Muscle Strength Training in Fibromyalgia Patients. Literature Review

*Corresponding author: María Cristina Enríquez Reyna maria.enriquezryn@uanl.edu.mx

Cite this article

Bañuelos-Terés, L. E., Enríquez-Reyna, M. C., Hernández-Cortés, P. L., & Ceballos-Gurrola, O. (2022). Muscle Strength Training in Fibromyalgia Patients. Literature Review. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 149, 1-12.

https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2022/3).149.01

Abstract

People with fibromyalgia (FM) suffer from chronic pain and other symptoms, which affect muscle strength and quality of life. The aim of the present review was to describe the characteristics of training programmes that assessed any strength-related variables in people with FM, specifically regarding prescription, findings, participant retention and research team. The search was carried out in the Cochrane, Medline and Redalyc databases, using the keywords: fibromyalgia and strength training. Experimental studies published from 2016 to 2020 were included, of which 16 articles were processed. The main findings were that this type of training was useful and safe, impacting pain control, while improving individual physical condition and functionality. Moreover, the estimated programme adherence rate was above 73% in most publications. Similarly, the programmes evaluated suggested participant acceptance and the achievement of favourable results in the short term. Lastly, it is important to note that the integration of the multidisciplinary team was a constant in this type of project.

Introduction

Fibromyalgia [FM] is an idiopathic disease characterised by widespread chronic pain (Wong et al., 2018), accompanied by a series of symptoms such as sleep disorder, fatigue, excessive anxiety, depression (Andrade et al., 2017a), irritable bowel (Silva et al., 2019), stiffness, and memory-linked problems, attention and ability to concentrate (Bair & Krebs, 2020; Collado-Mateo et al., 2017). This disease affects 3% of the world population (Wong et al., 2018) and is seen more frequently in women than in men, with a ratio of 8 to 1, in an age group between 35 and 60 years (Katz et al., 2010; Silva et al., 2019).

FM generates many expenses for patients due to frequent visits to the doctor (Collado-Mateo et al., 2017), with an average of up to 10 visits per year (Bair & Krebs, 2020). Moreover, due to sleep disorders and pain, patients report a low quality of life (Andrade et al., 2017a), often quit their jobs (Collado-Mateo et al., 2017) and lead a sedentary lifestyle, which causes their functional capacity to decrease (Andrade et al., 2017b; Assumpção et al., 2018).

FM treatment is shaped by a multidisciplinary approach, including pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapy (Collado-Mateo et al., 2017). Pharmacological therapy (antidepressants, opioids, sedatives and anti-epileptic drugs) is as effective as non-pharmacological therapy; however, it has greater side effects and less patient adherence (Izquierdo-Alventosa et al., 2020). Furthermore, non-pharmacological therapy, such as physical exercise, cognitive-behavioural therapy, therapeutic education, relaxation techniques and physiotherapeutic measures, promote a consistent and effective range of benefits for this condition (Collado-Mateo et al., 2017; Da Cunha-Ribeiro et al., 2018; Marín-Mejía et al., 2019).

Physical exercise has proven most efficient among non-pharmacological therapies due to its benefits (Villafaina et al., 2019); all the while, being one of the most promising and profitable solutions (Izquierdo-Alventosa et al., 2020). There is a large variety of physical exercise types; however, the most documented are: aquatic activities, aerobic exercise, flexibility programmes (Marín-Mejía et al., 2019), exergames (Collado-Mateo et al., 2017; Villafaina et al., 2019), yoga, Tai Chi, vibration training (Silva et al., 2019) and strength training (Andrade et al., 2017b; Bair & Krebs, 2020).

Aerobic exercise has been extensively researched and recommended for patients with FM due to the improvement it generates in physical capacity and functionality (Da Cunha-Ribeiro et al., 2018); and in turn, improves several symptoms such as pain, fatigue, sleep quality, depression and general health status (Andrade et al., 2017b).

Unlike aerobic exercise, little is known regarding the effective prescription of strength training, and literature remains limited (Da Cunha-Ribeiro et al., 2018). Based on a review by Busch et al. (2013) on strength training in women with FM, which found that the evidence published in that period was of poor quality due to factors such as incomplete description of exercise protocols, inadequate sample size and lack of information on adherence to training and incidence of adverse effects.

In light of the need to further develop evidence to improve the quality of care for people with FM, the following research question arises: what is the effect of strength training on aspects of muscle strength, well-being, symptoms, physical condition and adverse effects in people with FM? In order to describe the characteristics of muscle strength training programmes that assess well-being, symptoms, physical condition and adverse effects in people with FM as variable outcomes, this review of the literature was suggested. As secondary objectives, the adherence rate of participants to the programmes was estimated and the professions of the multidisciplinary team of researchers involved in the projects were identified.

Methodology

A search in Cochrane, Medline and Redalyc databases was conducted for experimental studies. The keywords for the search in English were fibromyalgia and strength training. Experimental studies published between 2016 and 2020 that evaluated the effect of the application of a physical training programme on some strength-related variable in people diagnosed with FM were included. No language restrictions were applied, articles published in English and Portuguese were included. Due to the interest in describing the types of training evaluated in research, a specific construct was assigned to delimit the type of training outcome related to strength. Were excluded: articles that did not describe the characteristics of the experimental training, programmes that did not include the performance of some form of physical exercise, and when access to the full text of the document was impossible. The search for articles was conducted during the month of December 2020.

A physical training programme was considered to include guidance for planned exercise over a period longer than four weeks, specifying the type of exercise, frequency, intensity and duration previously determined to be performed in individuals with FM diagnosis. Adherence rates to the training programmes were found in the authors’ report on the number of participants who started and finished per experimental group.

Due to the specification of the interest outcome of training programmes, a qualitative review of the information collected was carried out. One reviewer led the electronic search of databases in direct coordination with other reviewers; and an analysis on the relevance of the titles and abstract was jointly conducted. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through dialogue and consensus with two expert advisors. Data analysis was carried out using descriptive tables. The description identified the characteristics of the study population, experimental intervention, control group treatment, evaluation indicators, outcomes, conclusions, adherence to the intervention, adverse effect reporting, and project team collaborators –in accordance with the research methods and/or researchers’ statements–.

The level of evidence was assessed using a table adapted to identify grades of recommendation according to the GRADE system (The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) by Canfield & Dahm (2011). Lastly, the characteristics of the physical exercise training programmes were described regarding frequency, duration of sessions, total training time, intensity and other specifications. The criteria of the PRISMA statement were considered for the methodological design of the review (Page et al., 2021). Calculating the effect size was not possible due to the heterogeneity of the indicators used in the studies.

Results

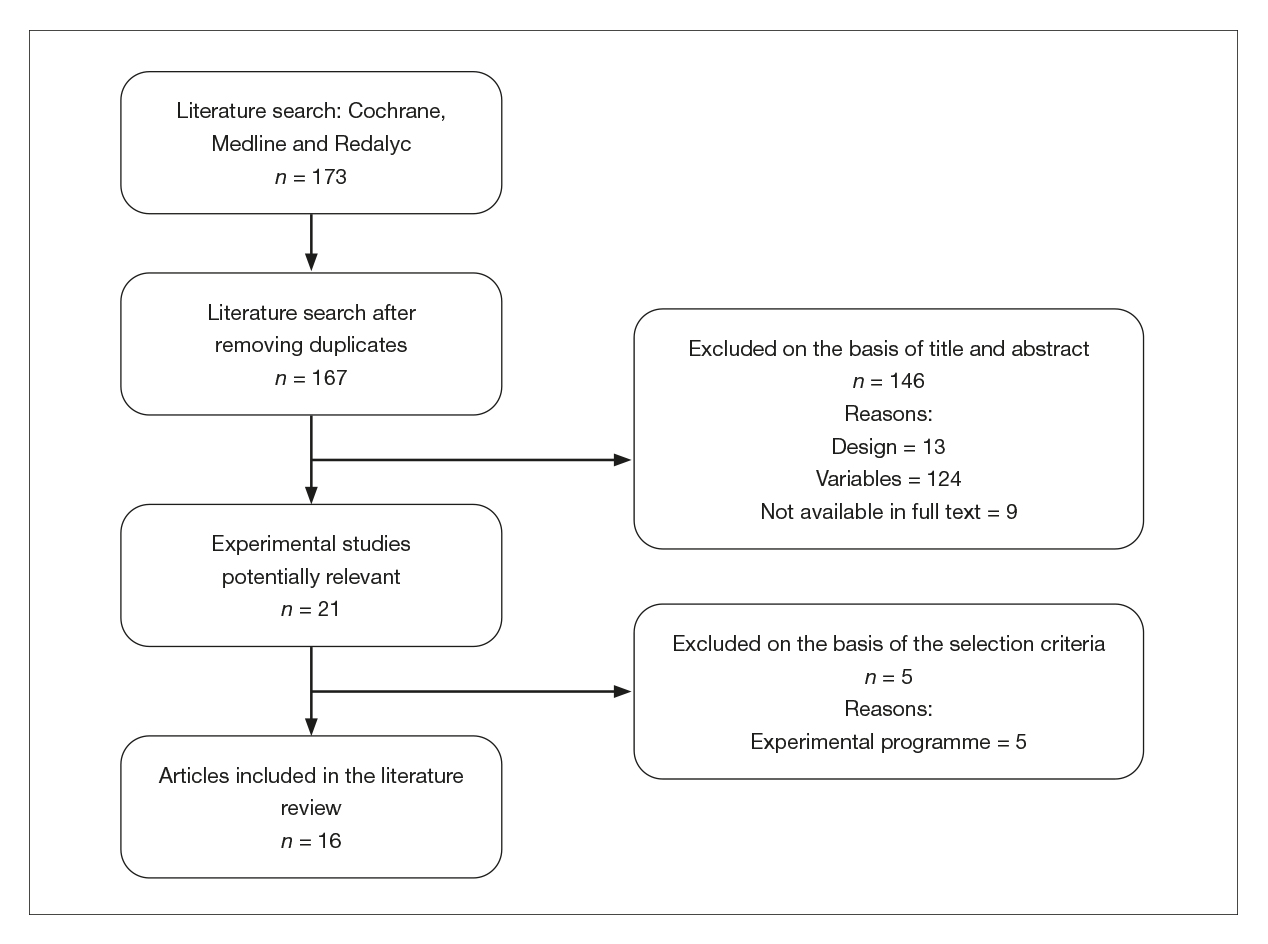

A total of 173 articles were identified in the three databases. The selection criteria were reviewed and the final decision was to process 16 articles (Figure 1).

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the participants by experimental group including age, country of origin and quality assessment. Moreover, the description of the evaluation indicators, the load and characteristics of the training programmes evaluated and the main results reported by the authors are presented.

Table 1

Description of participants by group, indicators and overall results of articles included in the review.

In nine of the articles, the control group was instructed not to exercise at all. However, in six studies related to the project by Larsson et al. (2015), an “active control” group was considered. Other authors applied cardiovascular training with isotonic strength stimuli and flexibility exercises (Marín-Mejía et al., 2019), muscle strength training (Silva et al., 2019), relaxation therapy, or the addition of intramuscular micro dialysis in the vastus lateralis part of the thigh (Ernberg et al., 2016) to the control group. The adherence rate for the experimental group was an average 82.76% (SD = 7.55, r = 73-97); the control group presented lower values, with 75.93% (SD = 11.83, r = 55-88). Four articles included the report of adverse effects such as pain (Da Cunha-Ribeiro et al., 2018; Ericsson et al., 2016; Ernberg et al., 2016; Palstam et al., 2016) in their findings. The multidisciplinary care team in the various studies included: neuroscience doctors, traditional medicine, physiology, physiatry, doctors specialised in sports and pain; specialists in human movement sciences, physical education professionals, kinesiology, dentistry, dance teachers and Tai Chi instructors.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the characteristics of training programmes aimed at people with FM in which well-being, symptoms, physical condition and adverse effects in people with FM were assessed as variables. Regarding the characteristics, studies were found in which physical activity is performed in less time according to the physical activity recommendations for adults aged 18 to 64 years, which establish 150 to 300 min of physical activity per week (WHO, 2020); however, those interventions consisting in 2 frequencies of 40 to 60 minutes had an effect on decreasing the intensity of the pain (Assumpção et al., 2018; Collado-Mateo et al., 2017; Da Cunha-Ribeiro et al., 2018; Kümpel et al, 2016; Silva et al., 2019), fatigue and improving the quality of sleep, anxiety and depression (Collado-Mateo et al., 2017; Kümpel et al., 2016). These results increase national CPG recommendations that physical activity is an approved non-pharmacological therapy for reducing chronic pain, improving physical functioning and quality of life in people with fibromyalgia, as well as reporting minimal negative effects (CENETEC, 2018). However, there still exist some differences in the total number of weeks necessary for the effects to show, especially residual effects, which have not been reported in the literature.

A 15-week, progressive, person-centred strength training programme based on self-efficacy principles has a positive effect on perceived recreational, social and occupational disability and, by improving sleep quality, impacts on physical fatigue in women with FM (Ericsson et al., 2016; Palstam et al., 2016). However, producing an anti-inflammatory effect on the vastus lateralis muscle is not sufficient neither at plasma level, nor does it affect pain nociception in FM patients (Ernberg et al., 2016; Jablochkova et al., 2019). This type of training produces greater results in lean individuals, as it can improve upper limb strength in obese or overweight individuals but has no impact on clinical symptoms or metabolic alterations. Adding a dietary intervention could help boost outcomes in FM patients who are overweight or obese (Bjersing et al., 2017; 2A quality).

Two Eastern disciplines have proven to be useful in reducing pain and in some aspects of physical condition (Kümpel et al., 2016; Wong et al., 2018). Applying the Pilates method twice a week helps reducing pain, improving functional capacity and sleep quality (2A quality). A 12-week Tai Chi training is helpful in decreasing pain and fatigue, as well as increasing strength and flexibility in women with FM (1A quality).

Other reports exist on the influence of strength training on sleep, psychological aspects related to depression and quality of life. Eight weeks of strength training may be safe and help reduce sleep disturbance in women with FM (Andrade et al., 2017b; 1B quality). Muscle stretching is known to improve quality of life in women with FM, while strength training decreases depression (Assumpção et al., 2018; 1B quality). An eight-week low-intensity strength training programme helps decrease pain, anxiety, depression, stress levels, while quality of life, and physical condition are improved in women with FM (Da Cunha-Ribeiro et al., 2018; 2A quality). There is evidence to suggest that strength training has the potential not only to decrease pain, but also to increase muscle strength (Izquierdo-Alventosa et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2019; 1A quality).

In addition, there are findings on the efficiency of online exergame-based interventions as they enable adherence to training, help reduce pain, improve physical condition and health-related quality of life (Collado-Mateo et al., 2017; Villafaina et al., 2019; 1B quality). In Colombia, a project has assessed the therapeutic effects of dancing; evidence suggests the positive impact of therapeutic dance in reducing the number of pain spots and symptoms associated with FM (Marín-Mejía et al., 2019; 2A quality).

It can be noted that regarding the scientific quality of the articles consulted, all 16 of them rate the quality of the effects of physical exercise programmes from moderate to high, including strength exercises in people with FM. Regarding the quality of evidence as assessed by the GRADE system, the studies included in this review contain three of the six levels identified by the system. The levels were: 1A. Strong Recommendation, high-quality evidence; 1B strong Recommendation, moderate-quality evidence; 2A weak Recommendation, high-quality evidence. As stated above, the published evidence is of moderate to high quality, which implies the possibility that progress has been made in relation to the concern of Busch et al., 2013, who previously reported this area of opportunity. Thus, the following can be established in people with FM from the state of the art:

The estimated adherence rate to the experimental trainings reviewed is above 73% in most publications, which should be considered for future projects. The causes for refusal were related rather to personal situations than to adverse events related to participation in the interventions. Three studies derived from the project by Larsson et al. (2015) reported the presence of localised thigh pain in participants; however, this effect was associated with an experimental procedure in addition to physical training (intramuscular micro dialysis of the vastus lateralis thigh). It is important that future interventions report adherence to the intervention and insist on follow-up assessments to explore whether a physical activity habit was generated in this portion of the population. Chronic pain is generally related to inability to perform physical activity, therefore, high rates of sedentary lifestyle (López-Mojares, 2019), refusal of the practice and non-adherence to exercise are usually found.

The multidisciplinary team involved in such research projects includes physiotherapists, doctors, dance teachers, physical education, physiology and sports professionals. The presence of pain associated with this pathology justifies the involvement of professionals from the clinical field in this type of project; however, given the advances in techniques and drugs for pain control, the involvement of professionals from other fields can be increasingly justified to help promote complete care for the re-adaptation to physical and social functionality of patients with FM in order to achieve conditions that enable them to be resilient to this pathology.

The main limitation of the analysed publications is that they only considered women in the study population. Although FM affects both sexes, the disease has been reported to be more prevalent in women with a ratio of nine to one (Katz et al., 2010; Silva et al., 2019), which implies that the knowledge generation has been developed primarily with women. The operational and technical difficulties involved in training mixed groups and/or the possibility of obtaining comparable study samples are limiting the study of the male population with FM. It has been reported that, although FM symptoms are similar in both men and women, women have a lower pain threshold than men, while sleep quality in men is the best indicator of pain sensitivity (Miró et al., 2012). This justifies adding indicators related to quality of life and sleep as complementary outcomes to pain management and physical condition in muscle strength training projects (Alves-Rodrigues et al., 2021; Solà-Serrabou et al., 2019).

With regard to the practical implication of this study, the information presented facilitates the literature review for evidence-based practice by physical activity and sport professionals in designing programmes focused on strength development for people with FM. In turn, it contributes to the reaffirmation of the benefit and safety this training modality can bring to patients with the disease. Based on this analysis, it is suggested that future experimental studies to evaluate training programmes in patients with FM should consider among its indicators the use of evaluations and parameters linked to the physical-functional and social capacity of the participants. However, physical training programmes need to be described considering each of their components (intensity, volume, frequency, duration and type of exercise). Also, it would be important to evaluate patterns in research for the dosage of the exercise based on stages or objectives according to the expectations of the participants (among others: pain control, physical-functional stability, social reintegration). Lastly, it would be necessary to report any injuries and/or adverse effects experienced by participants during the intervention programme.

Evidence-based practice is feasible with the information available until now. Among other things, the advancement of knowledge requires the involvement of a multidisciplinary team, the description of training load and quantity, the setting of goals regarding pain control, the promotion of physical-functional stability, or support for successful social reintegration.

Conclusions

In relation to the question of this project, regarding the effects of strength training on aspects of muscle strength, well-being, symptoms, physical condition and adverse effects in people with FM, the findings suggest the safety and beneficial aspect of this type of training to impact pain control, improvement of individual physical condition and functionality. Although the quality of the evidence is very good, there still exists a lack of reports on adverse events in this type of publication. The existence of a multidisciplinary team in this type of project is a constant in favour of the complete care required for FM patients. In fibromyalgia patients, physical activity must be systematically included in the therapeutic plan, optimising this prescription for maximum benefit.

References

[1] Alves-Rodrigues, J., Torres-Pereira, E., Zanúncio-Araujo, J., Ramos- Fonseca, J., Eliza-Patrocínio-de-Oliveira, C., López-Flores, M., & Costa-Moreira, O. (2021). Effect of Functional Strength Training on People with Spinal Cord Injury. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 144, 10-17. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2021/2).144.02

[2] Andrade, A., Torres Vilarino, G., de Liz, C. M., & de Azevedo-Klumb- Steffens, R. (2017a). Effectiveness of a strength training program for patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: feasibility study. ConScientiae Saúde, 16(2),169-176. https://doi.org/10.5585/conssaude.v16n2.7100

[3] Andrade, A., Vilarino, G. T., & Bevilacqua, G. G. (2017b). What Is the Effect of Strength Training on Pain and Sleep in Patients with Fibromyalgia? American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 96(12), 889–893. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000000782

[4] Assumpção, A., Matsutani, L. A., Yuan, S. L., Santo, A. S., Sauer, J., Mango, P., & Marques, A. P. (2018). Muscle stretching exercises and resistance training in fibromyalgia: which is better? A three-arm randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 54(5), 663–670. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.17.04876-6

[5] Bair, M. J., & Krebs, E. E. (2020). Fibromyalgia. Annals of Internal Medicine, 172(5), ITC33-ITC48. https://doi.org/10.7326/AITC202003030

[6] Bjersing, J. L., Larsson, A., Palstam, A., Ernberg, M., Bileviciute-Ljungar, I., Löfgren, M., Gerdle, B., Kosek, E., & Mannerkorpi, K. (2017). Benefits of resistance exercise in lean women with fibromyalgia: involvement of IGF-1 and leptin. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 18(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1477-5

[7] Busch, A. J., Webber, S. C., Richards, R. S., Bidonde, J., Schachter, C. L., Schafer, L. A., Danyliw, A., Sawant, A., Dal Bello-Haas, V., Rader, T., & Overend, T. J. (2013). Resistance exercise training for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013(12), CD010884. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010884

[8] Canfield, S. E., & Dahm, P. (2011). Rating the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations using GRADE. World Journal of Urology, 29(3), 311–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-011-0667-2

[9] Collado-Mateo, D., Dominguez-Muñoz, F. J., Adsuar, J. C., Garcia-Gordillo, M. A., & Gusi, N. (2017). Effects of Exergames on Quality of Life, Pain, and Disease Effect in Women with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 98(9), 1725–1731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.02.011

[10] Da Cunha-Ribeiro, R. P., Franco, T. C., Pinto, A. J., Pontes Filho, M., Domiciano, D. S., de Sá Pinto, A. L., Lima, F. R., Roschel, H., & Gualano, B. (2018). Prescribed Versus Preferred Intensity Resistance Exercise in Fibromyalgia Pain. Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 1097. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.01097

[11] Ericsson, A., Palstam, A., Larsson, A., Löfgren, M., Bileviciute-Ljungar, I., Bjersing, J., Gerdle, B., Kosek, E., & Mannerkorpi, K. (2016). Resistance exercise improves physical fatigue in women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 18, 176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-1073-3

[12] Ernberg, M., Christidis, N., Ghafouri, B., Bileviciute-Ljungar, I., Löfgren, M., Bjersing, J., Palstam, A., Larsson, A., Mannerkorpi, K., Gerdle, B., & Kosek, E. (2018). Plasma Cytokine Levels in Fibromyalgia and Their Response to 15 Weeks of Progressive Resistance Exercise or Relaxation Therapy. Mediators of Inflammation, 2018, 3985154. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3985154

[13] Ernberg, M., Christidis, N., Ghafouri, B., Bileviciute-Ljungar, I., Löfgren, M., Larsson, A., Palstam, A., Bjersing, J., Mannerkorpi, K., Kosek, E., & Gerdle, B. (2016). Effects of 15 weeks of resistance exercise on pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in the vastus lateralis muscle of patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 18(1), 137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-1041-y

[14] Izquierdo-Alventosa, R., Ingles, M., Cortés-Amador, S., Gimeno-Mallench, L., Chirivella-Garrido, J., Kropotov, J., & Serra-Añó, P. (2020). Low-Intensity Physical Exercise Improves Pain Catastrophizing and Other Psychological and Physical Aspects in Women with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103634

[15] Jablochkova, A., Bäckryd, E., Kosek, E., Mannerkorpi, K., Ernberg, M., Gerdle, B., & Ghafouri, B. (2019). Unaltered low nerve growth factor and high brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in plasma from patients with fibromyalgia after a 15-week progressive resistance exercise. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 51(10), 779–787. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2593

[16] Katz, J. D., Mamyrova, G., Guzhva, O., & Furmark, L. (2010). Gender bias in diagnosing fibromyalgia. Gender Medicine, 7, 19-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genm.2010.01.003

[17] Kümpel, C., Dias de Aguiar, S., Paixão Carvalho, J., Andrade Teles, D., & Pôrto, E. F. (2016). Benefício do Método Pilates em mulheres com fibromialgia. ConScientiae Saúde, 15(3),440-447. https://doi.org/10.5585/conssaude.v15n3.6515

[18] Larsson, A., Palstam, A., Löfgren, M., Ernberg, M., Bjersing, J., Bileviciute-Ljungar, I., Gerdle, B., Kosek, E., & Mannerkorpi, K. (2015). Resistance exercise improves muscle strength, health status and pain intensity in fibromyalgia - a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 17(1), 161. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-015-0679-1

[19] López-Mojares L.M. (2019). Esclerosis múltiple y ejercicio físico. En J. López-Chicharro & A. Fernández-Vaquero (eds.). Fisiología del ejercicio (pp. 948-955). Editorial médica Panamericana.

[20] Marín-Mejía, F., Colina-Gallo, E., & Duque-Vera, I. L. (2019). Danza terapéutica y ejercicio físico. Efecto sobre la fibromialgia. Hacia la Promoción de la Salud, 24(1), 17-27. https://dx.doi.org/10.17151/hpsal.2019.24.1.3

[21] Miró, E., Diener, F. N., Martínez, M. P., Sánchez, A. I., & Valenza, M. C. (2012). La fibromialgia en hombres y mujeres: comparación de los principales síntomas clínicos. Psicothema, 24(1), 10-15. reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/PST/article/view/9096

[22] Organización Mundial de la Salud. (2020). Physical activity. Fact Sheets. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity

[23] Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D. et al. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(160). https://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

[24] Palstam, A., Larsson, A., Löfgren, M., Ernberg, M., Bjersing, J., Bileviciute-Ljungar, I., Gerdle, B., Kosek, E., & Mannerkorpi, K. (2016). Decrease of fear avoidance beliefs following person-centered progressive resistance exercise contributes to reduced pain disability in women with fibromyalgia: secondary exploratory analyses from a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 18(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-1007-0

[25] Silva, H., Assunção Júnior, J. C., De Oliveira, F. S., Oliveira, J., Figueiredo-Dantas, G. A., Lins, C., & de Souza, M. C. (2019). Sophrology versus resistance training for treatment of women with fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 23(2), 382–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2018.02.005

[26] Solà-Serrabou, M., López, J. L., & Valero, O. (2019). Effectiveness of Training in the Elderly and its Impact on Health-related Quality of Life. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 137, 30-42. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2019/3).137.03

[27] Villafaina, S., Borrega-Mouquinho, Y., Fuentes-García, J. P., Collado-Mateo, D., & Gusi, N. (2019). Effect of Exergame Training and Detraining on Lower-Body Strength, Agility, and Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Women with Fibromyalgia: Single-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010161

[28] Wong, A., Figueroa, A., Sanchez-Gonzalez, M. A., Son, W. M., Chernykh, O., & Park, S. Y. (2018). Effectiveness of Tai Chi on Cardiac Autonomic Function and Symptomatology in Women with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 26(2), 214–221. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.2017-0038

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: October 1, 2021

Accepted: March 17, 2022

Published: July 1, 2022

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en