Systematic Review of Social Influences in Sport: Family, Coach and Teammate Support

*Corresponding author: Larissa Fernanda Porto Maciel larissa.maciel10@edu.udesc.br

Cite this article

Porto Maciel, L.F., Krapp do Nascimento, R., Milistetd, M., Vieira do Nascimento, J. & Folle, A. (2021) Systematic Review of Social Influences in Sport: Family, Coach and Teammate Support. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 145, 39-52. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2021/3).145.06

Abstract

The objective of this study was to analyse the scientific publications on the influence of social agents in sport, to identify the types (emotional, informative, tangible) and levels (positive, indifferent, negative) of social support provided to athletes by family members, coaches and teammates. This systematic research was completed by means of a search on the PsycInfo, ProQuest, SportDiscus, Scopus and Web of Science databases and reference lists of systematic reviews on social support in sport. The PRISMA checklist was used to conduct the study, and the study quality analysis was implemented using the STROBE Statement. The PECOS criteria were used in the eligibility of studies found based on the terms applied in the search strategy. The 31 studies selected examined the perception of the three stages of sports training (diversification, specialization, investment) of team and individual sport athletes. The main conclusion is that advances in research into social support have generated a diverse body of evidence, revealing a focus on the analysis of family social support. Family members were identified as the most prevalent social support providers, offering athletes unique forms of emotional, informative and tangible support from positive and negative. Coaches played a significant role in emotional and informative support and teammates in emotional support. It is concluded that positive levels of emotional, informative and tangible support from social agents are key in solidifying athletes’ desire to stay in and prolong their involvement with the sport.

Introduction

Interpersonal relationships are one of the main factors that determine the quality of athletes’ experiences in sport (Coutinho et al., 2018). Accordingly, understanding social influences has been considered one of the most relevant topics in predicting sports performance (Goldsmith, 2004), which is influenced by the result of interaction with social agents in addition to experiences and quality training, as well as by the athlete’s innate talent.

In terms of social support in sport, athletes have three main sources of influence as their athletic career progresses: family members; coaches and teammates. These social agents form a complex and multifaceted social network that may not influence or may have positive and/or negative effects on athletes’ sports experiences (Côté et al., 2003; Côté et al., 2016; Sheridan et al., 2014), as they contribute to the creation of a motivational climate, defined through their behaviours, values, attitudes and support (Camerino et al., 2019; Puigarnau et al., 2016) that affects the way athletes interact and perceive their involvement with sport (Atkins et al., 2013). For this reason, the sequence explains the three main social agents and how they contribute to the involvement of athletes in sport.

Social support

“Social support” is a term commonly used in the literature to describe a group of distinct, albeit interrelated, phenomena (Goldsmith, 2004). In the context of sports, it is a multidimensional construct that has been employed to describe the overall quality of relationships through perceived, available or received support and the individual’s social network (Rees & Hardy, 2000).

There are several types of social support (Goldsmith, 2004), although three specific types have been suggested as being particularly relevant in sport: emotional; informative and tangible (Cutrona & Russell, 1990; Holt & Dunn, 2004;). Emotional support refers to forms of care and encouragement, leading a person to feel loved and protected by others (e.g., motivation and affection). Information support includes receiving information and advice about different situations (e.g., feedback and tips), while tangible support includes concrete assistance received (e.g., logistical and financial support) (Holt & Dunn, 2004; Cutrona & Russel, 1990). Thus, the positive development of athletes through sport will depend on their relationships with social agents, the type of support and how it is perceived by the athlete.

Social agents

The family is regarded as a primary socializing agent through which children develop their own identities and learn the norms and values of the society in which they live (Kubayi et al., 2014). Most of the time, it is the family that provides the child with the first opportunity to play a sport and also has a significant impact on the child’s decision to pursue or give up a sport (Nunomura & Oliveira, 2013). Therefore, from the moment the child takes up a sport, through to their initial accomplishments, parents bring a significant influence to bear upon their sporting career (Dunn et al., 2016; Sheridan et al., 2014).

In addition to the family, the sports coach occupies a position of power and leadership that is seen as central to determining athletes’ experiences (Kassing et al., 2004; Mora et al., 2014; Nascimento Junior et al., 2020). As young athletes engage more systematically in sport, coaches become a substantial source of influence, while parents gradually move more into the background, playing a less directive role in their children’s sports (Pérez-González et al., 2019; Wylleman & Lavallee, 2004). Thus, the support and the quality of the coach-athlete relationship have been regarded as core elements in developing a career in athletics (Jowett & Cockerill, 2003) and consequently a key aspect in achieving success in sports (Riera et al., 2017).

Despite the significant influence exercised by the family and the coach, there comes a time when youth athletes start to spend more time with their peers in the sporting environment. During this period, usually in adolescence, peer influence becomes increasingly important to athletes (Côté et al., 2016; Mora et al., 2014) in sport and in other areas of their life (Holt & Sehn, 2008; Sanz-Martín, 2020; Scott et al., 2019). Teammates constitute a social network that enables the sharing of goals, lifestyles, difficulties and building a sense of relationship among members, besides the potential for providing positive and/or negative psychosocial experiences throughout involvement in sport (Fraser-Thomas & Côté, 2009; Scott et al., 2019), influencing the athlete’s engagement and their decision to continue to do or give up sport (Fraser-Thomas et al., 2008a).

Based on the perspective of social support in sport, scientific production about social influences has been seen to grow considerably over the years (Cranmer & Sollitto, 2015; Folle et al., 2018; Keegan et al., 2010). In general, studies have emphasized that athletes are more likely to achieve positive results (high performance, a successful sports career) when they are encouraged and supported by positive feedback and are supported by family members and coaches that encourage autonomy (Dunn et al., 2016) and by teammates who assist in their personal and moral development (Valero-Valenzuela et al., 2020).

In addition to social influences, sports development models have been put forward in order to glean a better understanding and determination of the involvement of young people in sport, including the Sports Participation Development Model – DMSP (Côté, 1999; Côté et al., 2003). The DMSP proposes that young people develop through stages with specific characteristics and sequential age groups. These stages are related to initial diversification into sports activities (up to 12 years), specialization in one sport (13 to 15 years) and investment in a specific sport focusing on performance (over 16 years) (Côté et al., 2003).

Although important research has been conducted into social influences, there is a scarcity of systematic review studies that offer an integrative view of existing empirical knowledge, focusing on support from the three main social agents (family members, coaches and teammates) and the type (emotional, informative and tangible) and the level (positive, indifferent and negative) of the support provided to athletes. Thus, as already noted by systematic reviews on the topic (Bremer, 2012; Sheridan et al., 2014), such studies broaden our understanding of the topic and provide an opportunity for researchers to share available evidence by identifying appropriate theories to develop future research directions and intervention strategies, as well as to raise awareness of the range of research methods employed in the area of study and detect what research is still needed.

In this scenario, this review sets out to analyse scientific publications on the influence of social agents on sport to identify the types and levels of support provided to athletes by family members, coaches and teammates. In accordance with this purpose and with the literature on the subject, four hypotheses were formulated for this study: a) family members provide mostly emotional and tangible support; b) coaches provide predominantly informative support; c) teammates provide greater emotional support; and d) support from social agents is perceived predominantly by athletes as positive.

Methodology

Research protocol

For the preparation of this systematic review, the criteria recommended by the Declaration Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009) were followed, which provide a guideline for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Moher et al., 2015). To increase transparency in the review process and to disseminate and reduce the unintended duplication of systematic reviews, the protocol of this research was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO – CRD42019114096) database. Registration gives entitlement to the permanent documentation of 22 mandatory (plus 18 optional) items on the preparation and conduct of a systematic a priori review, assisting in the accuracy, completeness and accessibility of the studies (Moher et al., 2015).

Information sources and search strategy

A rigorous search of the literature was conducted in the following electronic databases: PsycInfo (APA); ProQuest (Physical Education Index); SportDiscus via EBSCO; Scopus (Elsevier); and Web of Science – Core Collection (Clarivate Analytics). The choice of these databases was based on their use of systematic reviews related to social support in the area of Sport Sciences (Bremer, 2012; Sheridan et al., 2014), in which a manual secondary search was performed in reference lists to source additional studies.

In each search engine, terms related to the study topic were input (“Influence” OR “Support” OR “Involvement”) and were combined with population-related terms (“Athlete” OR “Parents” OR “Family” OR “Coach” OR “Peers” OR “Teammate”) and research context (Sport), using the Boolean operator AND to combine terms related to topic, population and context (“Influence” OR “Support” OR “Involvement” AND “Athlete” OR “Parents” OR “Family” OR “Parent Coach” OR “Teammate” AND “Sport”).

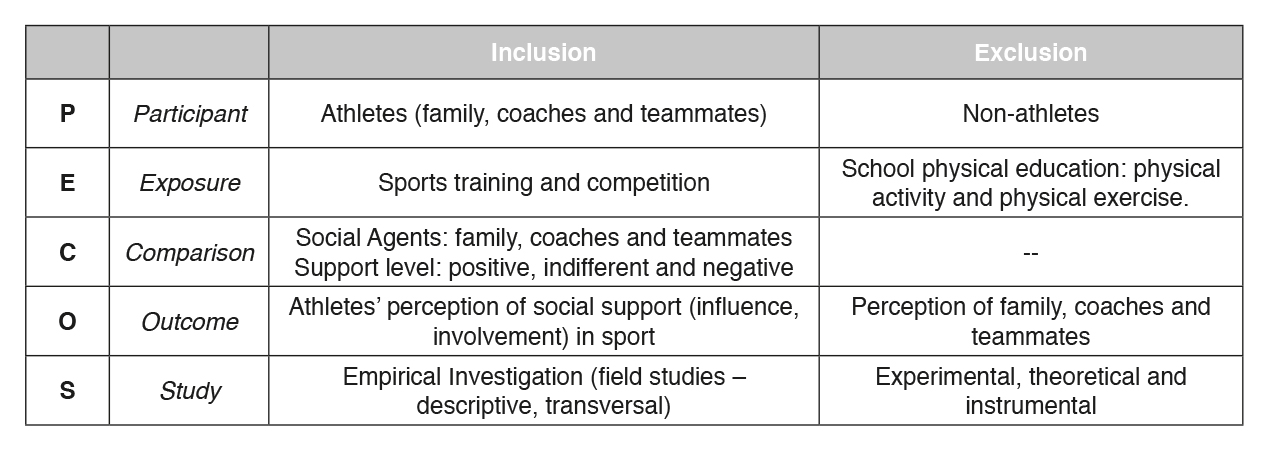

Eligibility criteria

The criteria governing the eligibility of the articles sourced followed the literature recommendations for such studies (Meline, 2006). We considered, for the purpose of analysis, original articles in English and from the period between 2001 and 2018 (21st century) that presented an abstract and a full text available online.

The eligibility assessment was carried out in a standardized and independent fashion by two researchers who were graduates in Physical Education, were attending the Human Movement Sciences Graduate Program and had with experience in the production of scientific research and systematic reviews. Disagreements were solved by consensus, with the assistance of a third investigator when a consensus could not be reached (Prat et al., 2019). Studies were included and excluded following the PRISMA PECOS criteria (Figure 1). After the searches had been performed in the databases, duplicate studies were eliminated. Finally, three steps were followed for selecting studies, based on the following eligibility criteria: reading of the title; reading of abstracts; and reading of the full texts. Eligibility for inclusion in the final studies was verified by calculating the degree of agreement or reproducibility between two data sets using Cohen’s Kappa index (Cohen, 1960). A value greater than 0.87 was obtained, indicating a level of perfect agreement between evaluators (Anguera & Hernández-Mendo, 2014; Landis & Koch, 1977).

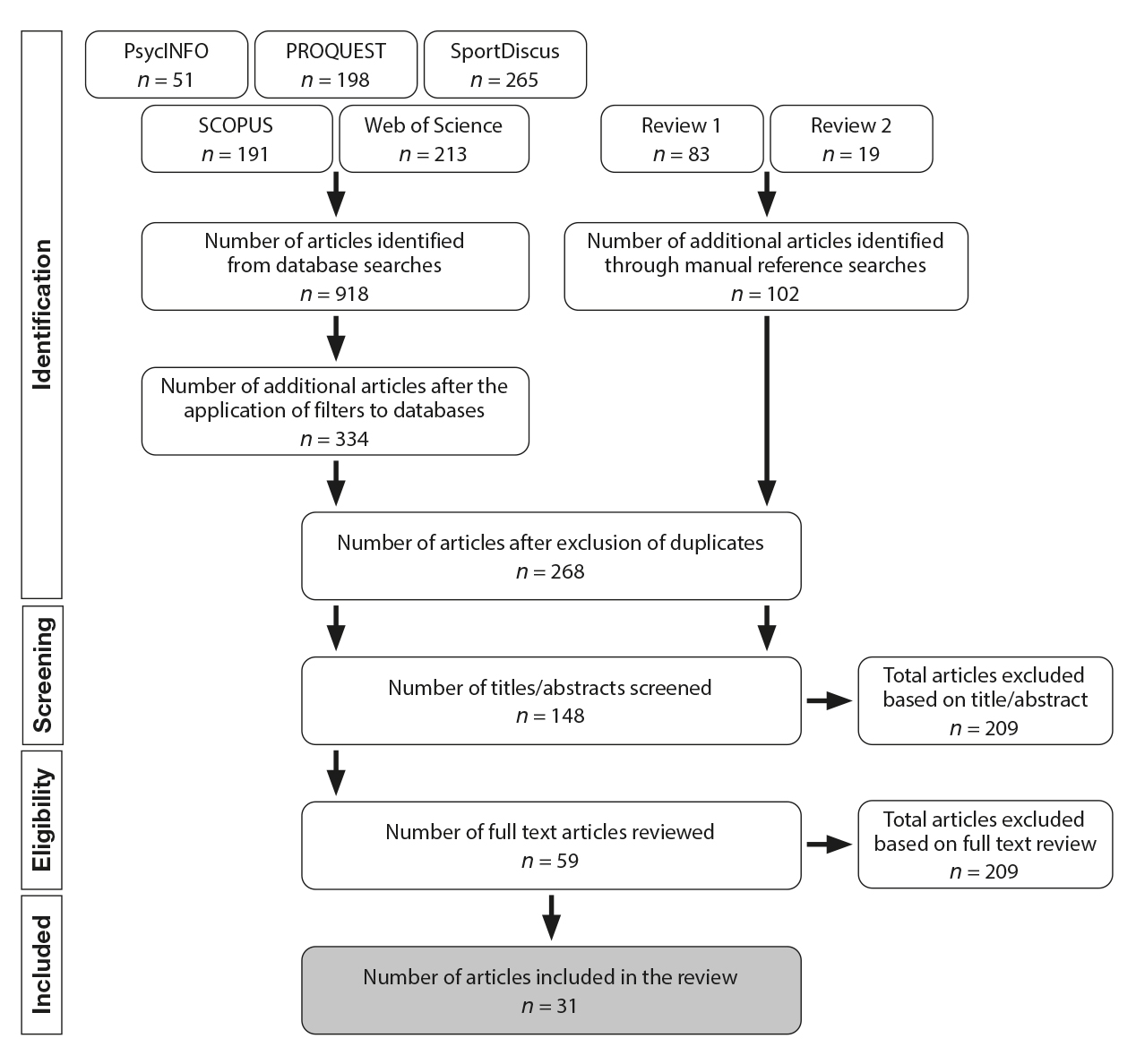

The search in the (primary and secondary) databases was performed in the first fortnight of November 2018 and yielded 1,020 records. 179 articles were excluded in the screening stage through the reading of the titles, because they failed to fulfil the following PECOS criteria: participant (9); exposure (4); outcome (132); study (3); exposure/outcome (8); participant/outcome (19); participant/study (2); outcome/study (2).

Following the reading of the abstracts 30 articles were ruled out on the strength of the following criteria: participant (8); outcome (7); study (4); participant/outcome (6); participant/exposure (5). Finally, in the eligibility stage, 28 articles that did not meet the outcome (27) and language (1) criteria were ruled out. A flow chart summarizing the study selection process is presented in Figure 2.

Evaluation of the methodological quality of the studies

Each one of the studies under review was independently appraised for quality by two researchers using the adapted checklist of the items included in the cross-sectional studies (STROBE – Elm et al., 2008). The checklist was originally comprised of 22 items, 17 of which were used in this study and are related to the title and abstract of the article (item 1), the introduction (items 2 and 3), the methods (items 4-8 and 10-12), the results (items 13-14 and 16) and the discussion sections (items 18-20).

The studies were classified according to the following cutoff points: A (>80% high); B (50% to 80% moderate); and C (<50% low). The cutoff points were obtained from the sum of the score applied to each item: 0 (does not answer); 1 (answers) (Olmos et al., 2008). Disagreements between the investigators were resolved by consensus. The methodological quality scores for all the studies included are presented in Table 1.

Data extraction and analysis

The studies extracted were organized and archived using Endnote (X7) software, while categorization and analysis were performed with the aid of the QSR NVivo PRO software (version 12). According to the information presented in the studies, the characteristics (year, study location, gender, stage of sport development – based on age – kind of sport; social agents investigated; type of research, instrument and software used) and study quality were quantitatively analysed using descriptive statistics (absolute frequency).

Results

The study findings were qualitatively analysed through the creation of analysis categories and subcategories, defined a priori, based on the conceptual framework, and a posteriori, based on the empirical data of the studies: social agents (family members, coaches and teammates); type of social support (emotional, informative, tangible); and level of social support (positive, indifferent, negative).

Characteristics of the studies

The characteristics of the 31 studies selected for this systematic review are presented in Table 1. Most of these research was published as of 2010 (21). In terms of study site, four were conducted in the United States of America and four in the UK.

The bulk of the research was conducted with athletes of both sexes (24), while only one was conducted with male athletes. With regard to the athletes’ long-term development stage (Côté et al., 2003), 10 studies were conducted with athletes in the three stages (diversification, specialization, investment), and 14 studies included individual and team sport athletes.

The studies using a quantitative approach (16) collected data through questionnaires (16), while qualitative approach-based studies (14) employed semi-structured interviews (10), and only one research piece was conducted with both approaches. The SPSS (n = 4) and NVivo (n = 4) software applications were used most to assist in data analysis. There was also a predominance of studies that took into account the athletes’ perception of the support provided by their families (13) (Table 1).

Table 1

Summary of study characteristics.

Risk of bias

Based on the guidelines used (Elm et al., 2008; Olmos et al., 2008), most studies (23) were classified as having a high methodological quality, and eight studies were classified as being moderate-quality. Overall, the risk of bias in the studies included was deemed relatively low.

Social agents, type and level of social support

The study results were organized around the influence of the main social agents investigated (family members, coaches, teammates), focusing on the type (emotional, informative, tangible) and the level of support (positive, indifferent, negative) perceived by the athletes.

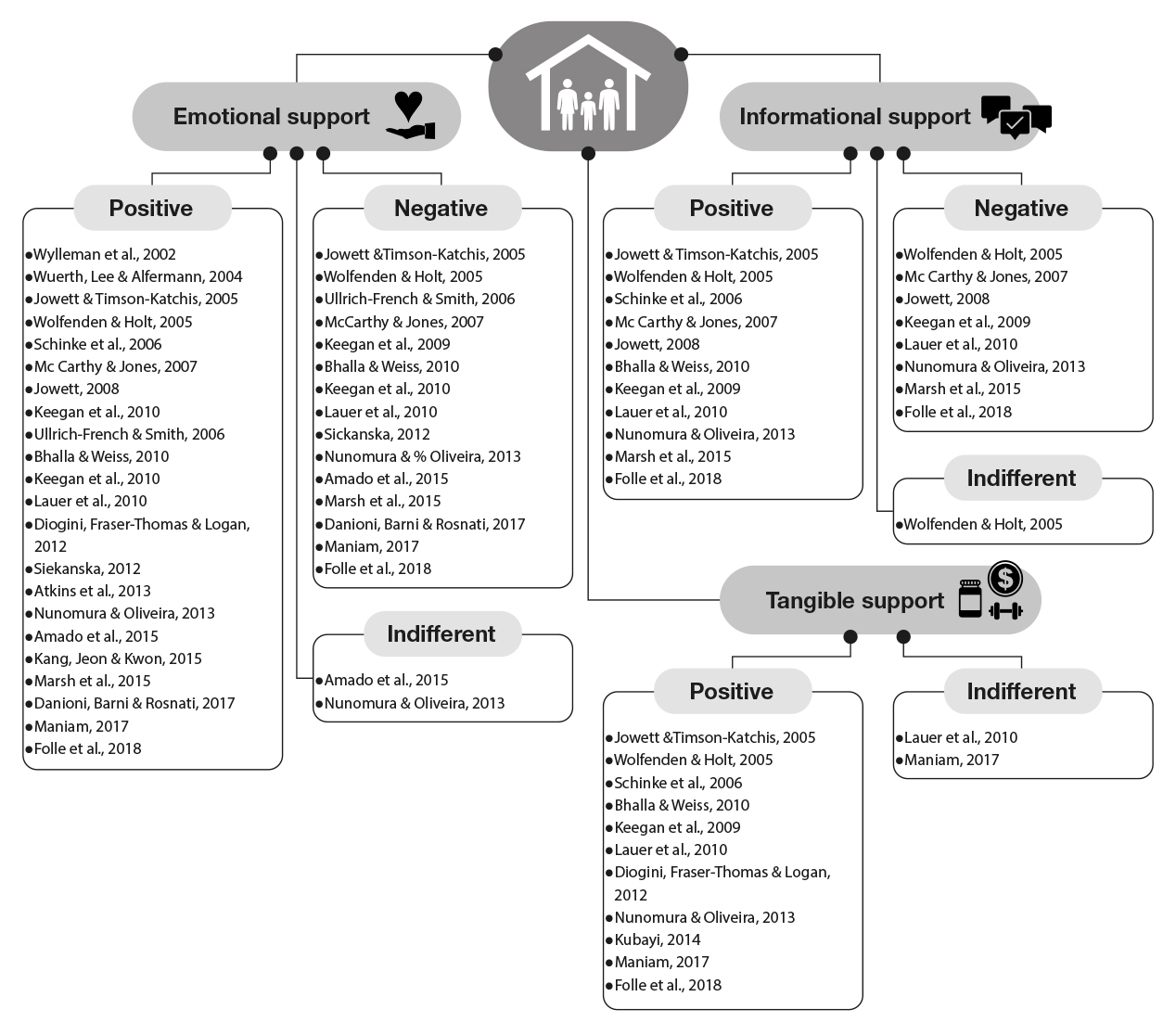

Family support

The information included about the influence of family members was taken from 24 studies (Figure 3). Our analysis showed that according to the perception of the athletes investigated in the studies selected family member support was predominantly emotional.

The studies showed that the emotional support (23) provided by the family members was identified as a key factor in motivating athletes to do sport, showing that in general they were present (at training and competitions), provided encouragement and believed in the benefits of doing sport. However, in some of these studies, emotional support (16) from the family was also negatively rated by some athletes. In these cases, over-involvement (criticism, spontaneous expressions of disappointment, too much emphasis on winning, unrealistic expectations), rather than motivating, became a source of pressure and stress, particularly in competitive situations. In addition, two studies revealed that some athletes were indifferent to the type of emotional support provided by their family.

Our research findings showed that the family seeks to pass on information related to patterns of nutrition, rest, training and game performance through tips, advice and feedback. In general, this support was interpreted positively by the athletes investigated. On the other hand, the same instructional behaviours (7), when supported by deleterious aspects (negative feedback, disproportionate pressure), led the athletes to feel frustrated and demotivated in their involvement in the sport. In addition, one study emphasized that informative support by family members is perceived indifferently by athletes and has no influence on their doing sport (Wolfenden & Holt, 2005).

Positive perceptions of tangible support (11) showed that the availability of the family (the purchase of sports material and logistical support) for training and competitions was acknowledged by the athletes. In turn, disproportionate investment (2) led some athletes to feel pressured and dissatisfied with the support provided by their family.

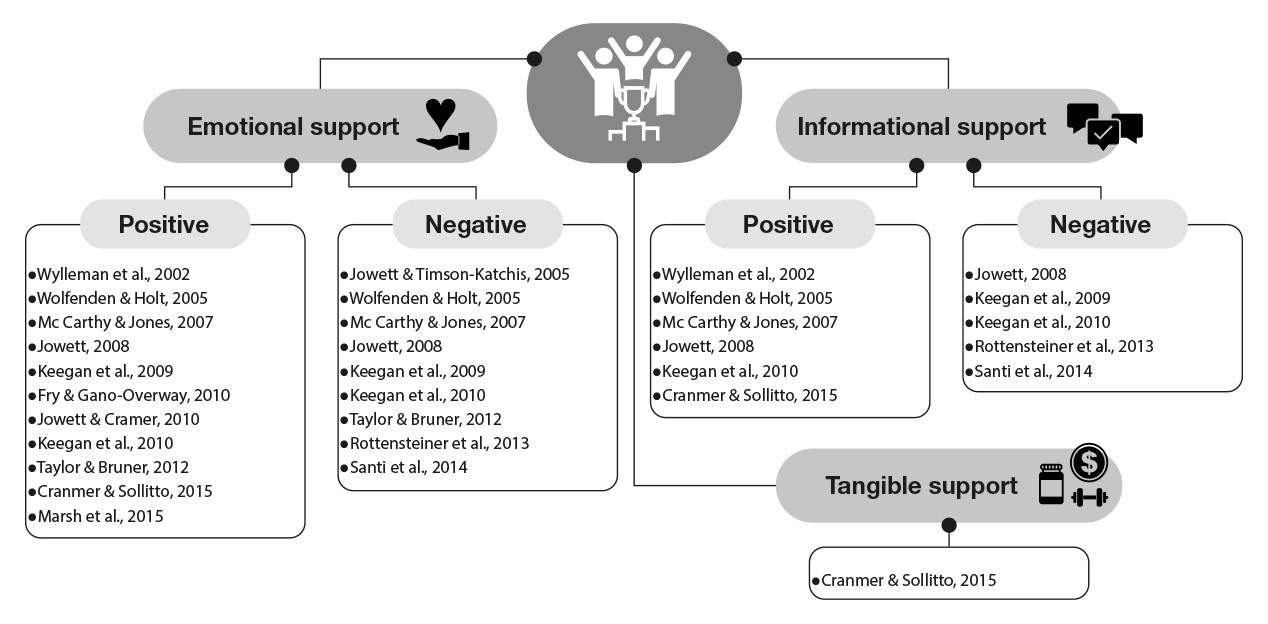

Coach support

The information about the influence of the coaches was taken from the 14 studies shown in Figure 4. We observed, according to the perception of the athletes investigated, that the support provided to them by their coaches was mainly emotional and informative.

The results showed that positive emotional support from the coaches (motivational climate, trust and respect) directly affected the athletes’ commitment to the sport (11). However, negative situations (demands, pressure, focus on results and sports performance) led athletes to feel pressured by the coach and dissatisfied with the sport (9). Perceptions related to informative support (feedback, orientation, tips), particularly for improving athletic performance, were highlighted by athletes as generating effective forms of motivation (5). However, some athletes pointed out that coach feedback was excessively critical and consequently had a negative influence on their confidence and development in their sport (5). Tangible support was poorly expressed in the athletes’ perceptions (1).

Teammate support

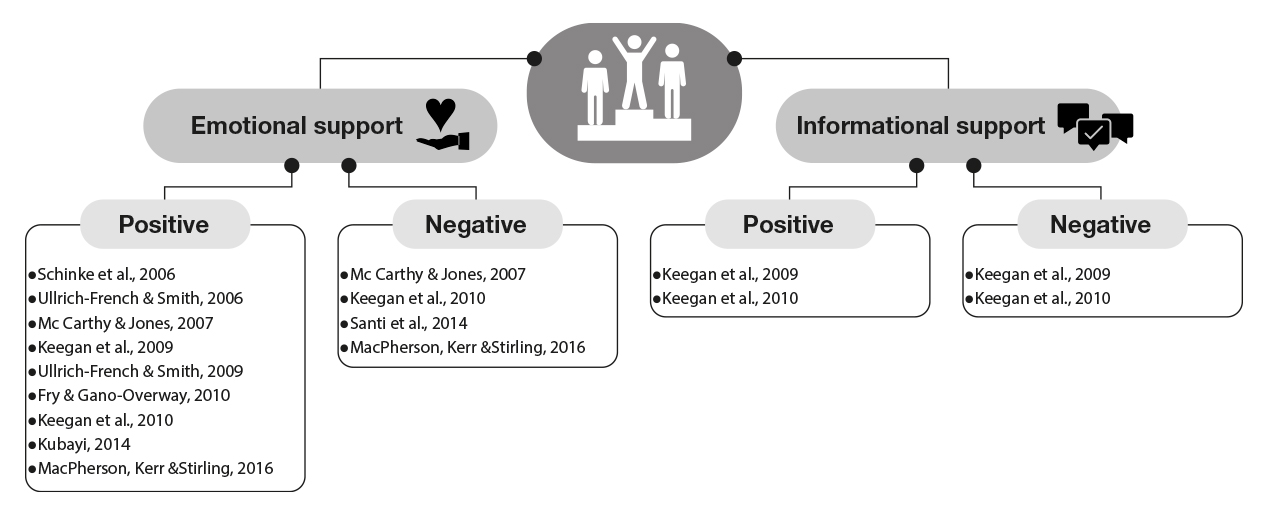

The information analysed regarding the influence of teammates was taken from nine studies (Figure 5). In the athletes’ perception, teammates provided mainly emotional support in the practice of sport.

A positive relationship with teammates (friendship, acceptance, encouragement) has been shown to contribute to the quality of athletes’ experiences with the sport (8). However, negative attitudes (rejection, lack of support, ego) led athletes to develop competitiveness and rivalry with colleagues in their sport (4). Informative support (verbal comments and positive feedback) from colleagues was highlighted by athletes as a motivating factor in several situations (2). However, unfavourable aspects (criticism and negative feedback) emerged in competitiveness between athletes and prompted poorly adaptive sports-related consequences (2).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to analyse the scientific publications on the influence of social agents on sports to identify the types and levels of support provided to athletes by family members, coaches and teammates. Overall, this review pointed to an increase in the number of publications about the topic since 2010, conducted predominantly with athletes in the three stages of the sports practice, of both sexes and focusing on the analysis of social support by family members. The evidence suggests that family members provided the three types of support (emotional, informative and tangible) to athletes, while coaches mainly provided emotional and informative support and teammates emotional support.

The increasing number of publications about social influences on sport brings to light the current importance of the topic and researchers’ concern with understanding the factors that interfere in the development of athletes, from the grass roots through to high-performance. This evidence indicates that research has sought to attain a multidimensional understanding of sport, particularly age- and gender-related variables, which can help practitioners to provide adequate support to athletes in the different stages of development and the development of both sexes (Sheridan et al., 2014).

One of the most relevant elements that emerged from this study was the range of research developed, with a specific focus on the family’s influence on athletes’ development, bridging a gap previously highlighted in the literature (Fredricks & Eccles, 2004). The athletes investigated in the different studies analysed found their main source of support in the family, regardless of their gender and stage in the sport. This means that throughout the athlete’s trajectory, from initiation through to elite sport, and regardless of the type and level of support, family members bring a significant influence to bear upon athletes’ careers, thus evincing the importance of the study of this agent, as has already been emphasised in the literature (Côté, 1999; Fraser-Thomas et al., 2005).

In this review, we hypothesised that family members provided greater emotional and tangible support to athletes. This hypothesis was partially supported, since the three types of support were perceived by the athletes. The evidence found in the selected research suggests that family members can mould athletes’ experiences, which will be favourable if they show that they control emotions, respect, ethics and that they are committed to the athlete’s goals. To this end, the family needs to understand that athletes will not be able to continue their involvement with the sport alone and that being empathic to the challenges they face in this setting will increase their chances of being successful in their career (Knight et al., 2018).

On the other hand, although positive levels of support are perceived by the athletes, a high number of studies have pointed to negative perceptions among athletes in relation to the family. In seeking to maximise benefits, especially for younger athletes, family members often engage in high levels of emotional, informative and tangible support to the detriment of the athletes’ sporting experiences.

The results showed that negative family behaviours such as pressure, demands and overemphasis on victory and performance create unrealistic expectations and dissatisfaction with sports. Another potentially significant element was the allocation of the family’s financial resources to athletes’ sports activities. It transpires that family members who are heavily invested in young athletes’ sports carees expect some kind of return on this investment.

However, this type of situation can lead the athlete to feel over-pressured, detracting from the pleasure of their sport and consequently reducing their commitment to it (Dunn et al., 2016, Latorre-Román et al., 2020). Therefore, even when the support is positive it can also be perceived as negative, depending on how it is perceived and experienced by the the athlete.

The information obtained from this review showed coaches to be complementary sources of support. The second hypothesis proposed was not verified, because even when informative support is provided, emotional support was the support perceived most by athletes in their relationship with the coach. The results of the studies showed emotional and informative support by the coach, mainly through motivation, feedback and counselling, can forge lasting relationships that may lead the athletes to prolong their involvement with the sport (Pérez-González et al., 2019).

In turn, the coach can also be a negative source of support, when the latter is accompanied by disproportionate pressure and negative feedback on athletes’ performance, prompting a lack of balance and of affective bonds that would otherwise be conducive to a relationship grounded in mutual respect and trust. Coaches must understand their athletes, inside and outside the context of sport and be seen to take a real interest in their lives. This attitude can help them to address athletes’ needs better and help them to develop realistic skills and pursue goals that may lead to a successful sports career (Nascimento Junior et al., 2020; Rottensteiner et al., 2013).

Tangible support from coaches was rarely perceived by athletes in the studies analysed. This type of support includes the recognition that the coach provides the athlete with benefits or services (rehabilitation, injury treatment, training and exercise schedules, sports equipment or financial aid) intended to assist the athlete in the sport (Holt & Dunn, 2004; Rees & Hardy, 2000). Perhaps, particularly in younger athletes, this kind of support is not perceived as coming directly from the coach and may give family members or even the club or sports centre such responsibilities, which may have reduced the recognition of these acts in the analysis of the support provided by the coaches.

The relationship with teammates has been shown to contribute to the quality of athletes’ experiences, mainly through emotional support, according to the third hypothesis of this study. Although the sports literature has focused predominantly on how adult social agents, such as family members and coaches, can shape athletes’ development (Marsh et al., 2015), there seems to be a growing recognition that interaction with teammates constitutes a source for generating positive results in sport (Macpherson et al., 2016).

The results of the studies suggest that quality of friendship and peer acceptance are closely related to motivation, companionship, and consequently to a greater commitment to the sport on the part of the athlete (Ullrich- French & Smith, 2006).

As sports practice advances, the role of teammates is being reformulated and assumes more and more importance, especially in the specialization and investment phases. Becasuse in these stages, perhaps the most complex for athletes, there is a transition from adolescence and a habitual shift in roles played by significant adults (Côté et al., 2016).

However, conflicts with teammates can lead athletes to give up the sport completely (Scott et al., 2019). The evidence obtained, albeit predominantly positive, is consistent with that of Sheridan et al. (2014) in indicating that negative emotional and informative support from teammates involving an ego climate, high competitiveness and pejorative feedback is strongly related to burnout in sports. This means that athletes’ continuity in the sport will also depend on the quality of their relationship with their teammates, which will be fundamental in the taking of such a decision.

Comparing the evidence in this review to the existing literature, the athlete’s sports experience is directly influenced by the type and level of support from social agents in the form of different values and beliefs (Defreese & Smith, 2014). In this research, the results of the studies analysed showed that the support of social agents is predominantly perceived as positive, in accordance with the fourth hypothesis of this study. Thus, even when negative support is provided, it is perceived less often than positive support, showing that family members, coaches and teammates fulfilled their role of sharing athletes’ needs, providing emotional, informative and tangible support to assist them in sports activities.

From this perspective, in order to help athletes to develop and effectively protect them from undesirable situations, it would seem crucial to look more closely at how social agents influence athletes’ development in sport. This requires not only the analysis of the available research information, but also the construction of new studies that achieve a better understanding of the psychological mechanisms in specific contexts of sports culture and provide a greater understanding of how certain types and levels of support can influence continuation or abandonment of a career in sport.

Conclusions

The results of this systematic review provided a clear indication of the breadth and complexity of the different types and levels of support provided to athletes by social agents. Family members were identified as the only providers of all three types of support, giving athletes emotional, informative and tangible support at all three levels (positive, indifferent, and negative). Coaches provided greater emotional and informative support, whereas teammates demonstrated greater emotional support, both positive and negative, according to the athletes’ perception. Overall, it would appear that identifying specific roles and responsibilities to be provided by each social agent, as well as a knowledge of athletes’ demands and sports goals, would be helpful in guiding the development of a successful athletic career.

Several practical proposals for family members, coaches and the other social agents involved in the context of sport who work with athletes emerged from this review. Family members, coaches and teammates have been shown to bring a positive influence to bear on several factors that affect the development of athletes in sport. Family members were the only providers of all three types of support, thus indicating the significant and ubiquitous role of the family, both positively and negatively. This discovery can help family members to revisit their attitudes and the types of support they provide to athletes to ensure that supportive relationships are favourable and positive. This information can go some way to understand what specific types of support can help to protect athletes from the harmful effects of specific types of stressful effects arising from their involvement in sport over time. Therefore, in order to help athletes to maintain their involvement in sport, the closest social agents need to be aware of the type and level of support they provide to athletes at different times in their career as athletes.

Limitations and future directions

This study makes important contributions on how athletes perceive the influences of social agents in sport, analysing the types and levels of support provided by family members, coaches and teammates. However, this study has several methodological limitations, to wit: the inclusion of studies published only in English (this may have influenced the characteristics of the sample and may have led reports that could be culturally significant to be omitted); the elimination of studies that did not meet some of the eligibility criteria (out-of-date studies – 2001-2018) and did not observe the athlete’s perception as the focal point of the research, concentrating rather on the perception of parents, coaches and colleagues of their influence on athletes’ activity; failing to consider other social agents (teachers, non-sports friends, businessmen, sports members), who may also have limited the outcomes of the review. In addition, the sample sizes and the competition levels of the investigated participants were not considered and nor were comparisons drawn between athletes based on age, gender, sport and country of origin, which might go some way to explaining the results, based on the characteristics of the samples. Future studies could use a cross section of their research to understand how an athlete’s social support network can influence them before, during and after a sport season, which would allow researchers to examine the influences of social agent relationships over time. Including athletic populations from different cultures could help to test the generality and validity of existing knowledge. Moreover, including insights from multiple social relationships and exploring possible moderating effects in a research project may yield meaningful information and make valuable contributions to the existing literature.

Funding

This study was partly financed by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) – Brasil – Finance Code 001.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

[1] Amado, D., Sánchez-Oliva, D., González-Ponce, I., Pulido-González J. J. & Sánchez-Miguel, P. A. (2015). Incidence of Parental Support and Pressure on Their Children’s Motivational Processes towards Sport Practice Regarding Gender. PlosOne, 10, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128015

[2] Anguera, M. T. & Hernández-Mendo, A. (2014). Metodología observacional y psicología del deporte: Estado de la cuestión. Revista de Psicología del Deporte. 23(1), 103-109.

[3] Atkins, M. R., Johnson, D. M., Force, E. C. & Petrie, T. A. (2013). “Do I Still Want to Play?” Parents’ and Peers’ Influences on Girls’ Continuation in Sport. Journal of Sport Behavior, 36(4), 329-345.

[4] Bhalla, J. A. & Weiss, M. R. (2010). A Cross-Cultural Perspective of Parental Influence on Female Adolescents’ Achievement Beliefs and Behaviors in Sport and School Domains. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 81(), 494-505. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2010.10599711

[5] Bremer, L. K. (2012). Parental Involvement, Pressure, and Support in Youth Sport: A Narrative Literature Review. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 4(1), 235-248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2012.00129.x

[6] Camerino, O., Valero-Valenzuela, A., Prat, Q., Manzano Sánchez, D. & Castañer, M. (2019). Optimizing Education: A Mixed Methods Approach Oriented to Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR). Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01439

[7] Côté, J. (1999). The influence of the family in the development of talent in sport. The Sport Psychologist, 13, 395-417. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.13.4.395

[8] Côté, J., Baker, J. & Abernethy, B. (2003). From play to practice: a developmental framework for the acquisition of expertise in team sport. En: Starkes, J.; Ericsson, K. A. (Eds.), Expert performance in sports: Advances in research on sport expertise (pp. 89-113). Champaign: Human Kinetics.

[9] Côté, J., Turnnidge, J. & Vierimaa, M. (2016). A personal Assets Approach to Youth Sport. En.: Green, K.; Smith, A. Routledge Hanbook of Youth Sport (pp. 243-255). London, New York: Routledge.

[10] Coutinho, P., Mesquita, I. & Fonseca, A. M. (2018). Influência parental na participação desportiva do atleta: uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 27(2), 47-58.

[11] Cutrona, C. E. & Russel, D. W. (1990). Type of social support and specific stress: Towards a theory of optimal matching. En B. R. Sarason, I. G. Sarason, & G. R. Pierce (Eds.). Social support: An interactional view (pp. 319-366). New York, NY: Wiley.

[12] Cranmer, G. A., & Sollitto, M. (2015). Sport Support: Received Social Support as a Predictor of Athlete Satisfaction. Communication Research Reports, 32, 253-264. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2015.1052900

[13] Danioni, F., Barni, D., & Rosnati, R. (2017). Transmitting sport values: The importance of parental involvement in Children’s Sport Activity. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 13(1), 75-92. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v13i1.1265

[14] DeFreese, J. D. & Smith, A. L. (2014). Athlete social support, negative social interactions, and psychological health across a competitive sport season. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 36(6), 619-630. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2014-0040

[15] Dionigi, R. A., Fraser-Thomas, J., & Logan, J. (2012). The nature of family influences on sport participation in Masters athletes. Annals of Leisure Research, 15(4), 366-388. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2012.744274

[16] Dunn, R. C., Dorsch, T. E., King, M. Q. & Rothlisberger, K. J. (2016). The impact of family financial investment on perceived parent pressure and child enjoyment and commitment in organized youth sport. Family Relations, 65(1), 287-299. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12193

[17] Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocok, S. J., Gotzsche, P. C. & Vandenbrouche, J. P. (2008). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(3), 344-349. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD

[18] Folle, A., Nascimento, J. V., Salles, W. N., Maciel, L. F. P. & Dallegrave, E. J. (2018). Family involvement in the process of women’s basketball sports development. Journal of Physical Education, 29(e2914), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.4025/jphyseduc.v29i1.2914

[19] Fraser-Thomas, J. L., Côté, J., & Deakin, J. (2005). Youth sport programs: an avenue to foster positive youth development. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 10(1), 19-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/1740898042000334890

[20] Fraser-Thomas, J. & Côté, J. (2009). Understanding Adolescents’ Positive and Negative Developmental Experiences in Sport. The Sport Psychologist, 23(1), 3-23. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.23.1.3

[21] Fraser-Thomas, J., Côté, J. & Deakin, J. (2008a). Understanding dropout and prolonged engagement in adolescent competitive sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 9(5), 645-662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2007.08.003

[22] Fredricks, J. A. & Eccles, J. S. (2004). Parental influences on youth involvement in sports. En M. R. Weiss (Ed.), Developmental sport and exercise psychology: A lifespan perspective (pp. 145-164). Morgantown, WV, US: Fitness Information Technology.

[23] Fry, M. D., & Lori A. G. (2010). Exploring the Contribution of the Caring Climate to the Youth Sport Experience. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 22(3), 294-304. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413201003776352

[24] Goldsmith, D. J. (2004). Communicating social support. Cambridge, England: Cambridge Press.

[25] Holt, N. L. & Dunn, J. G. H. (2004). Toward a grounded theory of the psychosocial competencies and environmental conditions associated with soccer success. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 16(3), 199-219. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200490437949

[26] Holt, N. L. & Sehn, Z. L. (2008). Processes associated with positive youth development and participation in competitive youth sport. In: N. L. Holt (Ed.), Positive youth development through sport: international studies in physical education and youth sport (pp. 119-137). London: British Library.

[27] Jowett, S. (2008). Outgrowing the familial coach - athlete relationship. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 39(1), 20-40.

[28] Jowett, S. & Cockerill, I. M. (2003). Olympic medalists’ perspective of the athlete-coach relationship. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 4(6), 313-331. https://doi.org/10.5007/1980-0037.2015v17n6p650

[29] Jowett, S., & Cramer, D. (2010). The prediction of young athletes’ physical self from perceptions of relationships with parents and coaches. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(2), 140-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.10.001

[30] Jowett, S., & Timson-Katchis, M. (2005). Social Networks in Sport: Parental Influence on the Coach-Athlete Relationship. The Sport Psychologist, 19(3), 267-287. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.19.3.267

[31] Kang, S. Jeon, H., & Kwon, S. (2015). Parental attachment as a mediator between parental social support and self-esteem as perceived by Korean sports middle and high school athletes. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 120(1), 288-303. https://doi.org/10.2466/10.PMS.120v11x6

[32] Kassing, J. W., Billings, A. C., Brown, R. S., Halone, K. K., Harrison, K., Krizek, R. L, Meân, L. J. & Turman, P. D. (2004). Communication in the community of sport: The process of enacting, (re)producing, consuming, and organizing sport. En P. J. Kalbfleisch (Ed.). Communication yearbook, 28 (pp.373-409). New York, NY: Routledge.

[33] Keegan, R. J., Spay, C. M., Harwood, C. G. & Lavallee, D. E. (2010). The Motivational Atmosphere in Youth Sport: Coach, Parent, and Peer Influences on Motivation in Specializing Sport Participants. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 22(1), 87-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200903421267

[34] Keegan, R. J., Harwood, C. G., Spray, C. M., & Lavallee, D. E. (2009). A qualitative investigation exploring the motivational climate in early career sports participants: Coach, parent and peer influences on sport motivation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10(3), 361-372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2008.12.003

[35] Knight, C. J., Harwood, C. G. & Sellars, P. (2018). Supporting adolescent athletes’ dual careers: The role of an athlete’s social support network. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 38, 137-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.06.007

[36] Kubayi, N. A., Jooste, J., Toriola, A. L. & Paul, Y. (2014). Familial and peer influences on sport participation among adolescents in rural South African secondary schools. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(20), 1305-1308. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n20p1305

[37] Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorial data. Biometrics, 33(4), 159-174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310

[38] Latorre-Román, P. Á., Bueno-Cruz, M. T., Martínez-Redondo, M. & Salas-Sánchez, J. (2020). Prosocial and Antisocial Behaviour in School Sports. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 139, 10-18. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2020/1).139.02

[39] Lauer, L. G., Gould, D., Roman, N., & Pierce, M. (2010). Parental behaviors that affect junior tennis player development. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(6), 487-496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.06.008

[40] McCarthy, P. J. & Jones, M. V. (2007). A qualitative study of sport enjoyment in the sampling years. Sport Psychologist, 21(4), 400 - 416. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.21.4.400

[41] MacPherson, E., Kerr, G. & Stirling, A. (2016). The influence of peer groups in organized sport on female adolescents’ identity development. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 23, 73-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.10.002

[42] Maniam, V. (2017). Secondary school students’ participation in sports and their parents’ level of support: A qualitative study. Physical Culture and Sport, Studies and Research, 76(1), 14-22. https://doi.org/10.1515/pcssr-2017-0025

[43] Marsh, A., Zavilla, S., Acuna, K. & Poczwardowski, A. (2015). Perception of purpose and parental involvement in competitive youth sport. Health Psychology Report, 3(3), 13-23. https://doi.org/10.5114/hpr.2015.48897

[44] Meline, T. (2006). Selecting Studies for Systematic Review: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria. Contemporary issues in communication science and disorders, 33(1), 21-27. https://doi.org/10.1044/cicsd_33_S_21

[45] Moher, D., Liberati, A., Telzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. (2015). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde, 24(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

[46] Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P. & Stewart, L. A. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

[47] Mora, A., Sousa, C. & Cruz, J. (2014). The Motivational Climate, Self-Esteem and Anxiety in Young Players in a Basketball Club. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 117, 43-50. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2014/3).117.04

[48] Nascimento Junior, J.R., Silva, E.C., Freire, G.L.M., Granja, C.T.L., Silva, A.A. & Oliveira, D.V. (2020). Athlete’s motivation and the quality of his relationship with the coach. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 142, 21-28. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2020/4).142.03

[49] Nunomura, M. & Oliveira, M. S. (2013). Parents’ support in the sports career of young gymnasts. Science of Gymnastics Journal, 5(1), 5-18.

[50] Olmos, M., Antelo, M., Vazquez, H., Smecuol, E., Mauriño, E. & Bai, J. C. (2008). Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies on the prevalence of fractures in coeliac disease. Digestive and Liver Disease, 40(1), 46-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2007.09.006

[51] Prat, Q., Camerino, O., Castañer, M., Andueza, J. & Puigarnau, S. (2019). The Personal and Social Responsibility Model to Enhance Innovation in Physical Education. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 136, 83-99. https://dx.doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2019/2).136.06

[52] Pérez-González, A. M., Valero-Valenzuela, A., Moreno-Murcia, J. A. & Sánchez-Alcaraz, B. J. (2019). Systematic Review of Autonomy Support in Physical Education. Apunts Educación Física y Deporte, 138(4), 51-61. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2019/4).138.04

[53] Puigarnau, S., Camerino, O., Castañer, M., Prat, Q. & Anguera, M.T. (2016). El apoyo a la autonomía en practicantes de centros deportivos y de fitness para aumentar su motivación. RICYDE-Revista Internacional de Ciencias del Deporte, 43(12), 48-64. https://doi.org/10.5232/ricyde2016.04303

[54] Rees, T. & Hardy, L. (2000). An investigation of the social support experiences of high-level sport performers. The Sport Psychologist, 14(4), 327-347. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.14.4.327

[55] Riera, J., Caracuel, J. C., Palmi, J. & Daza, G. (2017). Psychology and Sport: The athlete’s self-skills. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 127, 82-93. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2017/1).127.09

[56] Rottensteiner, C., Laakso, L., Pihlaja, T. & Konttinen, N. (2013). Personal reasons for withdrawal from team sports and the influence of significant others among youth athletes. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 8(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.8.1.19

[57] Santi, G. B., Bruton, U., Peitrantoni, G., & Mellalieu, S. (2014). Sport commitment and participation in masters swimmers: The influence of coach and teammates. European Journal of Sport Science, 14(8), 852-860. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2014.915990

[58] Sanz-Martín, D. (2020). Relationship between Physical Activity in Children and Perceived Support: A Case Studies. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 139, 19-26. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2020/1).139.03

[59] Scott, C. L., Haycraft, E. & Plateau, C. R. (2019). Teammate influences on the eating attitudes and behaviours of athletes: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 43, 183-194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.02.006

[60] Siekańska, M. (2012). Athletes’ Perception of Parental Support and Its Influence in Sports Accomplishments - A Retrospective Study. Human Movement, 13(1), 380-387. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10038-012-0046-x

[61] Schinke, R. J., Eyes, M., Danielson, R., Michel, G., Peltier, D., Pheasant, C., Enosse, L., & Peltier, M. (2006). Cultural social support for Canadian aboriginal elite athletes during their sport development. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 37(2), 330-348. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2007.9671815

[62] Sheridan, D., Coffee, P. & Lavallee, D. (2014). A systematic review of social support in youth sport. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7(1), 198-228. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2014.931999

[63] Ullrich-French, S. & Smith, A. L. (2006). Perceptions of relationships with parents and peers in youth sport: Independent and combined prediction of motivational outcomes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 7(2), 193- 214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2005.08.006

[64] Valero-Valenzuela, A., Camerino, O., Manzano-Sánchez, D., Prat, Q. & Castañer, M. (2020). Enhancing Learner Motivation and Classroom Social Climate: A Mixed Methods Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 5272. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155272

[65] Wolfenden, L. E. & Holt, N. L. (2005). Talent development in elite junior tennis: Perceptions of players, parents, and coaches. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 17(2), 108-126. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200590932416

[66] Wuerth, S., Lee, M. J., & Alfermann, D. (2004). Parental involvement and athletes’ career in youth sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 5(1), 21-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(02)00047-X

[67] Wylleman, P. & Lavallee, D. (2004). A developmental perspective on transitions faced by athletes. En M. Weiss (Ed.). Developmental sport and exercise psychology: A lifespan perspective (pp. 507-527). Morgantown, WV: FIT.

ISSN: 2014-0983

Received: January 06, 2021

Accepted: March 18, 2021

Published: July 01, 2021

Editor: © Generalitat de Catalunya Departament de la Presidència Institut Nacional d’Educació Física de Catalunya (INEFC)

© Copyright Generalitat de Catalunya (INEFC). This article is available from url https://www.revista-apunts.com/. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en