Assessment of Hand-Eye-Laterality and Its Relationship With Technique in High-Level Tennis Players

*Corresponding author: Miquel Moreno miquel.moreno@uvic.cat

Cite this article

Moreno, M., Losilla, J. M., & Capdevila, Ll. (2026). Assessment of eye-hand laterality and its relationship with technique in high-level young tennis players. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 163, 58-68. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2026/1).163.06

Abstract

The hand-eye laterality profile (HELP) is a factor that may influence performance and technical fundamentals in tennis. This study aimed to: (a) assess the reliability of the hand-eye dominance test and the footwork preference test in tennis players; (b) analyze the distribution of the HELP profile in a sample of high-level tennis players; and (c) examine the relationship between the HELP profile and foot positions in different strokes involving movement. A sample of 173 tennis players (77 women and 96 men; mean age = 15.83 ± 2.86 years, range 11-23) was assessed. All of them were part of the Centro de Referencia program of the Catalan Tennis Federation, which brings together the most outstanding players in Catalonia, selected according to competitive performance and technical potential criteria. A standardized and validated method was applied to determine their HELP profile. The results confirmed that both the HELP test and the footwork preference test are reliable tools for assessment in tennis. In addition, 42.2% of the players showed a crossed profile (C-HELP), a proportion higher than in the general population. Specific patterns of foot position were also identified according to laterality profile, suggesting that the HELP profile influences stroke technique and tennis biomechanics. These findings support the relevance of hand-eye laterality in tennis and suggest that these tests are useful for tailoring training in high-level players.

Introduction

The hand-eye laterality profile (HELP) refers to the relationship between a person’s dominant hand and dominant eye and can be classified into two main types: a) crossed profile (C-HELP), when hand and eye laterality do not coincide; and b) homogeneous profile (UC-HELP), when hand and eye laterality coincide.

Recent research has shown growing interest in studying HELP in sport, revealing a higher prevalence of certain profiles in specific sports compared with the general population. For example, a higher proportion of the C-HELP profile has been observed in athletes than in non-athletes in sports such as golf, tennis, soccer, volleyball, handball, basketball, hockey, softball, and water polo (Moreno et al., 2022). In contrast, the UC-HELP profile appears advantageous in shooting sports, as it is more common than in the general population (Laborde et al., 2009; Razeghi et al., 2012).

Beyond the study of profile distribution, some authors have found relationships between HELP and motor performance. Castañer et al. (2018) identified an association between certain laterality profiles and the execution of complex movements in athletes, suggesting the influence of motor and ocular laterality on these movements. In addition, Díaz-Pereira et al. (2023) highlighted that lateral preference is related to motor creativity, a key factor in adapting to and learning sport skills. On the other hand, Balci et al. (2021) investigated whether HELP influenced visual reaction time in swimmers and concluded that no significant differences existed between profiles. However, they observed that the combination of the hand opposite to the dominant eye did significantly affect performance in visual reaction tasks. Evidence that certain hand-eye laterality patterns are associated with faster reaction times supports the relevance of investigating their role in perceptual performance in sport (Azémar, 2003; Dane & Erzurumluoglu, 2003).

In tennis specifically, it has been hypothesized that HELP may influence performance, making it a potentially relevant factor for training and talent identification (Moreno et al., 2022; Peters & Campagnaro, 1996). Previous studies have reported that 42% of the top 50 tennis players in the ATP rankings presented a C-HELP profile (Dallas et al., 2018), a figure significantly higher than the 10%–30% range observed in the general population (Robinson et al., 1997). Bache and Orellana (2014) also summarized the observations of Dorochenko (2013), who noted that most of the ATP top 10 had a C-HELP profile. Subhashree and Farzana (2025) concluded that tennis players with a C-HELP profile have greater serve accuracy. From a biomechanical and descriptive standpoint, Garipuy and Wolff (1999) reported that HELP profile may influence the characteristics of tennis strokes, such as body position and rotation during execution. According to these authors, players with a C-HELP profile tend to perform greater trunk rotation in forehand strokes, resulting in more neutral or semi-open foot positions. In contrast, players with a UC-HELP profile tend to hit the forehand from more open positions, requiring greater body rotation in backhand strokes.

Multiple studies have also underscored the importance of perceptual strategies for gathering and searching for information in tennis as trainable, performance-determining elements (Shim et al., 2005; Costa et al., 2023; Williams & Davids, 1998). Evidence further indicates that perceptual skills are related to stroke accuracy and overall motor timing (Özmen et al., 2020). In this context, our study may provide useful information on how HELP profile shapes perception and information processing during play, influencing stroke biomechanics through preferred patterns of footwork and body positioning.

However, some findings related to HELP should be interpreted with caution because of methodological limitations in previous research. In the studies by Bache and Orellana (2014) and Dorochenko (2013), the methods used to determine the prevalence of the C-HELP profile were not specified, whereas in the study by Dallas et al. (2018) ocular laterality was measured subjectively and without standardization. Moreover, many of the observed effects on performance are indirect, based on profile distribution, making it difficult to establish causal relationships (Moreno et al., 2022).

The present study sought to overcome these methodological limitations and determine the relationships between HELP and tennis technique in order to understand its impact on this sport. Specifically, the objectives were to: a) examine the validity and reliability of the hand-eye dominance test protocol proposed by Moreno et al. (2022) and of the footwork preference test, an original contribution based on an internal tool used by the Catalan Tennis Federation; b) determine the distribution of hand-eye laterality profiles (HELP) in a sample of high-level tennis players and identify whether there is a higher concentration of the crossed profile (C-HELP) compared with the general population using an objective, standardized, and validated HELP measurement method; and c) explore the relationship between HELP profile and technical aspects of tennis by analyzing how HELP influences the technical fundamentals of footwork and foot position in strokes performed after forward, backward, and lateral movements.

Method

Participants

This study involved the voluntary participation of 173 tennis players enrolled in the talent identification and monitoring program of the Catalan Tennis Federation, known as Centre de Referència. The sample comprised 77 women and 96 men (mean age = 15.83; SD = 2.86; range 11–23 years). This program, implemented at the High-Performance Center (CAR) in Sant Cugat del Vallès between 2019 and 2023, brought together the most outstanding players in Catalonia (Spain). Table 1 summarizes the main descriptive characteristics of the sample. The selection included all semifinalists in the Catalan championships for each age group and was complemented by other players chosen according to the technical criteria of the Catalan Tennis Federation talent selection team. Data were processed anonymously, and all participants, or their legal guardians in the case of minors, provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Ethics Committee for Human Experimentation of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (protocol code CEEAH-5745). The table with pseudo-anonymized data is available in CORA_RDR https://doi.org/10.34810/data2110).

Procedure

Assessment of hand-eye laterality profile (HELP)

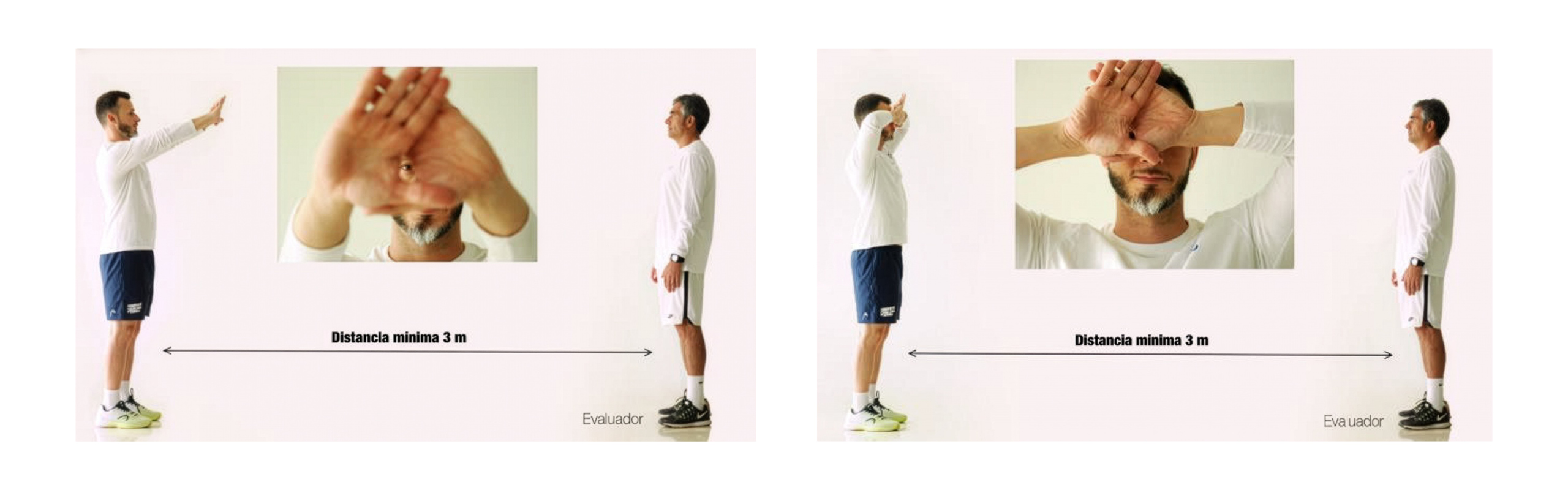

HELP profile was assessed in all study participants (n = 173). Dominant hand was determined by observing the gripping hand in the forehand stroke. Ocular dominance was determined using the active measurement protocol proposed by Laby and Kirschen (2011), considered the most comprehensive for assessing ocular dominance (Moreno et al., 2022). In this protocol, participants were asked to extend their arms forward at face height, with their hands together and palms facing forward, leaving a small opening between the thumbs and index fingers of both hands.

With both eyes open, they had to focus through this opening on the evaluator’s nose tip or camera lens, located 3 meters away. They were then instructed to bring their hands toward their face while keeping the target in focus at all times, so that the opening aligned with the dominant eye, thereby indicating ocular laterality (Knudson & Kluka, 1997). The test was performed three times, and the dominant eye was determined when the same eye was aligned in all three trials (Figure 1).

Finally, each player’s profile was classified according to whether hand laterality (direct observation) and eye laterality coincided (UC-HELP) or did not coincide (C-HELP).

Note. Reproduced with permission from the authors of the book Nuevas tendencias en el entrenamiento del tenis: modelo basado en la acción de juego, by Moreno and Baiget (2024).

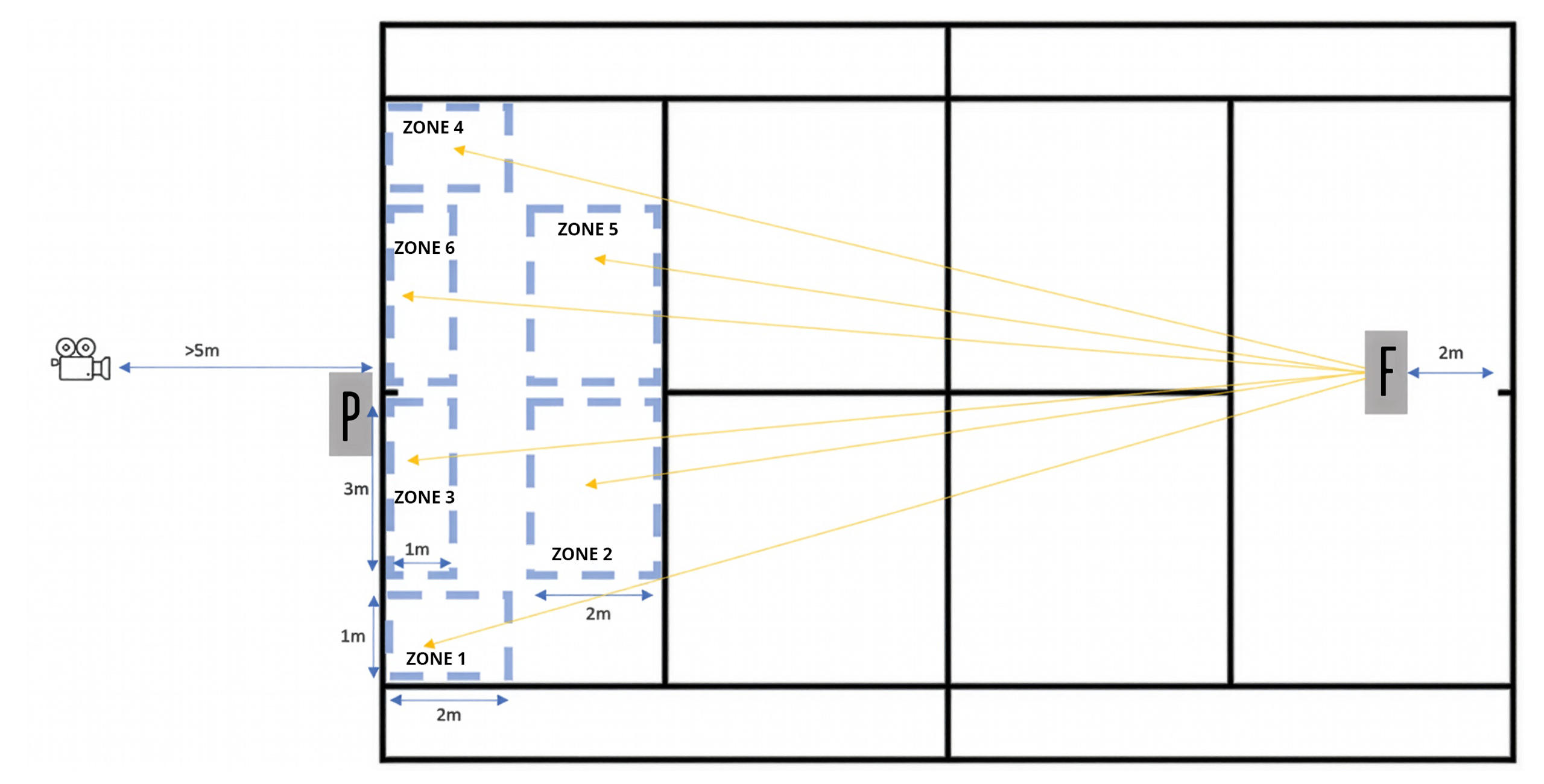

Protocol for Assessing Footwork Preference in Tennis

A purpose-designed test, routinely used by the Catalan Tennis Federation, was applied to assess footwork in a subsample of participants (n = 61). The protocol was video recorded and diagrammed, with zones and subzones detailed in Figure 2. Players started from the initial position (P), standing on the service line at the back of the court. A feeder, positioned 2 meters inside the baseline toward the net and aligned with the center of the court, hit the ball with the racket toward the corresponding zone. To standardize the test and ensure that players performed the intended movements, specific court zones were marked where the feeder’s ball had to bounce. When the ball did not bounce in the designated zone, the trial was repeated.

Note. P: player; F: feeder.

Regarding the general description of the protocol and execution conditions, players hit the ball ensuring that it landed within the boundaries of the opposite court while maintaining maximum realism in stroke execution. They were instructed to direct the ball cross-court or to the center of the court in strokes with lateral and backward movements (defense), and down the line in strokes with forward movements (attack), as these are the most logical directions according to game action (Moreno and Baiget, 2024). Each series included 3 repetitions, with the ball bouncing in the corresponding zone in each trial. All 3 trials were recorded to determine the predominant type of support. The protocol for assessing the technical fundamentals of the forehand and backhand strokes was as follows:

Lateral movement for forehand stroke. Lateral movement for forehand stroke. The feeder sent a ball that bounced in zone 1, requiring the player to move laterally 3 or 4 meters before executing a cross-court or central forehand (3 repetitions).

Forward movement for forehand stroke. The feeder sent a ball that bounced in zone 2, requiring the player to move forward 2 or 3 meters before hitting a down-the-line forehand (3 repetitions).

Backward movement for forehand stroke. The feeder sent a ball that bounced in zone 3, requiring the player to move backward 2 meters before executing a cross-court or central forehand (3 repetitions).

Lateral movement for backhand stroke. The feeder sent a ball that bounced in zone 4, requiring the player to move laterally 3 or 4 meters before executing a cross-court or central backhand (3 repetitions).

Forward movement for backhand stroke. The feeder sent a ball that bounced in zone 5, requiring the player to move forward 2 or 3 meters before hitting a down-the-line backhand (3 repetitions).

Backward movement for backhand stroke. The feeder sent a ball that bounced in zone 6, requiring the player to move backward 2 meters before executing a cross-court or central backhand (3 repetitions).

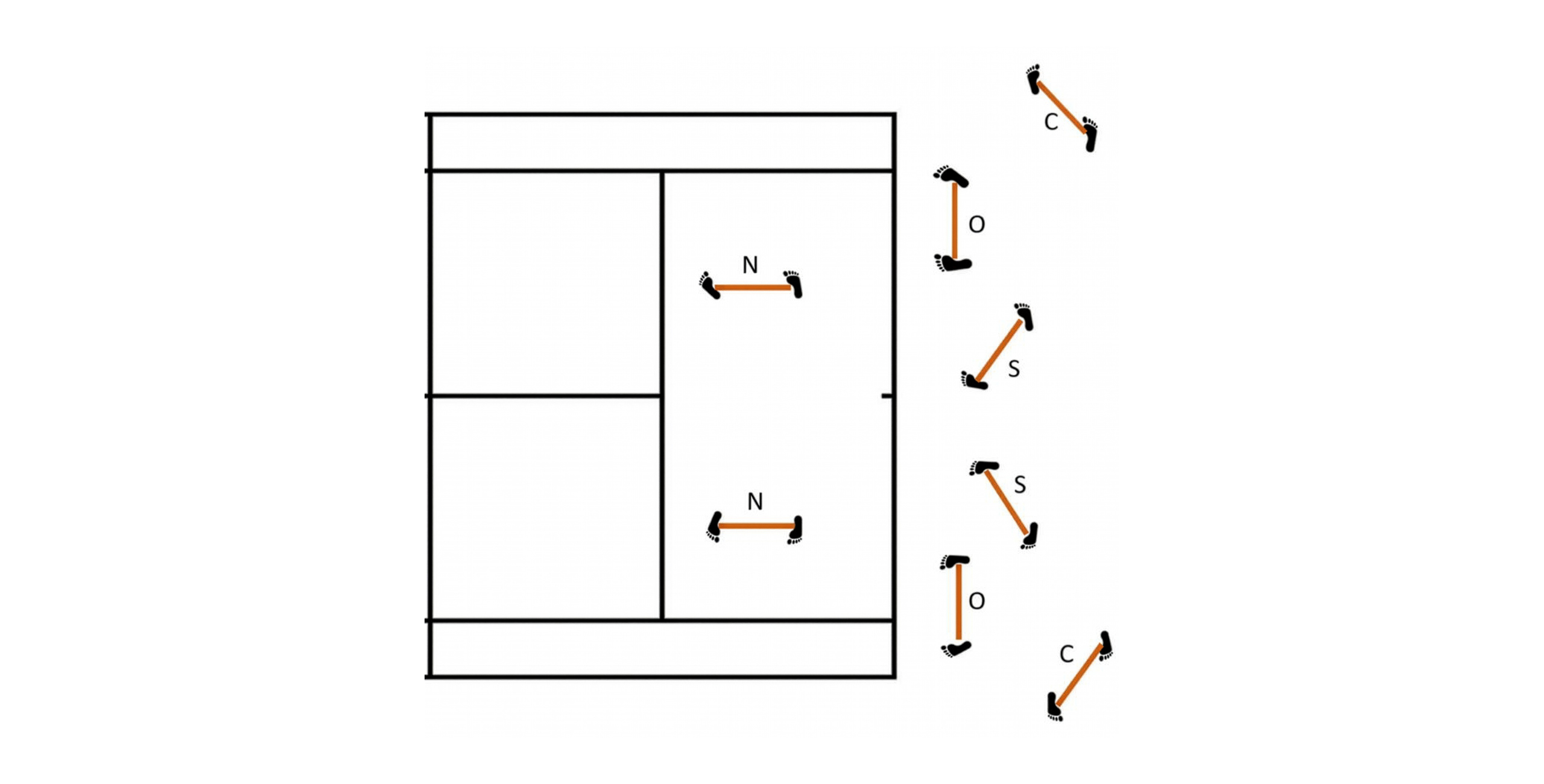

Regarding the description of the technical fundamentals of the type of support, for each ball hit to the designated zone, the type of support used by the player at impact was recorded. According to the categories established by Moreno and Baiget (2024), the technical fundamentals of the type of support (Figure 3) were as follows:

Open stance (O). At impact, the line of the hips was parallel to the net. The outside foot typically rotated externally.

Semi-open stance (S). At impact, the line of the hips was diagonal and turned away from the net. The front foot pointed toward the net, whereas the back foot was oriented laterally.

Neutral or side-on stance (N). At impact, the line of the hips was perpendicular to the net and the feet were parallel to it.

Closed stance (C). At impact, the line of the hips was diagonal and turned away from the net.

Note. N: neutral; O: open; S: semi-open; C: closed.

Reproduced with permission from the authors of the book Nuevas tendencias en el entrenamiento del tenis: modelo basado en la acción de juego, by Moreno and Baiget (2024).

Data Analysis

Cohen’s kappa statistic (Cohen, 1960) was calculated to analyze test-retest and inter-rater reliability for the test used to determine the hand-eye laterality profile (classified as C-HELP or UC-HELP) and for the footwork preference test in tennis players (classified as closed, neutral, open, or semi-open), following the interpretation criteria proposed by Landis and Koch (1977): poor (< .20), fair (.21-.40), moderate (.41-.60), substantial (.61-.80), and almost perfect (.81-1.0).

For each of the six strokes with movement assessed (forehand lateral, forward, and backward; and backhand lateral, forward, and backward), the X² statistic (Pearson, 1900) was calculated to analyze the statistical significance of differences in the distributions of the four types of support between players classified with C-HELP and UC-HELP hand-eye laterality profiles.

Results

Study of the Reliability of the Hand-Eye Dominance Test

First, test-retest reliability of the hand-eye dominance test was analyzed to determine the hand-eye laterality profile in a subsample of tennis players (n = 97), one month after the initial test. Second, inter-rater reliability was analyzed in another subsample of players (n = 69). Both analyses showed high reliability, with 94.8% agreement (Kappa = .892; 95% CI: .799, .986; p < .001) in the test-retest analysis and 100% agreement between raters (Kappa = 1; p < .001) (Table 2).

Table 2

Preferred foot positions based on stroke, type of movement, and hand-eye laterality profile

Study of the Reliability of the Footwork Preference Test in Tennis

To analyze the reliability of the footwork preference test, an instrument used by the Catalan Tennis Federation, a retest was conducted by having a second rater review the video recordings, following the same procedure as the first rater. For forward forehand supports, perfect agreement of 100% was obtained (Kappa = 1; p < .001). For lateral forehand supports, agreement was 98.4% (Kappa = .946; 95 % CI: .839, 1; p < .001). For backward forehand supports, agreement was 98.4% (Kappa = .941; 95% CI: .819, 1; p < .001). For forward backhand supports, agreement was 91.8% (Kappa = .826; 95% CI: .691, .973; p < .001). For lateral backhand supports, agreement was 100% (Kappa = 1; p < .001). Finally, agreement for backward backhand supports was 91.7% (Kappa = .826; 95% CI: .676, .981; p < .001).

Distribution of HELP Profiles

Based on the hand-eye dominance test, the distribution of laterality profiles was analyzed in the total sample of high-level tennis players (n = 173). Overall, 42.2% of participants were classified as C-HELP (73 players) and 57.8% as UC-HELP (100 players) (Table 2).

Preferred Foot Position Based on Hand-Eye Laterality Profile

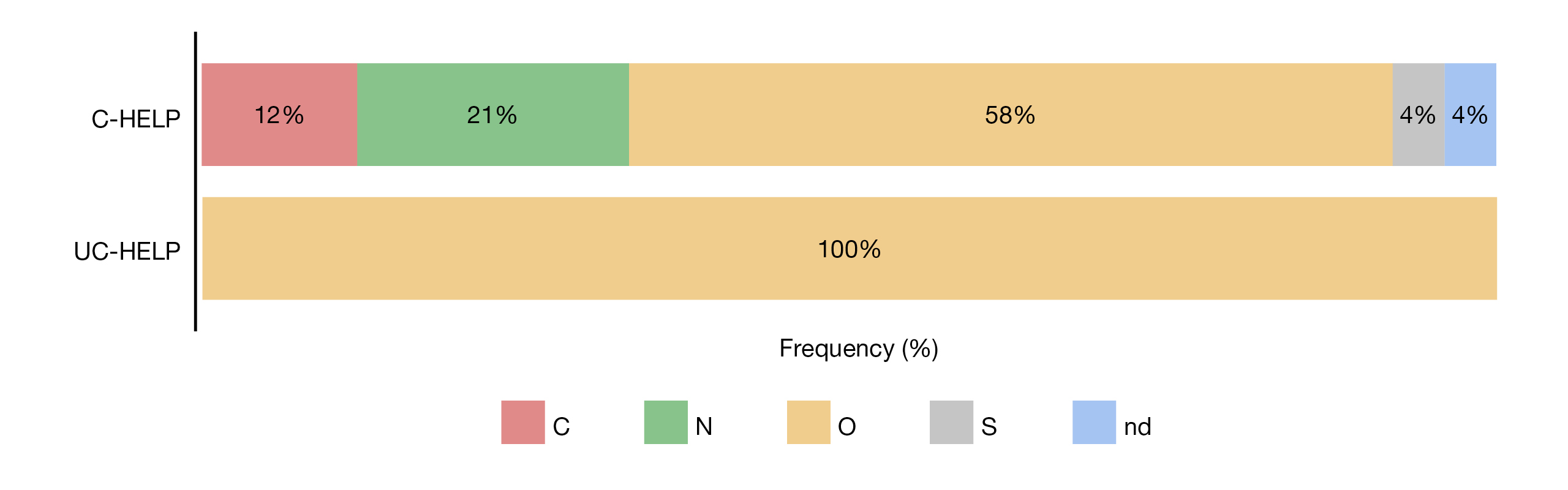

Forehand stroke with lateral movement

In forehand strokes with lateral movement, UC-HELP players showed a clear preference for the open stance (O): they adopted it in 100% of cases. In contrast, C-HELP players displayed greater variability in their positions, although the open stance (O) was still the most common, at 58.3%. The data also revealed that 4.2% of C-HELP players adopted an undefined position, varying their support across trials (Figure 4). These differences in the distributions of positions adopted by C-HELP and UC-HELP players were statistically significant (Table 2).

Note. C-HELP: crossed hand-eye laterality profile; UC-HELP: homogeneous hand-eye laterality profile; C: closed foot position;

N: neutral foot position; O: open foot position; S: semi-open foot position; ud: undefined foot position.

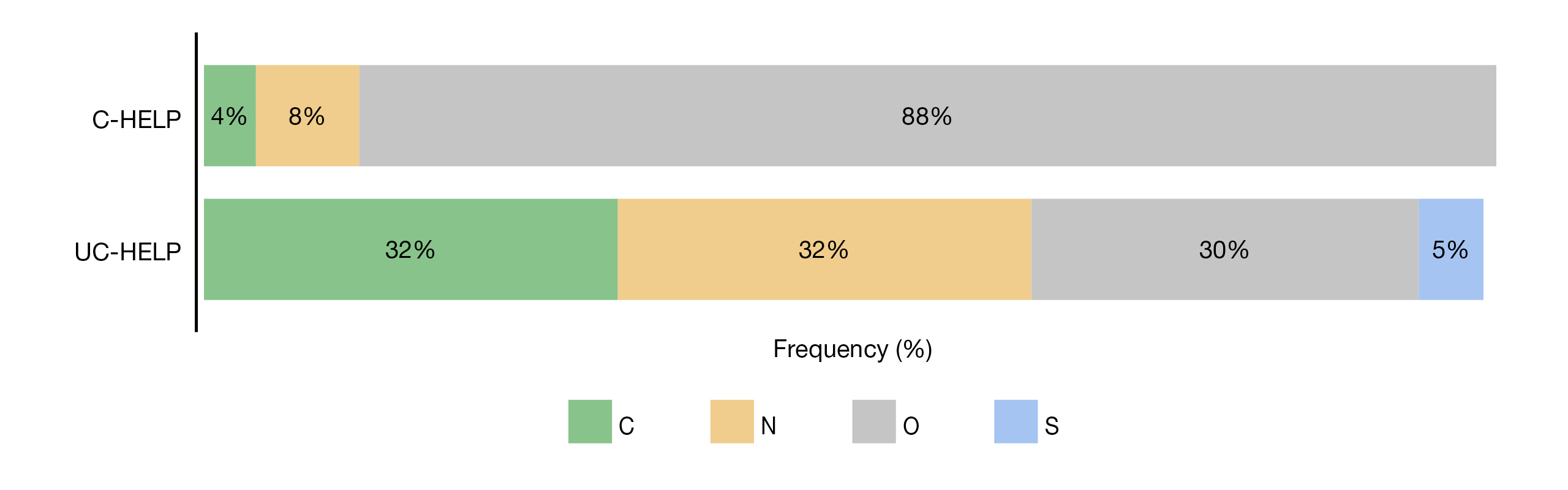

Backhand stroke with lateral movement

For backhand strokes with lateral movement, C-HELP players also showed a clear preference for the open stance (O), adopting it in 87.5% of cases (Figure 5), compared with only 29.7% of UC-HELP players. UC-HELP players displayed greater variability in their positions, with the neutral (N) and closed (C) stances being the most frequent, each accounting for 32.4% (Figure 5). These differences in the distributions of positions adopted by C-HELP and UC-HELP players were statistically significant (Table 2).

Note. C-HELP: crossed hand-eye laterality profile; UC-HELP: homogeneous hand-eye laterality profile; C: closed foot position; N: neutral foot position; O: open foot position; S: semi-open foot position.

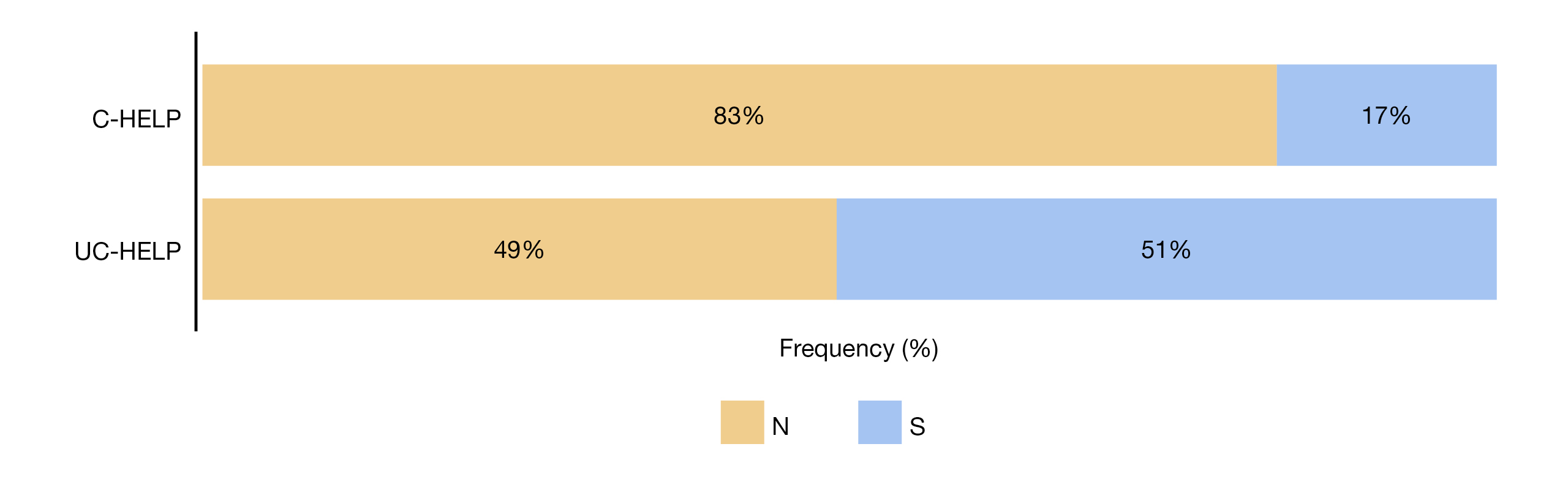

Forehand stroke with forward movement

In forward movements for the forehand stroke, C-HELP players showed an almost even distribution between the neutral stance (N) (48.6%) and the semi-open stance (S) (51.4%). In contrast, UC-HELP players more frequently adopted the semi-open stance (S) (83.3%), which may be related to the need for greater body rotation toward the dominant eye (Figure 6). These differences in the distributions of positions adopted by C-HELP and UC-HELP players were statistically significant (Table 2).

Note. C-HELP: crossed hand-eye laterality profile; UC-HELP: homogeneous hand-eye laterality profile; N: neutral foot position; S: semi-open foot position.

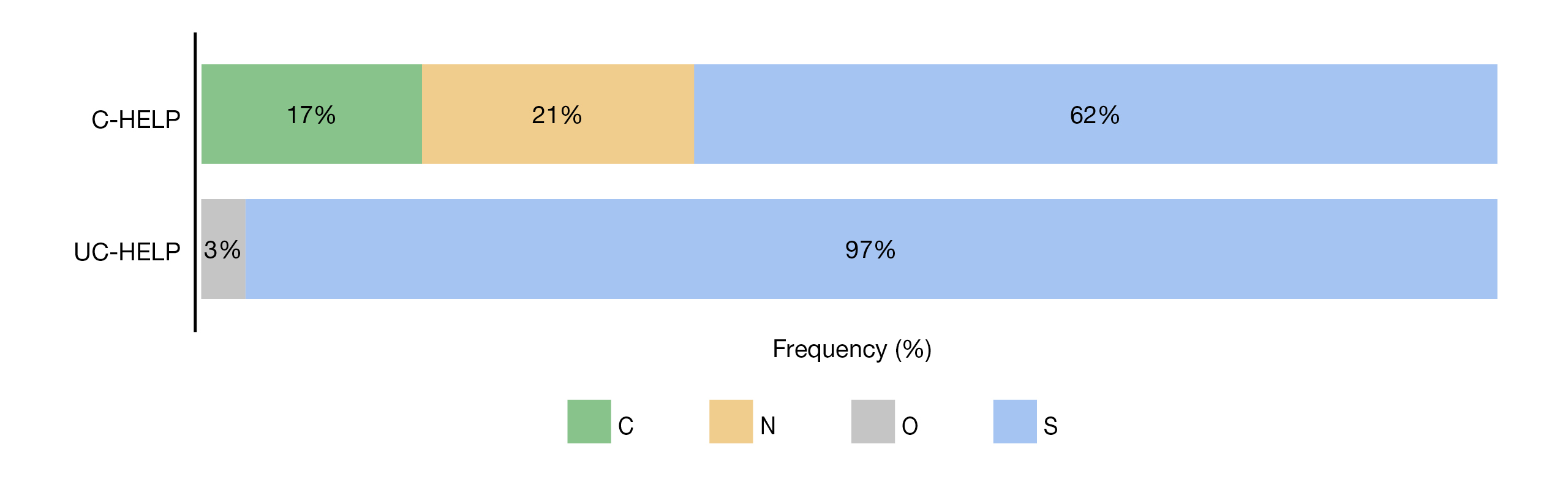

Forehand stroke with backward movement

For the forehand stroke with backward movement, both C-HELP and UC-HELP players tended to use the semi-open stance (S), although with notable differences. UC-HELP players showed a highly consistent use of the semi-open stance (S) (97.3%), whereas C-HELP players adopted a range of stances: closed (C) (16.7%), neutral (N) (20.8%), and semi-open (S) (62.5%) (Figure 7). These differences in the distributions of positions adopted by C-HELP and UC-HELP players were statistically significant (Table 2).

Note. C-HELP: crossed hand-eye laterality profile; UC-HELP: homogeneous hand-eye laterality profile; C: closed foot position; N: neutral foot position; O: open foot position; S: semi-open foot position.

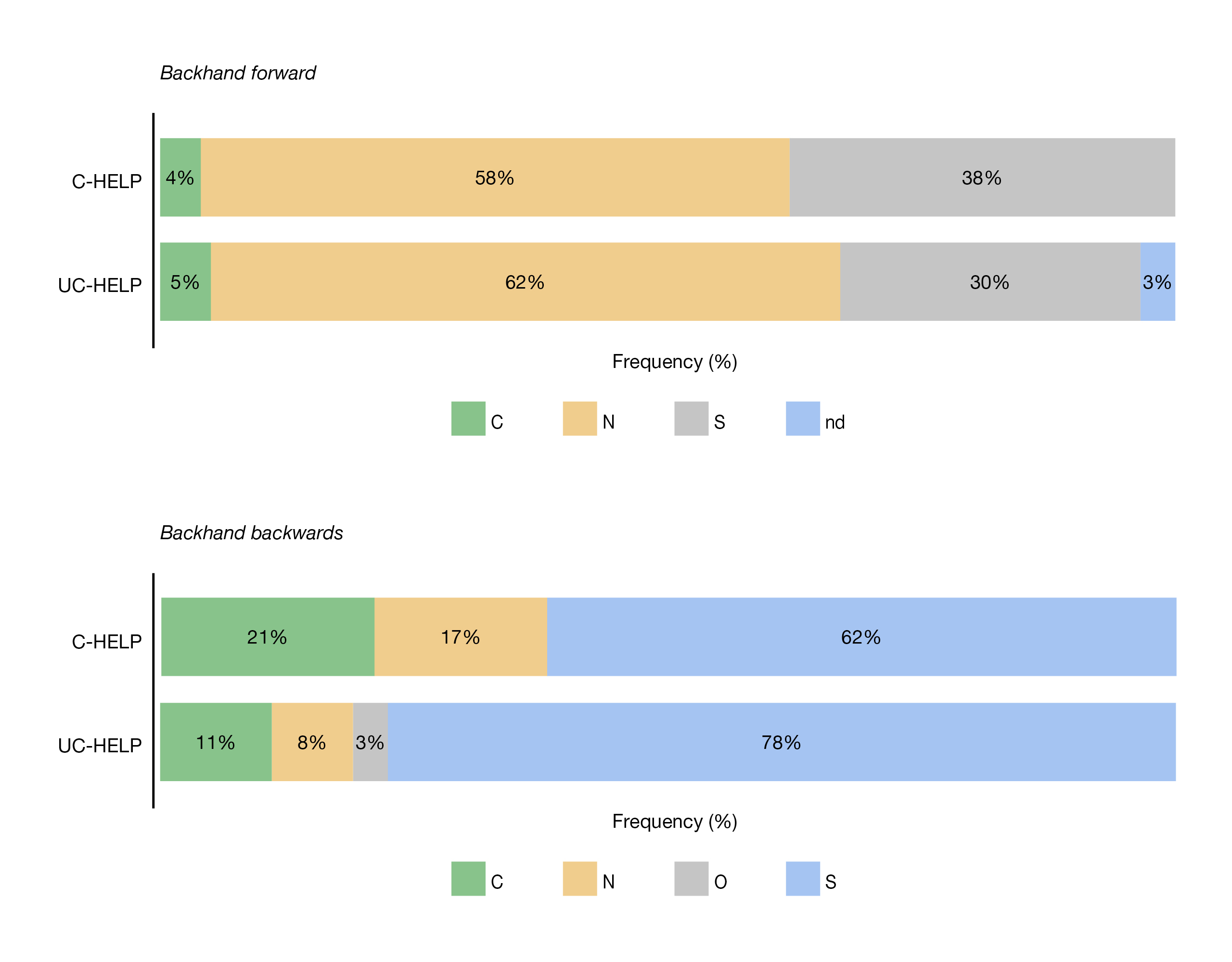

Backhand stroke with forward and backward movement

In backhand strokes with forward and backward movement, the data indicated a general preference for the neutral stance (N) in forward movements (60.7%) and the semi-open stance (S) in backward movements (72.1%) (Figure 8), with no statistically significant differences between C-HELP and UC-HELP profiles (Table 2).

Note. C-HELP: crossed hand-eye laterality profile; UC-HELP: homogeneous hand-eye laterality profile; C: closed foot position; N: neutral foot position; O: open foot position; S: semi-open foot position.

Discussion

This study met its objective of analyzing the reliability of two tests applied in tennis: the HELP assessment test (Laby & Kirschen, 2011; Moreno et al., 2022) and the footwork preference test, based on the instrument used by the Catalan Tennis Federation. Specifically, test-retest and inter-rater reliability of the HELP test were examined, revealing a high level of agreement across time points and between observers. Reliability of the footwork preference test was also analyzed, with high agreement between measurements. In addition, the distribution of HELP profiles was examined in a sample of high-level tennis players, revealing a higher prevalence of crossed profiles (C-HELP) compared with the general population. Finally, the relationship between HELP profile and footwork preferences was explored, revealing specific patterns based on hand-eye laterality. The results are relevant from an applied perspective because the sample comprised players selected by the Catalan Tennis Federation according to level and performance criteria, making it representative of high-level developmental tennis at the regional level and with implications at the national and international levels.

The results for the HELP test demonstrate test-retest reliability in measurements made by the same evaluator at different time points. Furthermore, 100% agreement was obtained for inter-rater reliability. Overall, the HELP test can be considered reliable for assessing hand-eye laterality in tennis players. The relevance of these findings lies in the fact that, for the first time, evidence is provided on the reliability of a standardized protocol for measuring hand-eye laterality in sport. So far, methods used have been inconsistent, with considerable variability in tests for measuring ocular dominance and debate regarding which tests provide accurate assessment of this phenomenon (Bourassa et al., 1999; Laby & Kirschen, 2011; Moreno et al., 2022). In this regard, our results support the use of the proposed test to identify laterality profiles in tennis and other sports.

The footwork preference test showed agreement levels above 90%, and can therefore also be considered suitable for establishing technical profiles of footwork based on laterality and prior movement.

Regarding HELP profile, 42.2% of the tennis players assessed presented a C-HELP profile, indicating a higher concentration than in the general population, where the prevalence of this profile ranges from 10% to 30% (Robinson et al., 1997). This finding is consistent with previous studies that have examined laterality in elite tennis, such as Dallas et al. (2018), who reported 42% C-HELP among the world’s best tennis players. Crossed hand-eye laterality may therefore represent an advantage for performance in tennis. However, further research is needed to provide evidence for this relationship and to clarify the underlying mechanisms. For example, Azémar (2003) suggested that reaction times may be faster for the hand contralateral to the dominant eye in laboratory tasks, which could influence the effectiveness of movements on court, and similarly, Balci et al. (2021) found faster reaction times in UC-HELP swimmers when the contralateral eye remained open. Therefore, the results are consistent with previous studies highlighting the influence of the relationship between ocular and motor laterality on sport movements (Castañer et al., 2016).

Analysis of support preferences by type of movement confirms the existence of distinct patterns based on hand-eye laterality profile. Our results show that the two profiles differ significantly in support preferences for forehand strokes (forward, backward, and lateral) and for backhand strokes with lateral movement. UC-HELP players tend to orient their bodies more frontally in the forehand stroke, whereas C-HELP players prefer open stances in the backhand stroke when moving laterally. This phenomenon is consistent with the observations of Garipuy and Wolff (1999), who suggested that body alignment at impact is influenced by visual dominance, which acts as the player’s perceptual–motor center. Thus, a right-handed player with a dominant right eye can more effectively coordinate the reception of a moving ball to the right side using a frontal stance, whereas in situations where the ball is directed to the left side, the player tends to rotate the body to optimize perception and stroke control. Likewise, players with a C-HELP profile show a greater preference for open stances when performing backhand strokes with lateral movements, whereas they more frequently adopt neutral and semi-open stances in forehand strokes.

These findings provide evidence of the influence of HELP on tennis players’™ motor organization and reinforce the importance of individualizing technical instruction in tennis by adjusting footwork patterns to optimize stroke biomechanics according to HELP profile and each player’s perceptual-motor characteristics.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence for the reliability of the HELP test and the footwork preference test in tennis players and confirms the importance of assessing HELP profile because of its impact on the technical fundamentals of tennis. The results suggest that the hand-eye dominance test is a non-invasive tool that is easy to administer and requires no instruments, and that it may be highly useful in sport and in any context where hand-eye dominance is relevant. Its inclusion in routines for assessing technical aspects of tennis players is therefore recommended, as well as in athletes for whom laterality and hand-eye dominance may be an important factor.

The results obtained in a sample of high-level tennis players are notable for the significant prevalence of the crossed hand-eye laterality profile (C-HELP), at 42.2%, higher than the 10%–30% observed in the general population. This finding supports the idea that C-HELP profiles are over-represented among elite athletes in certain sports such as tennis, as suggested in previous research. In addition, a consistent relationship was identified between HELP and preferences in technical footwork patterns in tennis, specifically in foot position during strokes, with open stances being more common in forehands among UC-HELP players and in backhands among C-HELP players, particularly when balls are hit after lateral movement.

Although we underscore the reliability of the tests used and the inclusion of a large, representative sample of high-level developmental tennis players, it would be valuable to replicate our results with other samples of tennis players, both nationally and internationally, and with older and more advanced players. In our study, the sample was one of convenience, selected by the Catalan Tennis Federation, and the aim was not to analyze differences by gender or manual laterality (right-handed/left-handed), as this would require prior hypotheses and a larger and more segmented sample. Nonetheless, we consider that such analyses represent a relevant line of research to be pursued in the future. The higher prevalence of C-HELP profiles observed among high-level tennis players does not explain the mechanisms underlying this relationship, and further research is needed in this direction.

Future research should also explore the role of other variables, such as perceptual–motor processing speed or decision making in tennis. Likewise, future studies should analyze stroke accuracy based on type of support and laterality profile and examine whether tailoring training to HELP profile can facilitate technical learning and help reduce injury risk, taking into account the potential relationship between certain support patterns and joint overload.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by projects PID2019-107473RB-C21 and PID2022-141403NB-I00 from the Government of Spain (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER, EU) and by grant 2021SGR-00806 from the Government of Catalonia (Spain).

References

[1] Azémar, G. (2003). Chapter V. De l’œil à la main. In L’homme asymétrique (pp. 201–241). Paris: CNRS Éditions. doi.org/10.4000/books.editionscnrs.8724

[2] Bache, M., & Orellana, J. (2014). Laterality and sports performance. Archivos de Medicina del Deporte, 31(161), 200–204. archivosdemedicinadeldeporte.com/articulos/upload/16_rev01_161.pdf

[3] Balci, A., Baysal, S., Kabak, B., Akinoglu, B., Kocahan, T., & Hasanoglu, A. (2021). Comparison of hand-eye dominance and visual reaction time in swimmers. Turkish Journal of Sports Medicine, 56(2), 81–85. doi.org/10.47447/tjsm.0498

[4] Bourassa, D. C., McManus, I. C., & Bryden, M. P. (1996). Handedness and eye-dominance: a meta-analysis of their relationship. Laterality, 1(1), 5–34. doi.org/10.1080/713754206

[5] Castañer, M., Barreira, D., Camerino, O., Anguera, M. T., Canton, A., & Hileno, R. (2016). Goal scoring in soccer: A polar coordinate analysis of motor skills used by Lionel Messi. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00806

[6] Castañer, M., Andueza, J., Hileno, R., Puigarnau, S., Prat, Q., & Camerino, O. (2018). Profiles of motor laterality in young athletes’ performance of complex movements: Merging the MOTORLAT and PATHoops tools. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00916

[7] Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and psychological measurement, 20(1), 37-46. doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104 (Original work published 1960)

[8] Costa, S., Berchicci, M., Bianco, V., Croce, P., Di Russo, F., Quinzi, F., Bertollo, M., & Zappasodi, F. (2023). Brain dynamics of visual anticipation during spatial occlusion tasks in expert tennis players. Psychology of sport and exercise, 65, 102335. doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2022.102335

[9] Dane, S., & Erzurumluoglu, A. (2003). Sex and handedness differences in eye-hand visual reaction times in handball players. The International journal of neuroscience, 113(7), 923–929. doi.org/10.1080/00207450390220367

[10] Dallas, G., Mavvidis, A., & Ziagkas, E. (2018). Investigating the role of ipsilateral and contralateral eye-hand dominance in ATP qualification and tennis serve performance of professional tennis players. International Journal of Sports and Physical Education, 4(2), 37–41. dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-6380.0402005

[11] Díaz-Pereira, M. P., González-Fernández, A., Fernández-Villarino, M. A., Delgado-Parada, J., & López-Araujo, Y. (2024). Exploring the relationships between motor creativity, lateral preference and sport in children. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 155, 19–28. doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2024/1).155.03

[12] Dorochenko, P. (2013). El Ojo Director. Paul Dorochenko.

[13] Garipuy, C., & Wolff, M. (1999). Tennis: rôle de la latéralité oculo-manuelle. EPS: Revue Éducation Physique et Sport, 276, 73–77

[14] Knudson, D., & Kluka, D. (1997). The impact of vision and vision training on sport performance. Journal of Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 68(4), 17–24. doi.org/10.1080/07303084.1997.10604922

[15] Laborde, S., Dosseville, F. E. M., Leconte, P., & Margas, N. (2009). Interaction of hand preference with eye dominance on accuracy in archery. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 108(2), 558–564. doi.org/10.2466/pms.108.2.558-564

[16] Laby, D. M., & Kirschen, D. G. (2011). Thoughts on ocular dominance—Is it actually a preference? Eye and Contact Lens, 37(3), 140–144. doi.org/10.1097/ICL.0b013e31820e0bdf

[17] Landis, J.R., & Koch, G.G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174.

[18] Moreno, M., & Baiget, E. (2024). Nuevas tendencias en el entrenamiento del tenis: Modelo basado en la acción de juego. Edicions i Publicacions de la Universitat de Lleida.

[19] Moreno, M., Capdevila, L., & Losilla, J. (2022). Could hand-eye laterality profiles affect sport performance? A systematic review. PeerJ, 10:e14385. doi.org/10.7717/peerj.14385

[20] Özmen, T., Aydogmus, M., & Yildirim, N. U. (2020). Effects of visual training in tennis performance in male junior tennis players: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 60(3), 493–499.

[21] Pearson, K. (1900). On a new test of the law of the normal distribution. Philosophical Magazine, 50(334), 418–423.

[22] Peters, M., & Campagnaro, P. (1996). Do lateral preferences influence the selection of sport activities? Perceptual and Motor Skills, 82(3_suppl.), 1168–1170.

[23] Razeghi, R., Shafie Nia, P., Shebab Bushehri, N., & Maleki, F. (2012). Effect of interaction between eye-hand dominance on dart skill. Journal of Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, 4(2), 6–12. doi.org/10.5897/JNBH11.027

[24] Robinson, S., Jacobsen, S., & Heintz, B. (1997). Crossed hand-eye dominance. Journal of Optometric Vision Development, 28(4), 235–245

[25] Shim, J., Carlton, L. G., Chow, J. W., & Chae, W.-S. (2005). The use of anticipatory visual cues by highly skilled tennis players. Journal of Motor Behavior, 37(2), 164–175. doi.org/10.3200/JMBR.37.2.164-175

[26] Subhashree, E., & Farzana, S. F. M. (2025). Correlational analysis of a serve with hand-eye laterality profile among professional tennis players in Chennai. Journal of Neonatal Surgery, 14(1s), 746–747. doi.org/10.52783/jns.v14.1598

[27] Williams, A. M., & Davids, K. (1998). Visual search strategy, selective attention, and expertise in soccer. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 69(2), 111–128. doi.org/10.1080/02701367.1998.10607677

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: June 6, 2025

Accepted: September 23, 2025

Published: January 1, 2026

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en