return home and of being stigmatised on the basis of being a Spanish athlete (due to the fact that Spain was gradually becoming one of the countries most affected by the number of contagions). Brooks et al. (2020) highlighted stigmatisation as one of the main post-lockdown stressors; i.e. rejection, fear, and cessation of invitations to social events for fear of contagion. The results of the present study showed that stigmatisation was a stressor present, even prior to lockdown.

“[…] Before lockdown started, we were travelling to (a country) that had a European Cup which was a qualifier, it was one of the most important competitions of the season. And when we arrived, we had to go home the next day without competing because [country] had declared that Spaniards were not allowed in [country]. To be honest, that was a bit of a difficult time, realising: “Damn! Competitions are being postponed and I’m not sure when I will compete, where I will compete or how I will qualify’. It was quite a difficult few days.”

Bubble proposal

In the days leading up to the imposition of lockdown, there was a sense of tension in the high performance centre. Faced with the exponential growth of cases in Spain, management opted to anticipate the circumstances and offer an alternative plan so that athletes with the possibility of Olympic participation could continue training in a safe space. They gathered all the athletes and coaches together and offered them the possibility of lockdown in the centre in order to continue training. This lockdown meant that for the duration of the state of alarm (initially only 15 days) they could not leave the centre and, in turn, no one could enter. In response to this communication, two positions emerged: those who decided to lockdown in the centre and those who preferred to do so at home with their loved ones. Following the communication, those who had decided to lockdown in the centre returned home to pack their bags, and it was then that the situation changed. With the confirmation of a positive test result at the centre, the possibility of lockdown there became impossible, and the institution had to be closed. Laia comments: “If I had been staying there and had my room and my space, I don’t know (.) I might have reacted differently. But I just said ‘no‘. And I felt really guilty, because in the end I was deciding not to train.”

Lockdown

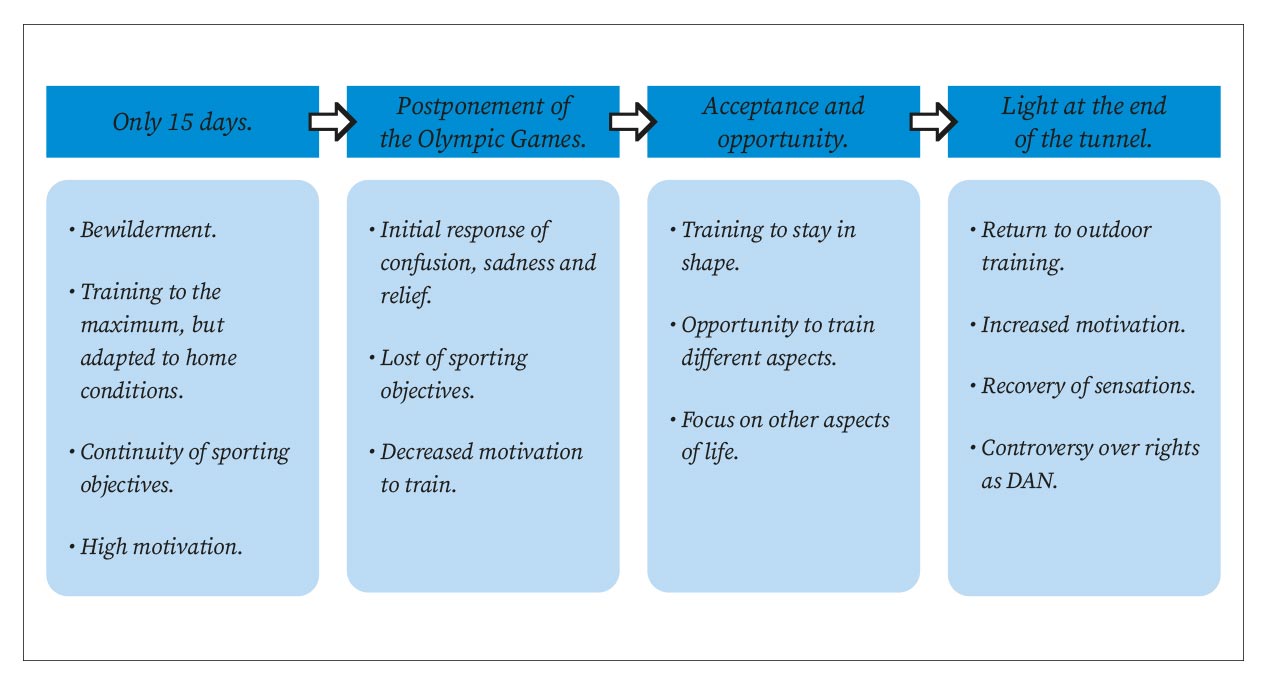

Most athletes identified four phases within lockdown. Within them it can be observed how the two transitions have been interconnected. The first phase, coded as “Only 15 days”,captures the initial belief regarding the duration of lockdown. Putting aside the bewilderment and uncertainty of a new and unforeseen situation, given that the Olympic objective was still viable, training sessions were made just as demanding as before this new reality. Motivation remained high. Jordi commented: “Well, this is only going to last a week, two at the most, and then things will go back to normal. I even trained harder than (…) I train normally, I did some pretty heavy sessions on the treadmill.”

The second phase coded as “Postponement of The Olympic Games” followed the announcement of the postponement of the Olympic Games. In the days leading up to the Olympics, the sporting calendar was plagued by cancellations and postponements, but the Olympic goal was still alive and well. This situation caused concern as athletes from other countries continued their training without restrictions while athletes from Spain feared that their performance would suffer due to the unequal conditions. Faced with the postponement, on the one hand, they were relieved that conditions would be equal again, and on the other hand, they were sad to see another objective discarded from the competitive calendar. The emotional responses are similar to those found by Oblinger-Peters & Krenn (2020): confusion, disappointment and relief. Joaquín, an athlete who had overcome an injury, commented:

“When they decided that they were not going to be held, my mentality changed. It took me two or three days to get to grips with the fact that it wasn’t going to happen and I’d put in all that effort, especially to recover from an injury, eh, it’s not in vain, right?”

In this phase the motivation to train decreases due to the lack of goals. Alina explains:

“After they decided they were cancelling them and moving them to the following year, that second week was a bit of a downer because in the end it was a bit like: “Ugh, what am I training for now if we don’t know when there are going to be competitions?”

The third phase was coded as “Acceptance and Opportunity”and shows the process of adapting to concurrent transitions. In this phase most athletes, with the support of their coaches, managed to set short-term goals and changed their assessment of lockdown and postponement from one of threat into one of opportunity. They prioritised other aspects of their lives (e.g. studies, career development, family) and took advantage of training at home to partake in training activities that habitually, due to lack of time, they are not able to do. Ignasi commented:

“We saw it like this: you can gain strength, you can gain flexibility if you stretch every day, you have a lot of time to work on flexibility, which sometimes we don’t have time for on a daily basis.”

The present results show that the psychological resources of sport identity (i.e., frustration tolerance, adaptability), resources related to the environment (i.e., coaches, family and centre agents) and the development of extra-sport identities (i.e., studies, professional development) have operated as facilitating factors in coping with and managing these concurrent transitions. In turn, the results add the perception of lifestyle as a resource for adapting to the demands of lockdown. Ignasi commented:

“I think that in situations like this, which are a bit exceptional, sportsmen and women are able to cope well. Even better than other people because we are actually more exposed to situations that are extraordinary. In competitions anything can happen and you have to know how to deal with it. I think, and I’m speaking generally, that we athletes are people who [laughs] often face restrictions, basically.”

It is also at this stage that some athletes reported to have reflected on the role of sport, not only in their lives, but also in society. They also reflected on their identity. In this respect, the present results mirror those of Schinke et al. (2020) who argue that any unforeseen transition conceals the possibility of personal enrichment. Taking distance from the exacting demands of the sporting world allowed for the development of personal identity and the exploration of interests outside sport. Joaquín shared:

“I mean, I can describe myself without saying I’ve been an Olympian, I’ve been to a World Cup, I’ve been [a sporting discipline]. You know? It has made me reflect on that. You are not just that! You are more than that!”

The last sub-theme was coded as “Light at the end of the tunnel”and coincides with the relaxation of lockdown, and the possibility of leaving home for outdoor training. The government decreed that DAN athletes were permitted longer training slots than the rest of the population. The possibility of training outdoors increased their motivation and enabled them to regain experiences that could not be replicated through training at home. Those who participated in water sports were particularly interested in regaining these experiences, as they had never before been away from their environment – the water – for such a long time. After returning to the sea Aina commented: “It’s incredible, I mean, I don’t know, I really wanted to go back and in fact, well, I trained and then it’s true that I floated around for a while.” Figure 2 summarises the phases described above with their sub-themes and codes.

Ruffault et al. (2020) found that athletes who continued training at home and maintained the dynamics of interaction with the technical team generated the ideal conditions for return to sport, reducing anxiety levels and remaining intrinsically motivated. The present results coincide, but the differences between sports need to be considered (i.e., aquatic and non-aquatic), on the basis that those who depend on aquatic environments for their sporting activities have never had to spend so many days away from the water. As a result, they highlighted the uncertainty of how long it would take for them to recover their fitness as a concern.

Prospective analysis

Below are the codes, sub-themes and topics defined on the basis of expectations for the Post-Lockdown phase and concerns regarding the Olympic Games, scheduled to take place in 2021.

Post-lockdown

In asking athletes to tell us what they envisaged the post-lockdown phase to be like, most participants highlighted: (a) concern about the global impact of COVID-19 (e.g. deaths, economic crisis, unemployment), (b) uncertainty about the sporting calendar, Joan commented:

“[…] we don’t have the assurances we had last year (2019). Last year, well, you could plan from September until the Spanish Championships, for example. Because you knew that everything was going to be able to go ahead. But this year (.) we don’t know.”

(c) Concern about the duration of COVID-19 and (d) the expectation to return to training at the centre and adapt to the new health and safety regulations and protocols. In relation to the latter, Isona commented:

“It’s going to be weird at first, isn’t it? A lot of care, a lot of control, but I think the ability to adapt, especially for athletes, is very high. Once we’ve done it a few times we’ll get used to the fact that this is what we have to do and that these are the measures we have to take and we’ll do it.”

Tokyo 2020 + 1

Most athletes agreed that the Tokyo 2020 + 1 Olympic Games will have an added value, given that in addition to the usual barriers they have to overcome within the Olympic cycle, this time they have also overcome the COVID-19 barrier. Projecting what the road to Tokyo 2020 + 1 might look like, Berta shared:

“The road there will be a bit of a déjà vu because, of course, I’ve already completed the season. You know? Now repeating it is like a second chance, because this time things are clearer to me.”

As in the results of Clemente-Suárez et al. (2020), no negative perception of the impact of lockdown on performance in the run-up to Tokyo 2020 was found in the present study.

Considering the three scenarios proposed by Stambulova et al. (2020b), the present results show that uncertainty and concern about the evolution of COVID-19 and the potential cancellation of the Olympic Games, were even stronger in those who see Tokyo 2020 as the final stages of their sporting careers, and even their last or only chance of Olympic participation. Robert said:

“If the Olympic Games had taken place in 2020, depending on how things turned out there, I would have considered certain areas of my future and my sporting career, but imagine if they were cancelled! I certainly don’t know where I could find the energy… Yikes! The way I see it is that I’ve given it my all, I’ve come close once and all of a sudden that dream is gone.”

The results of the present study are in line with Hakansson et al. (2021) who warn of the need to consider not only the acute impact of concurrent transitions, but also the cumulative and prolonged impact of the pandemic and the postponement of the Olympic Games on the psychological well-being of athletes.

Conclusions

The results of this qualitative study offer further evidence for understanding the experiences of Olympic hopefuls in relation to the disruption of the Olympic cycle (i.e., lockdown and postponement of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games). The retrospective exploration of lockdown and prospective exploration of postponement have allowed an overview of the different events that make up these transitions. The announcement of the postponement of the Olympic Games was acknowledged as a milestone that changed the experience of lockdown, transforming the perception of lockdown from a threat into an opportunity. A number of resources that facilitated coping and adaptation to these transitions were also identified. These include psychological resources specific to sport identity (e.g. frustration tolerance, adaptability), environmental resources (e.g. coaches and other centre staff, rights as top athletes), lifestyle resources (e.g. habituation to training camps) and the development of extra-sporting identities (e.g. studies, professional development).

Exploring the prospective vision allowed possible focuses of intervention by sport psychology professionals to be detected, contemplating the impact of the prolongation of the pandemic. At the same time, it is understood that the disruption of the Olympic cycle can be seen as another opportunity to train athletes to deal with unexpected situations. By considering the stage of their sporting careers, athletes can be helped to make decisions about fighting, fleeing or coping with the demands of these transitions.

This study makes the relevant contributions described above and is not without its limitations. Primarily, considering the pragmatic nature of the project and the interpretative nature of this particular study, the commitment to the confidentiality of the participating athletes necessarily resulted in the omission of some information that could be interesting for the people who read the article, this limits the transferability of this information to other similar sporting contexts, as well as the applied use that can be made by sport science professionals.

Finally, future research could focus on: (a) longitudinally exploring the disruption of the Olympic cycle, (b) exploring the experience of the surrounding actors (i.e. coaches, families) and (c) exploring the post-Olympic transition in this particular cycle.

Acknowledgements

This work has been carried out thanks to the contribution of two research projects. Firstly, the project “Healthy Dual Careers” (HeDuCa) which has been supported by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (reference RTI2018-095468-B-100), Spain. Additionally, thanks to the project: “Athletes’ and sport entourage’s longitudinal experiences on the disruption of the Olympic cycle of Tokyo 2020” supported by the Olympic Studies Centre of the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

Special thanks to all the participants in this study for allowing the researchers to investigate their experiences, enabling mental health professionals to understand how to help them cope with unexpected situations. We would also like to thank Marina García, Dorottya Molnár, José Mejías, Anna Jordana and Marta Borrueco for their collaboration in transcribing the interviews.

References

[1] Bassi-Follari, J. (2015). Gail Jefferson’s transcription code: adaptation for its use in social sciences research. Quaderns de Psicologia, 17, 39. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.1252

[2] Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589-597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

[3] Brooks, S., Webster, R., Smith, L., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 395(10227), 912-920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

[4] Clemente-Suárez, V., Fuentes-García, J., de la Vega Marcos, R., & Martínez Patiño, M. (2020). Modulators of the Personal and Professional Threat Perception of Olympic Athletes in the Actual COVID-19 Crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1985. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01985

[5] Constandt, B., & Willem, A. (2021) Hosting the Olympics in Times of a Pandemic: Historical Insights from Antwerp 1920, Leisure Sciences, 43 (1-2), 50-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1773982

[6] Håkansson, A., Moesch, K., Jönsson, C., & Kenttä, G. (2021). Potentially Prolonged Psychological Distress from Postponed Olympic and Paralympic Games during COVID-19—Career Uncertainty in Elite Athletes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 (1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010002

[7] Henriksen, K., Schinke, R., McCann, S., Durand-Bush, N., Moesch, K., Parham, W. D., Larsen, H. L., Cogan, K., Donaldson, A., Poczwardowski, A., Hunziker, J., & Noce, F. (2020a). Athlete mental health in the Olympic/Paralympic quadrennium: a multi-societal consensus statement. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(3), 391-408. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2020.1746379

[8] Henriksen, K., Schinke, R., Noce, F., Poczwardoski, A., & Si, G. (2020b). Working with athletes during a pandemic and social distancing. The International Society of Sport Psychology (ISSP). https://www.issponline.org/images/isspdata/latest_news/ISSP_Corona_Challenges_and_Recommendations.pdf

[9] Jordana, A., Torregrossa, M., Ramis Laloux, Y., & Latinjak, A. T. (2017). Retirada del deporte de élite: Una revisión sistemática de estudios cualitativos. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 26(4), 68-74.

[10] Oblinger-Peters, V., & Krenn, B. (2020). “Time for Recovery” or “Utter Uncertainty”? The Postponement of the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games Through the Eyes of Olympic Athletes and Coaches. A Qualitative Study. Frontiers in Psychology 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.610856

[11] Odriozola-González, P., Planchuelo-Gómez, Á., Irurtia-Muñiz, M., & de Luis-García, R. (2020). Psychological symptoms of the outbreak of the COVID-19 confinement in Spain. Journal of Health Psychology, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105320967086

[12] Palmi Guerrero, J., & Solé Cases, S. (2014). Psychology and Sports Injury: Current State of the Art. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 118, 23-29. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2014/4).118.02

[13] Pons J., Ramis Y., Alcaraz S., Jordana A., Borrueco M., & Torregrossa M. (2020) Where Did All the Sport Go? Negative Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Life-Spheres and Mental Health of Spanish Young Athletes. Frontiers in Psychology 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.611872

[14] Poucher, Z., Tamminen, K., Caron, J., & Sweet, S. (2020). Thinking through and designing qualitative research studies: A focused mapping review of 30 years of qualitative research in sport psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 163-186. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2019.1656276

[15] Prato, L., Alcaraz, S., Ramis, Y., & Torregrossa, M. (2020). Experiencias del entorno deportivo de origen al asesorar a esgrimistas migrantes. Pensamiento Psicológico, 18(2), 1-31. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/801/80164789004/html/

[16] Ruffault, A., Bernier, M., Fournier, J., & Hauw, N. (2020). Anxiety and Motivation to Return to Sport During the French COVID-19 Lockdown. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.610882

[17] Schinke, R., Papaioannou, A., Maher, C., Parham, W., Larsen, C., Gordin, R., & Cotterill, S. (2020) Sport psychology services to professional athletes: working through COVID-19, International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18 (4), 409-413. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2020.1766182

[18] Schlossberg, N. K. (1981). A Model for Analyzing Human Adaptation to Transition. The Counseling Psychologist, 9(2), 2-18.

[19] Smith, B., & McGannon, K. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101-121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

[20] Solanellas, F., & Camps, A. (2017). The Barcelona Olympic Games: Looking Back 25 Years On (1). Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 127, 7-26. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2017/1).127.01

[21] Stambulova, N. (2003). Symptoms of a crisis-transition: A grounded theory study. En N. Hassmen (Ed.), SIPF Yearbook (97– 109). Örebro, Sweden: Örebro University Press.

[22] Stambulova, N., Ryba, T., & Henriksen, K. (2020a). Career development and transitions of athletes: the International Society of Sport Psychology Position Stand Revisited. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2020.1737836

[23] Stambulova, N., Schinke, R., Lavallee, D., & Wylleman, P. (2020b). The COVID-19 pandemic and Olympic/Paralympic athletes’ developmental challenges and possibilities in times of a global crisis-transition. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2020.1810865

[24] Stambulova, N. B., & Wylleman, P. (2015). Dual career development and transitions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 1–3. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.05.003

[25] Taku, K., & Arai, H. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on Athletes and Coaches, and Their Values in Japan: Repercussions of Postponing the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 25 (8), 623-630. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2020.1777762

[26] Torregrossa, M., Chamorro, J. L., & Ramis, Y. (2016). Transition from junior to senior and promoting dual careers in sport: an interpretative review. Revista de Psicología Aplicada al Deporte y el Ejercicio Físico, 1, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5093/rpadef2016a6

[27] Torregrossa, M., Ramis, Y., Pallarés, S., Azócar, F., & Selva, C. (2015). Olympic athletes back to retirement: A qualitative longitudinal study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 50-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.03.003

[28] Wylleman, P., Reints, A., & Van Aken, S. (2012). Athletes’ perceptions of multilevel changes related to competing at the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(5), 687–692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.04.005

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: May 3, 2021

Accepted: October 26, 2021

Published: April 1, 2022

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en