Body Dissatisfaction, Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Anthropometric Data in Female Gymnasts and Adolescents

*Corresponding author: Eva María Peláez-Barrios evapelaezbarrios@gmail.com

Cite this article

Peláez-Barrios, E.M., & Vernetta, M. (2022). Body Dissatisfaction, Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Anthropometric Data in Female Gymnasts and Adolescents. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 149, 12-21. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2022/3).149.02

Abstract

The aim was to analyse and compare body dissatisfaction, Mediterranean diet adherence (MDA) and anthropometric characteristics between acrobatic gymnasts and non-gymnasts. A sample of 151 adolescent girls (81 gymnasts and 70 non-gymnasts) aged between 10 and 19 years was selected. Body dissatisfaction was assessed through the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ), MDA was analysed through the Kidmed Test and anthropometric measurements enabled to calculate body mass index (BMI), waist-to-height ratio (WHR) and body fat percentage (BF%). The results indicated that gymnasts achieved significantly higher body satisfaction scores than non-gymnasts. In terms of MDA, 70.4% of gymnasts and 31.4% of non-gymnasts obtained optimal MDA. Gymnasts’ body dissatisfaction was related to MDA, BMI and the rest of anthropometric measurements (p < 0.01), unlike non-gymnasts, for which only Weight-BMI, Height-Weight, WC-BSQ, WC-BMI, WC-Weight and WC-Height were related. In conclusion, gymnasts have less body dissatisfaction, higher MDA and a healthier BMI than non-gymnasts. Data suggest promoting acrobatic gymnastics within Physical Education programmes, as an extracurricular or competitive activity due to its benefits for both variables.

Introduction

The relations between body dissatisfaction and MDA have been the subject of some studies in adolescents, indicating that the MDA they have is average and decreasing as they get older, and they have low percentages of body dissatisfaction (Peláez & Vernetta, 2019). The few studies that compare adolescents who practice AG and sedentary adolescents in relation to BI (Peláez et al., 2021) or MDA (Peláez and Vernetta, 2021) show that gymnasts have a better perception of their body image (BI) and better MDA than others, although results can vary depending on the sport (González-Neira et al., 2015; Rubio-Arias et al., 2015). Acrobatic gymnastics (AG) is an aesthetic sport of great technical complexity, in which BI, weight, a low body mass index (BMI) and a low fat percentage along with physical qualities are decisive in obtaining good results. Both socio-motor and aesthetic characteristics qualify it as a highly positive PAS within the context of physical education, and as an extracurricular activity in sport schools or clubs. Thus, practising physical activity on a regular basis has important physical condition and psychosocial benefits for adolescence, which is a time of great vulnerability for body image and where major physical and emotional changes occur. Moreover, the value placed on BI is increasing and particularly affects those involved in certain sports. This preoccupation impacts on eating habits and daily PAS, it can even reach obsession in the practice of sports and the strict control of diets (Valverde & Moreno, 2016). BI in adolescents is one of the most popular topics due to the importance that society gives to beauty and the industry being dedicated to physical appearance (Valles et al., 2020). This BI is the mental representation that each person has of their own body (Bonilla & Salcedo, 2021), which can be influenced by several factors related to lifestyle habits. When the perception of BI does not meet expectations, it is said that the person perceives their body according to their ideals and not according to reality, producing an alteration in it, such as body distortion or dissatisfaction.

In recent decades, having healthy lifestyle habits has become a great concern. Moreover, good nutrition and regular PAS practice have been proven essential for staying in good health and for the prevention of developing potential diseases (Kanstrup et al., 2020). In 2007, the European Commission on Public Health suggested that a balanced diet and sufficient regular physical activity are important factors in fostering and maintaining good health (Moral-García et al., 2021). The Mediterranean diet (MD) is one of the most renowned and studied dietary patterns in the world, considered a balanced diet, rich in fibre, antioxidants and unsaturated fats. It is characterised by a high consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables, whole grains, pulses, nuts, olive oil, moderate consumption of dairy and fish, and low consumption of red meat and deli meats (Serra-Majem et al., 2019). There is ample evidence of its benefits against several diseases and pathologies, as well as a protective role in cognitive impairment, dementia and depression (Dussaillant et al., 2016). This diet is highly recommended for the general population, as well as for athletes, since it can improve their performance (Rubio-Arias et al., 2015). However, in recent years, fewer people adopt this nutritional pattern and rather choose a diet which is high in energy, rich in saturated fat and low in micronutrients (Martini and Bes-Restrollo, 2020). Similarly, the number of adolescents who choose to not adhere to PAS practice is increasing, leading to a rising tendency towards unhealthy habits (Vernetta et al., 2018a). Therefore, it is important to reconcile the practice of PAS with an adequate diet in order to ensure better health. Furthermore, it appears that women who practise more PAS take better care of their diet than men (Castillo et al., 2007). However, there is contradictory evidence in this respect, since, female athletes are prone to have insufficient energy intake compared to normal population groups (Márquez, 2008) and, within female athletes, even more so among those competing in aesthetic sports such as gymnastics, where subjective assessment by judges often generates a preoccupation for weight and having a slim body (Esnaola, 2005).

In light of the above and the diversity of results, further studies are needed. The aim was to analyse and compare body dissatisfaction, MDA and anthropometric data between acrobatic gymnasts and non-gymnasts.

Methodology

Research design

Descriptive and observational study of quantitative methodology with a non-probabilistic, purposive sampling technique.

Participants

The sample consisted of 151 Andalusian female adolescents (81 acrobatic gymnasts and 70 who do not practise any sports). The age category was from 10 to 19 years (13.85±2.45). The selection criteria were: adolescent gymnasts practising acrobatics and adolescents not practising any sports, who did not present body image distortion disorders, and signed the informed consent in order to participate in the research. The study complied with the ethical principles for research involving human subjects established in the Declaration of Helsinki in 1975 and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Granada (no. 851/CEIH/2019).

Material and instruments

General data sheet. Questionnaire that allowed us to collect information related to age, school year and whether or not they practised any PAS in order to determine the sample of non-practising participants.

Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ). Questionnaire validated by Cooper et al. (1987), adapted to the Spanish population by Raich et al. (1996), which measures body dissatisfaction, comprised of 34 items with six response options (1=never and 6=always). Their score is sorted into four categories, ranging from no dissatisfaction (less than 81) to extreme dissatisfaction (more than 140). The reliability of the BSQ for this study with the McDonald’s Omega statistic was w=0.807, a value approved and reported by Ventura-León & Caycho-Rodríguez (2017).

Kidmed Test. To estimate the quality of nutritional habits, the MDA Kidmed test by Serra-Majem et al. (2004) was used. It consists of 16 questions with dichotomous answers (yes/no) depending on whether there was consumption or not. The score fits into three categories: <3=low AMD, 4-7= medium MDA and >8= optimal MDA.

Anthropometric measurements. Height, weight and waist circumference (WC) were assessed. Height was recorded using a SECA 220 stadiometer accurate to 1 mm and weight was recorded using a TEFAL digital scale accurate to .05 kg. BMI was determined using the Quetelet index (kg/m2). Being adolescents, the indicators suggested by Cole et al. (2007) were used: grade III thinness (<16); grade II thinness (16.1 to 17); grade I thinness (17.1 to 18.5); normal (18.5 to 24.9), overweight (25 to 30); and obesity (≥30). The WC was measured with a Seca 200 Type non-elastic tape (range from 0 to 150cm; accurate to 1mm). From which the waist-to-height ratio (WHR) was found to estimate the accumulation of fat in the core of the body. A ratio greater than or matching .55 would indicate a higher cardiometabolic risk (CMR) (Arnaiz et al., 2010). Regarding the subcutaneous triceps and subscapular skinfolds, a Holtain skinfold caliper was used, with a capacity of 50mm and accurate to 0.2mm. Which were used for the calculation of body fat percentage (BF%), performed using the specific references and equations of Slaughter et al. (1988).

Procedure

In order to explain the aim of the study and to ask for their collaboration, the gymnasts’ coaches and the principal of a secondary school in Andalusia (Spain) were contacted. When favourable responses were obtained, informed consent was required from the participants’ parents or legal guardians. Questionnaires were given to non-AG adolescent girls informing them about the tests. Then, anthropometric measurements were taken following the criteria of the International Society for the Development of Anthropometry specified in the international standards for anthropometric assessment (Marfell-Jones et al., 2012). The measurements for the gymnasts were taken during their training sessions, following these steps: completion of the BSQ, Kidmed and then the anthropometric measurements. One of the authors of this study was present at all times to answer any questions or doubts.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS, version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Quantitative variables were presented with the average and standard deviation and categorical variables in frequency and percentage. The normality and homoscedasticity of data were verified with the Kolmogorov Smirnov and Levene statistics, respectively. Since a normal distribution could not be observed, the use of a nonparametric analysis was chosen with the application of the Kruskal-Wallis, Mann-Whitney U test, and the association between variables through Spearman’s correlation coefficients. Statistical significance was established at p <.05.

Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive characteristics of the sample according to whether or not they practice AG.

Table 2 shows that 53% of the total sample was of normal weight, and this percentage was higher among gymnasts (56.8%) than non-gymnasts (48.6%). Furthermore, no gymnast was found at a grade III thinness level, nor at an overweight or obese level, although some non-gymnasts were found at these levels.

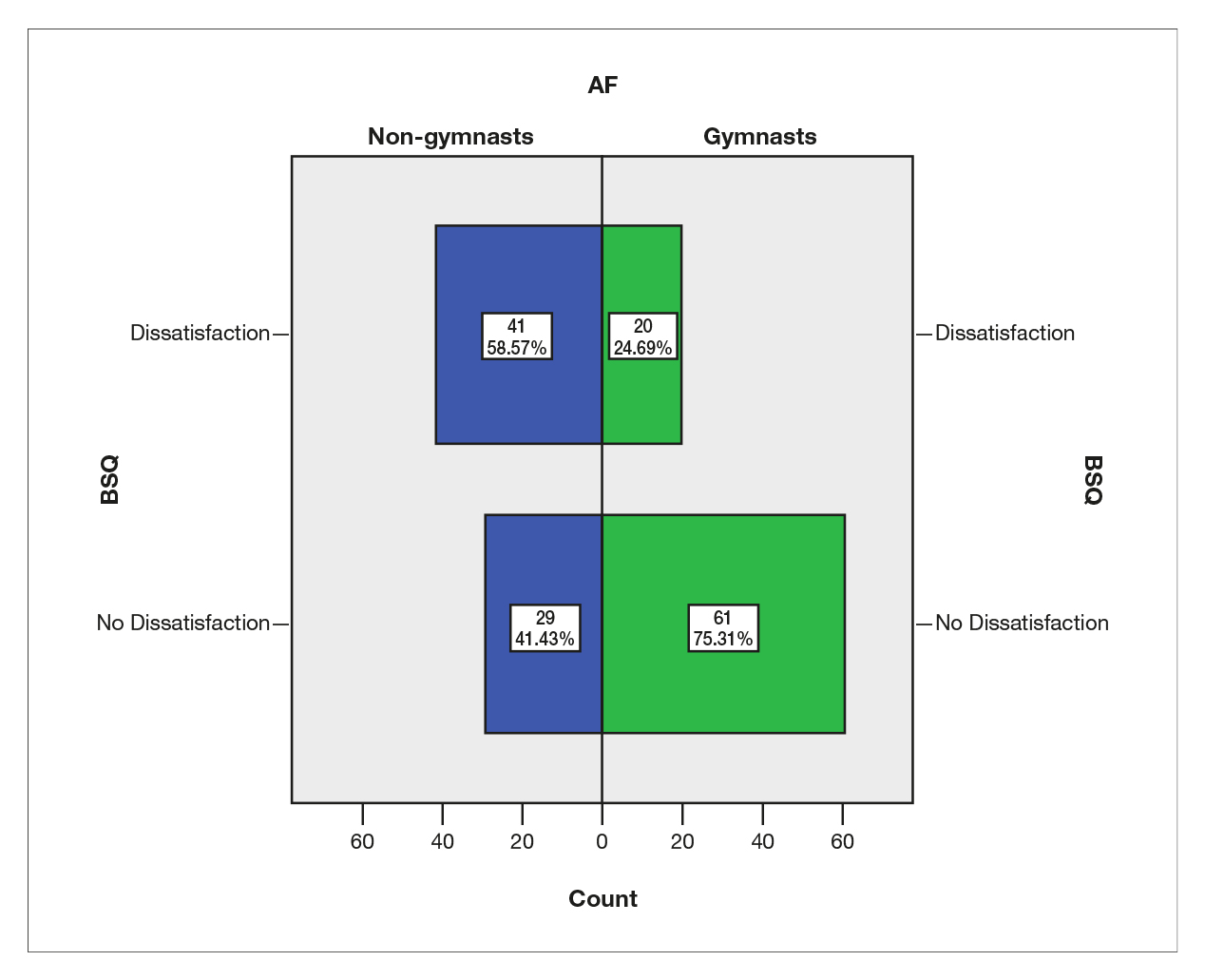

Table 3 shows that 75.3% of gymnasts and 41.4% of non-gymnasts presented no body dissatisfaction; gymnasts were the ones who obtained the best percentages in the different categories of the BSQ.

The Mann-Whitney U statistic showed statistically significant differences in the BSQ between gymnasts and non-gymnasts (U=1874.500, Z=-4.217, p =.000); average ranges were higher in the different categories of dissatisfaction among non-gymnasts than among gymnasts (see Figure 1).

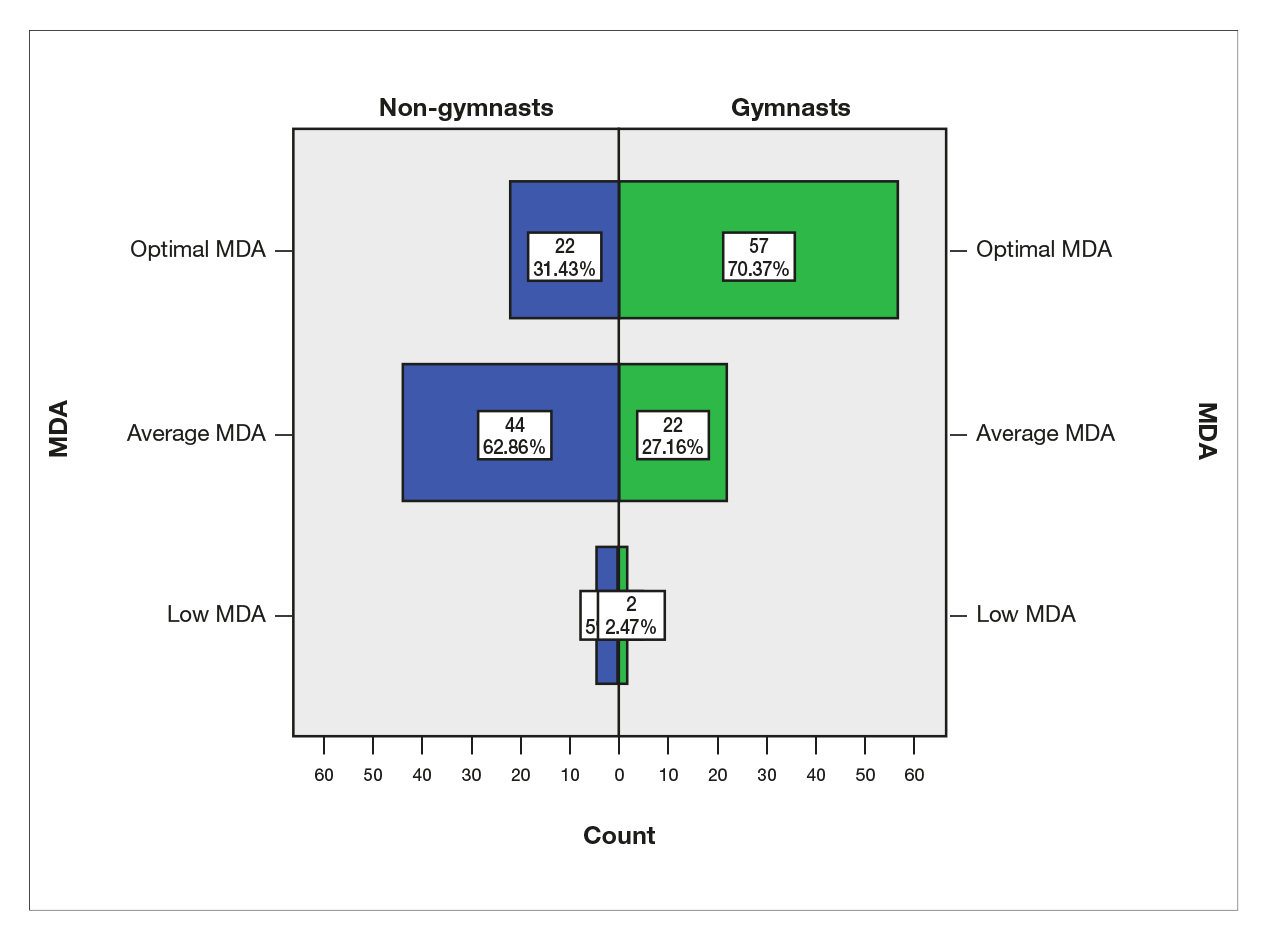

Regarding MDA results, 52.3% of the total sample presented optimal MDA, and these were higher among gymnasts than non-gymnasts (70.4%vs31.4%, respectively) (Table 4).

Similarly, the Mann-Whitney U statistic showed statistically significant differences in MDA depending on the practice of AG (U=1731.000, Z=-4.685, p =.000) (see Figure 2).

In table 5, the 16 items of the Kidmed were analysed according to whether or not AG was practised. Gymnasts were shown to have a high consumption of fruit, fresh vegetables, pulses and fish, while non-gymnasts had a high consumption of fast foods, industrial pastries, sweets and did not have breakfast, with significant differences between the two groups.

Lastly, table 6 shows positive correlations in gymnasts between MDA and BSQ, between BSQ and anthropometric measurements and between the different pairs of anthropometric variables. In non-gymnasts there was no relation between MDA-BSQ variables, although there were positive associations between BSQ and WC, as well as between different pairs of anthropometric variables with each other: Weight-BMI, Height-Weight, WC-BMI, WC-Weight and WC-height.

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to compare body dissatisfaction and nutritional aspects between acrobatic gymnasts and non-acrobatic gymnasts. Gymnasts were found to have lower body dissatisfaction, higher MDA, a higher number in normal weight and lower percentages of fat, thus confirming the hypothesis raised.

In terms of body dissatisfaction, gymnasts show less body dissatisfaction than non-gymnasts (40.40% vs. 19.21%), with significant differences. Our data contradicts scientific evidence originating from studies suggesting that this type of athlete is more likely to develop BI and eating disorders as they are preoccupied and even pressured to maintain a slim and aesthetic silhouette (Valles et al., 2020). More specifically, the study by Valles et al. (2020), comparing gymnasts with a control group, showed that elite gymnasts were the ones who reported a greater tendency to wish for a slimmer body, results that differ from the gymnasts in our study, who showed greater satisfaction with their BI than non-gymnasts, with significant differences. However, it is important to note that the study by Valles et al. (2020) does not specify the gymnastic discipline, and it can be interpreted that these higher percentages could be related to the discipline they practised. In fact, several studies comparing gymnasts from different disciplines confirm that rhythmic gymnasts tend to have more body dissatisfaction than artistic gymnasts, as well as lower body esteem than acrobatic gymnasts (Hernández-Alcántara et al., 2009; Vernetta et al., 2018b). Similarly, the study by Mockdece et al. (2016) in artistic gymnasts found significant concern for their BI. However, our results coincide with several studies that generally indicate good body satisfaction in gymnasts, as well as a positive perception of their BI (Ariza-Vargas et al., 2021). Specifically, our results confirm the recent study by Ariza-Vargas et al. (2021), which showed greater body satisfaction among acrobatic gymnasts compared to non-gymnasts.

In terms of MDA, the highest percentages in the optimal level stand out in gymnasts with 70.4% compared to 31.4% for non-gymnasts. Therefore, the percentages of low and medium MDA are higher in non-gymnasts, who need to improve their dietary pattern. Our percentage results in non-gymnasts are far from those reported in other studies carried out in Spanish adolescents from Granada and the southwest of Andalusia, where 53.6% and 73.33% obtained an optimal MDA (Chacón-Cuberos et al., 2018; Moral et al., 2019). However, they are more similar to the 45.2% of adolescent girls from Granada in the study conducted by Melguizo et al. (2021). This greater difference from MDA is due to a lower consumption of vegetables, fruit, fish, milk and pulses, also showing a higher intake of sweets, pastries and processed fast foods than gymnasts, with significant differences. When comparing our gymnasts with athletes from different disciplines, our optimal MDA data are better than the 51% among kayakers in Alacid et al. (2014), 47% of the swimmers in Philippou et al. (2017), 5.9% of female football players (González-Neira et al., 2015). As for female indoor football players, none recorded high MDA, their percentages were low and medium in MDA, 58.33% and 41.67%, respectively (Rubio-Arias et al., 2015). These results may be due to the importance given to the aesthetic component in this type of sport, which is not a common factor in other sports (Alacid et al., 2014; González-Neira et al., 2015). It is also important to note that our optimal MDA scores are higher than 52.2% among rhythmic gymnasts (Vernetta et al., 2018a). These differences in both sports can be seen in the different motor and morphological profiles of each speciality, as rhythmic gymnasts are characterised by an ectomorphic somatotype and acrobatic gymnasts by a mesomorphic-ectomorphic somatotype (Taboada-Iglesias et al., 2017; Vernetta et al., 2018b).

Analysing the results of the 16 items that make up the Kidmed test, gymnasts obtained the best results in the questions with positive connotations, with significant differences between both groups in all items, except “Do you eat fresh vegetables (salads) or cooked vegetables more than once a day”, “Do you eat pasta or rice almost daily (5 days or more a week)”, “Do you eat cereal or derivatives for breakfast”, “Do you eat nuts regularly (at least 2-3 times a week)”, “Do you use olive oil at home” and “Do you eat two yoghurts and/or 40 g of cheese every day”. These results are opposite in the questions with negative connotations, in which non-gymnasts obtain higher percentages. Similarly, several authors indicate that the adolescent practising sports part of the population shows healthier nutritional habits than those who do not practice any PAS (Peláez & Vernetta, 2021).

Concerning the anthropometric measurements, 56.8% of the gymnasts had a normal weight compared to 48.6% of non-gymnasts. It was among gymnasts that higher percentages in the level II of thinness were found, although there were none in level III of thinness; moreover, 11.4% of non-gymnasts were in the same level. No gymnast was found to be overweight or obese, and the non-gymnast group presented values of 11.4% and 1.4%, respectively. Statistically significant differences were shown between AG practice and BMI, data matching the study by San Mauro et al. (2016) in Spanish adolescent gymnasts, in which these relations are also established, and in the comparative study between Greek gymnasts and non-gymnast adolescents by Tournis et al. (2010), in which statistically significant differences are made between the practice of AG and BMI, such as with weight. In terms of WC and BF%, gymnasts have lower percentages than non-gymnasts, these results may be due to the importance that gymnasts give to both weight and BI as it is an aesthetic sport in which being thin and good looks are important factors in order to win and succeed (Vernetta et al., 2018b). More specifically, there are statistically significant differences in the BF% between both groups (19.52 gymnasts and 28.36 non-gymnasts), and these data are consistent with other studies in this group of the population such as that of San Mauro et al. (2016) & Tournis et al. (2010), in which the gymnasts’ BF% was substantially lower than non-gymnasts. Regarding the WHR variable, none of the groups presented CMR (0.38 gymnasts and 0.42 non-gymnasts), which is below the 0.52 suggested by Arnaiz et al. (2010) to be considered at risk.

Lastly, the results obtained from the correlational analysis emphasise the association of positive signs between the two main variables of the MDA -BSQ study in gymnasts, as well as between all pairs of anthropometric variables with each other, relations already reported in adolescents practising AG in all these pairs of anthropometric measurements (Vernetta et al., 2018b). Among non-gymnasts, only relationships between body dissatisfaction and WC exist (p < .001); results reported by Delgado-Floody et al. (2017), who found an association between body dissatisfaction and increased abdominal fat and excess weight. Similarly, our results in non-gymnast adolescent girls match the study by Estrada et al. (2018), who find no relation between both MDA-BSQ variables, although they advocate that higher MDA is important for health promotion.

The main limitations are: the small size of the sample, and the fact that it was made up only of females, which means that results cannot be generalised to the total population of adolescents, whether or not they practise AG, nor to males. Another limitation is the cross-sectional design, with which it cannot be concluded that the observed relations are causal. Therefore, in future research, the sample could be extended to males, as well as establish longitudinal studies and include other variables such as academic performance and even a comparison of samples of AG from different competitive levels.

Conclusions

The main findings show that gymnasts have lower body dissatisfaction, higher MDA and healthier BMI than non-gymnasts, and no gymnast was found to be overweight or obese. Furthermore, higher body satisfaction is related to better MDA and all anthropometric measurements in gymnasts. In non-gymnasts, there is only an association between BSQ and WC, several anthropometric measurements with each other, Weight-BMI, Height-Weight, WC-BMI, WC-Weight and WC-height.

The study shows that the practice of AG has a positive influence on the satisfaction variables with BI and MDA. These data suggest the need to develop specific programmes from Physical Education subjects to improve and increase the satisfaction of BI in non-gymnasts, suggesting didactic units related to gymnastic sports, as there is scientific evidence indicating that the practice of both AG and rhythmic gymnastics improves the perception of body image (Ariza et al., 2021; Vernetta et al., 2018b). Similarly, results highlight the need to offer parents and coaches guidance on healthy eating habits, ensuring they are aware that proper nutrition, and a healthy body composition, are key not only to maintaining health but also to optimising performance in sports.

References

[1] Alacid, F., Vaquero-Cristóbal, R., Sánchez-Pato, A., Muyor, Ma J., & López-Miñarro, P. Á. (2014). Adhesión a la dieta mediterránea y relación con los parámetros antropométricos de mujeres jóvenes kayakistas. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 29(1), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.3305/nh.2014.29.1.6995

[2] Ariza-Vargas, L., Salas-Morillas, A., López-Bedoya, J., & Vernetta- Santana, M. (2021). Percepción de la imagen corporpal en adolescentes practicantes y no practicantes de gimnasia acrobática. Retos, 39, 71–77. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v0i39.78282

[3] Arnaiz, P., Acevedo, M., Díaz, C., Bancalari, R., Barja, S., Aglony, M., Cavada, G., & García, H. (2010). Razón cintura estatura como predictor de riesgo cardiometabólico en niños. Revista Chilena de Cardiología., 29, 281–288. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-85602010000300001

[4] Bonilla, R. E. B., & Salcedo, N. Y. S. (2021). Autoimagen, Autoconcepto y Autoestima, Perspectivas Emocionales para el Contexto Escolar. Educación y Ciencia, 25. https://doi.org/10.19053/0120-7105.eyc.2021.25.e12759

[5] Castillo, I., Balaguer, I., & García-Merita, M. (2007). Efecto de la práctica de actividad física y de la participación deportiva sobre el estilo de vida saludable en la adolescencia en función del sexo. Rev Psicol Deporte, 16(2), 201–210. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=235119266001

[6] Chacón-Cuberos, R., Zurita-Ortega, F., Martínez-Martínez, A., Olmedo-Moreno, E. M., & Castro-Sánchez, M. (2018). Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Is Related to Healthy Habits, Learning Processes, and Academic Achievement in Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients, 10(1566). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111566

[7] Cole, T., Flegal, K., Nicholls, D., & Jackson, A. (2007). Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents. International Survey, 335, 194–197. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39238.399444.55

[8] Cooper, P. J., Taylor, M. J., Cooper, Z., & Fairbum, C. G. (1987). Then development and validation of the Body Shape Questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(4), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198707)6:43.0.CO;2-O

[9] Delgado-Floody, P., Martínez-Salazar, C., Caamaño-Navarrete, F., Jerez-Mayorga, D., Osorio-Poblete, A., García-Pinillos, F., & Latorre-Román, P.(2017). Insatisfacción con la imagen corporal y su relación con el estado nutricional, riesgo cardiometabólico y capacidad cardiorrespiratoria en niños pertenecientes a centros educativos públicos. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 34(5), 1044–1049. https://dx.doi.org/10.20960/nh.875

[10] Dussaillant, C., Echevarría, G., Urquiaga, I., Velasco, N., & Rigotti, A. (2016). Evidencia actual sobre los beneficios de la dieta mediterránea en salud. Revista Medica de Chile, 144(8), 1044–1052. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872016000800012

[11] Esnaola, I. (2005). Autoconcepto físico y satisfacción corporal en mujeres adolescentes según el tipo de deporte practicado. Apunts Educación Física y Deporte, 80 5–12. https://revista-apunts.com/autoconceptofisico-y-satisfaccion-corporal-en-mujeres-adolescentes-segun-el-tipodede-porte-practicado/

[12] Estrada, A.S., Velasco, C.N., Orozco-González, C.N., & Zúñiga-Torres, M. G. (2018). Asociación de calidad de dieta y obesidad. Pobl y Salud En Mesoaméric., 16(1). https://doi.org/10.15517/psm.v1i1.32285

[13] González-Neira, M., San Mauro-Martín, I., García-Aguado, B., Fajardo, D., & Garicano-Vilar, E. (2015). Valoración nutricional, evaluación de la composición corporal y su relación con el rendimiento deportivo en un equipo de fútbol femenino. Spanish Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 19(1), 36–48. https://dx.doi.org/10.14306/renhyd.19.1.109

[14] Hernández-Alcántara, A., Aréchiga-Viramontes, J., & Prado, C. (2009). Alteración de la imagen corporal en gimnastas. Archivos de Medicina del Deporte, XXVI(130), 84–92.

[15] Kanstrup, A. M., Bertelsen, P. S., & Knudsen, C. (2020). Changing Health Behavior with Social Technology? A Pilot Test of a Mobile App Designed for Social Support of Physical Activity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228383

[16] Marfell-Jones, M. J., Stewart, A. D., & De Ridder, J. H. (2012). International standards for anthropometric assessment. Wellington, New Zealand: International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry. http://hdl.handle.net/11072/1510

[17] Márquez, S. (2008). Trastornos alimentarios en el deporte: factores de riesgo, consecuencias sobre la salud, tratamiento y prevención. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 23(3), 183–190.

[18] Martini, D., & Bes-Restrollo, M. (2020). ¿La dieta mediterránea sigue siendo un patrón dietético común en el área mediterránea? Revista Internacional de la Alimentación y Nutrición, 71(4), 395–396.

[19] Melguizo, E., Zurita, F., Ubago, J.L., & González, G. (2021). Niveles de adherencia a la dieta mediterránea e inteligencia emocional en estudiantes del tercer ciclo de educación primaria de la provincia de Granada. Retos, 40, 264–271. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v1i40.82997

[20] Mockdece, C., Fernandes, J., Berbert, P., & Caputo, M. (2016). Body dissatisfaction and sociodemographic, anthropometric and maturational factors among artistic gymnastics athletes. Revista Brasileña Educación Física Esporte, 30(1), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-55092016000100061

[21] Moral, J. E., Agraso, A. D., Pérez, J. J., García, E., & Tárraga, P. (2019). Práctica de actividad física según la adherencia a la dieta mediterránea, el consumo de alcohol y la motivación en adolescentes. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 36(2), 420–427. https://dx.doi.org/10.20960/nh.2181.

[22] Moral-Garcia, J. E., Lopez-García, S., Urchaga, J. D., Maneiro R., & Guevara, R. M. (2021). Relationship Between Motivation, Sex, Age, Body Composition and Physical Activity in Schoolchildren. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 144, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2021/2).144.01

[23] Peláez, E. M., & Vernetta, M. (2019). Dieta mediterránea y aspectos actitudinales de la imagen corporal en adolescentes. Nutrición Clínica y Dietética Hospitalaria, 39(4), 146–154. https://doi.org/10.12873/3943pelaez

[24] Peláez, E. M., Salas, A., & Vernetta, M. (2021). Valoración de la imagen corporal mediante el body shape questionnaire en adolescentes: Revisión sistemática. In Dykinson (Ed.), Innovaciones metodológicas en TIC en educación (1a ed., pp. 2269–2293).

[25] Peláez-Barrios, E. M., & Vernetta Santana, M. (2021). Adherencia a la dieta mediterránea en niños y adolescentes deportistas: Revisión sistemática. Pensar En Movimiento. Revista de Ciencias del Ejercicio y la Salud, 19(1). Universidad de Costa Rica. https://doi.org/10.15517/pensarmov.v19i1.42850

[26] Philippou, E., Middleton, N., Pistos, C., Andreou, E., & Petrou, M. (2017). The impact of nutrition education on nutrition knowledge and adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in adolescent competitive swimmers. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 20(4), 328–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2016.08.023

[27] Raich, R. M., Mora, M., Soler, A., Ávila, C., Clos, I., & Zapater, L. (1996). Adaptación de un instrumento de evaluación de la insatisfacción corporal. Clínica y Salud, 1(7), 51–66. journals.copmadrid.org/clysa/art/ f2217062e9a397a1dca429e7d70bc6ca

[28] Rubio-Arias, J. Á., Ramos, D. J., Poyatos, Ruiloba, J. M., Carrasco, M., Alcaraz, P. E., & Jiménez, F. J. (2015). Adhesión a la dieta mediterránea y rendimiento deportivo en un grupo de mujeres deportistas de élite de fútbol sala. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 31(5), 2276–2282. https://doi.org/10.3305/nh.2015.31.5.8624

[29] San Mauro, I., Cevallos, V., Pina, D., & Garicano, E. (2016). Aspectos nutricionales, antropométricos y psicológicos en gimnasia rítmica. Nutrición Hospitalaria. Trabajo Original, 33(4), 865–871. https://dx.doi.org/10.20960/nh.383

[30] Serra-Majem, L., Ribas, L., Ngo, J., Ortega, R., García, A., Pérez-Rodrigo, C., & Aranceta, J. (2004). Food, youth and the Mediterranean diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutrition, 7(7), 931–935. https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2004556

[31] Serra-Majem, L., Román-Viñas, B., Sanchez-Villegas, A., Guasch- Ferré, M., Corella, D., y La Vecchia, C. (2019). Benefits of the Mediterranean diet: Epidemiological and molecular aspects. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 1–55.

[32] Slaughter, M., Lohman, T., Boileau, R., Hoswill, C., Stillman, R., Van Loan, M., & Bemden, D. (1988). Skinfold equations for estimation of body fatness in children and youth. Hum Biol, 60, 709–723.

[33] Taboada-Iglesias, Y., Vernetta, M., & Gutiérrez-Sánchez, Á. (2017). Anthropometric Profile in Different Event Categories of Acrobatic Gymnastics. Journal of Human Kinetics, 57, 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1515/hukin-2017-0058

[34] Tournis, S., Michopoulou, E., & Fatouros, I. G. (2010). Effect of rhythmic gymnastics on volumetric bone mineral density and bone geometry in premenarcheal female athletes and controls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 95, 2755–2762. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2009-2382

[35] Valles, G., Hernández, E., Baños, R., Moncada-Jiménez, J., & Rentería, I. (2020). Distorsión de la imagen corporal y trastornos alimentarios en adolescentes gimnastas respecto a un grupo control de adolescentes no gimnatas con un IMC similar. RETOS. Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 37, 297–302. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v37i37.67090

[36] Valverde, P., & Moreno, S. (2016). Percepción de la imagen corporal en mujeres jóvenes deportistas (Trabajo fin de grado). Universidad de Jaén, Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación.

[37] Ventura-León, J. L., & Caycho-Rodríguez, T. (2017). El coeficiente Omega: un método alternativo para la estimación de la confiabilidad. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 14(1), 625- 627. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=77349627039

[38] Vernetta, M., Montosa, I., & López-Bedoya, J. (2018a). Dieta Mediterránea en jóvenes practicantes de gimnasia rítmica. Revista Chilena de Nutrición, 45(1), 37–44. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/s0717-75182018000100037

[39] Vernetta, M., Montosa, I., & Peláez, E. (2018b). Estima coporal en gimnastas adolescentes de dos disciplinas coreográficas: gimnasia rítmica y gimnasia acrobática. Psychology, Society, & Education, 10(3), 301–314. https://doi.org/10.25115/psye.v10i3.2216

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: November 22, 2021

Accepted: March 28, 2022

Published: July 1, 2022

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en