Physical Exercise as an Adjunctive Treatment in Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review

*Corresponding author: Eva Parrado eva.parrado@uab.cat

Cite this article

Teixidor-Batlle, C., Parrado, E., & Ventura, C. (2025). Physical exercise as an adjunctive treatment in eating disorders: A systematic review.Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 163, 3-18. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2026/1).163.01

Abstract

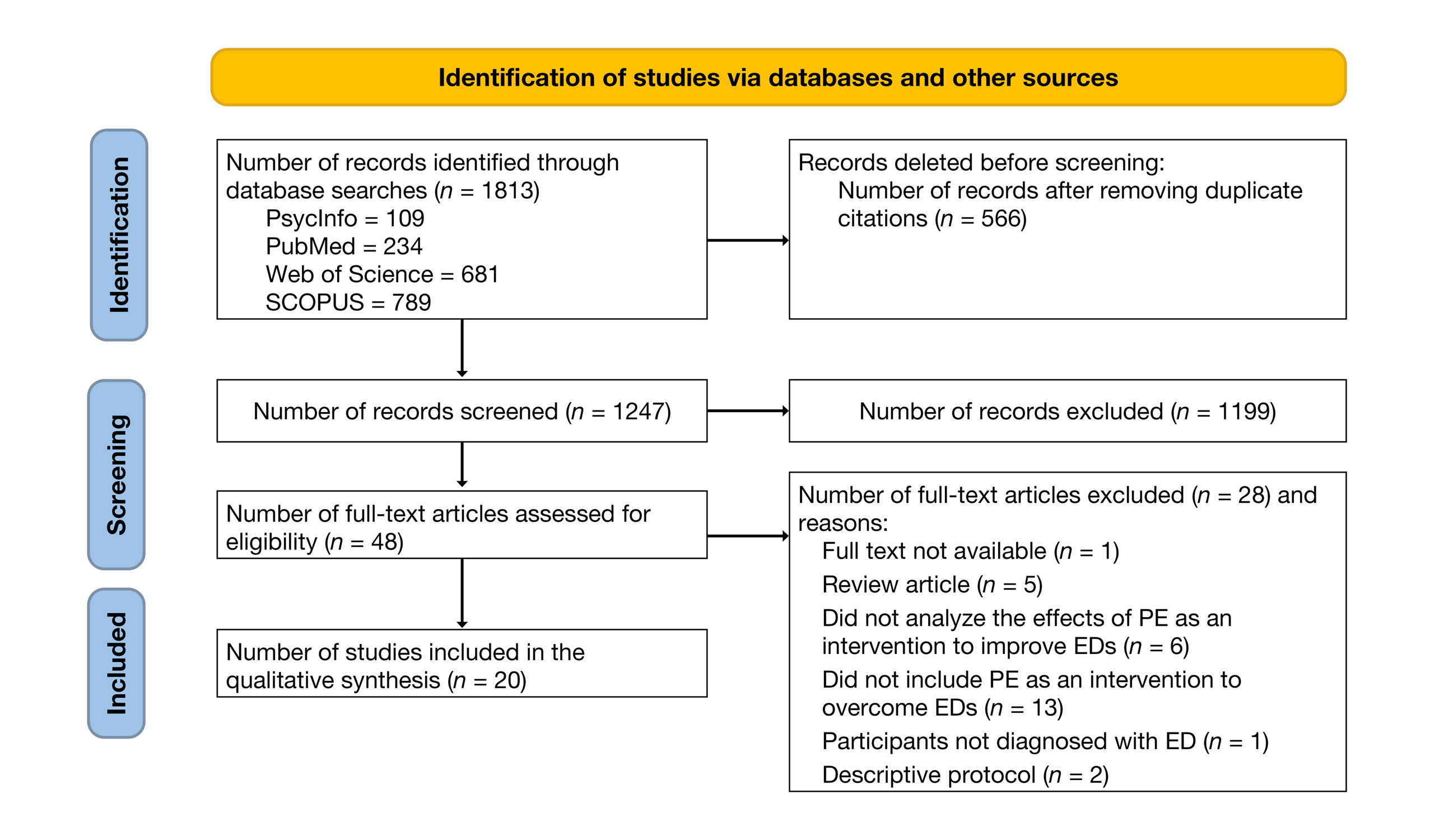

This systematic review aimed to identify the interventions carried out to date to assess the effectiveness of physical exercise (PE) as an adjunctive treatment for eating disorders (EDs). The main objectives of this systematic review were: (a) to identify which aspects—both symptomatological and physical—improve with the inclusion of PE in the treatment of EDs, and (b) to determine the characteristics that PE should have to improve the identified symptomatology. A literature search was conducted following PRISMA guidelines using the PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and Scopus databases. Keywords were divided into three groups (Eating disorders; Exercise and treatment; Characteristics of physical activity), and articles published between 2012 and 2022 were reviewed. Of the initial 1,247 results, 20 studies were included in the analysis, 10 of which were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Improvements were observed in muscle strength, aerobic capacity, BMI, bone density, as well as in ED symptomatology and quality of life. However, due to methodological differences among the exercise programs, it was not possible to determine the specific characteristics responsible for symptom improvement. Further research is needed to determine the frequency, intensity, duration, type, and volume of PE programs.

Introduction

It has been demonstrated that engaging in physical activity (PA) promotes the physical, psychological, and social well-being of participants (González-Peris et al., 2022). In recent years, scientific literature has increasingly focused on the therapeutic properties of physical exercise (PE) in addressing mental health issues. Eating disorders (ED), such as anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorder (BED), or other specified feeding or eating disorders (OSFED), are considered psychiatric conditions characterized by altered eating behaviors that impair health and psychosocial functioning (González-Peris et al., 2022). In several manifestations of these ED, patients use PA as a common strategy to lose weight, improve their figure (Quiles et al., 2021), compensate for or eliminate food intake, or to relieve negative states (anxiety, depression, and stress) and ED symptoms (concern about weight, drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction, and restrictive profiles). However, it has been shown that PE as an adjunctive treatment can have positive effects on the main symptoms of AN, on both physical and mental health, and can promote better engagement with healthcare teams (Quiles et al., 2021). In fact, the first studies on this topic, conducted by Blinder et al. (1970) and Beaumont et al. (1994), observed improvements in symptomatology after implementing a supervised PE program in groups of patients with EDs. Later research indicated that PE reduced compensatory behaviors and facilitated weight gain in anorexia, decreased drive for thinness, bulimic symptoms, and body dissatisfaction, increased strength levels, reversed cardiac abnormalities in severe anorexia, and improved quality of life (Calogero & Pedrotty, 2004; Cook et al., 2017; Fernández-del-Valle et al., 2014).

Interestingly, PE is still rarely used in mental health units as part of ED treatment due to concerns that it might reinforce excessive exercise aimed at achieving the “ideal body” (Quesnel et al., 2018). This is likely due to the absence of clear guidelines on how to manage PE in this context, the lack of standardized protocols guiding professionals on how to use exercise effectively as part of ED treatment, and differing attitudes toward these approaches in clinical settings (Fernández-del-Valle et al., 2014; Toutain et al., 2022).

Based on the above, the objectives of this systematic review were: (i) to identify which aspects, both symptom-related and physical fitness-related, improve with the inclusion of PE in the treatment of EDs, and (ii) to determine the characteristics that PE should have in treatment to improve the identified symptomatology.

Methodology

A systematic review of relevant literature was conducted following the PRISMA 2020 statement (Page et al., 2021). Due to the methodological and statistical heterogeneity of the included studies, a descriptive approach was adopted in the synthesis of the study (Rethlefsen et al., 2021).

Search strategy

A search of the relevant literature was conducted in four databases: PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and Scopus. The search strategy included both controlled vocabulary terms and free-text terms (see Table 1).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

For inclusion, the retrieved articles had to have been published between 2012 and 2022, in English and/or Spanish. The search was conducted on November 28, 2022. Systematic reviews, descriptive guides or intervention protocols, and studies that included samples of professional athletes were excluded.

Potential articles were selected based on a set of keywords defined through the PICOS strategy (Participants, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study design; Liberati et al., 2009) (see Table 2). The search initially focused on the title and abstract.

One reviewer (C.T.B.) carried out the data analysis and the search process in the main databases. All records identified electronically were evaluated by title and abstract. Duplicate articles were removed and considered only once. Full texts were obtained for all articles considered potentially eligible. Subsequently, the preselected records were independently examined by two reviewers (C.T.B. and C.V.), who selected the final studies to be included in the review. In case of disagreement, the opinion of a third reviewer (E.P.) was considered.

Results

Search results:

After excluding duplicate records, a total of 1,247 potentially relevant publications were considered eligible. Following title and abstract screening, 48 publications were selected for full-text review. Finally, 20 articles were included in this systematic review (Figure 1), 10 of which were randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Note. PE = Physical Exercise, ED = Eating Disorder.

Participant characteristics

The total number of participants across the different studies was 895. Table 3 details their characteristics.

Characteristics of the interventions

Among the twenty studies reviewed, the duration of the interventions ranged from one to twenty-six weeks. Tables 4 and 5 present, in alphabetical order, the main characteristics of all the reviewed studies.

Effects of physical exercise on ED symptomatology

Effects of physical exercise on physical condition

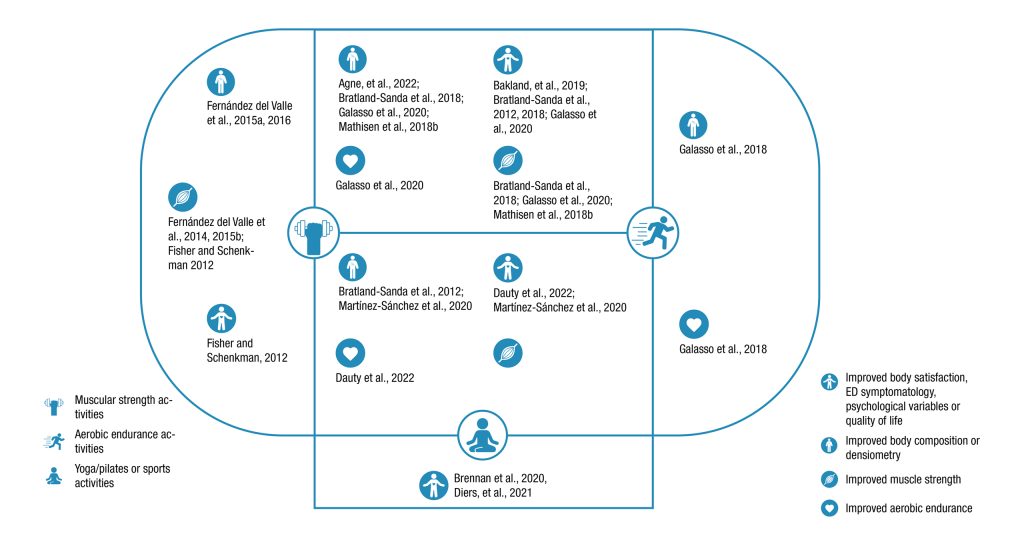

Thirteen articles analyzed the effects of PE on the physical condition of patients. Regarding physical condition and abilities, improvements were found in muscle strength of the upper and lower limbs (n = 6; Bratland-Sanda et al., 2012; Bratland-Sanda et al., 2018; Dauty et al., 2022; Fernández-del-Valle et al., 2014; Fernández-del-Valle et al., 2015b; Mathisen et al., 2018a); cardiorespiratory improvements (n = 3; Dauty et al., 2022; Galasso et al., 2018; Galasso et al., 2020); better balance test results (n = 1; Dauty et al., 2022); and improved agility (n = 2; Fernández-del-Valle et al., 2014; Fisher & Schenkman, 2012). With regard to anthropometric measures, significant improvements were observed in BMI (n = 7; Agne et al., 2022; Bratland-Sanda & Vrabel, 2018; Bratland-Sanda et al., 2018; Dauty et al., 2022; Galasso et al., 2018; Fernández-del-Valle et al., 2015a; Fernández-del-Valle et al., 2015b) and in skinfold thickness (n = 2; Agne et al., 2022; Fernández-del-Valle et al., 2015b).

Efficacy of physical exercise on ED symptomatology

Ten articles analyzed the effects of PE on ED symptomatology. One study included aerobic exercise (n =1; Galasso et al., 2018), reporting a decrease in pathological behaviors related to compulsive exercise (CE) and food intake.Another study examined the effects of strength-endurance training on the psychopathological symptoms of BN and BED and on CE-related pathological behaviors after the intervention (Mathisen et al., 2018b).

As for interventions combining strength training and aerobic activities (n = 3; Bakland et al., 2019; Bratland-Sanda et al., 2012; Galasso et al., 2020), a significant reduction was observed in the total score of the Eating Disorders Examination (EDE), as well as significant improvements in emotional and cognitive symptoms related to binge eating and a reduction in compensatory behaviors.

Regarding mind-body activities such as yoga (n = 2; Brennan et al., 2020; Diers et al., 2020) or Pilates (n = 1; Martínez-Sánchez et al., 2020), yoga reduced binge-eating frequency in individuals with BN, decreased emotional dysregulation and self-criticism, improved self-compassion and mindfulness skills, and significantly reduced body-image concerns. Pilates, on the other hand, improved sleep quality.

Other studies allowed participants to choose the type of PE they wished to practice (n = 2; Bratland-Sanda & Vrabel, 2018; Lampe et al., 2022). Both reported improvements in ED symptomatology, and one of them also found a reduction in overall psychological distress and a decrease in compulsive PE practice.

Discussion

This review provides evidence that physical exercise (PE) can serve as an effective therapeutic tool for patients diagnosed with an eating disorder (ED). It shows that the prescription of PE, when supervised by professionals and implemented by a multidisciplinary team, can be safe and offer multiple benefits for individuals with such disorders (Cook et al., 2016).

Improvements in ED symptomatology through the inclusion of PE in treatment

A total of 35% of the studies (n = 7) did not describe the intervention characteristics in sufficient detail (for example, the volume or intensity of PE), providing only general information about the type of PE (e.g., Bakland et al., 2019; Mathisen et al., 2018b). Furthermore, the instruments used to assess symptomatology were heterogeneous (e.g., EDE-Q [Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire], BITE [Bulimic Investigatory Test Edinburgh], BSQ [Body Shape Questionnaire], and semi-structured interviews), as each focused on different dimensions.

In this regard, in the present systematic review, the effectiveness of the interventions could not be determined based on specific improvements in ED symptomatology; it could only be examined according to the degree of adherence and the changes in reported outcomes obtained after the PE program. Nevertheless, even though the efficacy criteria were not standardized, only one study concluded that including PE in the treatment for EDs was not more or equally effective in experimental groups compared to CG (Mathisen et al., 2018b).

In this case, as the authors themselves point out, the lack of significant differences could be due to the low statistical power resulting from the small sample size and the high dropout rate in the control group. The remaining studies concluded that prescribed exercise provided greater efficacy.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the results indicated both psychological and physical benefits after performing PE as part of ED treatment. Consequently, the findings suggest that PE therapy for patients with EDs (AN, BN, BED, or OSFED) is safe and beneficial for both ED symptomatology and overall physical and mental health, although identifying a single specific type of PE remains challenging (Mathisen et al., 2023; Toutain et al., 2022). In this regard, strength training targeting major muscle groups showed significant increases in strength based on the 5RM test after 16 weeks of weight training and the 70% 6RM test after 8 weeks (Bratland-Sanda et al., 2018; Fernández-del-Valle et al., 2014). Previous reviews involving AN patients have also confirmed improvements in muscle strength through PE with resistance training, both with and without weights, after 12 weeks of training, and through bench press and leg press tests following 8 weeks of high-intensity strength training (Miñano-Garrido et al., 2022).

More specifically, Vancampfort et al. (2014b) concluded that a program combining aerobic and strength-endurance training for patients with AN and BN resulted in increased muscle strength, BMI, and body fat percentage. Similar findings were observed in non-clinical samples. Recent review studies, such as Mikkonen et al. (2024), indicate that regular strength and endurance training leads to gains in both strength and endurance capacity in healthy adult women.

However, in addition, a combined program including aerobic exercise, yoga, and basic body-awareness therapy in patients with AN and BN promoted reductions in eating disorder symptomatology and depressive symptoms. Notably, this review identified a larger number of studies analyzing the benefits of strength and aerobic-resistance training. It is particularly important to highlight the difficulty and complexity of performing aerobic exercise in patients with AN, since excessively intense activity—especially aerobic modalities such as running or swimming—may be inappropriate for individuals with severe malnutrition due to its high energy expenditure requirements, which could lead to further weight loss or other medical risks (Heinl, 2018). Moreover, aerobic PE is generally avoided in the care of patients with AN, as they often show a strong drive for physical activity and an inability to remain still—commonly referred to as a “drive for activity.”

It should be noted that although, in individuals with an ED, the goal is usually to restore BMI by increasing it, Galasso et al. (2018) reported an improvement in aerobic capacity but also a reduction in BMI, possibly because the sample consisted of patients diagnosed with BED who presented obesity (BMI ≥ 30). Similarly, Martínez-Sánchez et al. (2020) found no changes in body composition or physical condition after the Pilates program, although they did observe a slight increase in BMI percentile among women with higher weight. This was likely because the participants were adolescents and possibly in a period of restoration and stabilization of body composition, so Pilates helped maintain this stability. In fact, Kibar et al. (2016) found that an 8-week Pilates program in healthy women had beneficial effects on muscle strength (abdominal and lumbar), as well as on static balance and flexibility. It should also be noted that the present review did not identify physical changes after Pilates or yoga interventions, as the variables evaluated in these studies focused on behavioral aspects rather than physical condition (Brennan et al., 2020; Diers et al., 2020).

At the physiological level, as in healthy women (Hsu et al., 2024), PE was also found to improve bone health in women with EDs, who often show low bone mineral density (BMD), deteriorated bone structure, and reduced bone strength (Bratland-Sanda et al., 2018; Mathisen et al., 2018b)—effects that may be further worsened by the negative influence of antidepressants (DiVasta et al., 2017). It will be important to take BMD values into account, as low levels increase the risk of osteoporosis and, consequently, the likelihood of experiencing pain and fractures in adulthood (Lopes et al., 2022).

Among the experimental studies in this review, a reduction was recorded in compulsive exercise, the drive for thinness, and bulimic symptoms in ED patients who engaged in PE. Improvements were also observed in body satisfaction (Bakland et al., 2019; Bratland-Sanda & Vrabel, 2018; Diers et al., 2020), as well as in mood, quality of life, and well-being (Agne et al., 2022; Bakland et al., 2019; Brennan et al., 2020; Vancampfort et al., 2014a). The mental benefits and improvements in pathological behaviors related to CE reported by Bakland et al. (2019) and Mathisen et al. (2018b) were likely due to the fact that therapeutic exercise treatment can help reduce patients’ anxiety and “drive for thinness,” decrease compulsive engagement in exercise, provide enjoyment, and contribute to better mood and body image (Cook et al., 2011; Vancampfort et al., 2014b).

Characteristics of PE for improving ED symptomatology in treatment

This review revealed substantial variability and a lack of systematization in PE prescription—similar to the findings of the systematic review by Moola et al. (2013)—making it difficult to determine specific characteristics or guidelines for incorporating PE into ED treatment.

Focusing on training variables, and specifically on external load, these were heterogeneous. Regarding intensity and volume in strength training, most programs applied moderate loads (around 50% of 1RM or 70% of 6RM, with 6–15 repetitions and 1–5 sets; Agne et al., 2022; Fernández-del-Valle et al., 2015a). For strength-endurance training, loads were not specified (Mathisen et al., 2018b), while for range-of-motion exercises, work durations of 15–60 seconds and 2–4 sets were reported (Dauty et al., 2022; Fisher & Schenkman, 2012). On the other hand, similarities were found in the strength exercises included, as most involved multi-joint movements and large muscle groups (e.g., seated row, bench press, leg press, leg extension, lat pulldown, trunk curl, back extension, and push-ups; Bratland-Sanda et al., 2018; Fernández-del-Valle et al., 2015a). As for aerobic activity, the interventions were much more diverse, both in activity type (e.g., varied sports; Dauty et al., 2022) and in structure—pyramidal intervals (Bakland et al., 2019), high-intensity intervals (Mathisen et al., 2018b)—and in external load. Despite this heterogeneity, the programs produced beneficial effects.

Cook et al. (2016) concluded that tailoring the exercise mode to individual needs is one of the most therapeutically important principles. Therefore, applying the principle of individualization is key, including the type of exercise itself. In this sense, authors such as Bratland-Sanda and Vrabel (2018), Lampe et al. (2022), or Vancampfort et al. (2014a) allowed participants to choose their preferred activity type and found improvements in ED psychopathology and quality of life, likely due to increased motivation to engage in enjoyable activities. It is important to note that factors such as enjoyment, motivation, choice, social interaction, and sense of belonging (White et al., 2018) also influence the relationship between physical activity and mental health.

On the other hand, mind-body interventions (e.g., pilates or yoga) have also been used as treatment in EDs, as they appear to positively influence body image and reduce ED symptomatology (Hall et al., 2016; Vancampfort et al., 2014a). In fact, Sánchez and Munguía-Izquierdo (2017) stated that yoga has the potential to promote body self-awareness—that is, the ability to experience the body from within through meditation, physical movement, and breathing.

The heterogeneity of PE characteristics identified in this review may also be explained by the inclusion of various ED diagnoses (AN, BN, OSFED, and BED), unlike previous reviews that focused on a single manifestation (Toutain et al., 2022). The spectrum of eating-related behavior differs depending on diagnosis, suggesting that each ED type requires a specific exercise prescription adapted to its particularities.

Given all the above and the difficulty of determining common PE guidelines for ED patients, it is proposed that before initiating exercise in these individuals, it is necessary to reconsider what physical activity means to them, as the personal meaning of PE must change (Cook et al., 2016). The goal is not to eliminate exercise from daily life but to educate the person to understand movement as a complement to psychotherapy or nutrition. Thus, when individuals return to the gym or resume PE after recovery, they will perceive the activity as enjoyable and healthy. If this shift in perspective is not addressed, there is also a risk that the ED may become chronic (Rizk et al., 2020) or that maladaptive exercise patterns may increase the risk of injury. For these reasons, and as a final conclusion, PE should not be withdrawn from ED patients but rather adapted and ensured to be carried out under supervision and with the approval of both a therapist and a qualified exercise professional.

Limitations

Despite the contributions of the present work, some limitations should be mentioned. On the one hand, in some cases the studies did not specify what type of stimuli were used or provided little detail regarding the training variables applied to the patient. On the other hand, the heterogeneity of the interventions in terms of analyzed variables, content, duration, and assessment timing made it difficult to compare the results among studies, highlighting the need for further research. Likewise, in order to obtain a substantial number of articles for the review, studies with different methodological designs were included, many of them with limited sample sizes and heterogeneous use of assessment measures and instruments.

Conclusions

This systematic review summarizes the evidence that participation in structured PE programs (aerobic endurance, muscle strength, strength-endurance, or yoga exercises) can be highly beneficial for this clinical population, as it reduces ED symptomatology, improves quality of life and psychological well-being, increases muscle strength and cardiorespiratory capacity, and enhances BMD and anthropometric measures. However, there is still insufficient research to develop a systematic and standardized methodology for prescribing PE as an adjunctive treatment for EDs. Moreover, the inclusion of various ED manifestations in this review made it difficult to identify specific and common guidelines, since each type presents unique nuances and characteristics. For this reason, in future work we aim to analyze and detail the reviewed studies individually, focusing on the similarities according to the type of ED, specifically AN, BN, and BED.

Along the same lines, this also makes it difficult to determine the specific characteristics that PE should have for this population. It has been shown that structured PE programs—including aerobic endurance, muscle strength, strength-endurance, or yoga exercises—significantly improve symptomatology. In general terms, the interventions that have improved the physical or mental symptomatology of individuals diagnosed with EDs are based on the use of light to moderate loads, both for strength and for aerobic endurance, progressively increased while respecting the principle of individualization.

Acknowledgements

This work has been carried out thanks to the project PID2019-107473RB-C2 of the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of the Government of Spain and thanks to the project 2021SGR-00806 of the Government of Catalonia.

References

[1] American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). (2018). ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. (10th Ed.) Wolters Kluwer

[2] American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. (5th Ed.) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association

[3] Agne, A., Quesnel, D. A., Larumbe-Zabala, E., Olmedillas, H., Graell-Berna, M., Pérez-Ruiz, M., & Fernández-del-Valle, M. (2022). Progressive resistance exercise as complementary therapy improves quality of life and body composition in anorexia nervosa: A randomized controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 48. doi.org/10.1016/J.CTCP.2022.101576

[4] Bakland, M., Rosenvinge, J. H., Wynn, R., Sundgot-Borgen, J., Fostervold Mathisen, T., Liabo, K., Hanssen, T.A. & Pettersen, G. (2019). Patients’ views on a new treatment for Bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder combining physical exercise and dietary therapy (the PED-t). A qualitative study. Eating Disorders, 27(6), 503–520. doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2018.1560847

[5] Beumont, P. J., Arthur, B., Russell, J. D., & Touyz, S. W. (1994). Excessive physical activity in dieting disorder patients: proposals for a supervised exercise program. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 15(1), 21–36. doi.org/10.1002/1098-108x(199401)15:13.0.co;2-k

[6] Blinder, B. J., Freeman, D. M., & Stunkard, A. J. (1970). Behavior therapy of anorexia nervosa: effectiveness of activity as a reinforcer of weight gain. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 126(8), 1093–1098. doi.org/10.1176/ajp.126.8.1093

[7] Bratland-Sanda, S, & Vrabel, K. A. (2018). An investigation of the process of change in psychopathology and exercise during inpatient treatment for adults with longstanding eating disorders. Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(1). doi.org/10.1186/s40337-018-0201-7

[8] Bratland-Sanda, Solfrid, Martinsen, E. W., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2012). Changes in Physical Fitness, Bone Mineral Density and Body Composition During Inpatient Treatment of Underweight and Normal Weight Females with Longstanding Eating Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research dnd Public Health, 9(1), 315–330. doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9010315

[9] Bratland-Sanda, Solfrid, Overby, N. C., Bottegaard, A., Heia, M., Storen, O., Sundgot-Borgen, J., & Torstveit, M. K. (2018). Maximal Strength Training as a Therapeutic Approach in Long-Standing Anorexia Nervosa: A Case Study of a Woman With Osteopenia, Menstrual Dysfunction, and Compulsive Exercise. Clinical Case Studies, 17(2), 91–103. doi.org/10.1177/1534650118755949

[10] Brennan, M. A., Whelton, W. J., & Sharpe, D. (2020). Benefits of yoga in the treatment of eating disorders: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Eating Disorders, 28(4), 438–457. doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2020.1731921

[11] Calogero, R. M., & Pedrotty, K. N. (2004). The practice and process of healthy exercise: an investigation of the treatment of exercise abuse in women with eating disorders. Eating Disorders, 12(4), 273–291. doi.org/10.1080/10640260490521352

[12] Cook, B., Hausenblas, H., Tuccitto, D., & Giacobbi, P. R. (2011). Eating disorders and exercise: A structural equation modelling analysis of a conceptual model. European Eating Disorders Review, 19(3), 216–225. doi.org/10.1002/erv.1111

[13] Cook, B., & Leininger, L. (2017). The ethics of exercise in eating disorders: Can an ethical principles approach guide the next generation of research and clinical practice?. Journal of sport and health science, 6(3), 295–298. doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2017.03.004

[14] Cook, B. J., Wonderlich, S. A., Mitchell, J. E., Thompson, R., Sherman, R., & McCallum, K. (2016). Exercise in Eating Disorders Treatment: Systematic Review and Proposal of Guidelines. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 48(7), 1408–1414. doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000912

[15] Dauty, M., Menu, P., Jolly, B., Lambert, S., Rocher, B., Le Bras, M. Jirka, A., Guillaut, P., Pretagut, S. & Fouasson-Chailloux, A. (2022). Inpatient Rehabilitation during Intensive Refeeding in Severe Anorexia Nervosa. Nutrients, 14(14). doi.org/10.3390/nu14142951

[16] Diers, L., Rydell, S. A., Watts, A., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2020). A yoga-based therapy program designed to improve body image among an outpatient eating disordered population: program description and results from a mixed-methods pilot study. Eating disorders, 28(4), 476–493. doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2020.1740912

[17] DiVasta, A. D., Feldman, H. A., O’Donnell, J. M., Long, J., Leonard, M. B., & Gordon, C. M. (2017). Effect of Exercise and Antidepressants on Skeletal Outcomes in Adolescent Girls WithAnorexia Nervosa. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(2), 229–232. doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.10.003

[18] Fernández-del-Valle, M., Larumbe-Zabala, E., Graell-Berna, M., & Perez-Ruiz, M. (2015a). Anthropometric changes in adolescents with anorexia nervosa in response to resistance training. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia Bulimia and Obesity, 20(3), 311–317. doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0181-4

[19] Fernández-del-Valle, M., Larumbe-Zabala, E., Morande-Lavin, G. & Perez Ruiz, M., (2015b). Muscle function and body composition profile in adolescents with restrictive anorexia nervosa: does resistance training help?. Disability and Rehabilitation, 38(4), 346–353. doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1041612

[20] Fernández-del-Valle, M., Larumbe-Zabala, E., Villaseñor-Montarroso, A., Cardona Gonzalez, C., Diez-Vega, I., Lopez Mojares, L. M. & Pérez Ruiz, M. (2014). Resistance training enhances muscular performance in patients with anorexia nervosa: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(6), 601–609. doi.org/10.1002/eat.22251

[21] Fisher, B. A., & Schenkman, M. (2012). Functional recovery of a patient with anorexia nervosa: Physical therapist management in the acute care hospital setting. Physical Therapy, 92(4), 595–604. doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20110187

[22] Galasso, L., Montaruli, A., Bruno, E., Pesenti, C., Erzegovesi, S., Cè, E., Coratella, G., Roveda, E. & Esposito, F. (2018). Aerobic exercise training improves physical performance of patients with binge-eating disorder. Sport Sciences for Health, 14(1), 47–51. doi.org/10.1007/s11332-017-0398-x

[23] Galasso, L., Montaruli, A., Jankowski, K. S., Bruno, E., Castelli, L., Mulè, A., Chiorazzo, M., Ricceri, A., Erzegovesi, S., Caumo, A., Roveda, E. & Esposito, F. (2020). Binge eating disorder: What is the role of physical activity associated with dietary and psychological treatment? Nutrients, 12(12), 1–11. doi.org/10.3390/nu12123622

[24] González-Peris, M., Peirau, X., Roure, E., Violán, M. (2022). Guia de prescripció d’exercici físic per a la salut. 2a ed. Barcelona: Generalitat de Catalunya.

[25] Hall, A., Ofei-Tenkorang, N. A., Machan, J. T., & Gordon, C. M. (2016). Use of yoga in outpatient eating disorder treatment: A pilot study. Journal of Eating Disorders, 4(1), 38. doi.org/10.1186/s40337-016-0130-2

[26] Heinl, K. (2018). The Influence of Physical Activity or Exercise Interventions on Physiological and Psychological Conditions of People with Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review. (Doctoral Thesis, University of Bayreuth). www.grin.com/document/452114

[27] Hsu, H. H., Chiu, C. Y., Chen, W. C., Yang, Y. R., & Wang, R. Y. (2024). Effects of exercise on bone density and physical performance in postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. PM&R., 1–26. doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.13206

[28] Kibar, S., Yardimci, F. Ö., Evcik, D., Ay, S., Alhan, A., Manço, M., & Ergin, E. S. (2016). Can a pilates exercise program be effective on balance, flexibility and muscle endurance? A randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 56(10), 1139–1146. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26473443

[29] Lampe, E. W., Forman, E. M., Juarascio, A. S., & Manasse, S. M. (2022). Feasibility, Acceptability, and Preliminary Target Engagement of a Healthy Physical Activity Promotion Intervention for Bulimia Nervosa: Development and Evaluation via Case Series Design. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 29(3), 598–613. doi.org/10.1016/J.CBPRA.2021.05.006

[30] Liberati, A., Altman, D., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P., Ioannidis, J., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P.J., Kleijnen, J. & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine®, 151(4) 65–94. doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136

[31] Lopes, M. P., Robinson, L., Stubbs, B., dos Santos Alvarenga, M., Araújo Martini, L., Campbell, I. C., & Schmidt, U. (2022). Associations between bone mineral density, body composition and amenorrhoea in females with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(1), 1–28. doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00694-8

[32] Martin, S. P. K., Bachrach, L. K., & Golden, N. H. (2017). Controlled Pilot Study of High-Impact Low-Frequency Exercise on Bone Loss and Vital-Sign Stabilization in Adolescents With Eating Disorders. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(1), 33–37. doi.org/10.1016/J.JADOHEALTH.2016.08.028

[33] Martínez-Sánchez, S. M., Martinez-Garcia, T. E., Bueno-Antequera, J. & Munguia-Izquierdo, D. (2020). Feasibility and effect of a Pilates program on the clinical, physical and sleep parameters of adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 39. doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101161

[34] Mathisen, T. F., Sundgot-Borgen, J., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Bratland-Sanda, S. (2018a). Managing risk of non-communicable diseases in women with bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorders: A randomized trial with 12 months follow-up. Nutrients, 10(12). doi.org/10.3390/nu10121887

[35] Mathisen, T. F., Bratland-Sanda, S., Rosenvinge, J. H., Friborg, O., Pettersen, G., Vrabel, K. A., & Sundgot-Borgen, J. (2018b). Treatment effects on compulsive exercise and physical activity in eating disorders. Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(1). doi.org/10.1186/s40337-018-0215-1

[36] Mathisen, T. F., Hay, P., & Bratland-Sanda, S. (2023). How to address physical activity and exercise during treatment from eating disorders: a scoping review. Current opinion in psychiatry, 36(6), 427–437. doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000892

[37] Mikkonen, R. S., Ihalainen, J. K., Hackney, A. C., & Häkkinen, K. (2024). Perspectives on concurrent strength and endurance training in healthy adult females: A systematic review. Sports Medicine, 54(4), 673–696. doi.org/10.1007/s40279-023-01955-5

[38] Minano-Garrido, E. J., Catalan-Matamoros, D., & Gómez-Conesa, A. (2022). Physical Therapy Interventions in Patients with Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 13921. doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113921

[39] Moola, F. J., Gairdner, S. E., & Amara, C. E. (2013). Exercise in the care of patients with anorexia nervosa: a systematic review of the literature. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 6(2), 59-68. doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2013.04.002

[40] Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C, Welch, V.A., Whiting, P. & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS medicine, 18(3), e1003583. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583

[41] Quesnel, D. A., Libben, M., D. Oelke, N., I. Clark, M., Willis-Stewart, S., & Caperchione, C. M. (2018). Is abstinence really the best option? Exploring the role of exercise in the treatment and management of eating disorders. Eating Disorders, 26(3), 290–310. doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2017.1397421

[42] Quiles, Y., León, E., & López López, J. A. (2021). Effectiveness of exercise‐based interventions in patients with anorexia nervosa: A systematic review. European Eating Disorders Review, 29(1), 3–19. doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2789

[43] Rethlefsen, M. L., Kirtley, S., Waffenschmidt, S., Ayala, A. P., Moher, D., Page, M. J., & Koffel, J. B. (2021). PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Systematic reviews, 10(1), 1–19. doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01542-z

[44] Rizk, M., Mattar, L., Kern, L., Berthoz, S., Duclos, J., Viltart, O. & Godart, N. (2020). Physical Activity in Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 12(1). doi.org/10.3390/nu12010183

[45] Sánchez, S. M. M., & Munguia-Izquierdo, D. (2017). Physical exercise as a tool for the treatment of eating disorders. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 4(1), 339–350. doi.org/10.17060/ijodaep.2017.n1.v4.1062

[46] Toutain, M., Gauthier, A., & Leconte, P. (2022). Exercise therapy in the treatment of anorexia nervosa: Its effects depending on the type of physical exercise-A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.939856

[47] Vancampfort, D., Probst, M., Adriaens, A., Pieters, G., De Hert, M., Stubbs, B., Soundy, A. & Vanderlinden, J. (2014a). Changes in physical activity, physical fitness, self-perception and quality of life following a 6-month physical activity counseling and cognitive behavioral therapy program in outpatients with binge eating disorder. Psychiatry Research, 219(2), 361–366. doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.016

[48] Vancampfort, D., Vanderlinden, J., De Hert, M., Soundy, A., Adámkova, M., Skjaerven, L. H., Catalán-Matamoros, D., Gyllensten, A.L., Gómez-Conesa, A. & Probst, M. (2014b). A systematic review of physical therapy interventions for patients with anorexia and bulemia nervosa. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36(8), 628–634. doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.808271

[49] White, R. L., Olson, R., Parker, P. D., Astell-Burt, T., & Lonsdale, C. (2018). A Qualitative Investigation of the Perceived Influence of Adolescents’ Motivation on Relationships between Domain-Specific Physical Activity and Positive and Negative Affect. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 14, 113-120. doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2018.03.002

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: December 20, 2024

Accepted: April 29, 2025

Published: January 1, 2026

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en