Investigative Teaching in Physical Education and Sports Teacher Training

*Corresponding author: Alfonzo-Marín Arnoldo aeam0002@red.ujaen.es

Cite this article

Alfonzo-Marín, A., Cachón-Zagalaz, J., Enríquez, L., & DelCastillo-Andrés, Ó. (2026). Investigative teaching in physical education and sport teacher training. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 163, 69-81. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2026/1).163.07

Abstract

The development of research skills in Physical Education (PE) and Sport (S) teachers is crucial for their professional development and for improving the educational process. This study, using a mixed approach and exploratory-descriptive design, aimed to diagnose the methods that teachers prioritize in the teaching of research within the training of PE and S teachers, as well as to evaluate the state of their research competencies. The ALCADE Research Competencies Form for teachers and structured interviews were used to analyze teachers’ perceptions and practices. The data, processed using IBM SPSS and ATLAS.ti, revealed that 50% of the teachers involved in research training programs mainly use traditional methodologies, with an excessive emphasis on lectures and master classes, which contributes to students’ passivity. These results highlight the urgency of contextualizing the teaching of research and adopting innovative methodologies in the training of Physical Education and Sport teachers, to create a more dynamic and effective didactic design.

Introduction

Physical Education and Sport (PE and S) in Higher Education has traditionally focused on the study of physical movement skills, curricular planning, recreation, health-oriented free movements, sport pedagogy, sport training methods and elite sport. However, other authors emphasize the importance of studying processes that ensure robust training in research skills to develop competent teachers (Villaverde-Caramés et al., 2021). In this sense, Blázquez (2013) argues that the competency-based approach conceives the teacher as a person trained for both the organization and practical implementation of the subject (González et al., 2021). To this end, it is essential to inculcate research skills in future teachers to scientifically support their teaching (Nápoles, 2013).

The training of research skills in pre-service PE and S teachers is crucial for their academic and professional development (Arcos et al., 2020). Educational research has shown that research competence not only enriches the teaching-learning process but also drives the advancement of knowledge in the field. It is essential for applying theoretical knowledge in practical contexts, emphasizing the need for robust training in epistemology and research methods for future professionals (Chiva-Bartoll et al., 2018; Rodríguez & Reyes, 2020). Likewise, the role of advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence, in research training has been highlighted for years, suggesting that their integration can significantly improve educational outcomes (Blasco & Pérez, 2007; Gavilanes et al., 2024).

Research training for future PE and S professionals depends not only on the acquisition of specific research knowledge but also on considering the political and institutional context of universities and their bureaucratic practices (Stylianou et al., 2017). Other findings highlight the importance of revisiting socio-critical research connected to transformative practice, considering open perspectives on inclusive education, and emphasizing technological changes, the use of lived histories, ethnography, and the experience provided by action research as a subjective and transcendental methodology (Felis-Anaya et al., 2017).

Action research is characterized as a highly reflective and participatory method of scientific research, ideal for the training of PE and S teachers (Keegan, 2016; Casey & Dyson, 2009). This approach is presented as a heuristic methodology that promotes a deep understanding of socio-educational realities and practices, and their transformation. It positions educational actors as key agents in solving problems within their environments, combining theory and practice. This allows teachers to identify problems in their educational context, implement strategic interventions, and systematically evaluate the results. Action research is based on a cyclical process of planning, action, observation, and reflection, which facilitates continuous feedback and the ongoing improvement of pedagogical practice (Colmenares & Piñero, 2008).

Action research combines research with practical action, enabling teachers to identify specific problems in their work environment, implement innovative solutions, and systematically evaluate the results (Ryan, 2020). This approach not only improves the quality of teaching but also fosters a reflective and critical attitude in teachers, encouraging them to question and continuously improve their pedagogical methods. In the field of PE and S, where practices and needs may vary widely across different contexts, the ability to adapt and improve evidence-based teaching strategies is particularly valuable (Baños et al., 2021). This methodology empowers prospective teachers to actively engage in the process of developing pedagogical knowledge, rather than being mere recipients of external theories (Cárdenas-Velasco, 2023). This collaborative and participatory approach strengthens the educational community, promoting the exchange of experiences and effective practices among colleagues (Fernández y Johnson, 2015). In addition, it fosters a culture of continuous learning and professional improvement that can lead to significant innovations in the teaching of PE and S. To excite students about the study of research, it is necessary to provoke them to analyze problems that seem impossible (Galdames-Calderón et al., 2024). It is essential to ensure that students participate, question, and discuss in groups (León, 1996).

In action research, future teachers assume the role of researcher-practitioners (de Parra et al., 2018), which promotes participatory research, a process in which the actors involved actively collaborate in the generation of knowledge. Action research involves not only solving immediate challenges but also critically reflecting on practices to improve educational processes and foster a culture of inquiry among teachers. Action research requires a cycle of action and reflection (Oestar & Marzo, 2022).

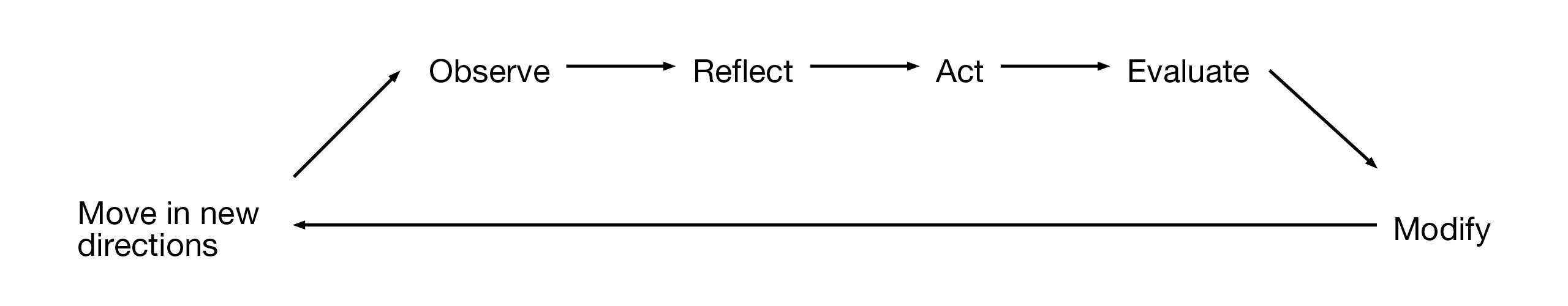

A diagram of the action-reflection cycle (McNiff, 2009), describes the cycle with the following steps:

Observe: identify something that needs attention or improvement; Reflect: analyze what is happening in the process or practice; Act: implement an action based on the reflection; Evaluate: assess the results obtained from the action; Modify: adjust practices based on the evaluation; Move in new directions: based on the modifications, move forward with new approaches or strategies.

This cycle is continuous because, when a point is reached where things seem to improve, the process generates new questions, leading to the start of the cycle all over again. Reflection during action, and even reflection on reflection itself, are the best tools for meaningful learning. This approach calls for deep questioning of the reflective process itself (McNiff, (2017). It is applied in educational contexts to improve practice reflectively and consistently.

In contrast, action research promotes a culture of active collaboration among prospective teachers, encouraging the exchange of insights and the implementation of effective strategies to optimize performance and increase motivation (López-Vargas & Basto-Torrado, 2010). This differs markedly from traditional research approaches, where students tend to adopt a passive role (Vaughan et al., 2019).

The traditional teaching methodology in PE and S teacher education presents several negative characteristics (Stringer, 2010), which can limit the effective development of future teachers. First, this approach tends to be highly passive, emphasizing the unidirectional transmission of knowledge, where students receive information without actively participating in its construction. This can lead to a lack of involvement and motivation on the part of students, who become passive recipients rather than active participants in their learning process.

Another negative characteristic is the rigidity of traditional methodologies, which tend to follow a pre-established and uniform format without adapting to the specific needs of students or the particularities of the educational context. This lack of flexibility prevents the personalization of learning and limits students’ ability to develop the critical and creative skills needed in their future teaching practice. Additionally, traditional methodologies tend to focus on the memorization of concepts and the repetition of content. This lack of dynamic interaction and practical application prevents future teachers from fully experiencing and understanding the research process in depth.

Traditional methodology often relies on the memorization of concepts (Shi & Yang, 2023), rather than fostering practical application and critical thinking. Finally, traditional methodology may not be sufficient to prepare future teachers for the constant evolution of research in the field of PE and S. Contemporary research requires an adaptive and flexible approach that traditional methodology cannot always provide. In this regard, a study found that 16 universities in Shanxi use the traditional teaching model as their principal approach in PE (Galván-Cardoso & Siado-Ramos, 2021). Consequently, it concluded that it is essential to implement alternative educational models that diversify and modernize teaching in this field (Li-ping, 2009; Martínez-Alonzo & Román-Santana, 2025).

In the current context, the predominant use of traditional methodologies in the teaching of research presents several significant weaknesses, especially considering that this subject requires a practical and active approach. This passive approach may limit students’ ability to experience and apply research methodologies in real contexts, which is crucial for the development of practical research skills. Another important weakness of traditional methodologies is the lack of contextualization of the examples provided by teachers. Often, the examples used in these methodologies do not relate to real or current situations in the field of PE and S. This disconnection between theory and practice makes it difficult for students to understand how to apply research principles in real scenarios. The main objective of this study was to diagnose the methods that teachers prioritize in the teaching of research within the training of PE and S teachers, as well as to evaluate the state of their research competencies.

Materials and Methods

The research was diagnostic-descriptive in nature. It was framed within a mixed (qualitative-quantitative) and cross-sectional approach. The ALCADE survey form, designed and validated by Marín et al. (2025), was applied. The survey was created using Google Forms 365 and distributed through various WhatsApp groups, where teachers of the relevant area were included. The validated questionnaire developed by Ríos Cabrera et al. (2023) was applied to measure research competencies in teachers (see Table 2). Additionally, a six-question structured interview was conducted to obtain a deeper understanding of participants’ perceptions and teaching practices (see Table 3).

A non-probabilistic purposive snowball sampling method was used. We began by identifying an initial group of research teachers in PE and S, who were invited to participate in the study through a Zoom link to the webinar: “Perspectives in teaching research for PE and S teacher education”. This link was distributed through WhatsApp groups. From this initial group, participants were asked to recommend other colleagues who also teach research in PE and S teacher education, resulting in a total of 28 participants.

Most surveyed professors were from Ecuador (60.7%), primarily aged 40–49 years (42.9%), with 11–20 years of experience (42.9%), and held a master’s degree (71.4%). This reflects an experienced and academically qualified group of teachers in the field of PE and S research.

To explore university professors’ perceptions of their pedagogical practices in teaching research within the context of PE and S, a qualitative methodological approach was applied using semi-structured interviews. A set of six open-ended questions was designed to elicit reflective responses regarding didactic planning, the integration of theory and practice, the use of information and communication technologies (ICT), the promotion of student creativity, the contextualization of content, and the incorporation of real-field data from professional practice.

The interview questions were: (1) What is your conception and didactic design of the classes you teach? (2) How is the theory-practice balance in your classes? (3) What value or importance do you give to the use of ICTs in your classes, and how frequently do you use them? (4) How do you motivate and promote student creativity in your classes? (5) How do you select and adapt examples in your classes to ensure they align with the principles of PE and S? (6) Do you collect and analyze real-field data related to PE and S?

The compiled responses were analyzed using ATLAS.ti software through a thematic coding strategy, that enabled the identification of emerging categories and interpretive patterns. In addition, a word-frequency analysis was carried out to determine the most recurrent concepts and their association with the defined dimensions. This qualitative methodology allowed for an in-depth understanding of teaching practices and revealed the degree of alignment between theory, practice, and applied research in the professional training of PE and S instructors.

Table 2

Operationalization of Research Competencies in Teachers (Taken From Cabrera et al., 2023)

In this table, the key dimensions of the research process are broken down into specific skills, each associated with a corresponding item (Ríos-Cabrera et al., 2023). In the dimension of “Posing the research problem,” skills such as detecting issues of interest and formulating the problem, which are essential for establishing the focus of the research (items 1-3), are highlighted. The dimension “Constructing the research framework” involves critical skills for evaluating the state of knowledge and building a solid theoretical framework (items 4-5). The dimension “Designing the method,” involves technical skills such as specifying the type of research, selecting samples, obtaining data, and incorporating information technologies, addressing both quantitative and qualitative methods (items 6-15). “Communicating research results” focuses on report writing and formulating conclusions, ensuring that results are presented clearly and coherently (items 16-20). Finally, the dimension “Verifying scientific rigor and coherence between components” addresses the critical evaluation of the internal coherence of the research, and the consideration of scientific rigor criteria, ensuring the validity and reliability of the study (items 9 and 18).

The operationalization of the questions made it possible to convert abstract pedagogical concepts into concrete and measurable variables. This process facilitated the objective measurement and analysis of teaching practices using clear categories that allow for a scientific interpretation of the data, ensuring coherence in the study.

Results

Survey Results

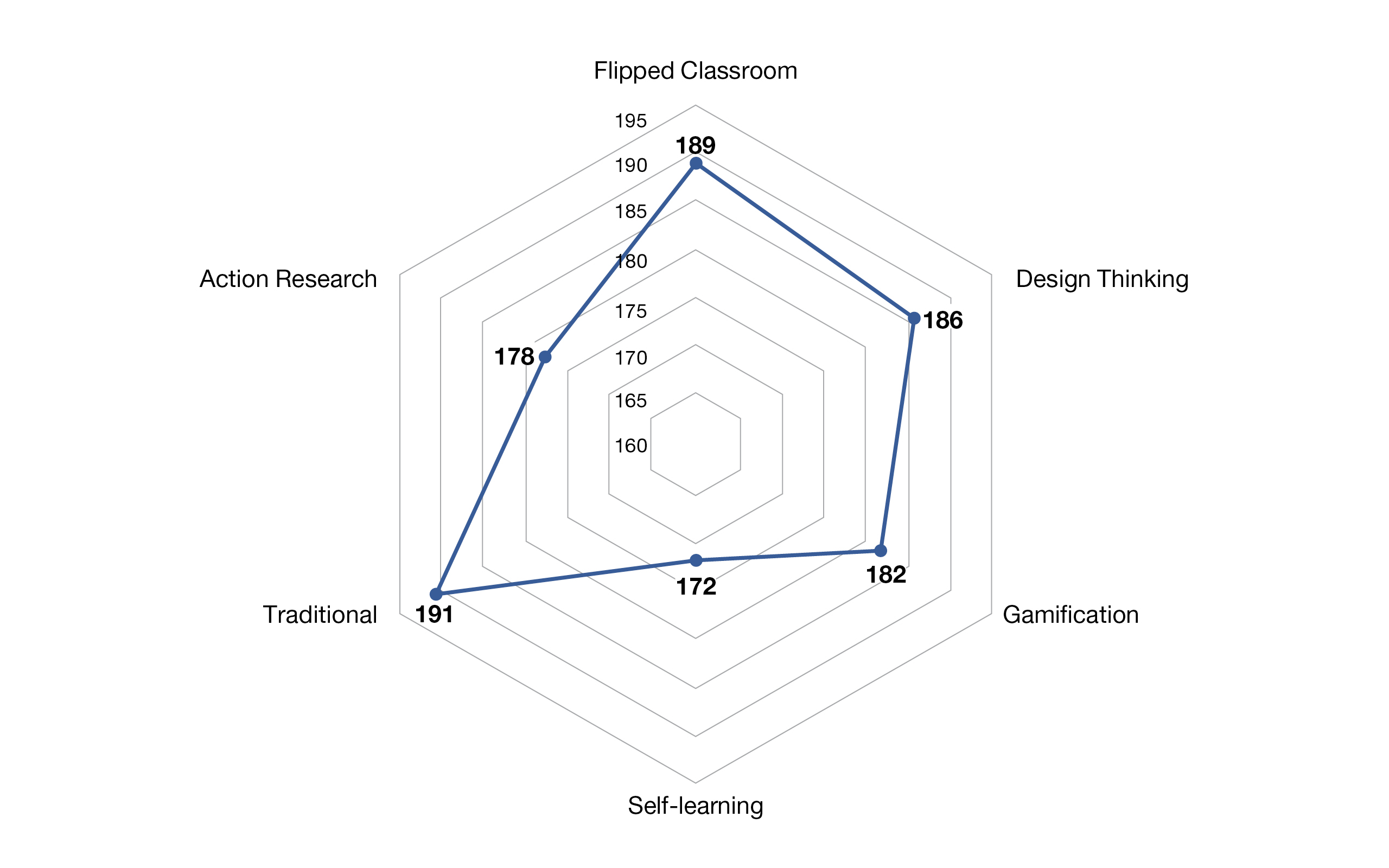

The range of 19 between the traditional method (191) and self-learning (172) reflects moderate variability in the frequency of use of these methods. The mean of 184.33 indicates that, overall, most teaching methods have a frequency above 180, suggesting a favorable trend toward their application. The median, with a value of 182.5, confirms that half of the methods exceed this frequency, reinforcing their consistent use. The mode, corresponding to the traditional method (191), highlights its popularity and preference over the others (see Figure 2). Finally, the standard deviation of 6.95 indicates moderate dispersion, implying minor differences in the application of the various methods.

The graph shows the distribution of frequencies by method. The distribution, from lowest to highest frequency, is as follows: Self-learning (172), Action Research (178), Gamification (182), Design Thinking (186), Flipped Classroom (189) and Traditional (191).

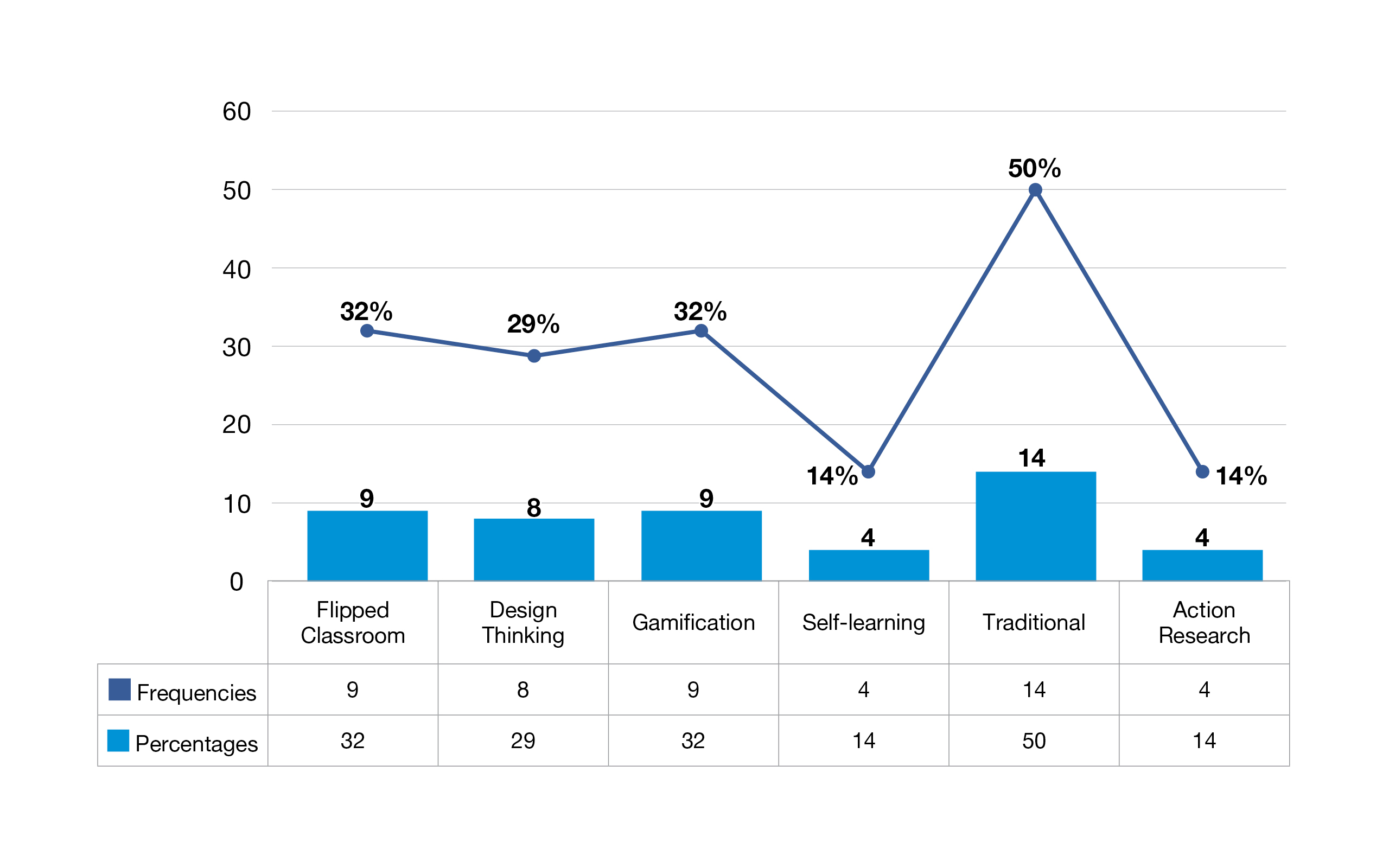

The graph shows the frequency and percentage of use of different teaching methods. Flipped Classroom and Gamification share the same frequency (9), which corresponds to 32% of use. Design Thinking has a slightly lower frequency (8), representing 29% usage. Self-Learning and Action Research have the lowest frequency (4), accounting for only 14% of use. Traditional Method stands out with the highest frequency (14), representing 50% of use.

Table 5

Questionnaire of Research Competencies in University Teachers (Validated by Cabrera et al., 2023)

The results obtained reflect a detailed evaluation of the teachers’ research skills, with means ranging from 3.36 to 4.39, indicating moderate to high mastery of the competencies assessed. The best-evaluated areas include qualitative data analysis, specifically the ability to analyze interview and text responses using qualitative methods (mean = 4.39, standard deviation = .951), suggesting high proficiency in interpreting non-numerical data. Conversely, the skill with the lowest score was the development of instruments for data collection (mean = 3.36, standard deviation = .951), revealing a potential gap in the creation and validation of methodological tools.

Regarding data dispersion, the standard deviation ranges from .634 to .951, indicating moderate variability among participants. Although some skills show a homogeneous domain, such as the formulation of the research problem (mean = 3.57, standard deviation = .790), other skills present a greater dispersion, suggesting significant differences in the level of competence of the teachers evaluated. These results underline the need to reinforce certain key competencies in future training programs, especially in instrument development and methodological research design.

The Pearson correlation table reflects a strong interrelation among the fundamental aspects of the research. All variables —including formulation of research problems, development of the referential framework, methodological design, communication of results, and scientific rigor— show high correlation coefficients, ranging from .804 to .921, indicating highly significant relationships between them. The statistical significance in all cases is .000, confirming that these correlations are not due to chance and are significant at the 99% confidence level.

The strongest correlations are observed between communication of results and scientific rigor (r = .921), and between the referential framework and communication of results (r = .908). This provides evidence that teachers who show a high level of scientific rigor and construct robust referential frameworks tend to communicate their research results more effectively. Overall, the consistency of the relationships among the variables suggests that good performance in one key area of research is directly associated with high performance in other areas, reinforcing the importance of a comprehensive approach to research training.

Interviews

The interview results reveal consistent patterns among university teachers regarding the design and delivery of research-oriented courses in Physical Education and Sport. Most participants reported structuring their classes with a strong emphasis on theoretical content, complemented by practical activities linked to the development of research projects—an approach they consider a balance between theory and practice—. As one teacher stated, “I maintain a 50/50 balance, where theory is immediately applied through practical exercises,” reflecting a perspective frequently shared among respondents. Similarly, the use of ICT was commonly valued as a key resource for accessing information and personalizing learning, with frequent use of tools such as Word, PowerPoint, and projectors. Regarding creativity, several teachers emphasized that it is encouraged by allowing students to identify and work on real problems within the context of Physical Education, as one participant noted: “I promote creativity by allowing students to express real issues in the context of physical education.” It was also commonly mentioned that examples and analytical situations are derived from students’ own experiences. However, a recurrent limitation identified was that the analysis of real-field data is not conducted during the course itself but is deferred to later stages under the guidance of academic advisors.

The analysis of the interviews reveals that the context of the EF and S, is the most prominent theme, with a total of 269 mentions and particularly high relevance in Interview 3 (29.77%). It is closely followed by the theoretical-practical balance, with 229 mentions (23.9% to 28.24% depending on the interview). Didactic design, accounted for 202 mentions (19.07% to 24.7%). The use of ICTs, with 197 mentions (10.36% to 31.49%), shows considerable variability among interviews, reaching its highest relevance in Interview 5. In contrast, the promotion of creativity, with 120 mentions (6.05% to 20.78%), was less frequently mentioned but remains a relevant theme.

The Word Frequency table of the interviews reflects the most recurrent words used during the interviews: The word “research” appeared 17 times. Other frequently mentioned words include “problem” (10 mentions) and “learning” (8 mentions), as well as “theory” (7 mentions) and “practice” (6 mentions). The terms “sport” and “physics” were each mentioned 4 times, while “project” appeared 5 times. Words such as “examples”, “virtual”, and “work” are associated with the use of technologies and practical approaches in the educational process, possibly reflecting the current context of digital or hybrid teaching. Words with 3 or fewer mentions, such as “scientific”, “theoretical”, and “knowledge”, were less prominent.

Discussion

The results of this study are in line with previous research highlighting the relevance of a sound theoretical framework and a clear definition of the research problem in teacher education (Chiva-Bartoll et al., 2018). A well-structured approach to methodological design and hypothesis formulation is crucial for the development of research competencies in the field of sports sciences (Rodríguez & Reyes, 2020). Properly posing research problems, constructing robust referential frameworks, selecting the correct methods, and effectively communicating research results with scientific rigor and coherence are key criteria for assessing research competencies in teachers and students (Marín et al., 2024), which coincides with the significant correlations observed between these variables in the study. Additionally, the integration of advanced technologies in research training is highly relevant, suggesting that such tools can enhance the teaching-learning process, an aspect that should be considered in future pedagogical proposals (Blasco & Pérez, 2007). Likewise, the strong correlation observed between the evaluation of results and scientific rigor confirms the findings of Stylianou et al. (2017), who emphasize that the research training of future professionals of PE and S depends not only on acquired competencies but also on the political and social context in which they are trained.

This research employed three key instruments that allowed for a comprehensive assessment of the research-teaching process in teacher education in PE and S. First, the ALCADE instrument was essential for capturing teachers’ perceptions of research-teaching methods, providing a robust quantitative framework for analysis. Second, the research competency questionnaire was used, which assessed teachers’ research competencies, providing detailed insight into their level of preparation and their ability to guide students in educational research. Finally, the structured interview allowed for the compilation of more in-depth qualitative data on teachers’ practices, facilitating the understanding of their perceptions and challenges in teaching research, and complementing the findings of the quantitative instruments.

The results obtained indicate the teaching methods most frequently prioritized by teachers in the instruction of research within PE and S teacher education. A significant tendency was observed toward the use of traditional methodologies, with a strong reliance on lectures and direct transmission of information. Figure 3 illustrates a clear preference for the traditional method, with a frequency of 50%, positioning it as the most commonly used among those evaluated, reflecting a conservative trend in teaching. The Flipped Classroom and Gamification methods each had a frequency of 32%, showing that they are popular, although not predominant, alternatives.

Design Thinking remains close with 29%, indicating moderate adoption. In contrast, the Self-Learning and Action Research methods, both with a frequency of 14%, evidence low implementation, suggesting that, according to the study sample, these more innovative approaches have not yet gained significant ground in inquiry-based teaching within PE and S teacher education.

Through correlational analysis, significant associations were identified between key aspects of research, such as problem formulation, methodological design, and the elaboration of the referential framework, suggesting a cohesive approach to research teaching and implying that teachers possess the necessary skills to be competent in research. The significant correlation between research competencies, research problem formulation, and scientific rigor (r = .804, p < .01) reflects an expected relationship according to the literature, where a clear and well-defined approach to problem formulation is a key indicator of rigor in research (Chiva-Bartoll et al., 2018). Furthermore, the strong correlation between the use of the referential framework and the quality of the results (r = .908, p < .01) underlines the importance of a well-constructed theoretical framework for the proper interpretation of findings. These results are aligned with previous studies that point out the need for a solid theoretical framework as a basis for research training in disciplines such as PE (Rodríguez & Reyes, 2020). The analysis of the interviews conducted with teachers revealed that the most outstanding dimensions were the theoretical-practical balance, didactic design and the use of ICTs —essential components in the teaching of research. These findings reinforce the need to combine these aspects of theoretical analysis with practice (Ryan, 2020) and to implement methodologies that empower future trainers in research practice (de Parra et al., 2018).

Limitations

One of the main limitations of the study is the sample size. With only 28 participating teachers, the findings may not be representative of the entire teaching population in the field of PE and S. However, due to the characteristics of the population, it is complex to recruit teachers with similar profiles to avoid selection bias. Finally, most of the innovative teaching methods, such as flipped classrooms, were not employed consistently, which precludes more detailed comparisons between traditional and innovative methods in terms of effectiveness in teaching inquiry skills.

The research by Cañadas et al. (2019), offers a valuable approach to Physical Education teachers’ perceptions of the development of their key competencies during their initial training, while also highlighting the existing differences related to their professional performance. Although the study presents a robust set of competencies as reported in the evaluation form, it is important to consider that the acquisition of research competencies is essential for strengthening and ensuring comprehensive professional practice. From a continuous improvement perspective, the ability to conduct research enables teachers to critically analyze their practice, adapt to changing contexts, and base their pedagogical decisions on evidence, thus effectively complementing the set of competencies evaluated in this study.

Ethical and Regulatory Compliance

This research was conducted in strict adherence to ethical principles and international standards on scientific integrity. The study followed the guidelines of the Code of Good Scientific Practices of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC, 2021), Throughout the process, the autonomy, dignity, and rights of all participants were respected, promoting responsible, inclusive, and equitable research practices.

Methodological and ethical rigor was maintained through procedures designed to ensure the transparency, validity, and reproducibility of the study. The development and application of data compilation instruments were guided by the Guide for Equal and Non-Sexist Use of Language and Images from the University of Jaén, ensuring inclusive communication and equitable gender representation in all research materials, (U.N., 2022).

Prior to data collection, individual orientation sessions were held with each participant, during which the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits were clearly explained. Written informed consent was obtained in compliance with ethical standards. All data were treated with strict confidentiality and anonymity and were used solely for academic and scientific purposes, in accordance with current data protection regulations and best practices in research ethics.

As part of our commitment to transparency and openness in science, the validation of the instrument used has been registered and documented on the Open Science Framework (OSF) platform, facilitating access for the scientific community and promoting the reproducibility of results. Retrieved from osf.io/vy7rt.

Conclusions

The study reveals a strong preference for traditional teaching methodologies in research instruction, characterized by a focus on direct content transmission and limited student engagement. This approach restricts the development of critical thinking and reduces students’ active involvement in the research process, which is essential for meaningful and reflective learning in Physical Education and Sport.

Despite teachers’ theoretical knowledge of research methods, a gap persists between theory and practical implementation, particularly in the construction of research instruments. This limitation can hinder their ability to effectively guide students through rigorous and contextually relevant research processes.

The analysis of research competencies highlights that a well-structured theoretical foundation enhances the interpretation of findings and the formulation of sound conclusions. This reinforces the importance of scientific rigor and methodological coherence throughout all stages of research-based teaching.

Ultimately, the integration of active methodologies, such as action research, emerges as a key strategy to promote autonomy, critical reflection, and adaptability to contemporary pedagogical and research challenges in the training of future Physical Education and Sport professionals.

References

[1] Arcos, H. G. A., Mediavilla, C. M. Á., & Espino, Y. G. (2020). Formación de habilidades investigativas en estudiantes de Cultura Física. Killkana sociales. Revista de Investigación Científica, 4(1), 43-48. doi.org/10.26871/killkana_social.v4i1.616

[2] Baños, R., Sánchez-Martín, M., Navarro-Mateu, F., & Granero-Gallegos, A. (2021). Educación Física Basada en la Evidencia: ventajas y limitaciones. Revista Interuniversitaria De Formación Del Profesorado. Continuación De La Antigua Revista De Escuelas Normales, 96(35.2). doi.org/10.47553/rifop.v97i35.2.88336

[3] Blasco Mira, J. E., & Pérez Turpin, J. A. (2007). Metodologías de investigación en las ciencias de la actividad física y el deporte: ampliando horizontes. Editorial Club Universitario (Alicante, Spain). Available at: rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/12270/1/blasco.pdf

[4] Blázquez, D. (2013). Diez competencias docentes para ser mejor profesor de Educación Física. INDE.

[5] Cañadas, L., Santos-Pastor, M. L., & Castejón, F. J. (2019). Physical Education Teachers’ Competencies and Assessment in Professional Practice. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 139, 33–41. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2020/1).139.05

[6] Cárdenas-Velasco, K. (2023). Funcionalidad de las competencias investigativas en la aplicación del Proyecto Integrador de Saberes con estudiantes de pregrado. Cátedra, 6(2), 143-168. doi.org/10.29166/catedra.v6i2.4517

[7] Casey, A. & Dyson, B. (2009). The implementation of models-based practice in physical education through action research. European Physical Education Review, 15(2), 175–199. doi.org/10.1177/1356336X09345222

[8] Chiva-Bartoll, Ó., Peris, C. C., & Piquer, M. P. (2018). Action-research on a service-learning program in teaching physical education. Revista de investigación educativa, 36(1), 277–293. Available at: revistas.um.es/rie/article/download/270581/221681

[9] Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC). (2021). CSIC Code of Good Scientific Practices. Available at: www.csic.es/sites/default/files/2023-01/cbpc_csic2021.pdf

[10] Colmenares, A. M., & Piñero, M. L. (2008). La investigación acción. Una herramienta metodológica heurística para la comprensión y transformación de realidades y prácticas socio-educativas. Laurus, 14(27), 96–114. Available at: www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=76111892006

[11] de Parra, L. L., Hernández-Durán, X., & Quintero-Romero, L. F. (2018). Enseñanza de la investigación en educación superior. Estado del arte (2010-2015). Revista latinoamericana de estudios educativos (Colombia), 14(1), 124-149. doi.org/10.17151/rlee.2018.14.1.8

[12] Felis-Anaya, M., Martos-Garcia, D. & Devís-Devís, J. (2017). Socio-critical research on teaching physical education and physical education teacher education: a systematic review. European Physical Education Review, 24(3), 314–329. doi.org/10.1177/1356336X17691215

[13] Fernández, M. & Johnson, D. (2015). Investigación-acción en formación de profesores: Desarrollo histórico, supuestos epistemológicos y diversidad metodológica. Psicoperspectivas, 14(3), 93-105. dx.doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol14-Issue3-fulltext-626

[14] Galdames-Calderón, M., Stavnskær Pedersen, A., & Rodriguez-Gomez, D. (2024). Systematic Review: Revisiting Challenge-Based Learning Teaching Practices in Higher Education. Education Sciences, 14(9), 1008. doi.org/10.3390/educsci14091008

[15] Galván-Cardoso, A. P., & Siado-Ramos, E. (2021). Educación Tradicional: Un modelo de enseñanza centrado en el estudiante. Cienciamatria, 7(12), 962-975. doi.org/10.35381/cm.v7i12.457

[16] Gavilanes Vásquez, P. G., Adum Ruiz, J. H., García Ruiz, G. S., & Ruíz Ortega, M. G. (2024). Impacto de la Inteligencia Artificial en la educación superior. Una mirada hacia el futuro. RECIAMUC, 8(2), 213-221. doi.org/10.26820/reciamuc/8.(2).abril.2024.213-221

[17] González, D. H., Arribas, J. C. M., & Pastor, V. M. L. (2021). Incidencia de la Formación Inicial y Permanente del Profesorado en la aplicación de la Evaluación Formativa y Compartida en Educación Física (Incidence of Pre-service and In-service Teacher Education in the application of Formative and Shared Assessment). Retos, 41, 533–543. doi.org/10.47197/retos.v0i41.86090

[18] Hernández, B. (2009). Los métodos de enseñanza en la Educación Física. EfDeportes.com, 14(132), 1-14. Obtention of www.efdeportes.com/efd132/los-metodos-de-ensenanza-en-la-educacion-fisica.htm

[19] Keegan, R. (2016). Action research as an agent for improving teaching and learning in physical education: a physical education teacher’s perspective. The Physical Educator, 73, 255–284. doi.org/10.18666/TPE-2016-V73-I2-6236

[20] León, O. G. (1996). Cómo entusiasmar a 100 estudiantes en la primera clase de metodología e introducir al mismo tiempo 22 conceptos fundamentales de la materia. Psicothema 8(1), 221-226. Available at: www.psicothema.com/pii?pii=18

[21] Li-ping, J. (2009). The analysis of physical education teaching environment in Shanxi universities. Journal of Changzhi University.

[22] López-Vargas, B. I., & Basto-Torrado, S. P. (2010). From Implicit Theories to Teaching as Reflective Practice. Educación y educadores, 13(2), 275-291. Available at: www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=83416998007

[23] Marín, A. A., Cachón, J., Enríquez, L., & Del castillo-Andrés, Ó. (2024). Research methodology in physical education and sport teacher education: systematic review. Retos 59, 803–810. doi.org/10.47197/retos.v59.107478

[24] Marín, A. E. A., Zagalaz, J. C., & Andrés, Ó. D. (2025). Encuesta sobre métodos de enseñanza de la investigación en la formación del profesorado en Educación Física y Deporte: validez y confiabilidad. Retos 62, 918-928. doi.org/10.47197/retos.v62.109701

[25] Martínez-Alonzo, J. M. y Román-Santana, W. M. (2025). Metodología de la investigación académica: enfoques cuantitativo y cualitativo. Guía práctica para investigadores noveles. (Versión 1, 1ª ed., p. 1-252) [Computer software]. Editorial Feijóo. doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16749563

[26] McNiff, J. (2017). Action research: All you need to know (1st ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd. uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/action-research/book249661

[27] McNiff, J. (2009). You and your action research project. Routledge. doi.org/10.4324/9780203871553

[28] Nápoles, P. (2013). Acciones para el desarrollo de habilidades investigativas en estudiantes de tercer año de la carrera cultura física y deporte. EFDeportes.com, 185. www.efdeportes.com/efd185/habilidades-investigativas-en-cultura-fisica.htm

[29] Oestar, J., & Marzo, C. (2022). Teachers as Researchers: Skills and Challenges in Action Research Making. International Journal of Theory and Application in Elementary and Secondary School Education, 4(2), 95-104. Available at: jurnal-fkip.ut.ac.id/index.php/ijtaese/article/view/1020

[30] Ríos-Cabrera, P., Ruíz-Bolívar, C., Paulos-Gomes, T. & León-Beretta, R. M. (2023). Desarrollo de una escala para medir competencias investigativas en docentes y estudiantes universitarios. Areté, 9(17), 147-169. doi.org/10.55560/arete.2023.17.9.7

[31] Rodríguez, A. & Reyes, C. (2020). Formación de profesores en educación física en la Micromisión Simón Rodríguez. Caso: Monagas-Anzoátegui. Trenzar. Revista de Educación Popular, Pedagogía Crítica e Investigación Militante (ISSN 2452-4301), 2(4), 105-126. Available at: revista.trenzar.cl/index.php/trenzar/article/view/63

[32] Ryan, T. G. (2020). Action Research Journaling as a Developmental Tool for Health and Physical Education Teachers. International Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 12(2), 279–295. Available at: ijci.globets.org/index.php/IJCI/article/view/409

[33] Shi, W., & Yang, L. A. (2023). A Study on the Enhancement Strategies of Physical Education Teaching in Colleges and Universities Based on the Kano Model. Applied Mathematics and Nonlinear Sciences, 9(1). doi.org/10.2478/amns-2024-1962

[34] Stringer, E. (2010). Action Research in Education. International Encyclopedia of Education. International Encyclopedia of Education, 311–319. doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.01531-1

[35] Stylianou, M., Enright, E., & Hogan, A. (2017). Learning to be researchers in physical education and sport pedagogy: the perspectives of doctoral students and early career researchers. Sport, Education and Society, 22(1), 122–139. doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2016.1244665

[36] United Nations. (n.d.). Gender equality and women’s empowerment – Sustainable Development. www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/

[37] Vaughan, M., Boerum, C. & Whitehead, L. (2019). Action Research in Doctoral Coursework: Perceptions of Independent Research Experiences. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 13(1):6. doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2019.130106

[38] Villaverde-Caramés, E. J., Fernández-Villarino, M. A., Toja, M. B., & González Valeiro, M. (2021). Revisión de la literatura sobre las características que definen a un buen docente de Educación Física: consideraciones desde la formación del profesorado (A literature review of the characteristics that define a good physical education teacher: considera). Retos, 41, 471–479. doi.org/10.47197/retos.v0i41.84421

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: April 7, 2025

Accepted: August 8, 2025

Published: January 1, 2026

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en