ARS Conceptual Framework for AI-Driven Systematic Reviews in Sports Science and Medicine

*Correspondència: Tiago Fernandes tiagomgfernandes@ outlook.com

Citació

Fernandes, T., Castañer, M., & Camerino, O. (2025). ARS conceptual framework for AI-driven systematic reviews in sports science and medicine. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 161, 68-74. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2025/3).161.08

1992Visites

Abstract

Sports coaching and medical teams require valuable, accessible information to support their practices, and systematic reviews offer a well-established, trusted method of producing synthesised evidence to inform their decision-making. However, it entails significant costs due to the required time and human resources, while immediate and systematic evidence synthesis methods remain scarce. Despite the recent advances in machine learning and natural language processing in making information task automation viable, a notable gap seems to exist in their integration and within the principles of the scientific method. Therefore, this scientific note presents the structure and conceptualisation of a proposed framework to automate the workflow of systematic reviews, illustrated through an early implementation within a web application, namely Automatic Research Synthesis (ARS), intending to reduce the time and effort required by researchers and practitioners in sports science and medicine.

Introduction

Systematic reviews (SRs) entail a process of searching, screening, evaluating, and summarising evidence to support decision-making with reliable and unbiased findings on a specific topic (Cooper et al., 2019), which practitioners can turn to obtain actionable information. However, its production is often slow and expensive, motivating researchers and engineers to automate SR tasks. Compared to data collection methods in sports science and medicine, where comprehensive pipelines are commonly available (e.g., real-time position-tracking monitoring and analysis systems; Tang et al., 2025), SR automation appears to be fragmented across tasks (Johnson et al., 2022; Marshall & Wallace, 2019; Tsafnat et al., 2014; van de Schoot et al., 2021).

Advancements in SR automation have been applied to the selection of primary studies, bias assessment, and automatic text extraction using machine learning (ML) and natural language processing (NLP) techniques to achieve performance comparable to manual assessments (Marshall & Wallace, 2019; Tsafnat et al., 2014; van de Schoot et al., 2021). For instance, Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016) and RobotReviewer (Marshall et al., 2016) have shown improvements in predicting included studies and bias assessment, respectively. Moreover, pre-trained models based on transformer deep-learning model architectures using zero-shot classification, which reduces data scarcity issues, have also shown promising results in screening tasks (Moreno-Garcia et al., 2023). In addition, recent studies have explored the use of ChatGPT in conducting systematic reviews, showing that prompt engineering in generative pre-trained transformer models can help with significant results in articles’ screening and text extraction (Alshami et al., 2023; Khraisha et al., 2024). Other services that deliver a certain level of accuracy, even though they focus on general literature reviews, include Scite, Elicit, and SciSpace AI research assistants, which process searches, contextualise citations, extract data, and synthesise papers (Fenske & Otts, 2024; Nicholson et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2023).

Although the literature mentions tools for assistance, semi-automation, or full automation for specific tasks, it appears to remain a gap in integrating them into a continuous workflow (Johnson et al., 2022; Marshall & Wallace, 2019; Tsafnat et al., 2014; van de Schoot et al., 2021). Such fragmentation hinders the application of the scientific method, resulting in a need to use various paid tools or services, which may introduce challenges related to consistency and productivity (Sanchez et al., 2015). Related work in streamlining scientific research exists in experimental or original research settings. For example, AI co-scientist (Gottweis et al., 2025) and AI Scientist (Lu et al., 2024) are fully automated systems using multiple Large Language Models (LLM) agents to perform end-to-end research, from defining questions or hypotheses, conducting literature reviews to drafting and reporting results. While promising in its context, these systems seem to lack specialisation in systematic reviews under established guidelines such as the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Page et al., 2021).

Therefore, this scientific note provides the structure and theoretical foundation of a purposed conceptual framework for an end-to-end process incorporating artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities, upon which a web application (WA) Automatic Research Synthesis (ARS) has been developed to demonstrate the workflow automation of systematic reviews, report its development, discuss the challenges encountered and its significance.

Conceptual Framework

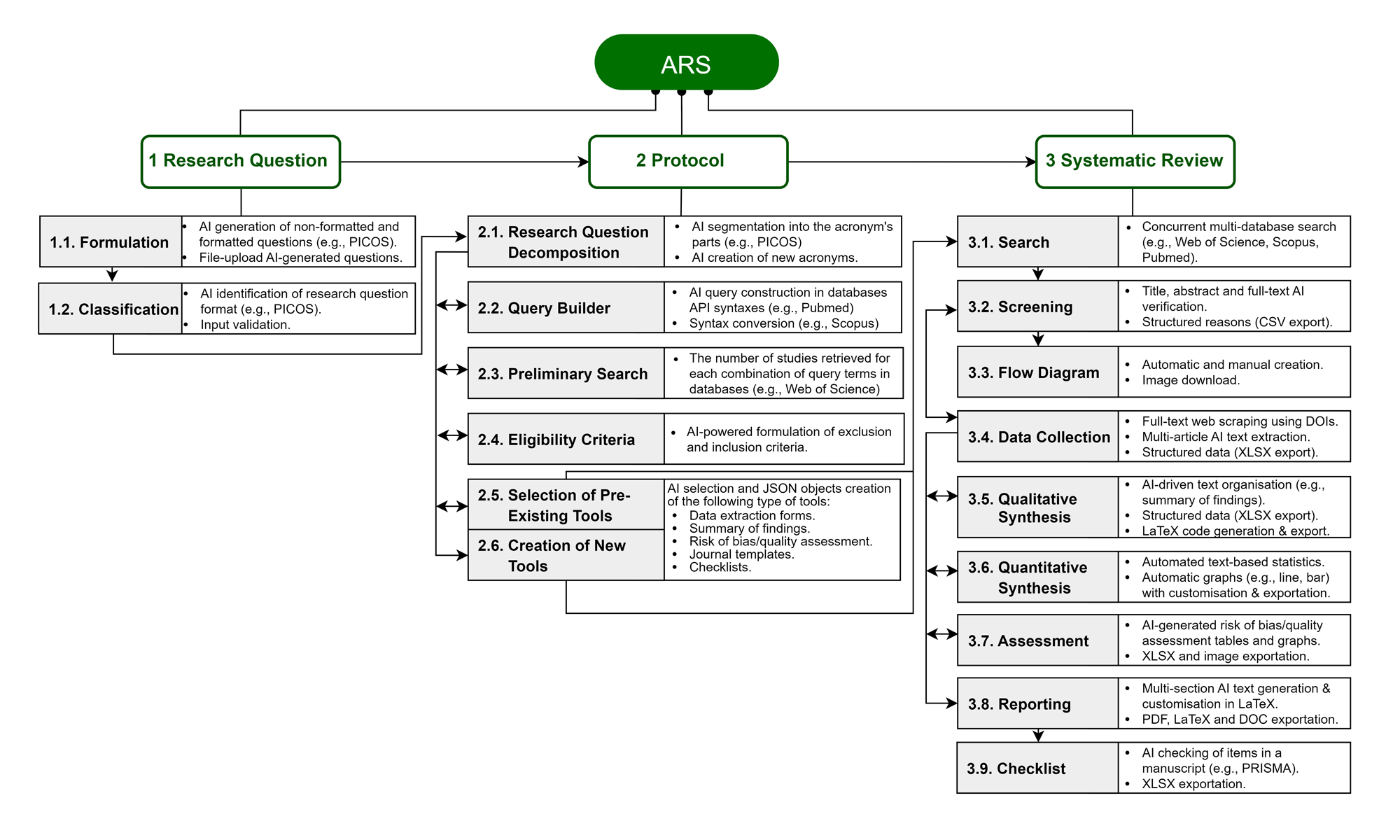

The conceptual framework integrates three main conceptual modules according to systematic review guidelines and best practices (Cooper et al., 2019; Page et al., 2021; Tsafnat et al., 2014), namely (i) Research Question, (ii) Protocol and (iii) Systematic Review (Figure 1). It automates the workflow to produce a final output while allowing manual editing and supervision if needed. Technically, it is specifically designed to use LLM with Few-Shot Learning (FS) and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), employing a Structured Query Language (SQL) database for vector storage, retrieving forms and templates in JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) structure. Concretely, it enables the export of datasets, documents, and images in XLSX, DOC, and PNG formats.

Note. ARS = Automatic Research Synthesis; AI = artificial intelligence; PICOS = Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design; PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Due to space limitations, AI describes general machine learning and natural language processing techniques such as large language models and retrieval augmented generation. The numbered green blocks, grey areas and white sections within the grey-white blocks represent the conceptual modules, functionalities and features, respectively.

Research Question Module

The Research Question module allows new research questions to be created and validated before passing to the Protocol module, which could follow a specific format, e.g., Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design (PICOS). In addition, it generates research questions with a particular topic of interest using file upload and prompts, similar to Microsoft Copilot or other AI assistants (Figure 1, Boxes 1.1-1.2).

Protocol Module

The Protocol module’s main sections include search methods for identifying studies, e.g., query building, eligibility criteria for selecting studies, and forms or tools for data collection and analysis (Cooper et al., 2019; Page et al., 2021; Tsafnat et al., 2014). The Research Question Decomposition breaks down the research question into the corresponding parts of the format and determines its suitability using pre-determined contextualised prompts. Based on that classification, it builds queries using the syntax of Scopus, Pubmed, Web of Science and EBSCOhost, performs preliminary searches, generates the eligibility criteria, and selects or creates the tools, such as data extraction forms, summary of findings (SoF) tables, risk of bias and quality assessment, checklists and journal templates, which are followed by the review generation system and selected depending on the context of the previously formulated research question (Figure 1, Boxes 2.1-2.6, respectively).

Systematic Review Module

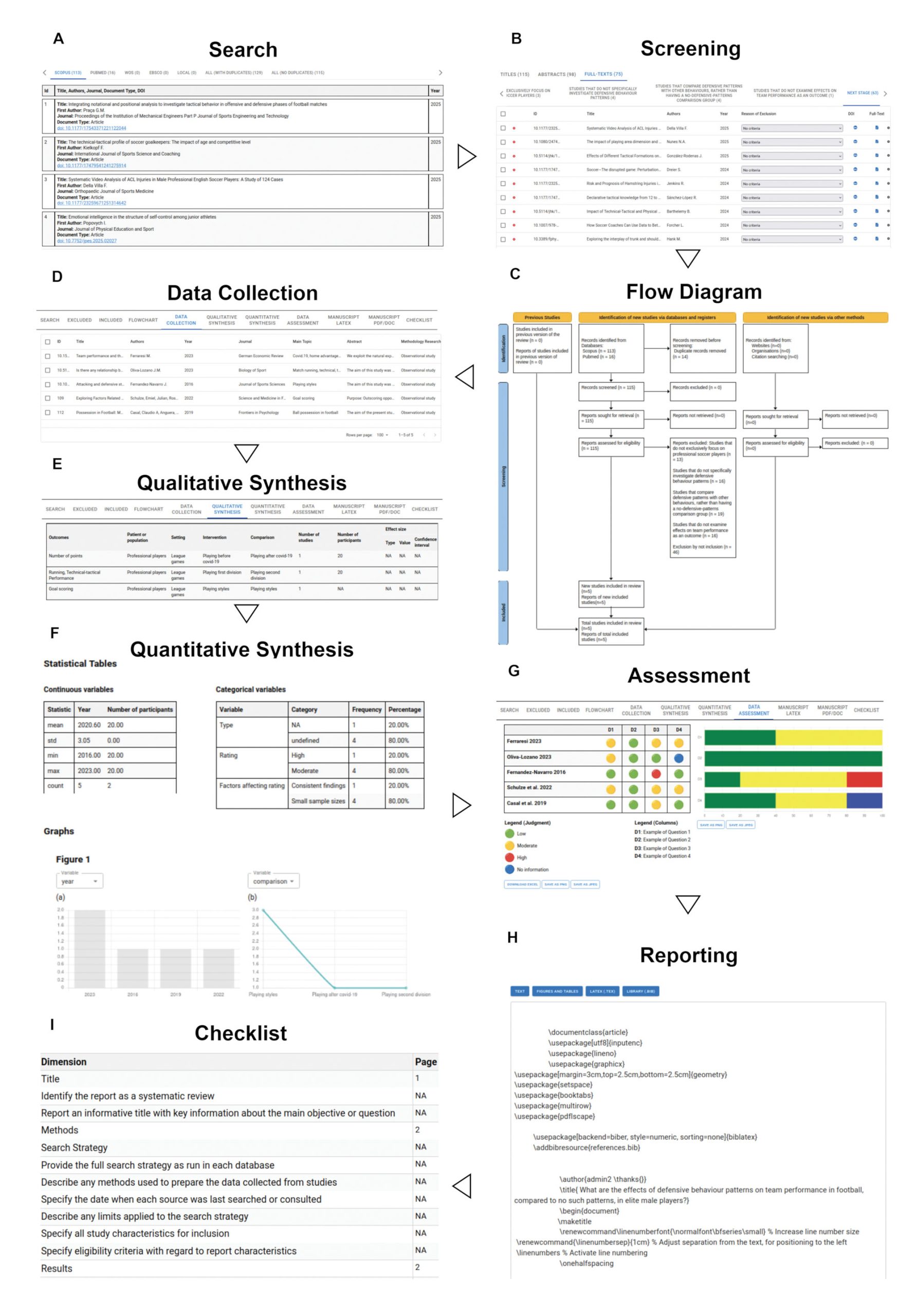

The SR module integrates the main stages recommended by literature as the following functionalities (Cooper et al., 2019; Page et al., 2021; Tsafnat et al., 2014): (i) Search, (ii) Screening, (iii) Flow Diagram, (iv) Data Collection, (v) Qualitative Synthesis (vi) Quantitative Synthesis, (vii) Assessment, (viii) Reporting, and (ix) Checklist (Figure 1 and 2). The Search functionality uses the protocol’s queries to retrieve search results from Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science and EBSCOhost using application programming interfaces (APIs) (Figure 1, Box 3.1; and Figure 2, Part A). These features ensure that researchers can access the most relevant, up-to-date literature and manage articles more efficiently. In addition, researchers can add their articles to perform local searches. Further, the Screening functionality identifies duplicates and filters out irrelevant articles by analysing sequentially titles, abstracts, and full texts according to the protocol’s exclusion and inclusion criteria (Figure 1, Box 3.2; and Figure 2, Part B). The results are reported on the Flow Diagram functionality (Figure 1, Box 3.3; and Figure 2, Part C), which is aligned with PRISMA 2009 and 2020 (Page et al., 2021).

Note. Each component was cropped from the original interface to fit the image for better incorporation. Data used, image arrangements, and selective cropping of functionalities images were employed for illustration purposes. Each letter represents the functionality labelled immediately below the box.

Data Collection, Qualitative and Quantitative Synthesis functionalities operate similarly but independently, relying on full-text scraping using exclusively digital object identifiers to ensure accessibility compliance or locally stored reference papers for customisation and flexibility. Subsequently, the data is extracted and structured using RAG with customised, pre-defined prompts and the selected extraction forms, then transferred to a vector storage and made available in a spreadsheet format (Figure 1, Box 3.4; and Figure 2, Part D).Further, the data is organised into a SoF table, supported by descriptive statistics such as word count visualisations (e.g., line, bar, and network graphs), with future developments potentially featuring advanced statistical analyses such as meta-analysis (Figure 1, Boxes 3.5-3.6; and Figure 2, Parts E-F).

Afterwards, the Assessment functionality displays a table and a stacked bar graph with the risk of bias and quality assessments of included studies completed by an AI agent (Figure 1, Box 3.7; and Figure 2, Part G). However, some assessments must also require rule-based algorithms with LLM-FS for specific tools, as is the case of the ROBINS-I (Sterne et al., 2016). The images and tables generated by all previous functionalities are passed to the Reporting functionality to integrate into a LaTeX code for manuscript draft formatted according to the selected journal’s template and guidelines, such as specific sections or word count limits. The manuscript can be exported as a PDF or Word document (Figure 1, Box 3.8; and Figure 2, Part H). Finally, the Checklist functionality verifies each item on a checklist previously defined in the protocol, including but not limited to the PRISMA 2020 statement (Page et al., 2021). Also available in PDF, which can be used for submission alongside the manuscript, as often required by journals (Figure 1, Box 3.9; and Figure 2, Part I).

Early Implementation and Challenges

The conceptual framework was initially implemented within a WA, which had been used to generate a protocol for a previous publication (Fernandes et al., 2024). However, several challenges must be addressed before the system can be fully operational and accessible to researchers. Consistent outputs with high accuracy are required to enhance data trustworthiness, reduce errors, and enable insightful, practical applications in sports science and medicine, as well as in other scientific domains. In this regard, there is a need to fine-tuning models using human labelling on specific topics, which is resource-intensive, but can be addressed by data sharing systematic review task files with annotation guidelines, as well as the comparison of the efficiency and effectiveness of answers with manual or other automation software tools (Khraisha et al., 2024; Moreno-Garcia et al., 2023; Tsafnat et al., 2014).

Despite ARS being implemented as a WA, it is designed for local access and to be compatible with different operating systems and hardware resources. However, transitioning to an online environment requires a more robust infrastructure to support multiple users, LLM and RAG. Third-party API integrations (e.g., OpenAI) could become feasible if challenges such as managing multiple API keys and resource limitations are addressed, for which recent multi-agent system architectures with supervisor and safeguard agents offer potential solutions (Gottweis et al., 2025; Lu et al., 2024). In ARS WA, the framework was implemented using a distributed multi-agent architecture to reduce complexity and accommodate limited hardware capabilities. However, similar to the previous works, more specialised, cooperative or competitive multi-agent architectures can be incorporated.

Lastly, the early implementation of the conceptual framework relies on web scraping to access available full-text documents, which introduces some instability and regulatory concerns that can be improved with third-party tools (e.g., CORE or Crossref APIs). ARS WA was implemented to be customised to sports science and medicine researchers’ needs and suggestions, though future investigations are required to evaluate the viability, ethical considerations, and legal implications of these integrations.

Impact and Significance

The conceptual framework offers diverse opportunities for research investigation and innovation by significantly decreasing the researchers’ time in the process of creation and updates of SRs. For instance, it can generate and classify new research questions linked to protocol development and their direct relationship to the review, which can be extended and incorporate journal guidelines and tools from the literature (Johnson et al., 2022). As for sports field practices, data velocity, veracity and value are considered to help multidisciplinary teams synthesise evidence-based knowledge and support decision-making.

Furthermore, the conceptual functionalities of the framework have constantly been cited and used in various academic and professional fields (e.g., Ouzzani et al., 2016), revealing a diverse public interest and wide application. Embracing modern technologies like ML and NLP while utilising structured outputs that can be directly used for fine-tuning and training models has the potential to enhance task response accuracy and sophistication (Marshall et al., 2016; Marshall & Wallace, 2019; Ouzzani et al., 2016; Tsafnat et al., 2014; van de Schoot et al., 2021). Further, the standardising processes within automating tasks promote transparency, objectivity, and replication (Marsden & Pingry, 2018).

Conclusions

The proposed conceptual framework in this scientific note streamlines research synthesis tasks using AI capabilities such as literature searching, screening, data collection, risk of bias and quality assessment, synthesis and manuscript writing. The work can be performed simultaneously or step-by-step with manual intervention, offering widespread usability, software integration, and research opportunities while considering adaptable hardware requirements. Although ARS WA still requires validation and formal testing before being fully introduced, this work represents an initial step towards its practical deployment and broader adoption by laying the foundation, promoting discussion and identifying key challenges for future development.

Declarations

This is an original work that has not been previously published, in whole or in part, is not under review in any other publication, and all authors take responsibility for its final version, having contributed to its development, with the understanding that acceptance for publication entails the transfer of all authorship rights to the National Institute of Physical Education of Catalonia (INEFC), which holds exclusive rights to edit, publish, or reproduce the text and images of the article in any format, but not the software or the source code, algorithms, data, and any other related materials to it described within, which remain the intellectual property of TF.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support of the Department of Research and Universities of the Generalitat de Catalunya to the Research Group and Innovation in Designs (GRID). Technology and multimedia and digital application to observational designs (Code: 2021 SGR 00718). The National Institute of Physical Education of Catalonia (INEFC). The Spanish Government Project: Integración entre datos observacionales y datos provenientes de sensores externos: Evolución del software LINCE PLUS y desarrollo de la aplicación móvil para la optimización del deporte y la actividad física beneficiosa para la salud [EXP_74847] (2023). Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Consejo Superior de Deportes. The Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia) by supporting Tiago Fernandes with an individual doctoral grant (2021.0581.BD).

Funding

This work is funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia) (2021.0581.BD).

Referències

[1] Alshami, A., Elsayed, M., Ali, E., Eltoukhy, A. E. E., & Zayed, T. (2023). Harnessing the power of ChatGPT for automating systematic review process: methodology, case study, limitations, and future directions. Systems, 11(7), 351, 1-37. doi.org/10.3390/systems11070351

[2] Cooper, H., Hedges, L. V., & Valentine, J. C. (2019). Handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (3rd ed.). Russell Sage Foundation.

[3] Fenske, R. F., & Otts, J. A. A. (2024). Incorporating generative AI to promote inquiry-based learning: comparing Elicit AI research assistant to PubMed and CINAHL Complete. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 43(4), 292-305. doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2024.2403272

[4] Fernandes, T., Rago, V., Castañer, M., & Camerino, O. (2024). Ranking sports science and medicine interventions impacting team performance: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies in elite football. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 10(3), e002196. doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2024-002196

[5] Gottweis, J., Weng, W.-H., Daryin, A., Tu, T., Palepu, A., Sirkovic, P., Myaskovsky, A., Weissenberger, F., Rong, K., Tanno, R., Saab, K., Popovici, D., Blum, J., Zhang, F., Chou, K., Hassidim, A., Gokturk, B., Vahdat, A., Kohli, P., . . . Natarajan, V. (2025). Towards an AI co-scientist. arXiv. doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.18864

[6] Johnson, E. E., O’Keefe, H., Sutton, A., & Marshall, C. (2022). The Systematic Review Toolbox: keeping up to date with tools to support evidence synthesis. Systematic Reviews, 11, 258. doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-02122-z

[7] Khraisha, Q., Put, S., Kappenberg, J., Warraitch, A., & Hadfield, K. (2024). Can large language models replace humans in systematic reviews? Evaluating GPT -4’s efficacy in screening and extracting data from peer-reviewed and grey literature in multiple languages. Research Synthesis Methods, 15(4), 616-626. doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1715

[8] Lu C., Lu C., Lange R. T., Foerster J., Clune J., & Ha D. (2024). The AI scientist: Towards fully automated open-ended scientific discovery. arXiv. doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2408.06292

[9] Marsden, J. R., & Pingry, D. E. (2018). Numerical data quality in IS research and the implications for replication. Decision Support Systems, 115, A1-A7. doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2018.10.007

[10] Marshall, I. J., Kuiper, J., & Wallace, B. C. (2016). RobotReviewer: evaluation of a system for automatically assessing bias in clinical trials. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 23(1), 193-201. doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocv044

[11] Marshall, I. J., & Wallace, B. C. (2019). Toward systematic review automation: a practical guide to using machine learning tools in research synthesis. Systematic Reviews, 8(1), 163. doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1074-9

[12] Moreno-Garcia, C. F., Jayne, C., Elyan, E., & Aceves-Martins, M. (2023). A novel application of machine learning and zero-shot classification methods for automated abstract screening in systematic reviews. Decision Analytics Journal, 6, 100162. doi.org/10.1016/j.dajour.2023.100162

[13] Nicholson, J. M., Mordaunt, M., Lopez, P., Uppala, A., Rosati, D., Rodrigues, N,. P., Grabitz, P., & Rife, S. C. (2021). scite: A smart citation index that displays the context of citations and classifies their intent using deep learning. Quantitative Science Studies, 2(3), 882-898. doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00146

[14] Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5, 210. doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

[15] Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., . . . Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, 71. doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

[16] Sanchez, H., Robbes, R., & Gonzalez, V. M. (2015). An empirical study of work fragmentation in software evolution tasks. 2015 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Software Analysis, Evolution, and Reengineering (SANER), 251-260. doi.org/10.1109/SANER.2015.7081835

[17] Sterne, J. A. C., Hernán, M. A., Reeves, B. C., Savović, J., Berkman, N. D., Viswanathan, M., Henry, D., Altman, D. G., Ansari, M. T., Boutron, I., Carpenter, J. R., Chan, A.-W., Churchill, R., Deeks, J. J., Hróbjartsson, A., Kirkham, J., Jüni, P., Loke, Y. K., Pigott, T. D., . . . Higgins, J. P. T. (2016). ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ, 355, i4919. doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

[18] Tang, X., Long, B., & Zhou, L. (2025). Real-time monitoring and analysis of track and field athletes based on edge computing and deep reinforcement learning algorithm. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 114, 136-146. doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2024.11.024

[19] Tsafnat, G., Glasziou, P., Choong, M. K., Dunn, A., Galgani, F., & Coiera, E. (2014). Systematic review automation technologies. Systematic Reviews, 3, 74. doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-74

[20] van de Schoot, R., de Bruin, J., Schram, R., Zahedi, P., de Boer, J., Weijdema, F., Kramer, B., Huijts, M., Hoogerwerf, M., Ferdinands, G., Harkema, A., Willemsen, J., Ma, Y., Fang, Q., Hindriks, S., Tummers, L., & Oberski, D. L. (2021). An open source machine learning framework for efficient and transparent systematic reviews. Nature Machine Intelligence, 3(2), 125-133. doi.org/10.1038/s42256-020-00287-7

[21] Wu, C., Varghese, A. J., Oommen, V., & Karniadakis, G. (2023). GPT vs human for scientific reviews: a dual source review on applications of ChatGPT in science. arXiv. doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2312.03769

ISSN: 2014-0983

Rebut: 19 de juliol de 2024

Acceptat: 20 de febrer de 2025

Publicat: 1 de juliol de 2025

Editat per: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). Aquest article està disponible a la url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. Aquest treball està publicat sota una llicència Internacional de Creative Commons Reconeixement 4.0. Les imatges o qualsevol altre material de tercers d’aquest article estan incloses a la llicència Creative Commons de l’article, tret que s’indiqui el contrari a la línia de crèdit; si el material no s’inclou sota la llicència Creative Commons, els usuaris hauran d’obtenir el permís del titular de la llicència per reproduir el material. Per veure una còpia d’aquesta llicència, visiteu https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ca